In Fast-Changing Seattle, an Effort Not to Forget the Past

A new project gathers the collective memory of places that no longer exist.

If anyone has been paying close attention to San Francisco’s growing housing affordability crisis over the past few years, it’s Seattle residents. The parallels between the two cities are hard to miss: Both are experiencing tech-fueled economic booms, and both grapple with physical limitations to growth thanks to their unique geographies along the Pacific coast. The rent in Belltown may not yet be quite as damn high as in Nob Hill, but it certainly seems to be on its way.

Amid reasonable fears about gentrification and genuine excitement over the influx of good-paying jobs, another topic has dominated the discourse in Seattle of late—a near-constant accounting of the various local businesses and gathering spots that are rapidly being replaced by rent pressures or new construction.

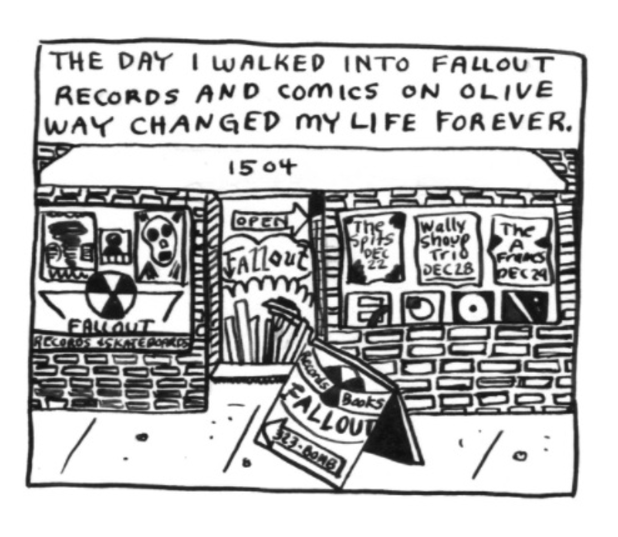

“A little more than two years ago, it felt like every conversation I had seemed to be about places that were disappearing,” says Jaimee Garbacik, editor of Ghosts of Seattle Past, a new anthology of essays, interviews, photography, and graphic art dedicated to places in Seattle that no longer exist. “Every time I went on Facebook, every time I ran into friends, it was, ‘Oh my god, did you hear that this place closed?’”

The book is actually the culmination of years of effort. Ghosts got its start as a small art exhibit, evolved into a crowdsourced mapping project, and eventually became a much larger exhibit with related events, including a full-blown community Irish wake.

“It felt like there was no outlet for that conversation,” says Garbacik of what spurred the concept initially. There was “no outlet for people to kind of grieve or process this change, and no one was doing anything productive with it, artistically, to preserve memories of what came before.”

Ghosts of Seattle Past, both the book and the larger project, is ultimately an attempt to fill that void. Garbacik spoke with Atlas Obscura about what she learned along the way, and why what’s happening in Seattle should matter to urban dwellers everywhere.

For readers who aren’t that familiar with Seattle, can you describe what it’s been like to live in the city over the past five or 10 years, in terms of how rapidly things have been changing?

Well, it’s the tech explosion, part two. That’s what’s going on in Seattle. Amazon’s been adding thousands and thousands of workers. The thing to understand is that Seattle is only 684,000 people. So, when one tech company moves 50,000 people into two neighborhoods… And there are a lot of tech companies coming in.

As this happens, developers are trying to add housing and infrastructure as fast as they can. There are cranes everywhere. And it’s a boom. The median income is going up. There’s lots of new jobs, there’s start-ups, there’s new retail every day. At the same time, Seattle’s history was kind of scrappy. It was a more blue-collar city, it was a back-alley arts city. There was a lot of character, and magic happening in warehouses.

On one hand we’re getting a lot of attention in our music scene, and businesses are exploding. On the other hand, the numbers of black people and black-owned businesses are declining really rapidly, the homeless death rate is very steep and climbing. Our queer neighborhood was this really dynamic space, second only to San Francisco’s, and that neighborhood is now high-end furniture shops. And bias incidents and hate crimes are going up as well.

You can say, “Oh, it’s a growing city, it’s figuring out its new identity.” But Seattle has always been doing this. It’s always been a boom-and-bust city, and it doesn’t really look backward too much. It’s all about innovation, it’s all about the next big thing. And as a result, there’s an awful lot of communities that have experienced displacement and erasure over time, and over and over again. Right now, it’s happening so fast.

There was an Eritrean restaurant in the Central District where East African communities gathered to watch international news and catch up on the news from home. That disappeared. It’s not just that a cool dive bar is gone. It’s these gathering places, lynchpins of the community. And now, where do they go?

Tell me about putting a project like this together. How did you go about getting a diverse group of contributors?

I’ve always been involved in the music scene in one way or another, and at that time I’d been volunteering at this all-ages music and arts space called the Vera Project. The thing about Seattle is, if you’re involved in the music scene, you know everyone. And I mean everyone. You know everyone on the city council, you know everyone in the mayor’s office, you know everybody who owns a restaurant, who owns a venue. If you’re tapped into the arts scene in that way, and if you’re tapped into the nonprofit scene that way, you know a really wide range of people. So the process, honestly, is making a lot of phone calls and emailing everyone I’ve ever interacted with and saying, “Hey, who has a great story? Who should we hear from? What am I missing?”

It also helps to host events where people can come interact with it, live. One thing I did was called a Resident’s Podium for Seattle Legacy Spaces, at the Center for Architecture & Design. I called up a city council member who I know had a lot of concern about the places that are disappearing, and I said, “If you’ll fill a room with developers and city officials, I will parade a bunch of residents and artists and community organizers in front of them.” It was just, “Let’s have this conversation, let’s have it in public.” Throwing events like that was very much the key to getting a broad swath.

I had some help from my publishers as well, and, lastly, my collaborators on the project, Josh [Powell] and Jon [Horn]. We made posters and wheat-pasted them all over the city. And we just said, “We want to hear from you.” When you do it that way, and people know it’s a DIY, scrappy endeavor, and that you really want to hear from them, and that you want their art, their memories, their stories, we’ll come to your house, we’ll sit down and talk to you for four hours—people really responded to that.

Were there stories included in the book that truly surprised you?

One is “3200 W Barton St,” which is an interview with Janet Schuroll. Janet tagged something on our website, and it was this space, this bog, where her brother had drowned in West Seattle. And I was like, “Oh my god. I’m not quite sure how to approach this.” Is this a lost place? It was certainly a compelling story. What she told me, when I asked her more about it, is that where that bog is, a large community of Japanese tenants had been taking care of this field, gardening it, and these were the gardeners who supplied Pike Place Market. During the internment, they were forced to abandon that space, and it turned into a bog that wasn’t cared for. Janet’s brother died in that bog.

So we have this really unexpected way of seeing how something that is very specifically a tragedy for the Japanese population of the city is also interwoven with the health and safety of everyone else.

How did you go about balancing the long view of Seattle history with what’s been happening in the last few years?

In a lot of respects the motivation for this project is about trying to capture this specific moment, in terms of the energy and the anger and hopefulness, before it becomes complacency. We’re watching this homogenization of the cultural landscape. I’m not antidevelopment, and I’m not anti-density, I just want to see it done in a way that doesn’t push out communities of color and queer people and artists. There’s definitely a way to create a more inclusive landscape than what’s being done.

So there is a strong emphasis on what’s happening right now. That being said, the parameters I set were that someone has to remember the space that they’re talking about, they have to be alive to be able to tell the story of the space. In terms of how far back it goes, it goes back as far as the most elderly people we spoke to. For example, there’s a group of older gentlemen, mostly African-American men from the Central District who attended Garfield High School, who meet for breakfast. That’s probably the oldest story [in the book].

Having talked to so many different people, you’re in an interesting position in terms of having a sense of the collective perspective of Seattle right now. How do you think the city feels about its place in the larger context of cities grappling with this kind of change?

I think people’s sense of what’s happening is that the city is losing its soul. As soon as you start seeing ampersand restaurants—you know what I mean …

I do.

[Laughs] As soon as you see that in a town, it’s like, “Oh, hell no. It’s happening!”

But here’s the thing. Seattle has a lot of different images of itself, depending on who you talk to. That makes it difficult to give you one unified answer to this. There are a lot of people who like thinking of it as an innovator hub that keeps reinventing itself, but those are the people who don’t have as much to lose. They’re more privileged and they don’t have to worry about getting priced out. Other people think of it as this scrappy, arts-underbelly place where weird, unique things happen. And they are watching the scene disappear.

Let’s be honest, San Francisco is dead. It’s over. Nobody’s going there for the arts. Seattle is just two steps behind. It’s happening all over the country. I just heard an NPR story about the same shit in Nashville. It’s definitely happening. Part of the problem is that each city thinks that this is a thing that’s happening to them. That was a big part of the reason that I thought, “This is something that’s larger than just Seattle’s story.”

You can take a walking tour inspired by Ghosts of Seattle Past, featuring authors from the book, on Obscura Day, May 6, 2017.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook