When the Cure for Poisonous Cider Was Hours of Bathtime

Doctors sent “Devonshire colic” patients to soak in the town of Bath.

In 1724, the English doctor John Huxham encountered a swath of patients suffering from stomach pain, cold sweats, and copious vomiting of blood-tinged, “exceeding Green bile,” often followed by painful paralysis. He immediately identified it as an outbreak of Devonshire colic, a disease that no longer exists but once proliferated in the English county of Devon.

The colic was unusual in that doctors knew what caused it nearly from the start. In the first written record of the disease, a doctor named William Musgrave wrote in 1703 that the cause was “rough and acid cyder, drunk in too great quantities.” Devonshire, after all, remains to this day a prime apple-growing and cider-making area.

Musgrave had identified the cause. Devon’s cider was indeed the source of the disease. But he had misidentified the reason. The roughness and acidity of the cider had nothing to do with it. The nauseous taste in the mouth, frequent vomiting, agonizing stomach pains, bright-red urine, pallid complexion, and fever he described are exactly the symptoms of lead poisoning, which, in later stages, can lead to severe paralysis and even death.

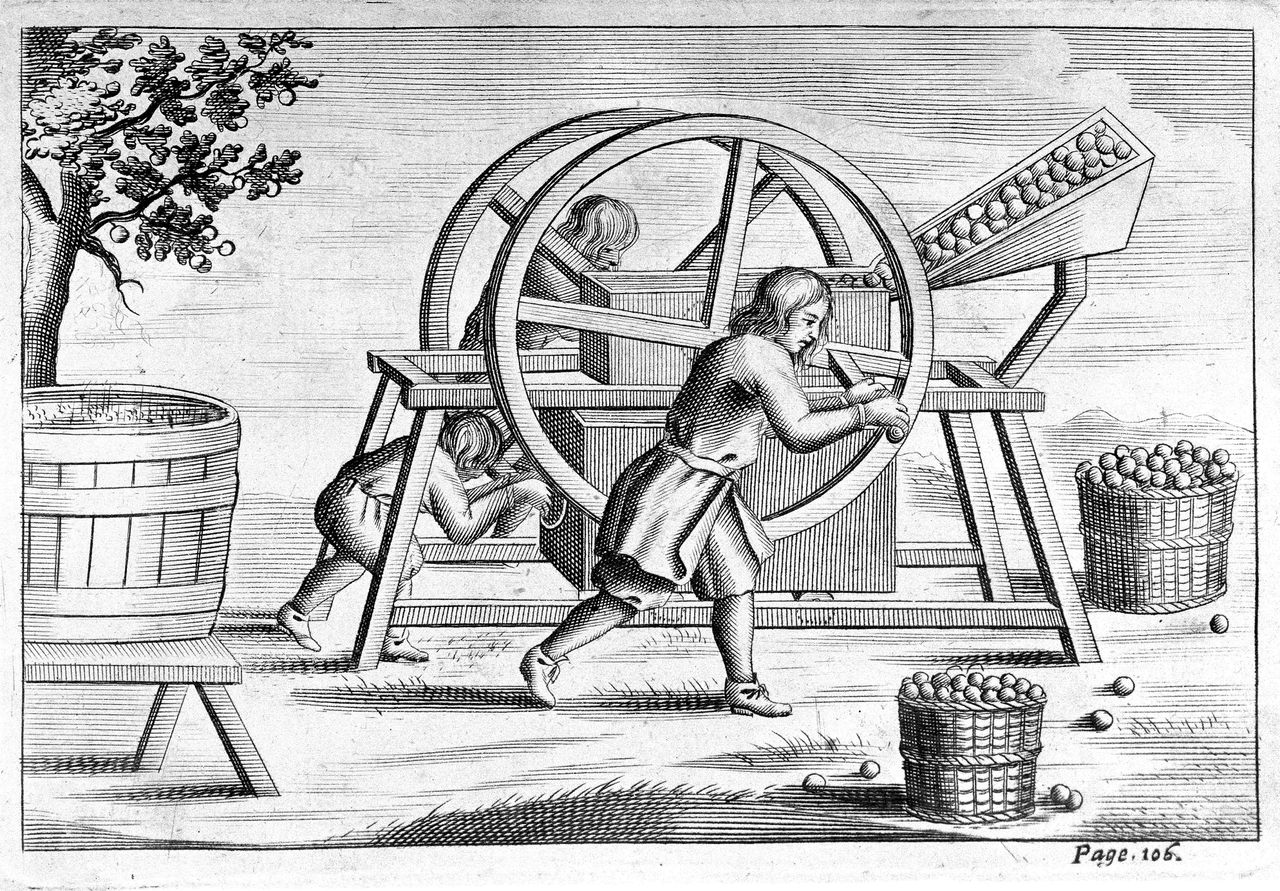

Since Roman times, lead had often made its way into alcohol, whether due to its makers using lead acetate to sweeten wine or storing it in containers glazed with lead. After centuries of neglect, writes doctor and medical historian H. A. Waldron, Devon’s orchards had been revived. And in Devon, cidermakers tended to process apples in lead-lined pounds and presses. Huxham blamed their flourishing for the 1724 epidemic. That year, he wrote, Devonshire produced more apples “than was known in the Memory of Man,” and the poor lived entirely off cider and apples.

Physicians of the time were familiar with lead poisoning, but it took several decades for another doctor, George Baker, to diagnose the true cause of the Devonshire colic. Skeptical of the acidity explanation, he pointed, in 1767, to the similarity of the symptoms between lead poisoning and the colic. In a series of experiments, he compared the lead content of Devonshire cider (high) to Hereford cider (none).

Well before Baker’s discovery, though, doctors who diagnosed patients with the Devonshire colic had to figure out how to treat it. Many of them sent the afflicted to the ancient town of Bath in the Avon Valley. The town’s name refers to the local springs, where mineral water burbles out of the ground at 120°F. Visitors flocked to the area to bathe in elaborate pools of healing waters, seeking cures for everything from leprosy to infertility.

While hot springs are undeniably relaxing, for the most part, that’s all they are. As Audrey Heywood wrote in a 1990 edition of the Medical History journal, “It is commonly assumed that spa therapy has only a placebo effect; that the pleasurable activity of immersion in warm mineral water has social and psychological effects, but no physiological value.”

Yet, as it happens, taking a long dip did have a marked effect on one ailment, Heywood wrote: “the paralysis that occurs as the result of chronic lead intoxication.” Even in the Middle Ages, physicians knew that sitting in the waters of Bath could occasionally cure some types of paralysis. The water’s reputation for curing the malady became so notable that the town proudly displayed a collection of discarded crutches. One victim, a reverend from Lincolnshire, came to Bath in 1666 unable to lift his arms. After bathing in Bath’s waters every day for almost two months, his doctor noted that the reverend was able to doff his hat in greeting once more.

The explanation for the cure is disarmingly simple. After consuming lead, the human body mistakes it for calcium and uses it to build bone. Over time, the accumulated poison causes violent symptoms. Weightlessness, as it happens, increases calcium loss from bones (a hazard for astronauts). Floating for hours gradually strips both calcium and lead from the skeleton, which is then urinated away.

Those “taking the waters” followed a certain system. Patients trooped into the pools in the morning, as early as 5 a.m. (The water was cleanest in the morning.) The King’s and Queen’s Baths were often filled with invalids, and the nearby Pump Room doled out glasses of warm, mineral-rich water. Other baths included the glamorous Cross Bath and the straightforwardly named Hot Bath and Leper’s Bath. Bathers submerged up to their necks, layered in thick clothing for modesty (for many years, the baths were mixed-gender). To amuse bored bathers, Heywood writes, musicians played instruments and sang.

Even as people drank more and more cider throughout England, Bath grew in popularity. By the early-18th century, it was de rigueur for the fashionable elite make the trip to Bath, not only to seek healing for high-end illnesses such as gout, but also to enjoy the pleasures of a resort town, which consisted of “dances, balls, gambling sessions, concerts, and theatrical performances in the evening,” writes academic Ian C. Bradley.

At the same time, doctors at the Bath General Hospital were conducting the “trial of the waters.” In what Heywood considers one of the first long-term medical therapy trials in history, doctors at the hospital treated poor paralysis victims with a regimen of fresh food and daily soaks. Those afflicted with paralysis from lead intoxication often recovered, not only from the weightless treatment, but from drinking large amounts of Bath spa water, which was rich in calcium and iron. It couldn’t have been very pleasant, though, to drink pints of the warm, sulfuric, eggy-flavored liquid.

When Baker published his findings, he knew both the treatment and cause of the Devonshire colic, and he felt sure they would be widely accepted. He was “well aware that it might cause some ill-feeling amongst the cider manufacturers,” Waldron writes. Yet, having only recently campaigned to repeal a tax on cider, “the Devonians were in a fighting mood.” Locals argued that Devon’s cider didn’t contain that much lead, and many cited the earlier theory that acidity was to blame. The lead Baker found in the cider, some even suggested, was caused by farmers shooting at birds in their orchards, which left bullets behind inside the apples.

Yet Baker’s thesis went relatively unscathed. It helped that lead-lined machines were slowly replaced by more modern ones, so by the end of the century, cases of the Devonshire colic became rare. After hearing about its deleterious effects, cidermakers may have quietly removed the lead from their presses, writes the doctor and medical historian R.M.S. McConaghey. “Had Baker achieved his object and eliminated the cider colic from the land of his birth?” muses McConaghey. “We do not know.”

Today, sipping a Devon cider and taking the waters at Bath aren’t hazardous or healing, respectively. But if you feel like it, you can still sip a cup of the the famous Bath water in the Pump Room to the sound of musicians playing, much as they did hundreds of years ago.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook