Bringing Life Back to a Massive Miniature of Hollywood’s Heyday

This model city is ready for its close-up.

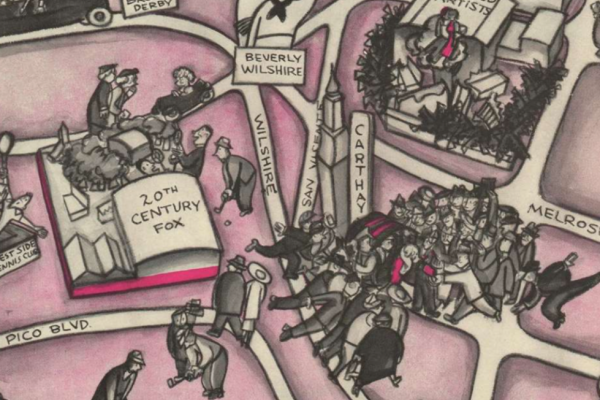

The hills glow soft and gold, as though flecked with a thousand fireflies. Hollywood Boulevard is lit up by street lamps and blazing marquees, but all is quiet. Cars fling little cones of watery light in front of them, or sit silently near the curb.

The scene is familiar to anyone who has strolled Hollywood’s famous streets. But this one is a little uncanny. Windshields are covered by a blanket of dust. Palm trees, too, and the tiny figures in front of the gates of the Paramount Studio lot. Outside of the Warner Theatre, a cobweb arches over the street.

The streets are small enough to fit atop a cluster of tables that are together the size of a cramped studio apartment. The miniature cityscape depicts the neighborhood—the same neighborhood where it can now be found—as it appeared in the late 1930s, and slowly, surely, carefully, Donna Williams—a conservator who specializes in sculpture and architectural materials—is now cleaning each light, each car, and each building, iconic and otherwise.

In total, the diorama squeezes 450 scale buildings onto an accurate street grid measuring 11 feet by 12 feet. It was fashioned in the 1930s by Joe Pellkofer, a cabinetmaker, and his craftsmen, during periods when jobs were lean. This model once had five cousins that extended its boundaries, to include a model of the famous Brown Derby restaurant and the beach at Malibu, complete with crashing waves that moved with little steel rods. Pellkofer said that the models together cost $250,000 to build, and that a 25-person team labored over them for four years.

Once complete, the model hit the road—to Atlantic City, among other places. The touring life was hard on the miniature metropolis. Some buildings got smashed along the way, and others were stolen outright. So it was time to take the model home, where it languished in Pellkofer’s Pasadena barn for decades.

It returned to Los Angeles by the mid-1980s, when it was on view at an Art Deco–inspired soda fountain. Celebrities had asked about the model over the years, Pellkofer told the Los Angeles Times in 1986, but he was neither starstruck nor especially interested in what they had to say. “I didn’t build the damned thing to see a movie star,” he told the paper. “I built it just because I felt like it. And because Hollywood is Hollywood. It’s magic.”

In the mid-1980s, once the model made it back home, according to the Times, Pellkofer’s grandson, John Accornero, reached out to Hollywood Heritage, a museum and preservation organization, to see if it could give the dioramas a permanent space. The organization’s co-founder, Marian Gibbons, told the Times she was “kind of speechless” when she first saw the landscape. “They said ‘miniatures,’” Gibbons recalled to the paper. “I didn’t expect it to be 12 feet.”

Today, as cleaning, conservation, and restoration progress, the model lives in Hollywood Heritage’s storefront annex on Hollywood Boulevard. (While the annex isn’t typically open to the public, visitors can stop in as part of a periodic walking tour of the wonders of old Hollywood.) The pop-up space is just steps away from the vacant, brick-and-mortar Warner Theatre, the 2,700-seat venue and headquarters of the Warner Brothers’ radio station, KFWB, which changed hands multiple times before sustaining damage during an earthquake and construction projects. It was shuttered in the mid-1990s. There, the conservator Williams, who is a member of the museum’s board, has been chipping away at the clean-up effort since the spring of 2018.

Though the model received some “clumsy” or “heavy-handed” repairs over the decades, she says, “There’s nothing shoddy in the way it was made.” Hollywood was chock full of craftspeople—set-makers in particular—with a knack for verisimilitude, and many details are spot-on. The ground outside the Chinese Theatre, for instance, is speckled with itty bitty handprints. Across the model, “Everything was handmade; nothing was purchased from a train-model shop,” Williams says. The original craftspeople added details, such as golden beams from the cars’ headlights and taillights, that only emerge under black light; electric lights were added later. Williams wonders if Hollywood set-makers moonlighted as model-builders, too, because some of the roofs made from scored wood, designed to mimic ceramic tiles, are extremely convincing. “Someone had to go in, take a thin layer of wood and score and cut it in such a way that it creates a corrugated look,” she says. “That’s not easy to do in a clean, precise way.” The reflections painted onto the buildings’ windows, she adds, display a keen sensitivity to light and color.

However careful they were with the details, the model-makers took some liberties with the big picture. “While the boulevards are in the places they should be, [some of the] buildings are not,” Williams says. A few iconic structures are a few blocks away from their actual locations, and others are omitted entirely. It’s not clear exactly why.

Williams’s first task has been to inventory the whole model, photographing and documenting places where things are broken or missing. Though the shrunken city wears its age gracefully, some of the buildings are missing the signs that once identified them, leaving nothing but time-worn glue dots to mark their absence. Getting the lay of the the land, Williams says, is “a little like assembling a 3-D puzzle.”

Cleaning begins by vacuuming the model with a nozzle the width of a dime, while using a dry brush to cough up little clouds of dust. Next, Williams wraps cotton around a skewer to make a swab, and spot-cleans stubborn areas.

Work is slow, partly because the task is considerable—the model is large and intricate by sculptural standards—and partly because Williams only has two hands and juggles many other projects. Hollywood Heritage is largely propelled by volunteers like her. “If I could get two or four conservation interns for three months,” she says, “we could be way ahead.”

The most finicky fix will likely be reviving a miniature version of one of the two steel towers that perch atop the Warner Theatre (more recently called the Hollywood Pacific Theatre). “One is in perfect condition, and the other looks like it was squashed and somewhat torqued,” Williams says. Maneuvering the thin wire they are made of is tricky. “If you try to move it at a point where it’s been creased, it wants to snap,” she says. It’s also hard to repair plastic signs. Conservation standards for newer materials like plastics are still emerging, and these old examples are prone to shattering.

Even as the diminutive buildings are dusted and patched up, some of their life-size counterparts face an uncertain future. It’s been like that for years. By the time a 12-block stretch of Hollywood Boulevard was added to the National Register of Historic Places in the mid-1980s, the old, glamorous buildings had been vanishing. The listing was a tactic to “intervene and draw attention,” says Adrian Scott Fine, director of advocacy at the LA Conservancy. “They knew that it was a special place, but had already lost a lot.” At the time, the Warner Theatre was one of buildings singled out for its charm.

The theaters flanking Hollywood Boulevard—whether long-gone or hanging on—are notoriously grand, flamboyant, and a little kooky. The Egyptian Theatre, which opened at the height of American Egyptomania, just weeks before Howard Carter cracked open King Tut’s tomb, is made of sand-colored blocks that evoke the pyramids and are adorned with hieroglyphs. The Warner was Hollywood’s answer to the trend of atmospheric theaters, which are festooned with clouds and stars to conjure a sense of being outdoors. The Warner didn’t go all in, but featured curtains and arches with elaborate scenes of greenery and fauna. “The programmatic architecture of the Chinese and the Egyptian, as well as the ornate Warner Theater [sic], Pantages, Palace, Hollywood, El Capitan, Iris, and others, created an aura of fantasy for the population of the area—and satisfied the tourists in search of ‘Hollywood’ as well,” wrote Christy Johnson McAvoy, from Hollywood Heritage, in the nomination form submitted to the National Park Service.

This tension over preservation is in the news once again, as the city council is expected to adopt a new community plan in 2019. This document will lay out a blueprint for future development and preservation, and Fine says it doesn’t go far enough. “It’s not as strong as we’d like to see yet,” he says. “We want to press a preservation-based solution, not demolition of any kind.”

Where it’s feasible, the Conservancy pushes for theaters to return to their original use. If that’s not possible, the organization encourages developers to retain and showcase features that contribute to the historic character. And in some of those cases, the Conservancy nudges developers to commit to make only reversible changes, so the potentiality for a cinema palace remains. One recent precedent is the Tower Theatre, which—under the close watch of preservationists—released detailed plans in August 2018 for an eventual reopening as an Apple Store* that highlights original architectural details.

The miniature version of the Warner Theatre will be mended by Williams, eventually, but the real thing, just outside, is stuck in its own kind of limbo. It’s empty, its marquee dimmed, its fate unknown. The decades-old miniature, so close to being lost, may outlive its inspiration.

*Correction: This post originally stated that the Apple Store had opened in the Tower Theatre in August 2018, and has been updated.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook