How a Kitten Video Can Transmit Secret Instructions to Criminals

An ancient form of information-hiding known as steganography has infiltrated the viral internet.

Imagine your computer is infected. The virus that has infiltrated your machine commands it to perform tasks and open applications that you would normally use–except you’re not there to run them. At the same time every day, it launches Twitter, then generates user handles and hunts through tweets. It searches and waits until, bingo—it finds a recently tweeted link that leads to a photo of a flower.

But, this is no ordinary photo. Laced into the Github image file’s long string of code are secret instructions that it needs to extract and upload information from your compromised computer to an internet cloud service set up by a hacker.

This is how the virus known as Hammertoss, purportedly created by a Russian government-supported group called APT29, obtained information from a few oblivious high-value companies. In early 2015, the United States cybersecurity company, FireEye, was able to follow the malware’s digital trail as it hopped between three websites: Twitter, GitHub, and internet cloud storage services. Hammertoss was able to hack into computers after it collected and pieced together instructions concealed in the guise of innocent pictures—an information-hiding technique known as steganography.

Today, criminals, hackers, terrorists and spies rely on these kinds of of information-hiding techniques. The more layers and steps it takes to send a secret message, the easier it is to shake security experts off the trail. These techniques are not limited to breaking into computers. A whole new form of communication is stewing in the depths of the internet, permitting people to send anything from a leaked Beyoncé song or a PDF of a banned book, to a file filled with child pornography and instructions to bomb a building, all hidden inside the files of innocuous-seeming photos, videos, or audio.

Secret information can easily be embedded into the code of seemingly innocent files. (Photo: Luis Llerena/Public Domain)

Steganography has been used for communication since long before computers or the Internet ever existed. The ancient Greek historian Herodotus documented the earliest known example of the information-hiding method in 440 BC, when a man carved an urgent war message onto a wooden tablet. He coated the tablet in wax so he could easily smuggle the unsuspecting item past enemy lines. Herodotus also described how Greek generals would tattoo messages on a slave’s scalp. When the slave reached their comrades, they would shave the regrown hair and read the next plan of attack.

The modern incarnation of this stealthy communication mechanism works along similar lines—a message piggybacking on digital carriers, or seemingly innocent data.

“If you don’t see it, and you don’t know whether something is hidden, you do not have any signs that something suspicious might be going on,” says Wojciech Mazurczyk, a computer scientist at the Warsaw University of Technology in Poland, who has been developing and researching digital information-hiding techniques for over 10 years.

Johannes Trithemius, a German abbot, invented the term “steganography” and wrote one of the earliest publications on secret information hiding, Steganographia written in in the late 1490s. This is a replication of a chart from the text by John Dee, a philosopher for Queen Elizabeth I. (Photo: National Library of Wales/Public Domain)

Johannes Trithemius, a German abbot, invented the term “steganography” and wrote one of the earliest publications on secret information hiding, Steganographia written in in the late 1490s. This is a replication of a chart from the text by John Dee, a philosopher for Queen Elizabeth I. (Photo: National Library of Wales/Public Domain)

Mazurczyk and his colleagues define steganography in the digital realm as a method of hiding and sending messages (both innocent and nefarious) in the long codes of digital files or in the sea of network data.

The array of file carriers and routes make it tricky for steganalysts—21st century hidden message detectives—to find these transactions. Mazurczyk and Berry are two detectives among a class of highly specialized computer scientists who have the important job of thinking like cybercriminals in order to catch their deviant messages. They build advanced steganography programs to understand how to track them down in the real digital world.

To put a stop to Hammertoss, Berry explained that they had to reverse engineer the malware, or unpack the code to figure out how it behaved. Viruses like Hammertoss are a concern because they take advantage of services that many use every day. “This is sort of like the cusp of sophistication—the best well thought out sample of malware. We view this as where malware is going, which is going to be difficult for organizations to detect this kind of activity.”

Some steganalysts create programs to solve crimes, while others create them to give internet users a means of privacy in an age when all your digital behavior is harnessed online. Meanwhile, criminals continue to sharpen their own information-hiding skills. While there are no tools out in the dark net as sophisticated as the programs developed by academics, cybersecurity specialists around the world continue to create these programs in order to learn how to detect and eliminate the threat of the next terror plot or dangerous computer and network virus.

This is another copy of a secret code from Steganographia by John Dee. (Photo: National Library of Wales/Public Domain)

This is another copy of a secret code from Steganographia by John Dee. (Photo: National Library of Wales/Public Domain)

To understand the future of secret digital communication methods, it helps to investigate its evolution. The modern steganography programs that Berry and Mazurczyk analyze are complex and layered. But the technique has evolved from its earlier, simpler roots, explains Jessica Fridrich, who teaches a graduate course on “Information Hiding and Detection Theory” at New York’s Binghamton University.

Steganography at various times in history has inspired everything from invisible inked letters to today’s Facebook and Twitter photos laced with encoded information. In the 1900s, the Webster Dictionary eliminated the word steganography because the writers claimed that is was synonymous with cryptography, where information is garbled unless you have the secret program to unlock the message.

Encrypted messages are seen and caught easily, but are extremely hard to decode, Fridrich explains. A steganographically hidden transaction is difficult to intercept, but if it is, the message is then easy to read. Cybercriminals and computer scientists often design programs, like Hammertoss, that implement both techniques, ensuring their message is safely hidden and difficult to crack.

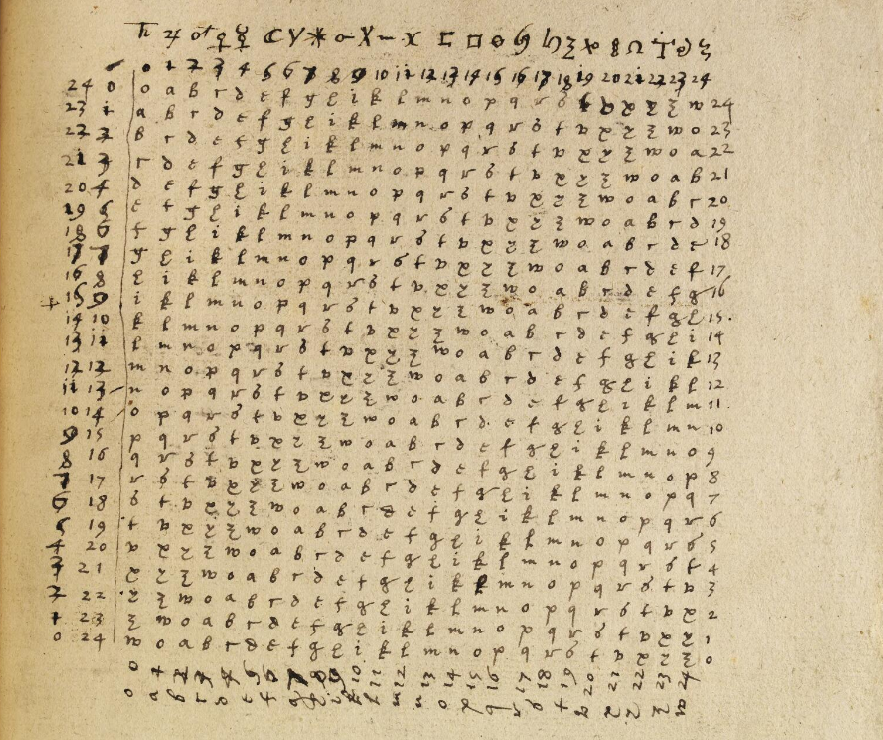

An NSA photo of microdots taped inside the label of an envelope sent by World War II German spies in Mexico City. Microdots are hidden messages, text or images, shrunk into inconspicuous, tiny dots. The message was intercepted by the Allies. (Photo: Public Domain)

An NSA photo of microdots taped inside the label of an envelope sent by World War II German spies in Mexico City. Microdots are hidden messages, text or images, shrunk into inconspicuous, tiny dots. The message was intercepted by the Allies. (Photo: Public Domain)Fridrich specializes in digital steganography—hiding information in static digital files like JPEGs and MP3s. This involves hiding a secret message by manipulating the least significant bits of numerical code in a static file such as an image or song. For example, in the television series Mr. Robot, the main character uses a real converter, DeepSound, to hide information in audio files. It doesn’t take much to smuggle a wealth of information—a six-minute MP3, for example, can secretly hold all of Shakespeare’s plays.

“One of the major properties of steganography systems is that it cannot be proved,” says Fridrich. If performed successfully, steganalysts can’t claim that a secret message was sent if it looks like it was never sent in the first place.

Coders can alter some of the color pixels in an image to hide secret information. (Photo: LLEELL/CC BY-SA 4.0)

Coders can alter some of the color pixels in an image to hide secret information. (Photo: LLEELL/CC BY-SA 4.0)

When the U.S. Air Force recruited her to work on information security applications in 1996, Fridrich joined one of the first investigative groups devoted to studying steganography. The technique was still under the radar, and little to nothing was known about how to detect these messages.

But figuring out how to place secret information inside other messages is not actually that challenging. “There is so much data and numerical values in a picture that it could become a good container for a message,” Fridrich says. “It became clear that if no one was doing it then, people will be doing it eventually.”

Computer scientists began noticing the first instances of digital steganography in the late 1990s, when a program called S-Tools was used to hide child pornography inside different digital files between 1998 to 2000. S-Tools can take bits of data–color pixels in an image for example–and replace them with the code of the pornography files. The perpetrator, who worked at a government facility, distributed the files through his email on his work computer, and was caught when investigators detected alterations unnoticeable to the eye in the color patterns of the GIF palette.

It was not until the events of 9/11 that people began paying closer attention to the way information was secretly exchanged online. One theory is that the terrorists utilized eBay auctions to share steganographically modified images with the plans to carry out the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, according to multiple articles in USA Today, and Gordon Thomas’s book Gideon’s Spies: The Secret History of the Mossad. It was never officially confirmed since the images couldn’t be found.

Mazurczyk believes this was because there were not any technologies at the time that could efficiently track down the secret messages. The events led U.S. foreign officials (and the world) to rethink what we see on the internet.

Soon, more cases of steganography began making headlines. The first big attacks in the cyber world was Operation Shady RAT in 2006. It targeted large institutions and industries around the world, leaving millions of dollars of damage in its wake. A Chinese group hid the Operation Shady RAT virus in innocent JPEG and HTML files and infected 72 organizations’ networks, including the United Nations, the U.S. Federal Government, research institutions and economic trade companies.

Now, researchers are finding out that secret transactions are even cloaked under messy, heavy flows of data—a method known as network steganography. Mazurczyk discovered that the crackles filling the quiet moments in a Skype call provide the perfect disguise to send longer, data-heavy files. During a Skype call, millions of bundles of voice data stream between users. Even in the seconds when neither party is speaking, data packets are still being sent, which creates the fuzzy noise that punctuates these digital conversations.

He and his colleagues, Maciej Karas and Krzysztof Szczypiorski, created the program SkyDe (the name a fusion of the words Skype and hide). It alters the data packets that flow between users, embedding a piece of a message or file inside those tiny moments of silence. The alterations to the data packets are so minute that they sound just like normal Skype static even to those with a sharp ear. Over the course of a single call, the sender can deliver up to 2,000 bits of camouflaged data per second—enough to transmit the 340 pages of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four in one hour. The receiving user collects all the pieces and uses software on his or her computer to read the entire message.

Voice data packets that flows between Skype callers can be alterred ever so slightly to carry secret bits of information. (Photo: Anchiy/shutterstock.com)

Voice data packets that flows between Skype callers can be alterred ever so slightly to carry secret bits of information. (Photo: Anchiy/shutterstock.com)But not all information-hiding tools are used to execute crimes. For hundreds of years, people have been using secret communication methods for principled purposes. In 1499 in Venice, Italy, Francesco Colonna devoted himself to the church. During his priesthood, he wrote Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, a romance set in a fantastical world. Historians believe that Colonna hid a confession to his secret love that could be deciphered from the first letters of each chapter of the story. The power of steganography provides those who are prohibited from speaking to each other a secret channel to safely communicate.

Its potential to help individuals in countries who are unable to access certain information or communicate with others is a more realistic possibility than using it to send malware, says Ian Goldberg, a privacy expert and researcher on the Cryptography, Security, and Privacy group at the University of Waterloo in Canada.

Goldberg works on steganography technologies that empower people to take control of their digital footprint and online privacy. He is one of the developers of the program Tor, which allows people to visit websites secretly by hiding the signal in another request. To a third party, it may look like you’re simply viewing videos of cooking recipes, but under the covers you are actually using a proxy to shield your true activity. Goldberg believes that this is the path steganography will take in the future. The majority of steganography practices that are being used today among the general public are completely innocent, according to Goldberg.

“I really don’t think its use for evil is really the concern,” he says. “These privacy protection techniques give more utility to the good guys who just want to protect themselves when they go online, versus the bad guys who already have a lot of ways to protect their communication.”

Mazurczyk agrees that there are opportunities for steganography programs to be helpful, but he advises that we should remain cautious. Inventions that were created with the purest of intentions can be manipulated and used for wrongdoing, too. “You can take a fork and stab someone in the eye or you can just put it in your dish,” he notes.

Pages from the romance Hyperotomachia Poliphili said to be written by Francesco Colonna and published around 1499. Scholars believe that he hid secret messages in the text to his lover. (Photo: Public Domain)

Pages from the romance Hyperotomachia Poliphili said to be written by Francesco Colonna and published around 1499. Scholars believe that he hid secret messages in the text to his lover. (Photo: Public Domain)It is inherently hard to find a message sprinkled in bits throughout the internet. And the sheer volume of steganography methods and carriers makes detection even more challenging, explains Mazurczyk. For instance, if an analyst has to detect 1,000 methods, all utilizing different kinds of file carriers (Facebook profile pictures, an audio book of Harry Potter, a video of puppy doing a somersault), then he or she would need 1,000 specific programs to detect and eliminate each individual method.

To find or eliminate a specific information-hiding method or suite of methods, analysts create a machine learning-based inference system—an algorithm which can be applied to different data sets. These can classify and convert letters and numbers in a steganographically altered file, like a picture for example, so the message no longer makes sense. But, if a cybercriminal adjusts one step in the delivery pathway, the counter measure that was just created becomes useless because the detection software was programmed to track down the one hiding method.

“That is why it’s so hard. There is no one product that can be plugged into the network that will solve the issue,” he says.

Security experts are reanalyzing the weak spots in existing services and devices that cause them to be vulnerable to covert communication. Mazurczyk and his colleagues are currently setting up a new initiative called Criminal Use of Information Hiding alongside Europol EC3, the European Cybercrime Center, that will link research institutions, academics, industry and law enforcement agencies in an effort to monitor the progression of malicious steganography applications. He hopes it will help prevent steganographic methods from inciting catastrophic events later on.

Computer scientist Wojciech Mazurczyk often jokes that his name contains a secret message that needs decoding. Here, he stands in front of the Europol EC3 building, the European Cybercrime Center. (Photo: Wojciech Mazurczyk)

Computer scientist Wojciech Mazurczyk often jokes that his name contains a secret message that needs decoding. Here, he stands in front of the Europol EC3 building, the European Cybercrime Center. (Photo: Wojciech Mazurczyk)The future of steganography looks a lot like a James Bond movie. We are all familiar with the scenes from spy movies that show an undercover agent placing an envelope with sensitive information under a park bench for his or her accomplice to come pick up. The modern scenario, Mazurczyk says, can involve two spies who hack into the sensors and controllers in an airport’s network, embedding secret data. “Then, while traveling, one spy sends the message during a morning flight and the other spy reads it during an evening flight,” says Mazurczyk. “In my opinion, this is 21st century spying.”

Mazurczyk suggests network steganography could provide a much darker space for spies, hackers, and criminals to communicate in the future. A device, even when the user isn’t on it, will always be linked online, sending a steady stream of data packets to the network. And the more devices connected online, the more doors cybercriminals have to take over or steal from a system.

The options for nefarious digital information-hiding will also multiply, due to the rise of mobile malware. McAfee security group discovered 9.5 million new mobile malware threats in early 2016, which is about a 633-percent increase over the past three years. Smartphones are much less secure than computers because of the countless number of access points an attacker can infiltrate (image galleries, video, audio, Skype), but many users don’t realize they need virus protection software on their personal devices.

Some online security networks may be so vulnerable that attacks can be happening at any moment but go undetected for years. It took five years to detect Operation Shady RAT, the 2006 virus deployed by a Chinese hacking group, which accumulated over 300 million dollars in stolen intellectual property each year in the meantime. As Jessica Fridrich warns, “In a digital age, seeing is not believing.”

Information hiding techniques continue to become more sophisticated. (Photo: Mclek/shutterstock.com)

Information hiding techniques continue to become more sophisticated. (Photo: Mclek/shutterstock.com)This is the new state of digital affairs, where hidden battles and secret transactions ensue between endless lines of esoteric letters and values. Figuring out how to navigate this world will be integral in our future. Steganography will be a part of this landscape of covert communication, for good or bad. “Steganography will always have a place,” says Jordan Berry from FireEye. “It will probably always play a role in cybersecurity.”

Techniques for detecting and preventing steganographic activity will continue to develop, and with it new forms of hiding secret messages will evolve as cybercriminals try to find ways to get around those defenses; it is a never-ending cycle of both sides trying to outcompete the other. The next time you view a photo, listen to a song, or call a friend on Skype, you too many want to think twice about whether or not you are getting the full story.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook