How Green Bay, Wisconsin Became the Toilet Paper Capital of the World

(Photo: Natalia Dobryanskaya/shutterstock.com)

(Photo: Natalia Dobryanskaya/shutterstock.com)

No city deals with more assholes on a daily basis than Green Bay, Wisconsin.

This is not a metaphorical statement: Green Bay is the toilet paper capital of the world. But how did Green Bay become the Keister Kingdom, the Crapital City, the Xanadu of Doo-Doo? It was largely thanks to a revolutionary invention that changed bottom wiping from painful penance to inconsequential chore, and elevated this small mid-western city into the number one of number twos.

Wiping itself has a long and storied history. Chimpanzees have been observed using leaves and twigs to wipe feces from their buttocks. Humans have embraced a wider array of tools for this unpleasant task. Grass, fur, shells, stones, corncobs, and bare hands have all been documented in our struggles to keep up appearances. Sometimes the choices our ancestors made are wince-inducing; shards of pottery were used in Roman times. A gentler if less sanitary relief could be found in the form of the tersorium, a communal stick with a vinegar-soaked sponge on its end. (The one literary reference to the tersorium stems from the writings of the Roman philosopher Seneca, who describes a gladiator killing himself by thrusting the tersorium down his throat, blocking his windpipe and choking himself to death).

An array of pre-toilet paper implements from Japan, c. 710-784. (Photo: Chris 73/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

An array of pre-toilet paper implements from Japan, c. 710-784. (Photo: Chris 73/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

Yet the sheer multiplicity of implements co-opted for the grim task speaks clearly to their unsatisfactory nature.

Unsurprisingly it was the country that first invented paper that first invented toilet paper. In 589 AD, the Chinese scholar and government official Yan Zhitui agonized over the correctness of using paper that had Confucian quotations written on it to wipe his bottom with. Indeed as Richard Smyth reveals in his breathtaking tome on the subject, by the 14th Century the province of Zhejiang dominated the toilet paper market, providing the Imperial court in Nanjing with special toilet sheets that were three foot long by two feet wide.

The first mention of toilet paper in Western literature is not favorable. It comes in Francois Rabelais’ supremely scatological Gargantua(1534) in which the titular giant discusses how through “long and curious experience” he has “found out a means to wipe my bum.” Having tried sheets, curtains, table-cloths, hay, straw, wool and cats to do the deed, Gargantua announces that by far his worst choice was paper:

“Who his foul tail with paper wipes

Shall at his ballocks leave some chips.”

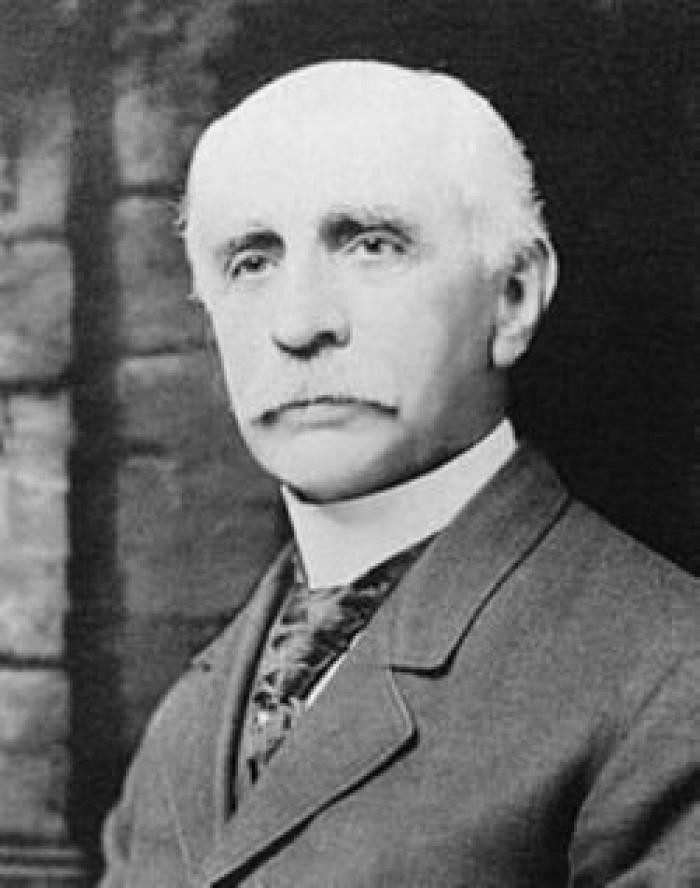

Joseph C Gayetty, the inventor of toilet paper. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

As it was, the sheer cost of paper made it impractical as a wipe until the 19th century when the arrival of thick and cheap publications such as the Sears Catalog and the Farmer’s Almanac saw them put to double use. The Almanac was even published with a hole in it so it could be hung off a nail in an outhouse. However it was in 1857 that an American inventor named Joseph Gayetty announced the arrival of the first purpose-made toilet paper—“Gayetty’s Medicated Paper For the Water-Closet.”

Gayetty was a shrewd businessman. He took aim at his greatest competitors—the newspapers, magazines and catalogs people were already using in their toilets— and in the truest American tradition, used fear to sell his wares.

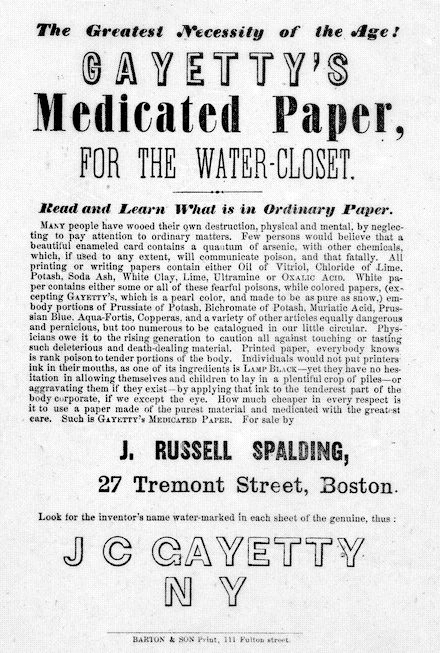

“The Greatest Necessity of the Age!” An 1859 avertisement for Gayetty’s medicated paper. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

“Many people have wooed their own destruction, physical and mental, by neglecting to pay attention to ordinary matters,” read his broadside advertisements. He warned that printed paper contained “Oil of Vitriol” and” Chloride of Lime” and other “fearful poisons” and declared that improvised toilet papers introduced “rank poison to tender portions of the body.”

Gayetty’s medicated paper was, by contrast, made to be “pure as snow.” He thus declared his product “the greatest necessity of the age!” which, despite his abject scaremongering, did not seem entirely hyperbolic.

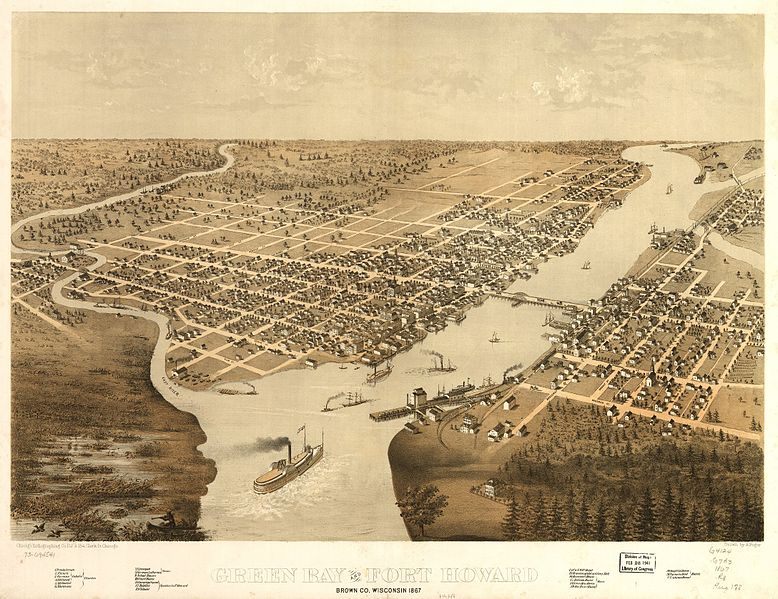

A bird’s eye illustration of Green Bay, Wisconsin, c. 1867. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Yet toilet paper was still a niche product, reserved for the rich or hemorrhoidal. It was not until the popularity of indoor plumbing took off—and the pages of the previously used catalogues proved unflushable—that the paper mills of Green Bay turned their covetous eyes on the nation’s backsides. Perhaps it was not surprising that Green Bay should have achieved such coprophilic success. After all, the area had originally been named La Baie des Puants, “The Bay of Stinkards,” by early French explorers because of the odiferous green algae in the water.

Whatever the case, in 1901, Northern Paper Mills of Green Bay issued the first “sanitary tissue” called Northern Tissue. Each pack had 1,000 sheets of 4x10 inch paper that were pierced with a wire loop to hang from a nail. The product was such a success that by 1920 Northern Paper Mills was the world’s largest producer of bath tissue. Competitors sprung up and production of toilet paper doubled between 1925 and 1935. Such was the success of the toilet paper industry that it helped Green Bay avoid the worst effects of the Great Depression.

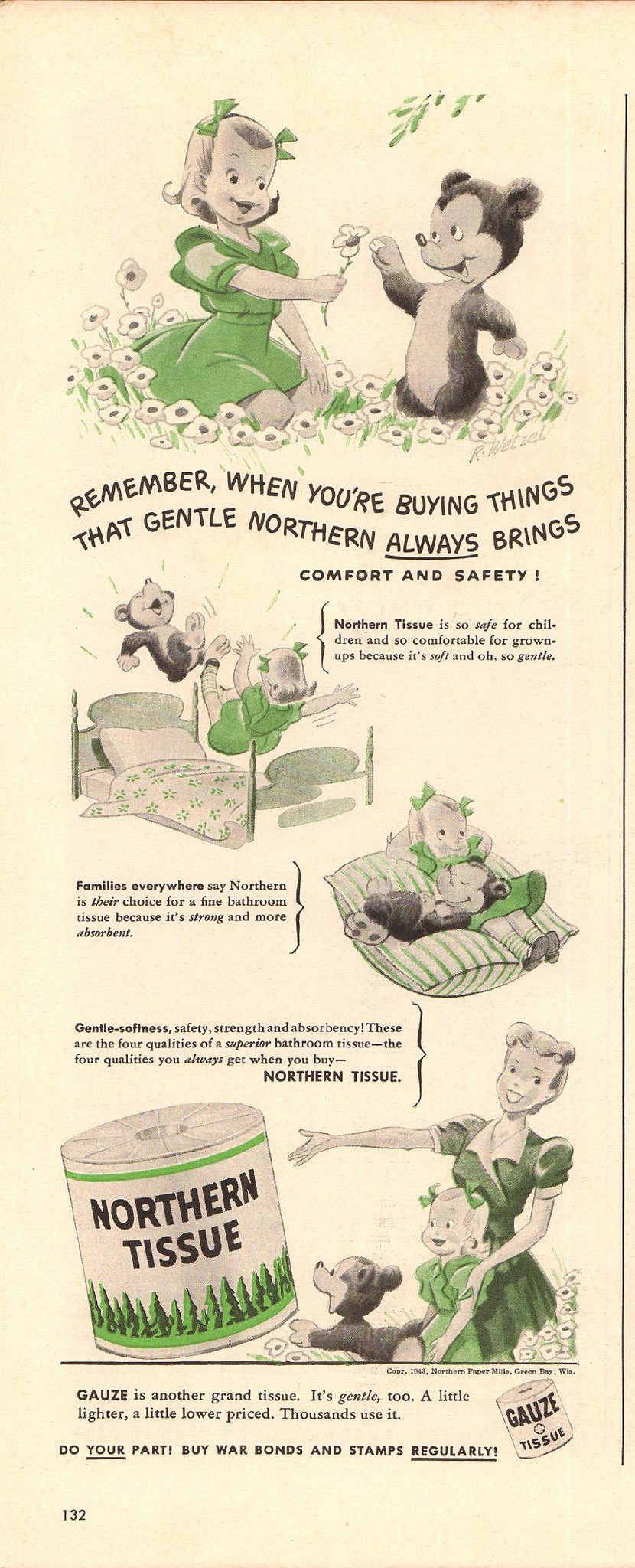

A 1943 advertisement for Northern Tissue. (Photo: SenseiAlan/flickr)

A serious problem did emerge. Toilet paper, like most paper of the time, was made from wood chips. These were pulped, treated, cooked and washed. However the process was not perfect. Small pieces of wood would often be embedded in the paper, making for an occasionally shocking surprise. Nearly 400 years on Gargantua’s foul pronouncement on paper wipes— “shall at his ballocks leave some chips”—was ringing true.

Fortunately the engineers at Northern Paper worked ceaselessly to develop the method of “linenizing” paper which made toilet paper both softer and, vitally, “splinter-free”. Indeed so important was this discovery that “Splinter-Free“ soon became Northern Tissue’s slogan and led it and Green Bay’s toilet paper manufacturers onto national and global success.

Chamin packaging from the 1930s through to the 1970s. (Photo: Courtesy Charmin)

Chamin packaging from the 1930s through to the 1970s. (Photo: Courtesy Charmin)

After millennia of scraping around in the dark, mankind had finally found a bottom-wiping tool that was neither too dangerous nor too disgusting. So the next time you bend over and swab the decks, think of Green Bay. It’s thinking of you.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook