Sprucing Up the Pine Box: Inside Ghana’s Novelty Coffin Industry

The Kane Kwei Coffins workshop in Teshie, Accra has been creating and selling fantasy coffins since the 1980s (All photos: Angelica Calabrese)

The Kane Kwei Coffins workshop in Teshie, Accra has been creating and selling fantasy coffins since the 1980s (All photos: Angelica Calabrese)

The workshop of one of the most well-known fantasy coffin carvers in the world is squeezed between a barbershop and a clothing store, in the shadow of a three-story Melcom supermarket. In front of the workshop, children skitter through the dirt and women sell fried yam, cell phone credit, and balls of fermented corn mash called kenkey. A generator’s incessant hum fills the air, alongside the echoing calls of the passing tro-tros and the ubiquitous tune of high-life music. Above the shop, a faded wooden fish hangs above a plank with “KANE KWEI COFFINS” painted in black block letters. Inside, Eric Adjetey Anang and his carpenters are spearheading the creation of Ghana’s most fascinating and internationally renowned artistic product: abebuu adekai, or fantasy coffins.

Abebuu adekai, meaning “proverbial coffins” in the language of the Ga ethnic group, are coffins that tell a story. They are designed to represent the life of the deceased person, often referencing his or her work, dreams, and even vices. Perhaps a writer might want to be accompanied to the afterworld in a coffin-sized replica of her favorite pen; a hairdresser, inside her trusty blow dryer. An bartender might instead choose a bottle of his favorite whiskey. If you can dream it, Eric Adjetey Anang and his apprentices can craft it. And if they can’t, one of the many other workshops in the surrounding area surely can.

On a sticky Friday afternoon, I braved the Accra traffic to venture to Teshie to visit Eric Adjetey Anang at the Kane Kwei Coffins workshop. Sitting between an eight-foot long green lobster, a human-sized guitar, and a towering bottle of Paradise talc powder, Anang took a break from coffin construction to chat with me about the past, present, and future of his coffin-carving craft.

Eric Adjetey-Anang and a Paradise bottle coffin. This bottle was designed as an art piece, rather than for burial.

Eric Adjetey-Anang and a Paradise bottle coffin. This bottle was designed as an art piece, rather than for burial.

In Ghana, funerals have always been an occasion for both mourning and celebration. In many of the traditional religions, people believed that dead ancestors could powerfully impact the lives of the living, and elaborate funeral ceremonies and celebrations ensured the goodwill of the recently passed. Chiefs and religious leaders merited additional consideration: scholars say that occasionally, chiefs were buried in the carved wooden palanquins upon which they had been carried during their reign.

Fantasy coffins gained popularity among the Ga people of the Greater Accra region through the craftsmanship of Anang’s grandfather, Seth Kane Kwei, in the mid-twentieth century. The coffins were traditionally envisioned to represent the lives and livelihoods of those whom they carried to the grave — for example, a fish for a fisherman and a hammer for a carpenter.

According to Anang, Seth Kane Kwei’s first coffin innovation was born from this tradition. Sometime in the 1940s, Kane Kwei convinced the family of a recently deceased chief to bury the chief in his palanquin rather than rushing to craft a standard wooden coffin in the few days before the body began to decay. The carved palanquin would have otherwise just rotted above ground, he argued; why not send it below with its revered owner?

Some years later, in the mid-1950s, Kane Kwei’s grandmother passed away. Accra’s Kotoka International Airport had recently been built a few miles away, and the old lady had loved watching the planes arrive and depart over their Teshie fishing community. In homage to her dream of one day flying in an airplane, Kane Kwei built her an airplane-shaped coffin that would fly her comfortably into the next life.

This was the first time that a carved coffin had been crafted for someone other than a chief or community leader. But as more people learned of his creations, interest grew. The Ga fishermen of the surrounding area began to commission their own fantasy coffins, in the shape of colorful fish or traditional boats. Kane Kwei’s entrepreneurial spirit helped grow the business, and in 1980, he opened the shop that his grandson still runs today.

A lobster coffin in the process of being painted.

By 1992, when Kane Kwei passed away, his Ghanaian fantasy coffins had achieved international acclaim. They had been featured at Magiciens de la Terre, a contemporary art exhibition at the Centre Pompidou in Paris in 1989, and subsequently gained a circle of committed collectors. In the years following his death, his sons Cedi and Soa, notable apprentices like Paa Joe, and his grandson Eric Adjetey Anang, have carried on the tradition.

As Anang tells me of the fish he recently constructed with a mouth full of trash and of an ear of corn whose auction price of $3,000 will fund the construction of a dam in Ghana’s Upper West region, it is clear that he has inherited his grandfather’s spirit of innovation and entrepreneurship. “I’m trying to work on things that have something to say about the community,” he tells me. He and his fellow artisans are transforming the craft first practiced in his grandfather’s small community into an ever more globalized art form.

As a young man, Anang chose to pursue coffin carpentry rather than university studies, having recognized the form’s potential and appeal early on, when collectors and journalists would show up at his grandfather’s workshop, eager to learn more. Today, Anang recounts his upcoming travel plans to the United States and Denmark, and past trips to Senegal and Siberia. He says that today, coffins from the Kane Kwei workshop are on display in the Seattle Art Museum, San Francisco’s deYoung Museum, the National Museum of Funeral History in Houston, the Museum of Death in St. Petersburg, Russia, along with many private galleries.

There are even a few individuals who’ve gotten so excited about Anang’s work that they’ve commissioned their own designer coffins. A few years ago, a man from Delaware requested a coffin in the shape of a Leinenkugel Beer bottle, and shipped one of his old bottles all the way to Accra to ensure that the design was accurate. More recently, an aquarium owner in Florida requested a seahorse.

But these coffins, designed for export and exhibition and made with hard woods and strong glues to weather temperature and time, differ vastly from the intentionally transient pieces crafted for traditional use in Ghana. Of the roughly 300 coffins that the workshop produces per year, only about 20% are for export; the remaining 80% are used for traditional funeral ceremonies in Ghana.

A stool coffin for a chief, and a sneaker-shaped coffin for an avid footballer.

At the workshop, Anang shows me the coffins his current apprentices are working on. Lean, young, and dressed in colorful secondhand clothes plastered with nonsensical phrases, they chatter in Ga as they plane and sand the soft sugar pine. Sawdust thickens the air as we wander towards the pieces currently under construction, all for burial in Ghana: a football sneaker and two stool-shaped coffins that represent the power and authority of a chief. While the exported coffins cost between $1500 and $3000, these coffins cost around 2000 Ghana cedi ($500).

This is a steep price for the average Ghanaian. Not every family is willing to pay so much, though many find creative ways to foot the bill – after all, it’s just one among a suite of funeral expenses that can cost families anywhere from $3,000 to $20,000. Politicians and religious leaders have critiqued the immense amount of money that goes into funeral celebrations, but families continue to spend, often delaying the funeral for up to two months in order to raise the money to cover all of the expenses — not only paying for the body’s spot in the mortuary, but also for posters, chairs and tents, speakers, food, musical groups, and the fantasy coffin itself.

Coffins featured in the Kane Kwei workshop

The months spent fundraising and planning for the funeral give carpenters the chance to create their coffins; in fact, it might even be said that electricity and refrigeration have allowed the craft to flourish. A cocoa pod design, one of the most popular, can take as short as a week to build, whereas a more challenging and innovative request may take up to a few months.

However, even if the coffin is ready, sometimes the family is not, for reasons related to finances, politics, or other issues. “Sometimes the body is kept in the morgue for a year, or two, or more. This coffin has been here for two years,“ Anang says, pointing over my shoulder to a dusty, half-complete, stool-shaped coffin sitting in the workshop area, “and the body is still in the mortuary.”

The thriving funeral industry in Ghana makes coffin-carving an attractive job for many young men who might otherwise pursue farming, fishing, or traditional carpentry. Faced with slim prospects in their home villages, many come to Accra seeking a better future – and those with artistic skills, intelligence, and entrepreneurial spirit can have great success.

Kpakpa Adotey, who runs Eric Carpentry Shop in Labadi, was one of these young men. He came to Accra with only a primary school education and began an apprenticeship with Paa Joe, one of Seth Kane Kwei’s first apprentices. Adotey has now opened up his own shop, where he draws inspiration from the traditional coffin concepts to craft everything from funeral urns to jewelry boxes for sale at local tourist markets. Adotey’s shop is one of about four workshops specialized in the production of fantasy coffins in the Greater Accra region, and all of the carpenters speak with pride about the work that they do and the opportunities it has offered them.

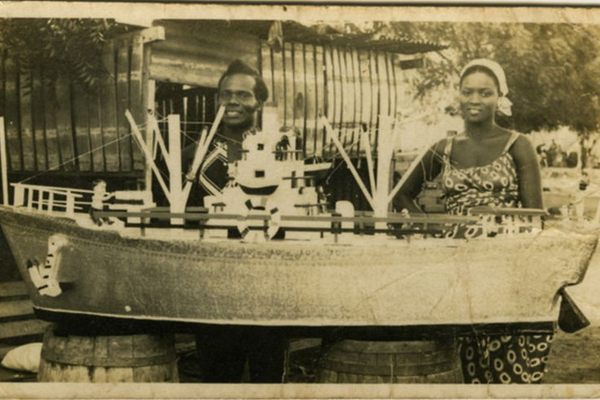

Adotey with a bottle of Star beer and a Kalyppo juice box. Both are intended to be used as cabinets.

“I’m proud of what I’m doing now, because I know a lot of people who are professors, doctors, but they haven’t met the Chancellor of Germany,” Adotey tells me, eyes sparkling. Last year, his workshop was destroyed by a storm, so we sit and chat in broken plastic chairs under a makeshift tarp where he completes his current commissions. “She came here,” he says of Angela Merkel, waving his arm to indicate the gray and sun-bleached courtyard, his neighbor’s laundry drying in the hot breeze. “I had a thirty minute chat with her, I shook her hand,” he says.

Daniel Mensah, of Hello Design Coffins in Teshie, has a similar perspective. “If you see some of my friends, now they don’t have a job to do. But this job is a great job,” he tells me,. Inside his breezy but rickety second-story showroom just down the street from the Kane Kwei shop, there are coffins shaped like lions, eagles, ice cream tubs, blow-dryers, pineapples, bottles of Coca-Cola and beer, and even a Canon camera.

A lion, eagle, and blow-dryer coffin in Mensah’s second-story showroom. Only chiefs can be buried in lion and eagle coffins.

While many of the household goods, furniture, and electronics sold in Ghanaian shops are imported from elsewhere, the fantasy coffins remain the unique domain of skilled artists. Sitting shirtless in his courtyard workshop, with his children running through his feet, Mensah supervises his two apprentices as they use their fingertips to carefully spread filler into the cracks between the wood of a coffin shaped like the pestles used to pound Ghana’s most famous dish, fufu. “Not all carpenters can do this work. It’s great, it’s famous, it’s happy for me,” he says.

These fascinating pieces that merge traditional craft and contemporary art offer a glimpse into regional history and culture, into the fantasies of Ghanaians, and all the fans who have sought out abebuu adekai, coffins that tell a story, from near and far.

On Obscura Day, May 30, join us for an open house at the Kane Kwei Coffin Workshop in Accra, Ghana.

A young apprentice at work in the Kane Kwei carpentry workshop.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook