The Painted Panoramas That Will Make You Yearn for Yosemite and Dream of Denali

Step into Heinrich Berann’s sweeping portraits of America’s national parks.

With the alarming exception of rapidly receding glaciers, most eye-popping features of America’s national parks don’t change too often—grand chasms and clusters of giant sequoias don’t usually appear or vanish overnight. Still, maps of these landscapes are updated fairly frequently—every year or so for heavily trafficked places, or every couple of decades for remote ones. The tweaks might be minor (a new campground here, a fresh parking lot there) or a lot more substantive.

Over the last quarter century, the National Park Service (NPS) has used new data, including satellite imagery and land cover information compiled by the U.S. Geological Survey, NASA, and the Department of Agriculture, to produce engaging maps that help visitors picture a landscape’s features. Sometimes this involves shifting perspectives. Other times it might call for natural color, from the dark, blueish green of a coniferous forest to the warmer, lighter tones of a deciduous one. That’s “essentially painting by the numbers,” says Tom Patterson, a retired NPS cartographer—in service of helping visitors better understand a sprawling environment. The NPS has a classic example of how such flat representations can accentuate the majesty of its holdings: Heinrich Berann’s impossibly detailed, slightly fantastical painted panoramas.

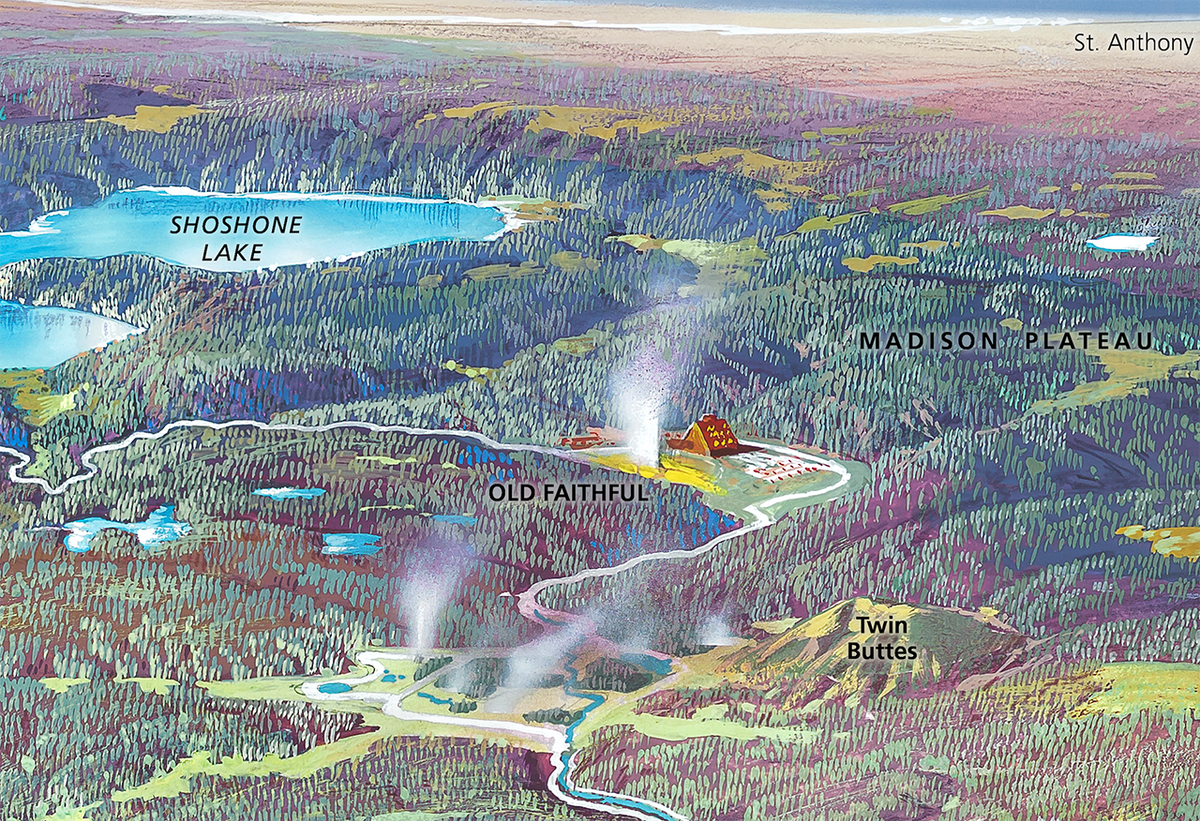

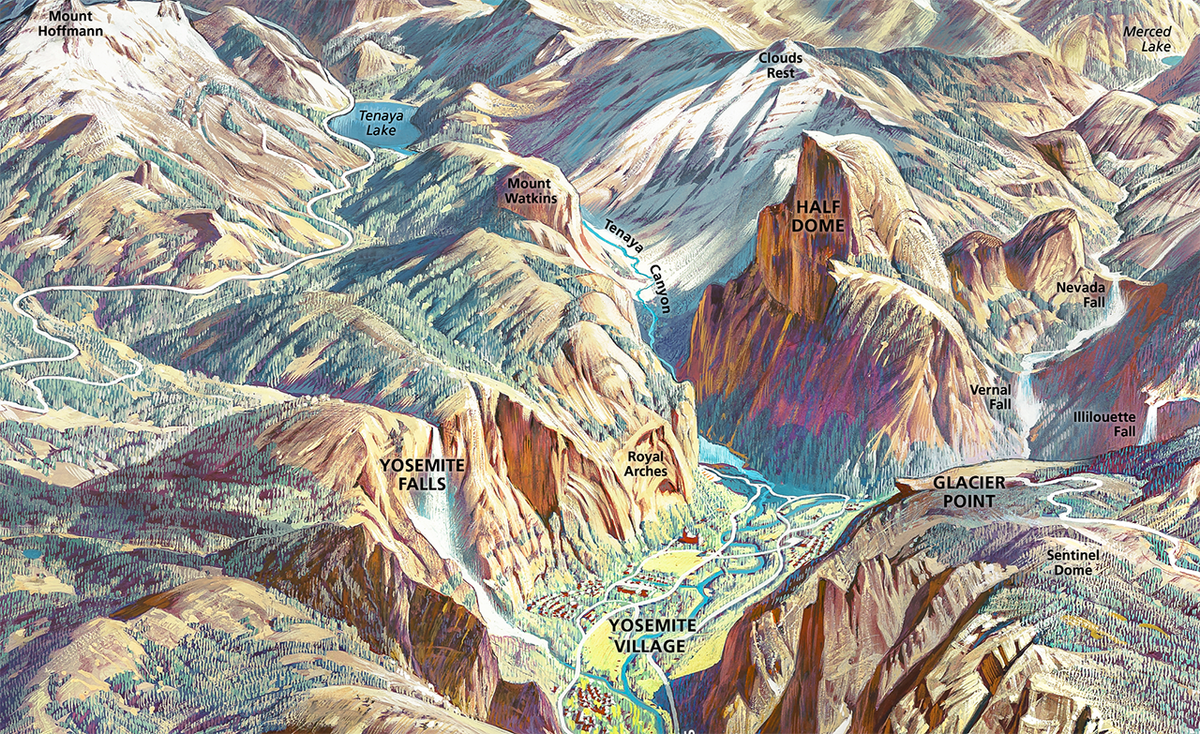

Berann, an Austrian artist known for his sweeping, often snow-cloaked landscapes, made four grand paintings of American national parks between 1987 and 1994. (The paintings, each a little more than three feet wide, have recently been digitized in high resolution, available on the NPS website, with and without labels, to show every tree, snowdrift, and brushstroke.) Berann began with North Cascades National Park in Washington State, “the closest landscape in the lower 48 to his native Alps,” says Patterson. The artist then worked his way through Yosemite and Yellowstone before wrapping up in Denali, in Alaska.

The paintings are astonishing—at once rugged, creamy, and saturated—and even after thinking about them for decades, Patterson is still slack-jawed that Berann pulled them off. (He even has a reproduction of one of Berann’s European landscapes in his living room.) “I know all the steps this guy took to make those things, but I’m still astounded that he was able to do it,” Patterson says. Without the digital elevation models and 3D rendering tools that aid cartographers today, he adds, Berann “was relying on topographic maps, aerial photographs, and, if he was lucky, a scenic flight over the park.”

Before Berann began each painting, the NPS communicated a few instructions. At Denali, for instance, they requested that the panorama include Mount McKinley (now called Denali) and several other peaks in the Alaska Range, plus the roads and railways leading to attractions that guests might want to seek out, including the visitors’ center and nearby hotels. Otherwise, Berann “more or less had free hand in what he did,” Patterson says. The NPS team seemed to trust him and respect his vision. According to Patterson, Vincent Gleason, the former NPS publications director who commissioned the panoramas, was enamored with work like Berann’s, which reflected a mastery of finicky, fastidious, careful craft. Berann’s paintings had been printed in National Geographic and elsewhere—he was “a well-known, famous guy who was out there,” Patterson says, so recruiting him for NPS projects probably felt like “a feather in Gleason’s cap.” That respect for Berann’s work comes through in letters between him and Herwig Schutzler, a commercial contractor with R.R. Donnelley Cartographic Services, who mediated Berann’s relationship with the NPS. “They had a long and detailed and often very flowery correspondence, often in German and very formal,” Patterson says. “Very old world. It seemed like it was almost from the 19th century.” Berann submitted sketches to the NPS for sign-off. Once he made any requested tweaks, he got down to painting.

That’s where the panoramas came alive. Color, as Patterson put it, “metamorphosed Denali from a mechanical drawing into a beautiful landscape.” The artist washed gouache and tempera over light pencil sketches drawn on heavy, coarse white paper, and filled in the landscapes from there, working on one swath of terrain at a time. First, he laid down the background, then he built up dark pools of shadows, which emphasize the peaks. He added clouds—wispy or foreboding—and water—stagnant or rushing, and often glittering, speckled with white. Skinny details, such as rivers and roads, came last. Between research and painting, Berann spent months, even years, on each panorama.

The paintings have a dizzying, dreamy quality, but they’re light on geographical rigor. Because Berann “took liberties” with details, Patterson explains, the panoramas “have almost zero scientific value.” (In a paper published in the journal Cartographic Perspectives in 2000, Patterson affectionately describes their air of “relaxed accuracy.”)

No matter: Fidelity wasn’t really the point. Usefulness and wonder were. Across his panoramas, Berann tinkered with scale and grade. He widened Yosemite Valley so viewers could appreciate Yosemite Falls, Illilouette Falls, Vernal Falls, Half Dome, and more, all in one view. He also radically exaggerated some peaks and enlarged human-made features such as Yellowstone’s Old Faithful Inn, which would otherwise be lost in the landscape. As Betsy Mason reported in National Geographic in 2018, Berann also sometimes repositioned mountains to show off their best angle, such as when he “swung [Wyoming’s Grand Tetons] to the east to reveal the most iconic view of the range, rather than the end-on view that would exist from the viewer’s vantage point in real life.”

Berann’s panoramas afforded viewers “an airplane-window view,” Patterson explains. The artist’s vista encompassed more than one person would ever actually be able to take in. “With a Berann landscape, you can see it all,” Patterson says. “Kind of.” The perspective doesn’t show the backsides of mountains or canyons, but it crams a lot of visual information into a fairly small space and, for all its invention and creative liberties, feels natural and real. The result, Patterson suggests, is easier to understand than an even a fully accurate aerial photograph. “If you look at a place like the North Cascades, it’s mountain peak after mountain peak,” he says. The panorama of the park, on the other hand, makes sense of a chaotic landscape of massive, similar-looking features.

Berann’s colors aren’t exactly natural. “They’re gaudy,” says Patterson, “but all come together in a magnificent way in the end.” His approach has gone on to inform some of the NPS’s other recent mapping techniques, though, including the move to 3D oblique views, which Patterson calls “a rather big change partially attributable to Berann.” Take Wrangell-St. Elias National Park in Alaska—roughly the size of six Yellowstones and home to more than half of the tallest peaks in the United States, including Mount St. Elias, which reaches more than 18,000 feet. Maps of the park now offer more detail about what those vertiginous heights look like. For visitors, these peaks often out of view in the distance, swallowed by vegetation on the shoulders of the main park road.

This tactic follows Berann’s lead of capturing the spirit of a place—grabbing the viewer’s hand and saying, “Hey, come look at this, and prepare to be amazed.” They bottle the magic that keeps people coming back to these special places, year after year, in perpetual awe.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook