How Glitch Fare Hunters Turn Airlines’ Tricks Against Them

Though still not for the faint of heart, ultra-cheap error fares are no longer just a niche obsession.

Why not just go? (Photo: Jay Mantri/CC0)

Dewey Cyr figured it would be years before she made it back to Barcelona. She loves the city—she spent a blissful semester there in college—but even a cheap flight from Boston costs a good $800 round-trip. For Cyr and her husband, both graduate students, such a voyage hardly seemed realistic.

But then, on February 29th, Cyr checked Facebook and saw, tucked among various updates and news articles and photos, an all-caps post shared by a friend. “ERROR FARE: NEW YORK TO MANY EUROPEAN CITIES FROM ONLY $252 RETURN,” it blared. After a few rounds of frantic clicking, Cyr, like hundreds of others that day, ended up with two tickets to Barcelona, at $282 each. She had potted the savvy traveler’s favorite new prey—an error fare.

Cyr vividly remembers the thrill of booking her Barcelona ticket. (As someone who tried and failed to nab the same deal, the moment is lodged in my memory, too). But when I mention it to Tarik Allag—the founder of Secret Flying, the site that surfaced the fare—it takes him a minute to recall that particular coup.”Oh, that was a big one!” he says as it snaps into place. “That was really good.”

It’s hard to blame him. Every day, Secret Flying tempts its hundreds of thousands of Facebook followers with dozens of cheap flights. Some are regular deals—discounts, flash sales, and other airline-approved promotions. Others, though, are error fares. These accidental glitches plunge prices down so low, they make you do a double-take: Portugal to Brazil for just 114 euros for a 10-hour, nearly 5,000-mile trip, for example, or Switzerland to Thailand for an insane €6.

For years, computer-savvy travelers have sniffed out these lucrative mistakes, sifting through airfare matrices for hours until they strike gold, and communicating with each other in code to keep airlines from following their trail. More recently, though, aggregators like Secret Flying have made it easier than ever to nab error fares. In the process, they’ve turned flight deal-seeking into a sport—and a dedicated community.

Allag got into the error fare game for a simple reason—he lives in London, and he hates rain. “The weather out here is terrible,” he says. “Any excuse to leave is good enough.” After about 18 months of seeking out deals for himself and his friends, he figured he’d level up: “I thought, why not just take a punt at it and provide cheap flights to the public?” he says. “I really didn’t expect it to be so successful so quickly.” Allag, who formerly worked in sports medicine, now runs the site full-time, aided by a team of employees stationed around the world.

Ticket-buying the old fashioned way, at Washington, D.C.’s municipal airport in 1941. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USF34-045002-D)

Back in the early days of air travel, many governments, including the U.S., regulated ticket prices. Customers would walk up to a flight desk or a travel agent, pay a predictable amount, and be on their way. Beginning in the late 1970s, though, pricing in the U.S. was deregulated, computers replaced telephone hubs, and everything started to get complicated. As with any system, the more moving pieces that get added—sub-charges that make up the total fares, intermediaries between the airline and the automatic and human systems tasked with managing all of it—the higher the probability that something will go wrong, and that the numbers that go in one end will come out differently on the other side.

Allag sorts error fares into three types. Some are plain old computer glitches, hiccups by airline websites, or by online travel agencies like Expedia or Kayak. Others are mistakes made by real live employees: “One of the biggest error fares we had was with United Airlines—first-class tickets from the U.K. to pretty much anywhere in the U.S. for $79, when it should have been over $4,000,” says Allag. “That was a human-error fare. They inputted the wrong currency conversion from Danish kroner to British pounds.”

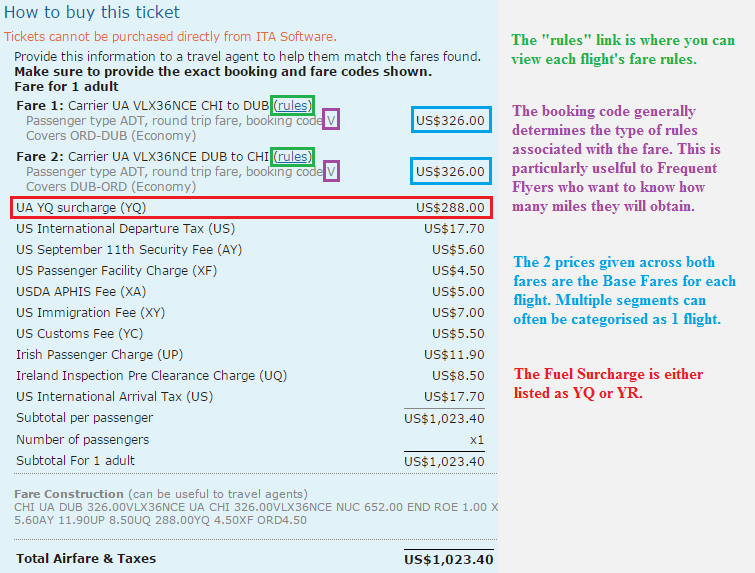

The third and most common species of error fare is known as a “fuel dump.” Although it shows up as a flat rate on your receipt, the price of an airline ticket is actually made up of three components: the base fare, taxes, and a so-called “fuel surcharge,” which varies widely from flight to flight (and, often, from day to day). “Because the fuel surcharge was implemented long after the reservation systems were created, they are prone to glitches,” says Allag.

With the right combination of flights, it’s possible to confuse the system sufficiently that part or all of the fuel surcharge simply falls off. If the base fare was low to begin with, you’re left with a great deal.

Fuel surcharges, as explained by Scott Mackenzie. (Image: TravelCodex)

Searching for fuel dumps manually is difficult and time-consuming, not to mention against airline policy. For years, it was largely the purview of a small community of devotees. These patient travelers tested combinations, kept track of slowly-emerging patterns, and shared their findings on forums other travel bloggers called ”the Wild West of the airline ticket world.”

Here, threads were headed up with blocky red warnings (“Do not call the airlines under any conditions!”). Fares were explained via code words, to thwart lurking employees—referencing “The 13-Miler” meant that adding a particular Caribbean leg would slough off a fuel surcharge, while “Pineapple Poke” indicated the same for a jump between Hawaiian islands. Secret fares were kept, in a word, secret. In 2010, a deal site called Airfarewatchdog shared a fuel dump, and was immediately confronted by what the site’s owner described as “a virtual mob with torches and pitchforks.”

Now, though, the former Wild West is opening up. “Many more sites—including mine—are writing about [fuel dumps] and exposing them to a new audience, even if they aren’t actually adding any new information to the conversation,” says Scott Mackenzie, who heads up the blog TravelCodex and has been hunting fuel dumps since 2010. When a lot of people jump on a deal, airlines quickly find out about it. If this happens enough times, they, too, can find patterns, and fix glitches that might have otherwise led to future mistakes. As a result, Mackenzie says, “fuel dumps are much less common than they used to be.”

The deals that remain, though, reach far more people. Allag—who generally sticks to less dicey strategies, though he has created a fuel dump tool ”for educational purposes only”—considers this a net gain that transcends the monetary. “On first glance, people think we’re just saving people money, but it’s not really that,” he says. “It’s more about helping people shape their travels.”

Where ordinary travel requires meticulous saving and detailed planning, traveling by error fare rewards spontaneity, and a willingness to head to less obvious destinations. A certain overall flexibility is also required—airlines can, and do, cancel tickets purchased through error fares. As Allag puts it, “It’s not for everyone.”This week alone, error fares popped up that—if they’re honored—could send Europeans to Chile, Floridians to Pakistan, and New Yorkers to Zurich. “It’s just a lovely feeling,” he says.

Those on the other side generally agree, as is evidenced by the comments they leave on posted deals (the site also gets a lot of fan mail, Allag says.) Some people are so enamored with this system, they’re essentially letting error fares plan their vacations—Cyr, for example, is headed to Norway next January, thanks to another well-timed post.

Even those who can’t leave on a dime can, in some ways, benefit from this philosophy. After my failure to book a ticket to Europe, I pinned Secret Flying to the top of my Facebook newsfeed. When I sign on to see what’s happening in my small world, their posts—which tend to combine sunny photos with enthusiastic diction (“GO! GO! GO!”)— remind me of what’s out there, and that it might be easier to get to than I thought.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook