The Not-So-Chill History of Hawai‘i’s Breeziest Shirt

The aloha shirt has many possible inventors and a long, fraught cultural history.

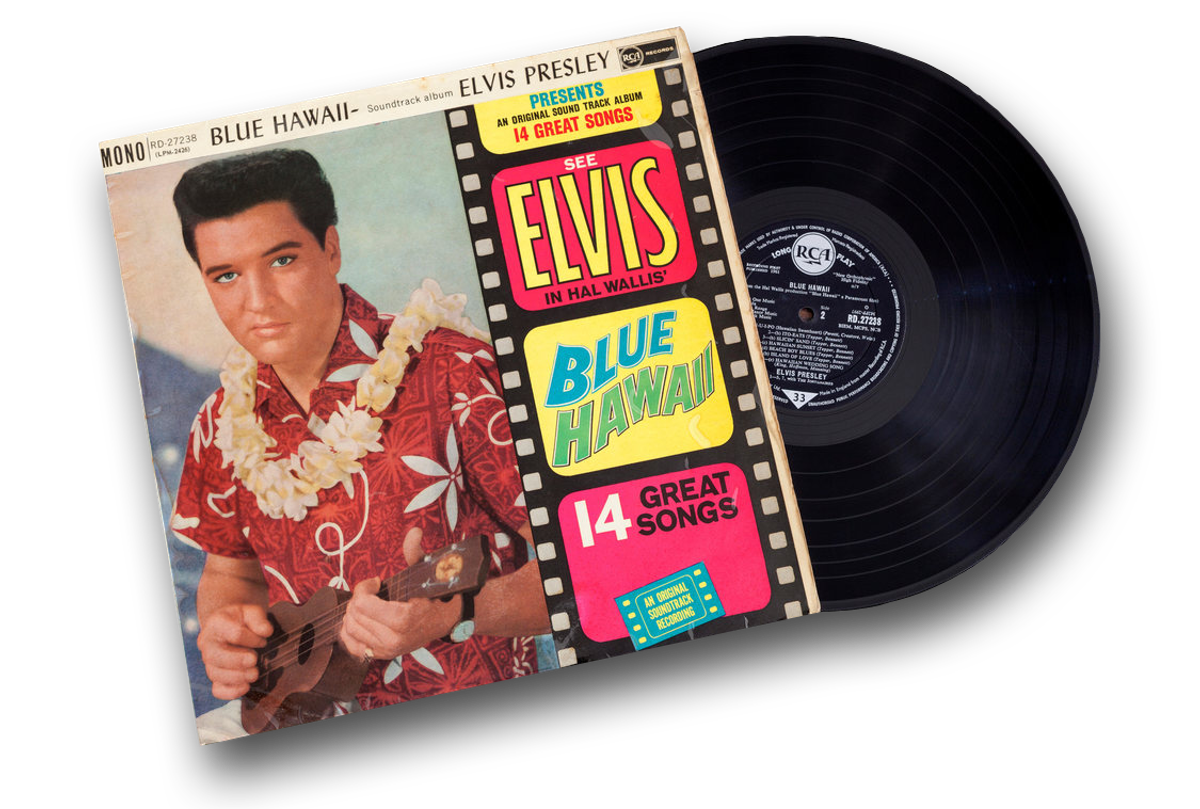

On the cover of his 1961 album Blue Hawaii, Elvis Presley can’t help but look impossibly cool. It’s not just the bouffant or half-smirk, or the plumeria lei draped ever-so-effortlessly around his neck, or the ukelele dwarfed in his large hands. No, it’s the shirt—a red zinger of a Hawaiian shirt, also known as an aloha shirt, with white tendriled flowers scattered over a woodblock print.

The chillest shirt style in the world has a murky, hotly contested provenance. No one can agree who invented the aloha shirt, according to Dale Hope, the owner of the Kahala shirt company (“The Original Aloha Shirt since 1936”) and author of The Aloha Shirt: Spirit of the Islands. But many have tried to own the shirt as a claim to fame.

First and perhaps most notable is Ellery J. Chun. The son of Chinese immigrants, Chun returned to Hawaiʻi after graduating from Yale University in 1931 to manage his family’s dry goods store in Honolulu, according to his 2000 obituary in The New York Times. He saw local Japanese teens wearing shirts made from rayon, and local Filipino boys wearing colorful barong shirts. When the Great Depression hit, Chun changed the store’s name to King-Smith Clothiers (to attract non-Chinese customers) and began selling shirts cut from flashy Japanese kimono material.

As Chun told the Atlanta Journal and Constitution in 1976, “[T]here was no authentic Hawaiian material in those days so I bought the most brilliant and gaudy Japanese kimono material, designed the shirts, and had a tailor make a few dozen colorful short-sleeved shirts, which I displayed in the store window with the sign ‘Hawaiian shirts.’” As he remembered it, this happened sometime around 1932 or 1933, before he patented the term “Aloha Shirt” in 1937. Key words: “as Chun remembered it.”

Elsewhere in downtown Honolulu, Koichiro Miyamoto took out an ad advertising “aloha” shirts in the Honolulu Advertiser, starting on June 28, 1935. It was the first documented use of the term. Miyamoto had been running his late father’s dry goods shop, called Musa-Shiya Shoten, for over a decade, a storefront almost hidden in an obscure part of town near the river and the local fish market.

Miyamoto had been in the shirt-making business ever since 1920, when he received five years’ worth of English textile orders (that he’d placed annually but were delivered en masse), according to an article published in Printer’s Ink in 1922. He later learned this delay was caused, rather inconveniently, by World War I. To get rid of this stockpile of fabric, Miyamoto began advertising custom-cut shirts in local Honolulu papers as early as 1922.

According to Dolores Miyamoto, the tailor’s wife, the actor John Barrymore came into the couple’s store in the early 1930s and pointed to a bolt of yukata cloth, a lightweight fabric used in some kimonos, and asked if they could turn it into a shirt. In the years following, Miyamoto began advertising these yukata shirts as “aloha” shirts. In every ad, Miyamoto included the logo of his store: a racist caricature of a smiling Japanese man clad in a kimono, known as Musa-Shiya the shirtmaker.

The dueling origin stories have not become more settled over time. After the Honolulu Star Bulletin ran an article on September 16, 1984, attributing the first commercially produced aloha shirt to Chun in 1936, the contrarians came out. Robert C. Schmitt, Hawaiʻi’s first state statistician, pointed out Musa-Shiya Shoten’s advertising history, citing his own work on the subject, published in the 1980 edition of the Hawaiian Journal of History.

One Margaret S. Young also wrote in to the Star Bulletin to say she remembered things a little differently. She mentioned a classmate, Gordon S. Young (no relation), who developed a pre-aloha shirt in the early 1920s, which his mother’s dressmaker had fashioned out of yukata cloth. Young said Gordon took a supply of these shirts to the University of Washington in 1926 and made a tropical stir the Pacific Northwest.

There are, of course, many other origin stories. Rube Hauseman claimed to have made the shirts for the original Waikiki beach boys, Hawaiians who worked for beach clubs on the waterfront and taught tourists how to surf and canoe. Hauseman said he used fabric purchased from Musa-Shiya, though he called them “rathskeller shirts,” after a celebrity-studded bar that they all hung out in, Hope writes. Ti How Ho, the owner of Surfriders Sportswears Manufacturing, claimed to have made and sold his first Hawaiian shirts, in his retail store in the heart of Waikiki in 1934. Other claims notwithstanding, Chun’s name seems to have stuck around the longest. Maybe he really was the first, or maybe he was a businessman savvy enough to jump on a patent and manage the narrative.

Either way, the aloha shirt kept growing in popularity, particularly among tourists. After World War II, U.S. servicemen returned to the mainland wearing aloha shirts, Linda Arthur, a textile and clothing expert from Washington State University, told Collector’s Weekly. Clothiers devoted exclusively to the aloha shirt had begun churning them out, among them Alfred Shaheen, often credited with turning the shirts into art.

Though the very first aloha shirts depicted traditionally Japanese themes, designers began incorporating imagery from Hawaiʻi in what was called a “hash print”—a nod to food made by throwing whatever was left over into a pot: beaches, palm trees, surfboards. The most obvious prints were emblazoned with repeating ribbons of “Aloha” or “Hawaii.” They may not have been elegant, but they were certainly on brand.

Beginning in the 1950s, Shaheen hired actual artists to design his shirts. He sent the designers on trips throughout Asia and the Pacific. The result was elegant, splashy shirts that incorporate motifs from around the Pacific. Shaheen went on to design the iconic “Tiare Tapa” shirt form that Elvis wore on the Blue Hawaii cover. An artist named Elsie Das also helped pioneer these shifting motifs, first designing prints for Watumull’s East India Store and eventually opening her own sportswear store, Hope writes. “Das converted them into locally appropriate designs,” he says. “Instead of Mt. Fuji, she used Diamond Head. Instead of cherry blossoms, she used ginger, plumeria, bird of paradise, hibiscus, anthurium.”

It would be remiss not to mention that the cultural rise of the aloha shirt was helped a great deal by bureaucrats and businessmen who really, really hated sweating. The city of Honolulu passed a resolution in 1946 that allowed civic employees to wear sport shirts from June through October. But that was just the first domino in making the aloha shirt acceptable business attire. In an effort to preserve and celebrate Hawaiian culture, the city also established Aloha Week in 1947, which soon expanded across the islands and swelled to a month. These festivals increased tourism and, subsequently, demand for aloha shirts.

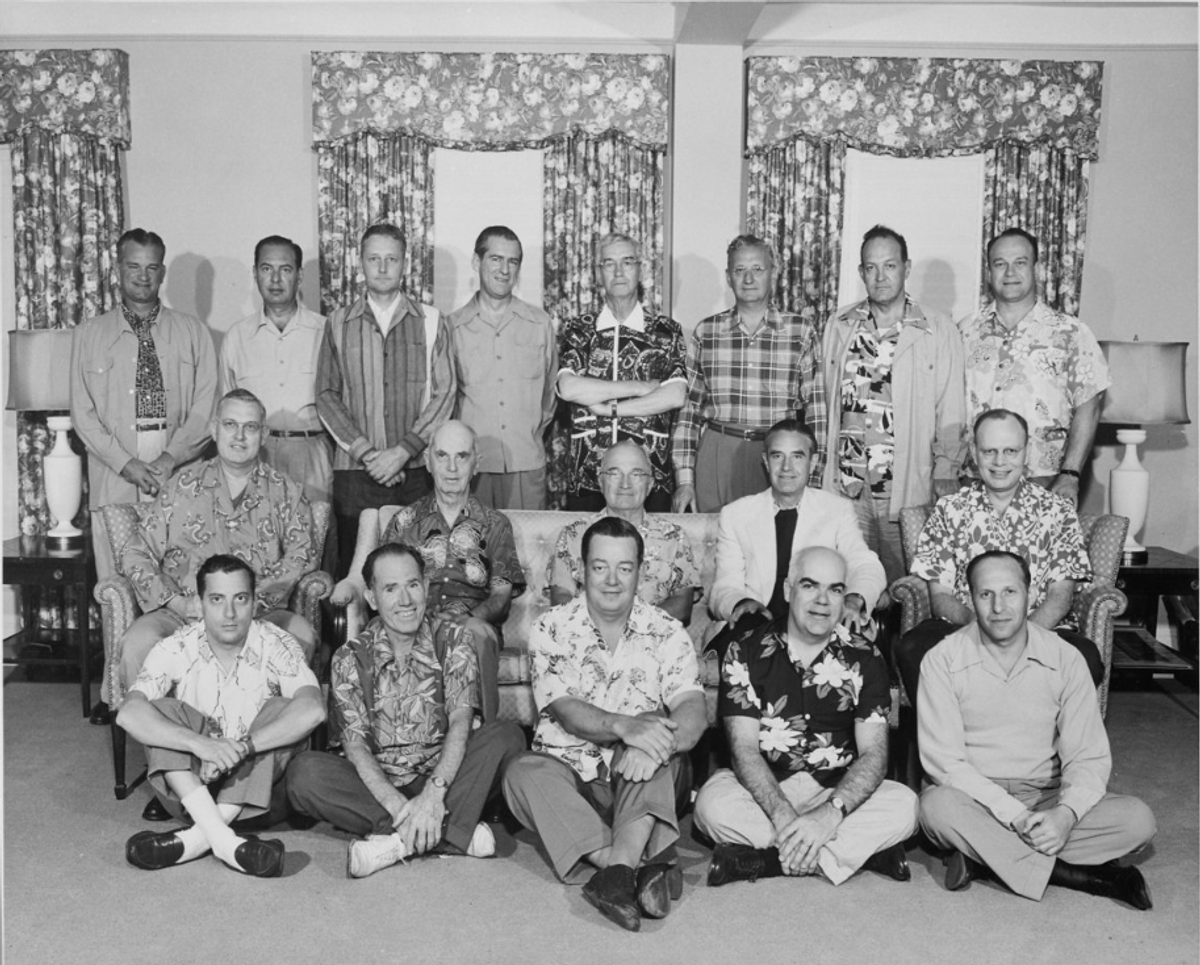

In 1962, a professional manufacturing association called the Hawaiian Fashion Guild launched the ambitiously named “Operation Liberation,” which sent two aloha shirts to every member of the Hawaiʻi House of Representatives and Senate, Hope writes. The Senate later passed a resolution recommending aloha attire be worn throughout the summer. Though there was initial outrage, relaxation won out. “I think most employers, bosses, and business owners thought that would be too casual and their customers wouldn’t treat them seriously,” Hope says. “But then they really embraced it.”

The guild later lobbied for “Aloha Friday,” a proposal asking employers to allow male workers to wear aloha shirts in particular on the last business day of the week during summer months. The tradition began in 1966 and morphed into what is now more widely known around the world as “Casual Friday.” In 2016, Democratic congressman Mark Takai asked House Speaker Paul Ryan to allow aloha shirts on Fridays in Congress, according to the Honolulu Civil Beat. Ryan declined.

Many of the iconic motifs of the shirts—hula girls, palm trees, outrigger canoes—aren’t exactly proper representations of the richness of Hawaiian culture. Perhaps the most authentically Hawaiian shirt is the palaka, a shirt printed with a distinctive woven pattern of blue and white checks, according to the paper “Some Notes on the Origin of Certain Hawaiian Shirts” Alfons J. Korn of the University of Hawaiʻi. Naturally, that has a history, too: The fabric was first imported for plantation workers at the turn of the 20th century.

On the other hand, many scholars see the aloha shirt as a symbol of Hawaiʻi’s putative multicultural harmony, according to cultural theorist Sämi Ludwig in American Multiculturalism in Context: Views From at Home and Abroad. And in her book The Art of the Aloha Shirt, textile historian Arthur wrote, “to those who live in Hawaii, it is a visible symbol of their multi-ethnic heritage,” made as it is with a Western shape, Japanese fabric, Chinese tailors, and Filipino style—and in Hawaiʻi. Hope agrees. “There’s a little feeling you have when you’re wearing an aloha shirt,” he says. “You have a skip in your step and a little smile. One guy said if everyone wore an aloha shirt there would be no wars, and I think it’s really true.”

Ludwig notes that some Native Hawaiians disagree. Haunani-Kay Trask, activist and former director of the Center for Hawaiian Studies at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, has condemned them as “the grotesque commercialization of everything Hawaiian.”

Now, some Hawaiian designers, such as Kūha‘o Zane of the company Sig Zane Designs, have reclaimed the aloha shirt with designs imbued with traditional Hawaiian themes. Zane’s shirts have become favorites of Hawaiian politicians, who are frequently seen wearing the sleek and subtle prints. “I feel that Haunani-Kay Trask’s opinion is directed toward companies that have borrowed the images and inspiration by the islands for their own profits without participating in reciprocity toward the community that created or make up the environment of the imagery,” Zane writes in an email. As a Hawaiian designer, Zane says he sees the aloha shirt as a platform to share his culture with a global audience.

Just as the aloha shirt may not have had a single inventor, it doesn’t represent any single idea, and can range from elegant and respectful to silly and incredibly tacky. It turns out that your aloha shirt could be saying more than you thought it did.

Our recommendation? What about this shirt, decorated with an image of one of the famous aloha shirts? It’s just so bad it might be good.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook