Untangling the Secrets of One of Harvard’s Historic Hair Collections

The university’s Houghton Library is home to a number of famous tresses.

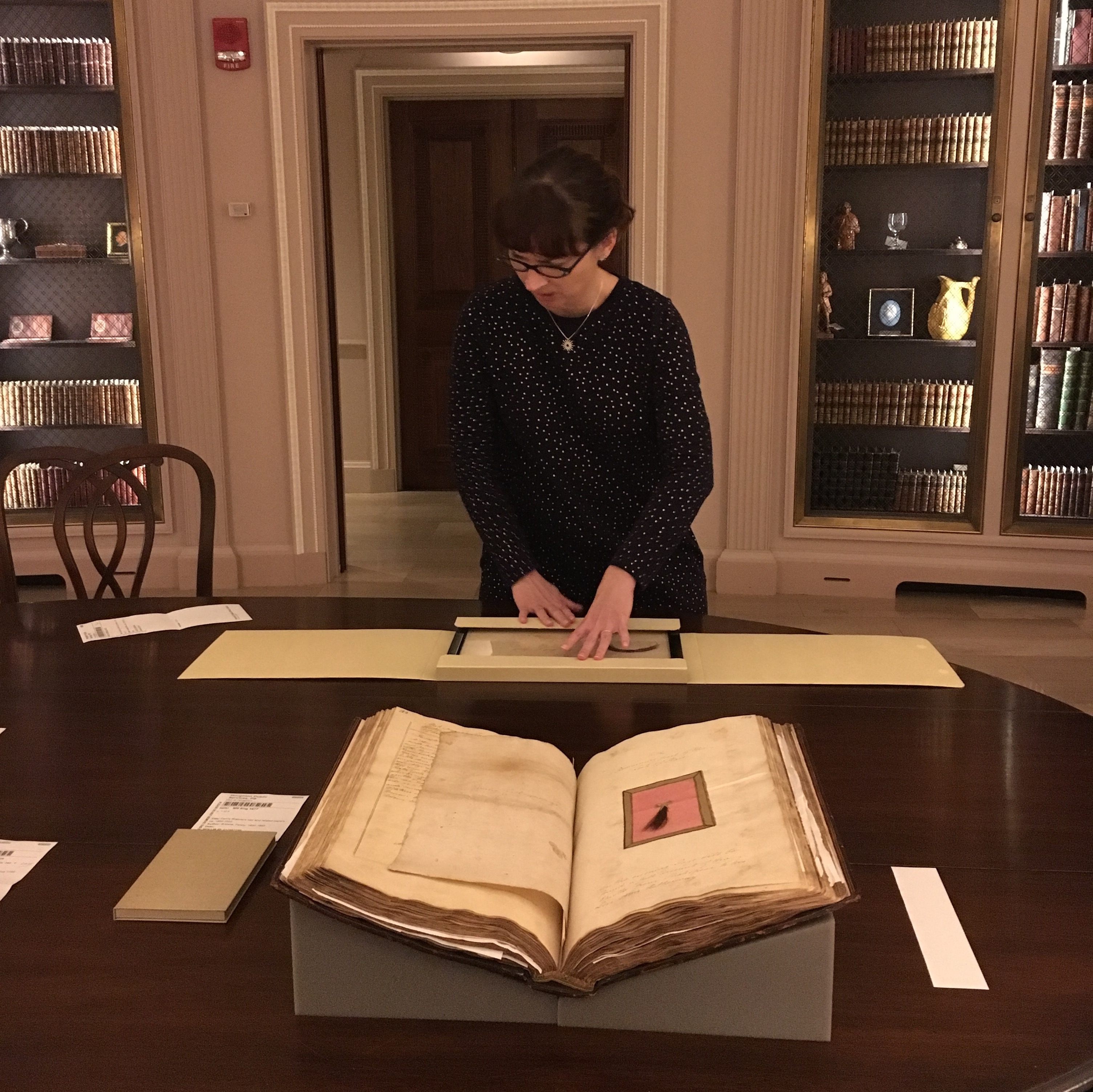

I’m in the Hyde Room of Harvard’s Houghton Library, and I’m biting my nails. Leslie Morris, the curator of modern books and manuscripts, and Carie McGinnis, the preservation librarian, are doing their darndest to pry open a two-hundred-year-old locket. They take turns, passing it between their gloved hands, bringing it under a lamp to get a better look at the clasp. Eventually, they give up, fearing they’ll break it. Morris turns to me: “You’ll just have to imagine that there are two little hairs in here,” she says.

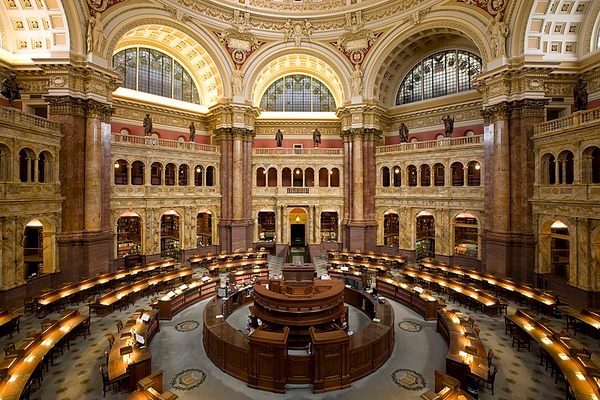

Houghton Library, a stately brick building in the southeast corner of Harvard’s campus, is where the university keeps many of its oldest and rarest books and manuscripts. The collections have a little of everything: there’s a roughly 2,000-year-old poem written on papyrus, a playbill for the Ford’s Theatre production during which President Lincoln was assassinated, and a sheaf of private letters Marcel Proust wrote to his lover, Reynaldo Hahn.

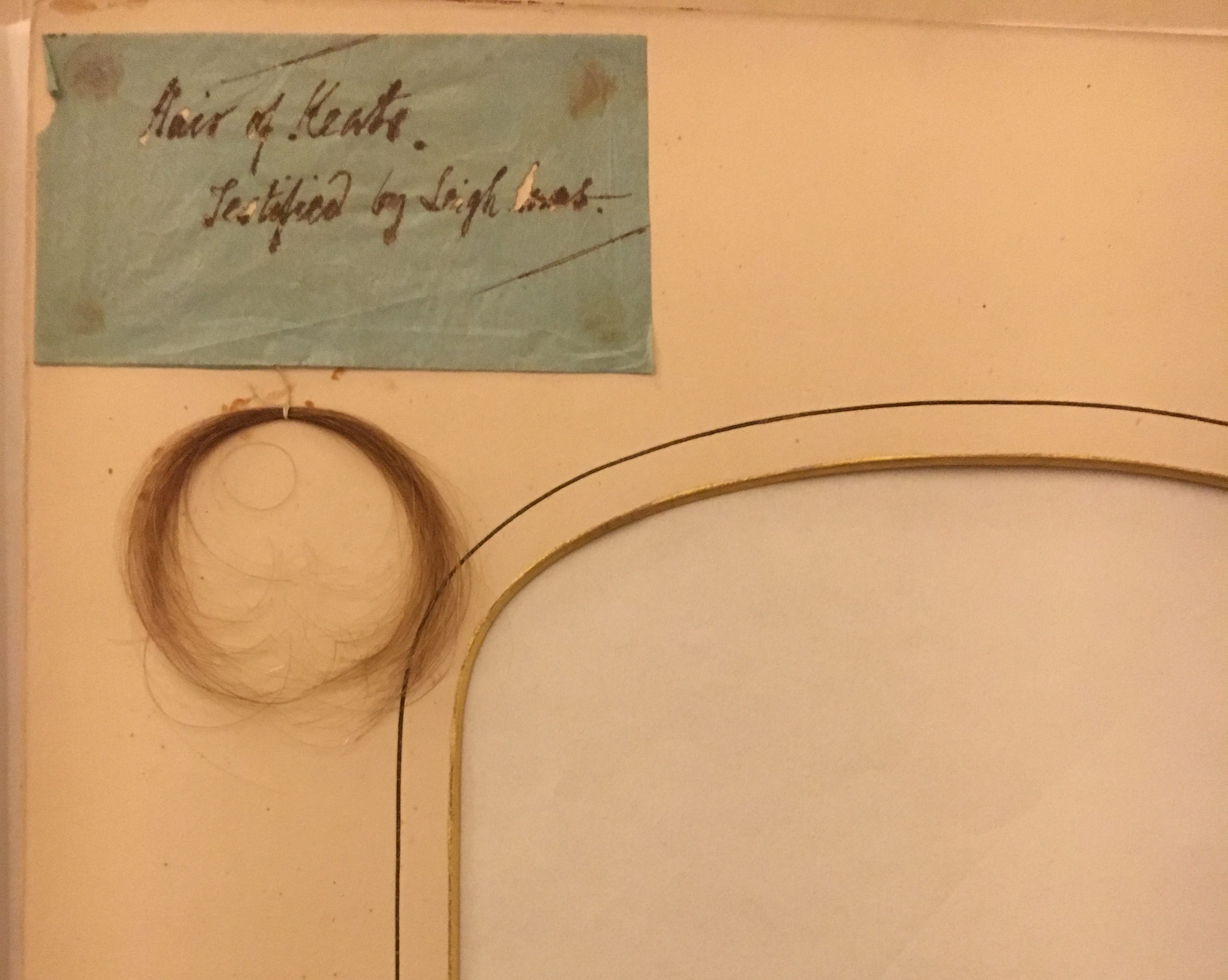

I’m not here to see any of this, though. I’m here for the famous hair. Houghton has a lot of it—specimens attributed to everyone from Napoleon I to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow—and McGinnis and Morris have kindly laid out a small selection for me. The two strands stuck in the locket, and which I have now been tasked with imagining, came from the head of John Keats. Luckily, there’s another sample of his—a light-brown whorl appended to the corner of an empty cardboard frame—nearby on the table, as well as one from his fiancé and muse, Fanny Brawne.

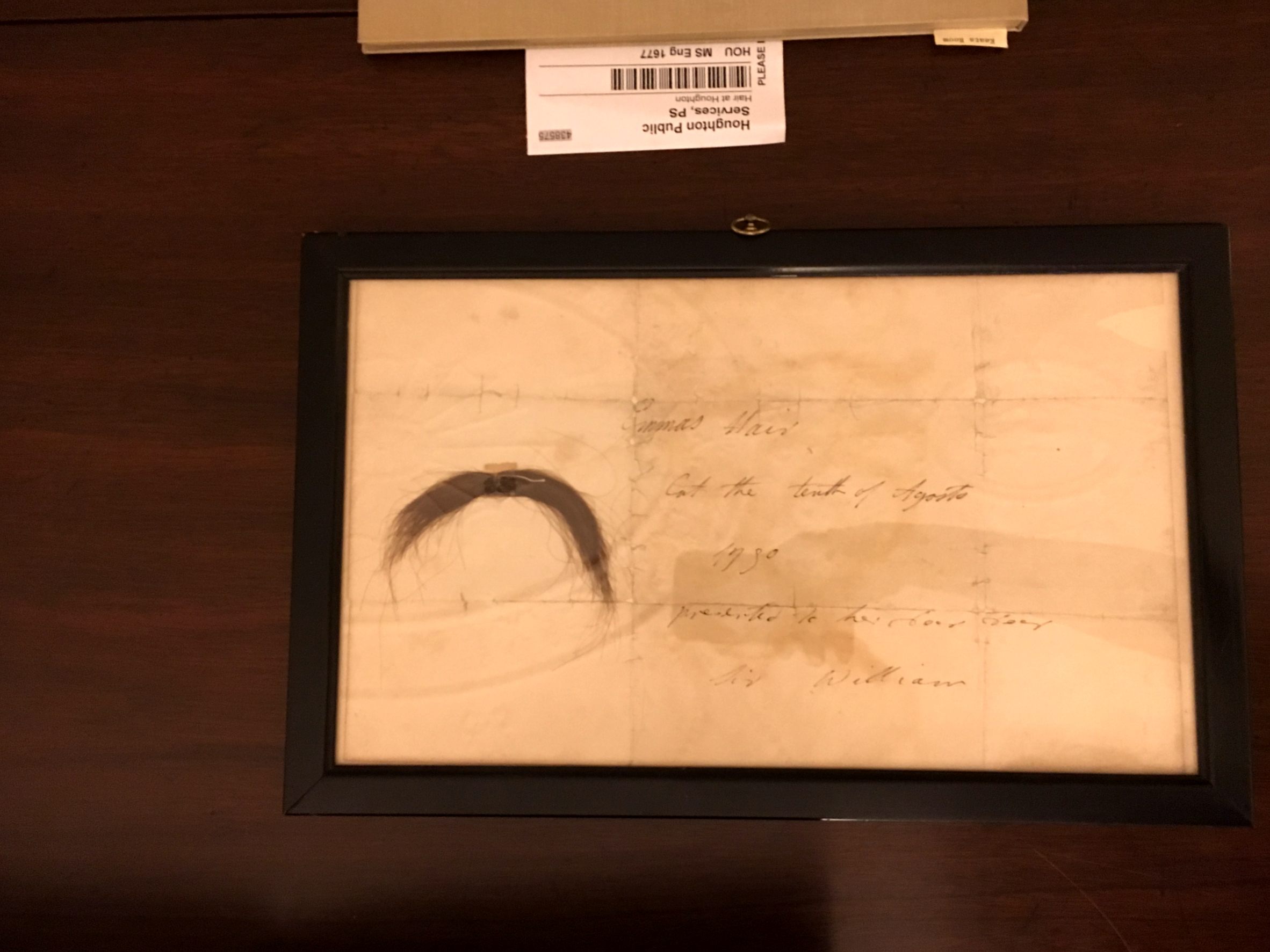

The open page of a large book showcases a brunette tuft of hair that purports to be, but is definitely not, Shakespeare’s (more on that later). A lock that once belonged to the famed actress Lady Emma Hamilton is taped to a piece of paper, and looks a bit like a mustache. And finally, there’s another locket—this one much easier to open—containing specimens from Betsy Fay and Joel Norcross, Emily Dickinson’s maternal grandparents.

Hair-swapping may seem a bit strange now, in an age where we can carry basically all of the non-forensic evidence of a relationship—from photos to correspondence to shared transactions—around in our phones. But in the past, and particularly in the Victorian era, swapping hair served as a common sign of affection, a way to literally give a friend, relative, or lover a piece of yourself, and keep a piece of them in turn.

Take, for example, Lady Emma Hamilton’s hair. According to the attached note, Hamilton cut off a lock on August 10, 1790, and gave it to “her dear dear Sir William,” whom she would marry a year later. “She probably presented her hair folded up in the note,” says Morris. Although both are now protected by a glass frame, you can tell that, once upon a time, the paper was folded and unfolded over and over again.

Saving hair could also serve as a way to keep the memory of a loved one close after their death or separation. “It’s a talismanic thing,” explains Morris. After Queen Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert, died in 1861, she sparked a mourning-jewelry trend by wearing his hair in a locket. In Anne of Green Gables, Anne asks her best friend, Diana, to give her “a lock of thy jet-black tresses” after they are forbidden from playing together, and therefore parted (they think) forever. “I’m going to sew it up in a little bag and wear it around my neck all my life,” Anne says.

When Emily Dickinson’s mother, Emily Norcross Dickinson, wore a round locket with her parents’ hair braided together inside of it, she was also participating in this tradition. One can imagine her lifting the locket and opening it to examine the two twists, one red and one gray.

Once it has been trimmed and saved, hair might take any of several paths to the stacks. Some acquisitions are deliberate. A scrapbook of tresses compiled by the poet and critic Leigh Hunt now belongs to the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin. The “Hair Book,” which features samples from Wordsworth and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, has become “one of the [library’s] most popular ‘show and tell’ items.”

Other paths are more roundabout. Oftentimes, a library will acquire an entire collection of papers or correspondence, only to find some spare hair squirreled away within it. When the New York Public Library received Charlotte Brontë’s traveling desk, a lock of her hair came along. Another Harvard library, Schlesinger, boasts some of Amelia Earhart’s baby hair, part of a larger collection of the aviator’s papers.

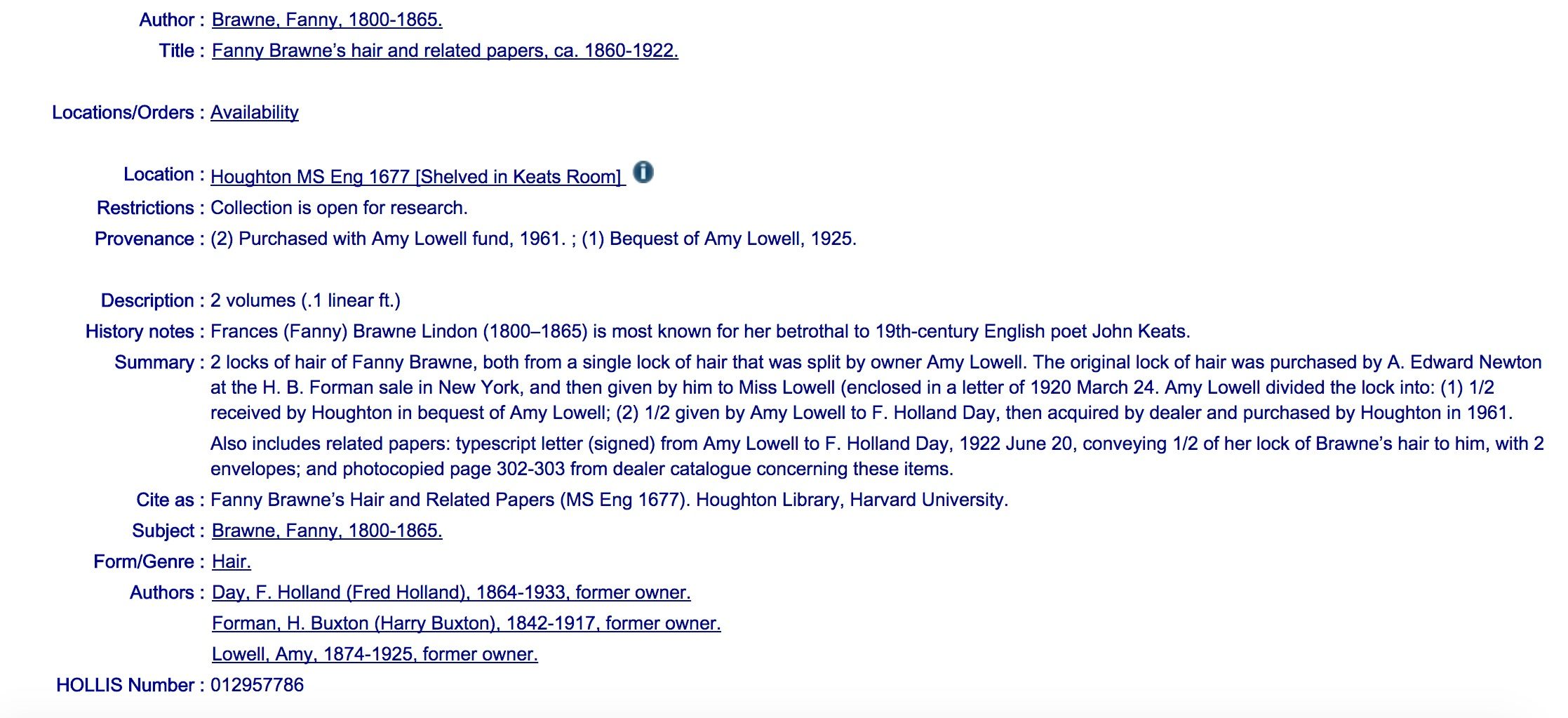

Similarly, much of Houghton’s hair collection was either given to the library, or hitchhiked in with other materials. “[Houghton] would not go out and purchase a lock of hair, because its research value is minimal,” says Morris. Half of the specimen from Fanny Brawne, for example, first came to Houghton through the bequest of the poet and collector Amy Lowell. (They did eventually buy the other half.) It’s now housed within a few layers of tissue paper and hidden inside of a false book, and looking at it doesn’t tell you much besides its color, a light brown.

In addition, Morris explains, “[hair’s] provenance is often suspect.” Take that supposedly Shakespearean sample, which has been mounted lovingly in a hand-drawn frame, and captioned in such a way as to suggest that the Bard gave it to his wife, Anne Hathaway. In reality, the book and the hair were both props in an audacious plot by a young man named William Henry Ireland. Ireland’s father loved Shakespeare, and beginning in 1794, Morris explains, the younger Ireland “decided to please his father by forging some Shakespeare manuscripts.” This fakery got more and more elaborate, until it included Shakespearean “self-portraits,” public performances of a “lost” play and, yes, a phony lock of hair.

After Ireland was unmasked, his own work became collectible, which is why Houghton has some of it. So did the hair, like Ireland’s other forgeries, come from his own head instead? “Who knows!” Morris says. Figuring that out for sure—or corroborating the sourcing for some of the other samples—would require DNA analysis, or a similar forensic intervention. “It would be a destructive test, so it’s not one we would undertake lightly,” says McGinnis. “And you’d have to have a point of comparison, which would be hard to get.” “You’d have to go to Rome and dig up Keats,” adds Morris.

The library has not received any hair donations during Morris’s 25-year tenure. If someone wanted to break this streak with a follicular gift, she says, “I would think very carefully about accepting it.” But, she adds, “once we’ve been given something, it’s our responsibility to hold onto it.” Houghton takes good care of their collection, ensuring each hair sample is stored in some sort of protective enclosure, and keeping it within set ranges of temperature (68-70 degrees) and humidity (45-50 percent). “If it’s a humid day, think of how your hair reacts,” says McGinnis. “Same with when it gets dry in the winter.”

In fact, human hair is so sensitive to dampness that librarians once used a gadget called a hair hygrothermograph to measure humidity. As conditions around the instrument changed, a bundle of hair within it would expand or contract, pulling on an attached stylus and causing it to record a readout. Although most libraries now use digital sensors instead, “I find it interesting that there is also this utility to hair,” says McGinnis.

The hair held in Houghton isn’t measuring humidity, nor revealing the genetic secrets of its wearers. But it is doing a different kind of work. “We recognize the importance of hair from an emotional point of view,” says Morris. For this reason, the Dickinson locket is generally on display in Houghton’s Dickinson room, and the Keats locket (unopened) in the Keats room. Harvard students, researchers, and other interested parties can also ask to see hair specimens laid out in the reading room, although Morris says that—during her tenure at least—such requests have been rare.

Famous hair looks pretty ordinary, especially when it’s no longer attached to a head, and as I move from note to book to locket, no ghosts are conjured before me. But seeing each sample carefully displayed—often in the context in which it was originally saved—a particular sort of romance does emerge. Each individual lock itself is less powerful than the many relationships that brought it to where it is today. A chain that connects not only the hair’s giver and recipient, but the collectors, curators, preservationists, and visitors, ensures it remains both relevant and safe.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook