The Great Antarctic Escape

How Spanish scientists and soldiers made an epic journey home as the world locked down around them.

On March 11, the World Health Organization announced at a news conference in Geneva, Switzerland, that the coronavirus outbreak had officially become a pandemic. A few days later, and over 8,000 miles away, the Spanish scientific research vessel Hespérides was blasting through 16-foot-high waves in the Drake Passage, the tempestuous waters between South America and Antarctica.

Its passengers, around three dozen scientists and military personnel, had been evacuated from two Spanish research bases in Antarctica—and they found themselves in a race against the imminent closure of the world. If they didn’t reach Argentina before its borders were shut and its flights were grounded, they risked being stranded in a far-flung harbor while a highly infectious virus stampeded across the planet.

While most of us had spent several weeks beginning to come to grips with the enormity of the COVID-19 crisis, those aboard the Hespérides were leaving the only continent on Earth not to be touched by it. Should they make it to shore, they were to be thrust into a world transformed, one that made their journey home to their families newly perilous. For many of them, the coronavirus itself was a greater source of fear than being inadvertently imprisoned at the icy ends of the Earth.

Their voyage would be an improvisational gauntlet, one in which every on-the-fly navigational decision could make the difference between success or failure, home or the unforgiving sea, staying healthy or risking bringing the virus home to their loved ones.

Shortly after the beginning of the new year, it was business as usual in the South Shetland Islands, a series of rocks 60 miles north of the Antarctic mainland. The archipelago’s Livingston Island was powdered in a typical sprinkling of diamond dust snow as temperatures danced just above freezing. Land-bound, spiraling sentinels of blue-tinged ice watched deeper-blue bergs drift by in the frigid waters.

Jordi Felipe Álvarez, head of Livingston’s Spanish research base, Juan Carlos I, arrived in mid-February. The base, crewed only in Antarctica’s summer months, was populated by a small crowd of scientists going about their day. “Everything was perfect. Everyone was in a good mood,” he says.

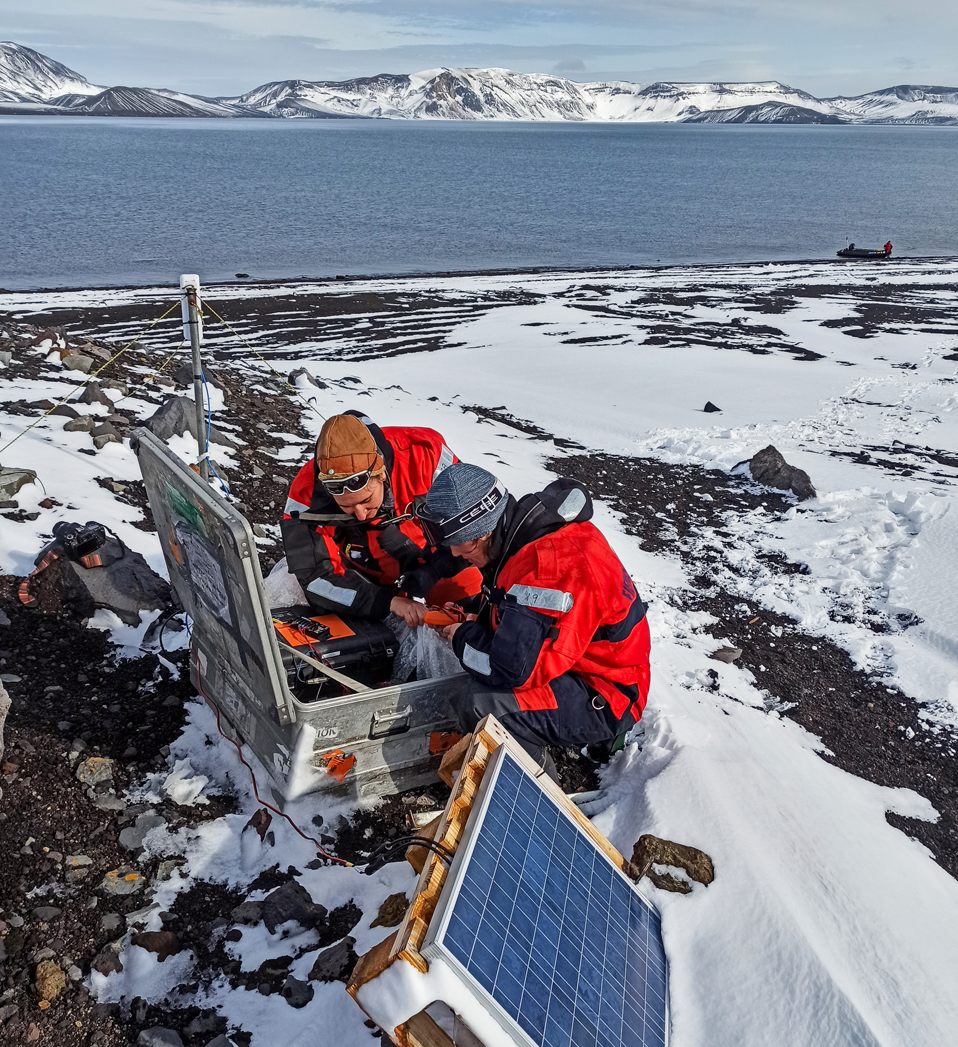

The same was true at Spain’s Gabriel de Castilla base on neighboring Deception Island. Carved with a cauldron-shaped scar, the result of a cataclysmic eruption 4,000 years ago, this isle—home to geothermally heated black sand beaches often filled with chinstrap penguins—provided a fantastic platform for all sorts of research.

Itahisa González Álvarez, a doctoral student in seismology at the University of Leeds, had arrived on Deception at the end of January. Her job was to monitor the seismic activity of the island’s active volcano. For a while, things proceeded normally.

But by late February, a worrying number of coronavirus infections had popped up in Europe. Messages of concern from people back home and a torrent of online articles about the coronavirus—not all of them reliable—made their way to the bases. “It seemed bad,” she says, “but of course we couldn’t imagine how serious the situation would become.”

In early-March, flights were being grounded with increasing frequency. Europe had become a locus for the pandemic, as Italy went a nationwide lockdown and 10 other European countries began closing their borders. It was all but inevitable that Spain would join them.

A visceral sense of dread washed over both bases. As many fretted over the safety of their friends and families, and as the Spanish government began plotting its next move, the scientists and military staff began to wonder if they would be stranded in Antarctica indefinitely. Those in other state-run Antarctic research bases were toying with the idea of remaining on the white continent throughout the increasingly cold months to come, while others were hoping to be sped to safety by ad hoc repatriation efforts.

Ushuaia, a port in southern Argentina, is a common transit point for Antarctic researchers, but the country was also thinking of closing its own borders. Fearing the worst, the Spanish authorities decided to send Hespérides, a Spanish Navy–operated scientific research vessel docked in Chile, to Antarctica and get the staff from both bases to Argentina before it was too late. If they would be trapped, better there than across Drake Passage.

The date for the ship’s arrival kept being pushed up—from March 19 to March 16. Then, on March 12, the bases found out it would arrive in just two days. Normally, staff would have a week to shut everything down and shield all the scientific equipment and living quarters from the harsh Antarctic winter. This time, they had a single day. González Álvarez and her colleagues ran around Deception’s volcanic cauldron, retrieving their seismic monitoring equipment in violent wind. Others scrambled to pack up not just their own equipment, but all their food, medicine, and trash, too.

On Livingston, the base physician was asked to prime everyone for a return to a now-coronavirus-controlled world. Felipe Álvarez, a biologist by training, knew the risks of infection and understood how to safely wear and remove face masks and gloves. Others on the base were less up to speed, so they were given a crash course in biosafety and malevolent microbiology. Felipe Álvarez recalls them being told: “You cannot see it, you cannot feel it, but it can affect you in a hard way.” It was like preparing to land on another planet.

Hespérides arrived as scheduled, collected the staff from both bases, and began charging back toward Ushuaia the next day. The voyage took three days, most of it through a tempest angrily juggled the boat like a cork. “Regular meals in the cantina were even suspended on the second day, as it was essentially impossible to eat normally,” says González Álvarez.

They arrived, unharmed, in Ushuaia, only to find they were too late. The borders had closed and all outgoing flights from Argentina had been suspended. They were asked to remain on the ship. COVID-19 cases had appeared in Chile even before the boat had left for Antarctica, so the Argentinian authorities didn’t want to risk anyone potentially infected onboard entering the country. “We were treated like we were completely dangerous,” says Felipe Álvarez.

The two remaining options were grim: take Hespérides across the Atlantic—a month-long voyage—or head to Brazil. The country hadn’t yet completely shut down, and flights were still leaving São Paulo, but it would take two weeks to get there.

Unsure they would make it to Brazil before it, too, entered lockdown, those on board, like those of us stuck at home, began to think of ways to keep everyone’s spirits up. There were guided tours of the ship and yoga classes. “I taught English three times a week,” says González Álvarez. “A few people offered to cook a huge paella for everyone on a Sunday,” and they voted on which movies to watch each night.

During their sprint to Brazil, whispers began of a Hail Mary: The Spanish government was talking to Uruguay—the nation sandwiched between Argentina and Brazil—to help repatriate Spanish citizens. The rescue plan wasn’t set, but they headed to the Uruguayan capital, Montevideo, on March 25, and had to wait for two days in the waters just outside its harbor.

That day, they found out the plan was officially a go: On March 28, a passenger jet would fly them all to Madrid. The collective mood had noticeably lifted, and the day before they had a barbecue on the deck. But on the morning of the flight, anxieties ran high again. The last thing everyone did, says Felipe Álvarez, was shake hands. After that, they were told, the rule was six feet.

By that time the scientists had spent at least 45 days away from civilization. The military personnel had been in Antarctica for three months. And while everyone was keen to get home, they were deeply anxious that they would contract COVID-19 en route and bring it home to their loved ones. Some considered staying behind on the ship, but at the polite-but-firm insistence of the Spanish Navy, “All 37 of us left,” says Felipe Álvarez.

They were handed masks, gloves, and small bottles of hand sanitizer. Loaded on two buses, the police then sped them to the airport in a motorcade. “It was like you’d see in the movies,” says Felipe Álvarez. “We felt more like prisoners moving from one cell to another.”

Airport security was less intense than usual, with strange-looking electronic devices allowed to stay in people’s bags. The flight, run by the airline Iberia, was packed: Other European citizens stuck in Montevideo were allowed to board as well. No seats were empty. Those without proper masks did what they could. Some wore the diving masks they had brought on vacation.

Trying not to touch anything on a 12-hour flight was a thoroughly unnerving experience. “Going to the bathroom was silly,” says Felipe Álvarez. He went only twice, having decided it was safer to stay seated. Food and drinks were served. People ate. Nerves frayed. “You had this kind of freaky situation where you didn’t know how to act,” he says.

The flight landed on March 29, and everyone went their separate ways.

Felipe Álvarez drove home to Barcelona. He saw a few dozen cars on the roads at most. “There were rabbits on the highway,” he recalls. When he arrived, the city’s normally cacophonous streets were all but deserted. “It was like every single movie we watched since we were teenagers about the zombie apocalypse.”

He got to his apartment, greeted his exhilarated family from behind the door, and immediately decontaminated himself in the shower. He put his luggage out on the terrace to be sterilized by the Mediterranean sun for a week. He quickly adjusted to life back home while embracing a new challenge: helping his wife home-school their young daughters who, under Spain’s lockdown rules, weren’t allowed outside at all.

González Álvarez didn’t have much time to think when she disembarked in Madrid. She had to run to another terminal to make a connecting flight to Tenerife, in the Canary Islands off the coast of West Africa, where she lives. Just four other passengers were on that flight with her. “It felt really sad and weird to not be able to properly say goodbye to everyone after all we had gone through,” she says. Upon landing, her temperature was checked by Red Cross staff before she was allowed to leave the airport.

She didn’t go to her family right away. Her parents, her partner, and his mother all have underlying conditions that put them in a high-risk category for COVID-19. Not wanting to risk infecting them, she spent the first two weeks in Tenerife alone, at a friend’s house. Even after rejoined her partner, her isolation wasn’t dissimilar from her Antarctic experience—and the experience that many of us have become strangely familiar with. “The only contact I have with other people is through screens,” she says.

But it’s more extreme in some ways than Antarctica. On Deception Island, she had the sight of penguins and sea lions lounging about outside. She is nostalgic for that, just as she is nostalgic for the time when she simply could go for a walk in her neighborhood.

“It feels a bit strange,” she says. “The world we came back to is not the same we left.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook