How a Hole Punch Shaped Public Perception of the Great Depression

The notorious photo editor who introduced “America to Americans.”

From his office at the Farm Security Administration (FSA) in Washington, D.C., Roy Stryker saw, time and again, the reality of the Great Depression, and the poverty and desperation gripping America’s rural communities. As head of the Information Division and manager of the FSA’s photo-documentary project, his job was to hire and brief photographers, and then select images they captured for distribution and publication. His eye helped shape the way we view the Great Depression, even today.

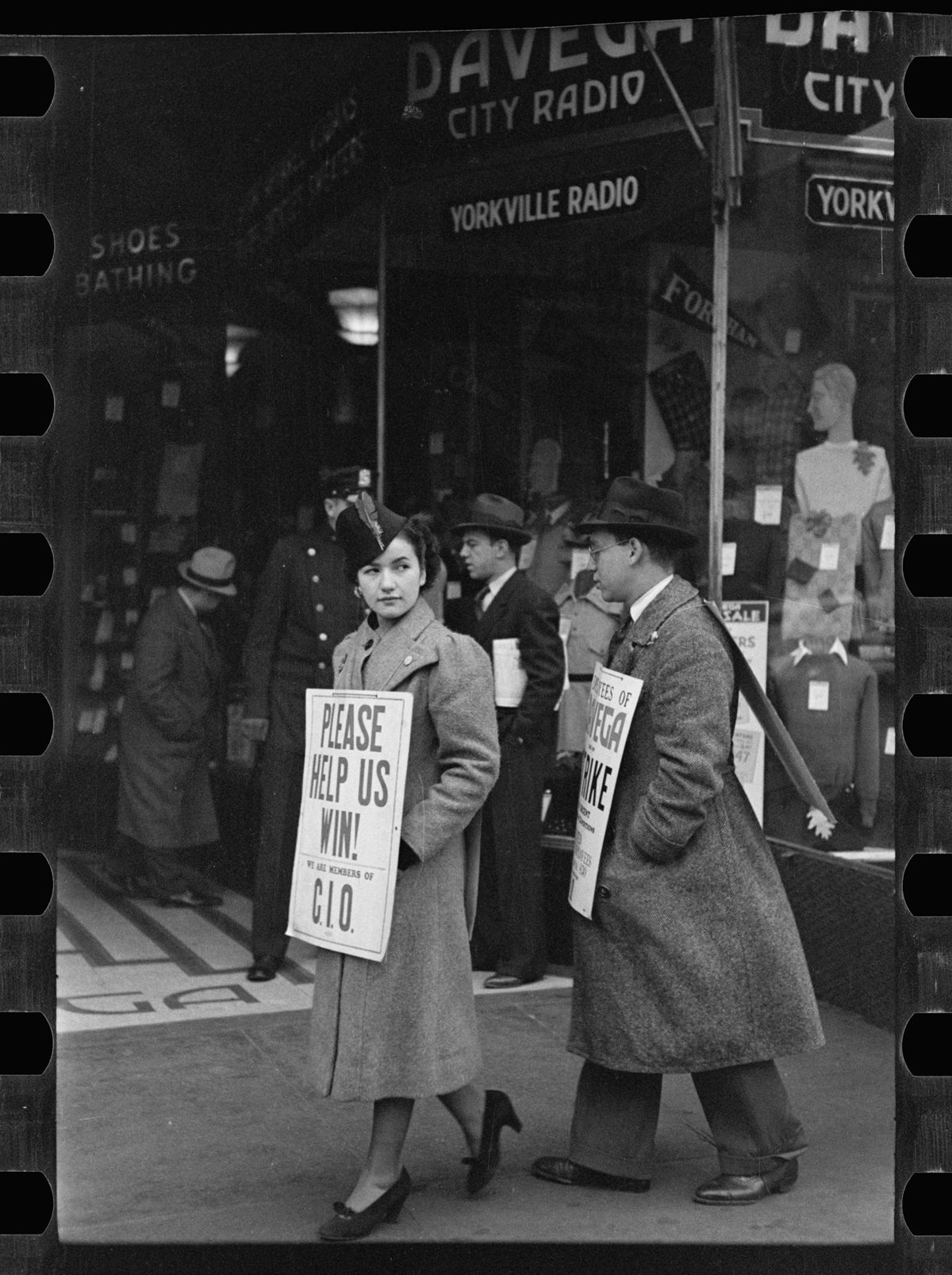

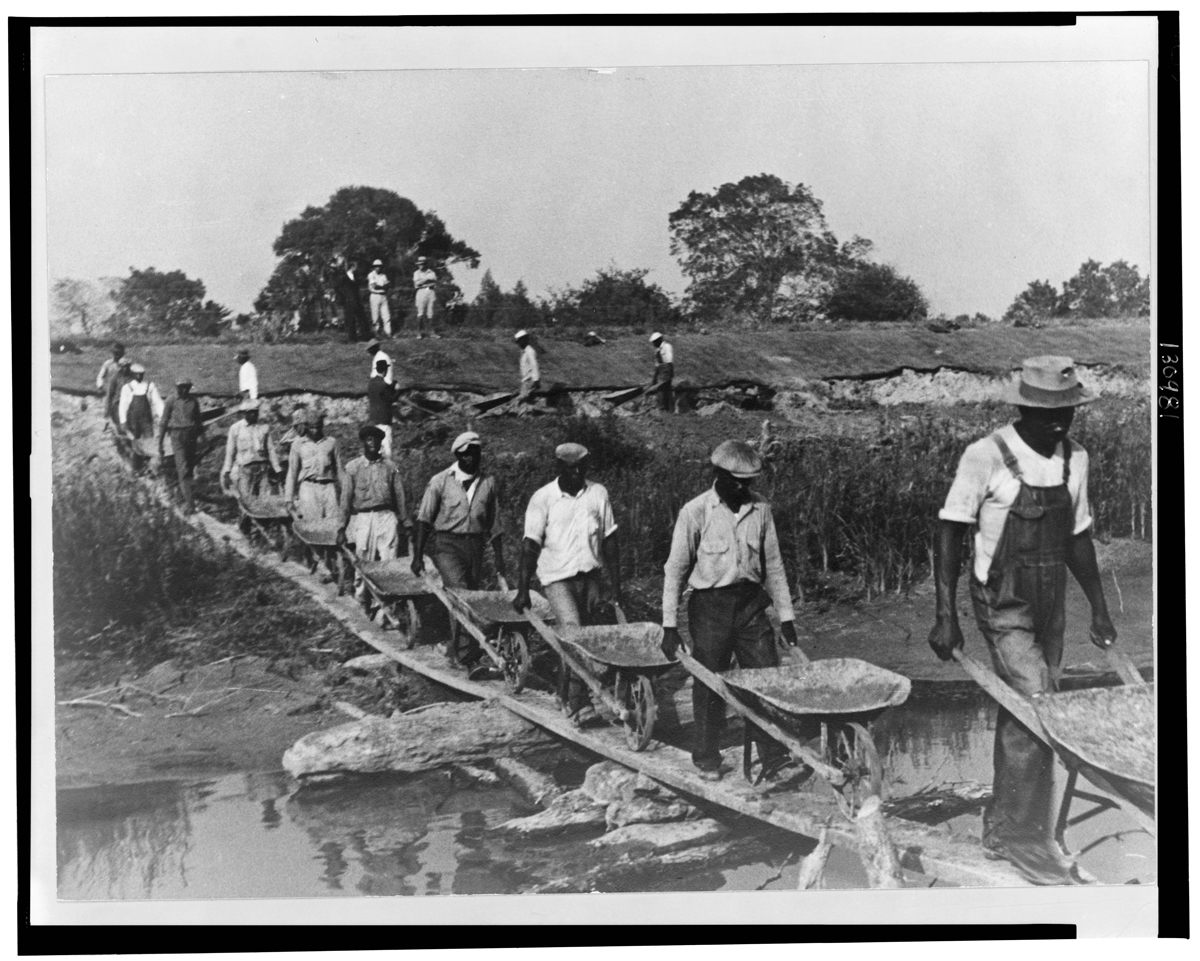

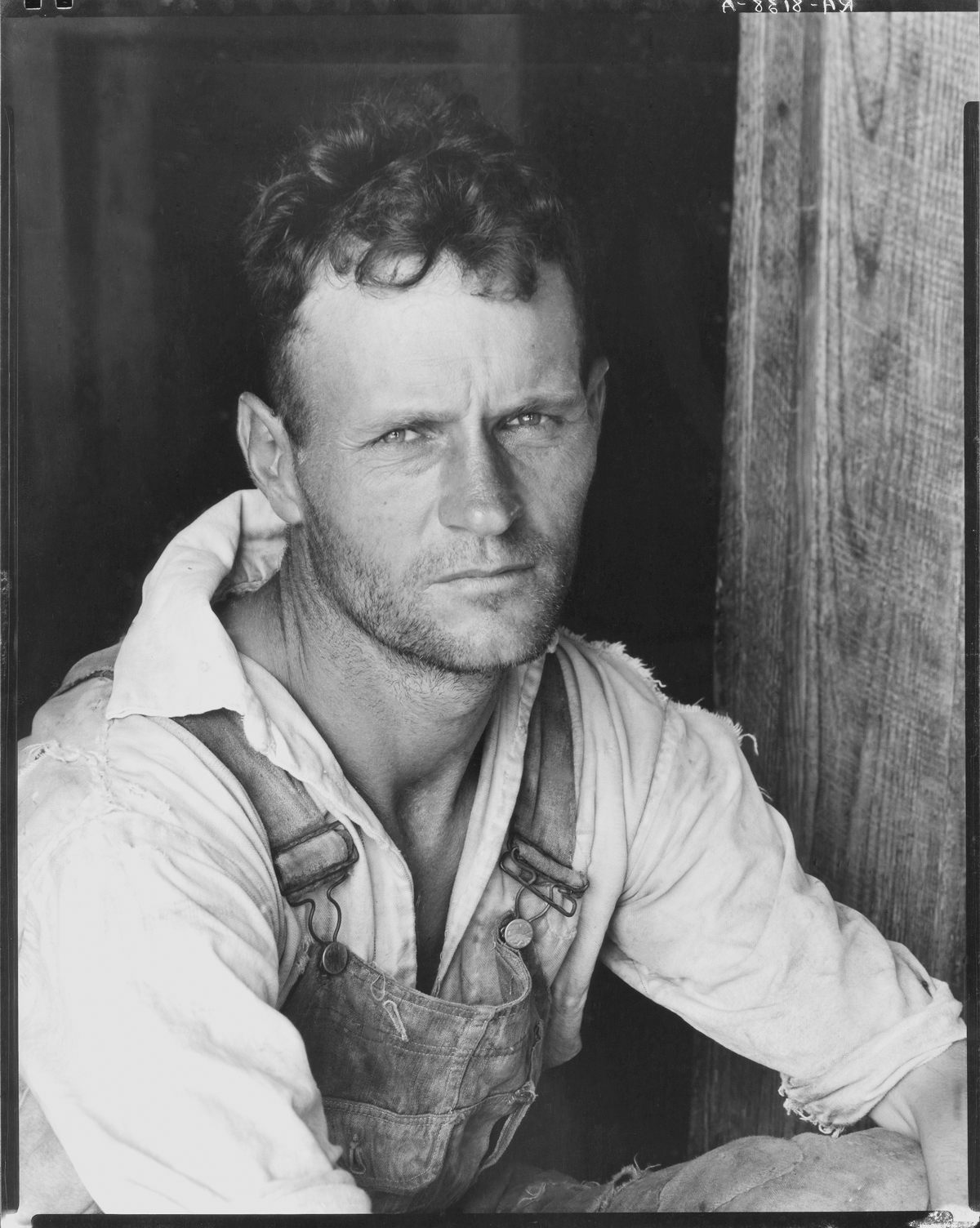

Professionally, Stryker was known for two things: preserving thousands of photographs from being destroyed for political reasons, and for “killing” lots of photos himself. Negatives he liked were selected to be printed. Those he didn’t—ones that didn’t fit the narrative and perspective of the FSA at the time, perhaps—were met with the business end of hole punch, which left gaping black voids in place of hog’s bellys, industrial landscapes, and the faces of farmworkers.

In 1935, the Resettlement Administration (RA) was established as part of the New Deal to provide relief, recovery, and reform to rural areas. The FSA, created in 1937, was its spiritual successor. The FSA’s duties included, but were not limited to, operating camps for victims of the Dust Bowl, setting up homestead communities, and providing education to more than 400,000 migrant families. Communicating about its efforts was also part of its mandate.

Prior to the dissolution of the RA, its head, Rexford Tugwell, lured Stryker, a fellow economist and amateur photographer, to Washington to be involved with the agency. According to James Cletus Anderson’s Roy Stryker: The Humane Propagandist, he instructed Stryker to “show the city people what it’s like to live on the farm,” and what became the FSA’s documentary photography project was born. The goal was to introduce “America to Americans,” and keep public opinion, especially in the cities, favorable toward the New Deal.

Until that point, the U.S. government had appeared largely uninterested in supporting the economic security of its citizens, unlike some other countries at the time. Public sentiment was that the government doesn’t owe you anything: no federal minimum wage, no social security, no system of low-cost healthcare. If you were broke, you were on your own.

In 1932, Herbert Hoover’s sluggish response to the burgeoning economic crisis handed Franklin D. Roosevelt over 80 percent of the vote. Though many programs of his New Deal were temporary (Civilian Conservation Corps, National Recovery Administration, Works Progress Administration), others continue to this day, including the Social Security Act, the Fair Labor Standards Act, and what would eventually become the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Roosevelt’s policies were met with opposition, on the foundation that state welfare went against America’s individualistic nature. To combat this, supporters of the New Deal wanted to show just how dire the situation had become, and illustrate the necessity of intervention. According to various sources, urban Americans had a hard time understanding the intense suffering in the countryside. “Seeing is believing” had long been used as a tool for social reform, and Stryker believed in its power.

Stryker sought out photographers, among them Dorothea Lange, Gordon Parks, and Arthur Rothstein, and made their images readily available to the press. Given the lack of new photography and art being produced during the Great Depression, the photos regularly appeared in magazines such as LIFE and Look. He also had them displayed at the 1936 Democratic National Convention, the 1936 World’s Fair, the Museum of Modern Art, and other prominent venues. The publication of a series of early photographs, including Lange’s Migrant Mother, proved instrumental in pushing the federal government to provide emergency aid to migrant workers in California.

In the effort to represent the FSA and Roosevelt’s signature domestic achievement in a positive light, the chosen photos captured how the idealistic views of farm life were being tainted by poverty, and how the FSA programs were helping farmers reclaim their dignity. Common elements were decrepit housing conditions, the lack of food and clean water, and harsh work environments.

It was government propaganda, and there were certainly some within the government (both supporters and detractors) who saw it that way, and more who considered both the FSA and its photography project as communist and un-American. In a 1972 Interview, Stryker admits to having felt political pressure from the Department of Agriculture to portray the effectiveness of the New Deal. “Go to hell,” was his response. His photographers “were warned repeatedly not to manipulate their subjects in order to get more dramatic images, and their pictures were almost always printed without cropping or retouching.”

But there is a way to manipulate the story being told without altering the images themselves—the process of photo editing, of choosing which images to highlight and which to discard. And this Stryker did with a particular zeal. He was known to be “a little bit dictatorial in his editing,” recalls Ben Shahn, a photographer who worked with him, in an interview from the time. Many photographers both appreciated and disliked him. Lange called him “hospitable” and a “genius,” and Parks stated in an interview that they all owed “a great deal of thanks to Roy for what he did for us,” but also acknowledged that “there were times when I thought he was a real mean hombre.” Others, including Walker Evans, did not get along with Stryker at all, and left the project over his ideological differences.

Stryker never said why he killed certain photos and kept others, or why it was necessary to ritualistically kill negatives with a hole punch. But a review of the killed images, which survive in digital and physical form in the Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives Collection at the Library of Congress, reveals some of his preferences. The most prominent feature of the photographs is illustration of the resoluteness of the “American Spirit,” and the rugged individualism of rural families. These images appear to depict the New Deal as a leg up for struggling Americans, rather than a crutch for the lazy. Empathy and subject-viewer connection are also strong themes, as is inviting viewers into the subjects’ private spaces and moments.

Another theme is scale, including images that show a larger setting or environment, or that capture communities as a whole. Stryker also tended to kill images with people smiling. Interestingly, it is possible in the collection to see sets of images depicting the same subjects—such as the portrait of the washerwomen below—in which Stryker chose somber moments over moments of levity. These are clear cases in which the story of the photos is dictated by the editor’s hand. Given the choice between pathos and smiles, Stryker put a hole in any image that could leave city-dwellers with clear consciences. And sometimes, he just chose the best image.

After the beginning of World War II reoriented the country’s efforts, the FSA became the Office of War Information (OWI). Stryker grew concerned that the images that he had fought so hard to insulate from political influence might be misused by the OWI, so he used his still-substantial political clout to ensure the images were preserved in the Library of Congress.

Today, more than 170,000 prints are publicly available. Not only do they offer a peek into lives that most Americans know little about, they continue to inspire documentary photographers and serve as a reminder of how easily dissolution and desperation can become regular presences in American life.

From this vast collection, Atlas Obscura has curated a selection of Stryker’s hole-punched photographs below, each above its approved counterpart.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook