Found: A Key Piece in the Puzzle of Giraffe Evolution

A new member of the family.

We know a few things about giraffes. They are the tallest animals on the planet, with tongues nearly two feet long, which they use to eat hundreds of pounds of leaves and buds from acacia and mimosa trees each week. And a group of them is called, appropriately, a tower. But when it comes to the evolution of their family, Giraffidae, which goes back to the Miocene—roughly 20 to 5 million years ago—there are still a lot of unknowns.

That’s because of the 30 or so species that scientists think have existed in the past, today we only have two, the giraffe and its forest-dwelling cousin, the okapi. Until now, fossilized remains of some ancient giraffid species have lacked enough skull material, and the defining characteristics they can hold.

A team of paleontologists led by María Ríos from Madrid’s National Museum of Natural Sciences recently unearthed the well-preserved remains—including the skull—of a previously unidentified member of the family, dubbed Decennatherium rex. The D. rex, found at the fossil site of Cerro de los Batallones, just outside of Madrid, adds a key piece to the puzzle of giraffid evolution, and suggests that though giraffes and okapis are each other’s closest relatives, they are still from far sides of the family tree. “We’re preserving relics of two very distinct groups of giraffes that were morphologically very different,” Ari Grossman, of Midwestern University in Glendale, Arizona, told the New York Times. Ríos and her team announced the discovery in a paper in the journal PLOS ONE.

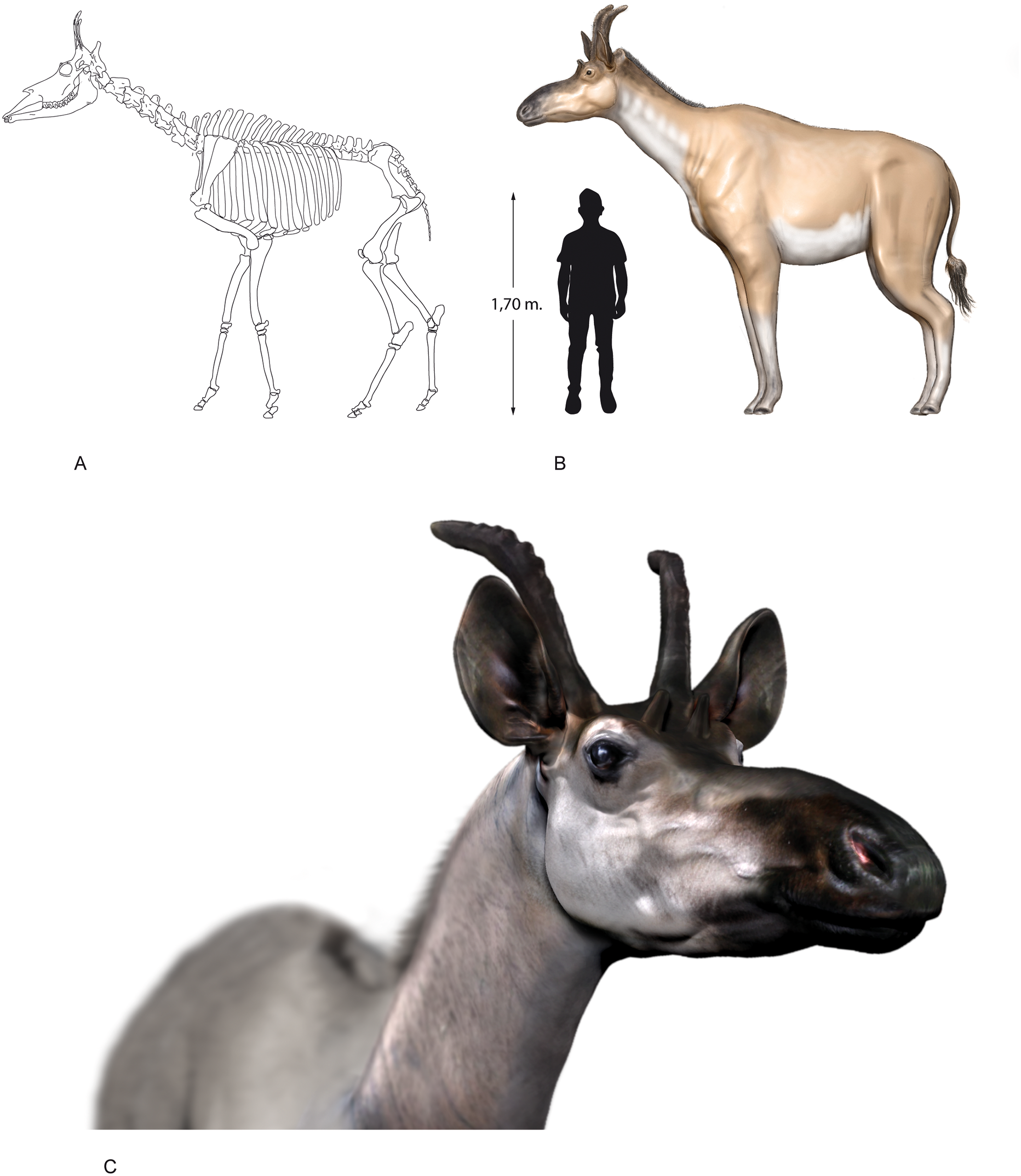

Remains of three other examples have previously been unearthed in Spain, but none had the skull, which made assigning them to the species difficult. Male D. rex were probably about nine feet tall and about two tons in weight—putting them right between their surviving cousins in terms of size. Unlike their descendants, they had two, rather than one, set of horn-like structures called ossicones: a short pair above the eyes and a second, longer pair that swept up and back. They also had long, flat snouts, more reminiscent of a moose than a giraffe. Notably, the site of the discovery extends the range of giraffids to the Iberian Peninsula, perhaps making them a genetic link between other members of the family in Europe and Africa.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook