How Our Make-Believe Relationships With Celebrities Shape Our Social Lives

It’s in our nature to want to form relationships with others—even if they don’t know who we are.

Jaye Derrick has a special relationship with the television sitcom Friends. Years ago, she began to notice a recurring pattern: whenever she had a fight with her boyfriend she would turn on her television and watch reruns of the popular sitcom. From her sofa in Buffalo, New York, Derrick noticed that Ross, Rachel, Joey, Chandler, Monica and Phoebe were beginning to feel like an extended group of friends.

Following the group’s zany dramas and misunderstandings with one another—and seeing how they propped each other up—provided Derrick with a sense of support when her own personal life was on the rocks. The show’s theme song “I’ll be there for you” rung true for her. She soon purchased a DVD box set of the show.

“Watching these episodes seemed to be taking away some of the feelings of rejection or distracting me long enough that the argument wasn’t a problem anymore,” says Derrick, a social psychology professor at the University of Houston in Texas, who was inspired by her relationship with Friends to study the phenomenon known as parasocial relationships.

These are one-sided, non-reciprocal relationships, often with a celebrity or other media persona. Parasocial relationships are strong emotional bonds with people you’ve never met and who do not relate back to you—or can’t, if they are fictional characters. These relationships grow as you seek out more information about the person, reading magazine articles, watching interviews on YouTube, and discovering their intimate likes and dislikes on Instagram or Twitter.

Joey, Monica, Rachel, and Ross really can be your friend, parasocially. (Photo: Giphy)

People have formed parasocial relationships with an array of popular and surprising subjects, from television characters to real-life actors, singers, and public figures. If you have imagined that Jennifer Lawrence is your best friend, have a secret romantic relationship with Kit Harrington, or created a universe where you could hang out with Harry Potter every day (I know I did)—then you’ve been in a parasocial relationship.

“In the work that [our lab has] done, we’ve seen that almost everyone has done this,” Derrick says of parasocial relationships. “As soon as you explain it, they say ‘oh my god. I do that.’”

Similar to real-world friendships, where the parties are continuously caring and nurturing for the relationship between meetings, often through social media, those in parasocial relationships are keeping up with the latest developments of their chosen star’s life, while waiting for the next TV show, album, or film to arrive. These days, Kim Kardashian’s feelings on various topics are less of a mystery than the feelings of many of those around us.

This common psychological scenario stems from our tendency to latch onto and identify with the people around us. In one-sided relationships, a screen is not a barrier. Even if that person will never know us or meet us, keeping up with their lives brings us joy. However, once fans know so much about the inner worlds of their favorite celebrities, it can be hard to feel at a remove from them.

“We as a species are dependent on social interaction to survive, and there is a part of our brain that can’t differentiate the face in front of me in real life with the face on TV,” says Gayle Stever, who has been studying fandoms and adult parasocial relationships for past 28 years at SUNY Empire State College in Saratoga Springs, New York. “It’s normal to be attracted to people in media, just as it’s normal to be attracted to people in real life.”

Do we know too much about the Kardashians? (Photo: Eva Rinaldi/CC BY-SA 2.0)

There are striking resemblances between parasocial relationships and the real life relationships we have with our siblings, best friends, coworkers, and romantic partners. Even though a celebrity or television character may not reciprocate your feelings, you experience the same emotional and psychological ups and downs in a parasocial relationship as you do in real life social relationships, says Derrick.

“Obviously with a parasocial relationship, they can’t provide physical support. So if you’re sick they can’t give you soup, but there are still parts of these parasocial relationships that seem to give us a sense of social support in the emotional sense,” says Derrick. “You feel like your TV characters are there, providing emotional support. They care about you.”

Parasocial relationships are found across ages, gender, social groups, and cultures. Studies by researchers at the University of Michigan and the University of Calgary surveying young adults revealed that 90 percent felt a strong attraction to a celebrity, 65 percent felt strong attachments to multiple celebrities, and 30 percent even wished to be the celebrity they admired, reports Pacific Standard.

In our media-saturated world, where many people see actors through screens more frequently than they see their close friends, parasocial relationships have become some of our most important relationships. And while you may you may not be willing to tell others of your secret relationship with Beyoncé, you should know that millions of others probably share a close imaginary relationship with her, too.

Even in adulthood, we still have imaginary relationships. (Photo: CandyBox Images/shutterstock.com)

While the phenomenon is generally associated with the rise of mass media in the 1950s, some psychologists believe that it stretches back much farther. “It’s definitely something that people have been doing ever since there have been stories and narratives around,” says Riva Tukachinsky, a communications professor at Chapman University in Orange, California.

The term, however, only dates to 1956, when Donald Horton and R. Richard Wohl introduced the idea of parasocial interactions, hypothesizing that people form “an apparently intimate face-to-face association with a performer.” As radio was ubiquitous and television was becoming commonplace, the first relationships studied were with news anchors and radio hosts. Horton and Wohl initially reasoned that these interactions were a result of isolation and lack of time spent with other people—a stereotype that wouldn’t be debunked until the late 1980s.

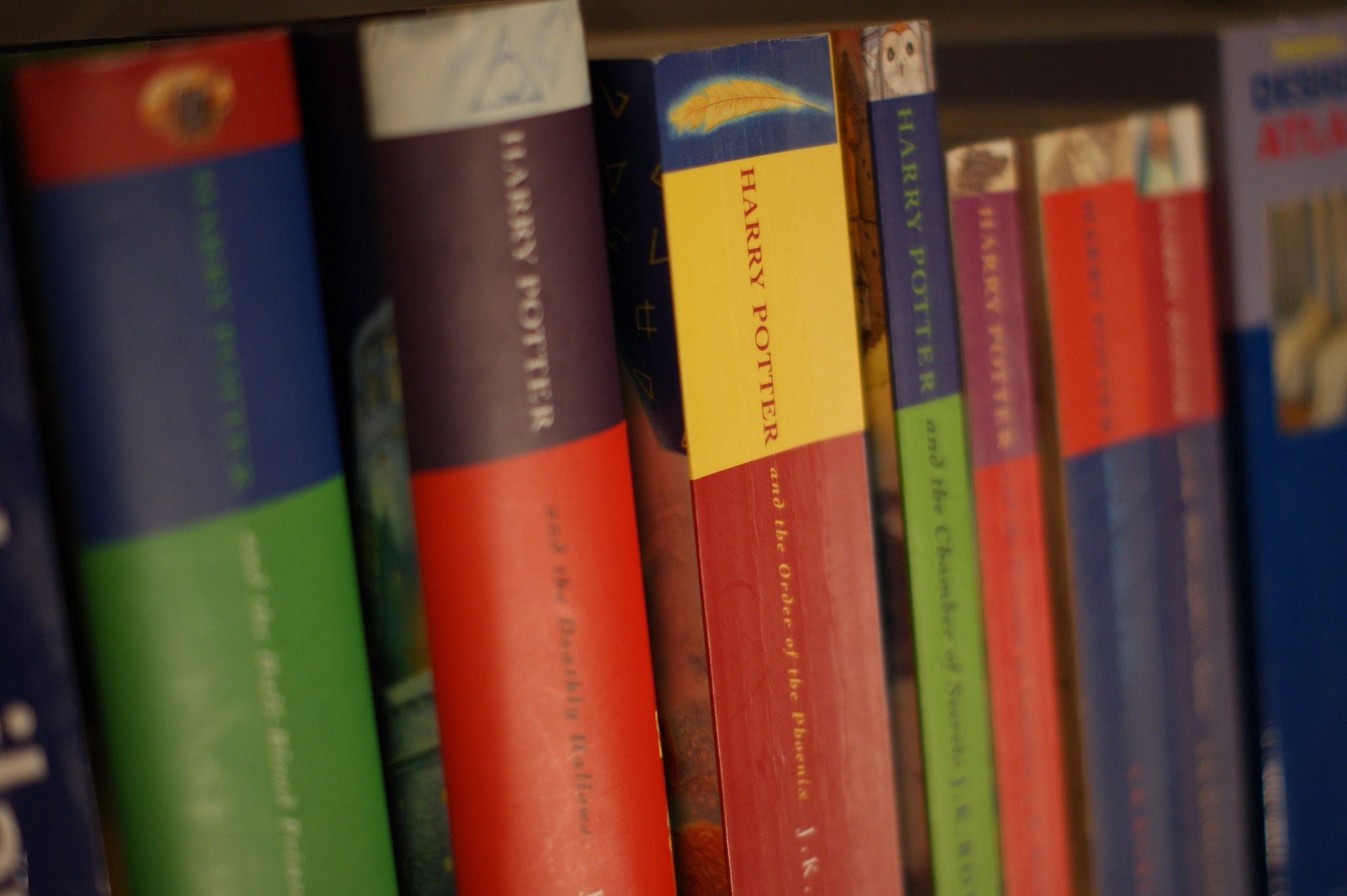

Parasocial relationships are not strictly limited to celebrities or television characters. Both Derrick and Tukachinsky have heard of research subjects having parasocial relationships with book characters, video game characters, and even cartoons.

Paraocial connections can be made with heroes and heroines in novels. (Photo: Sonia Belviso/CC BY 2.0)

We form parasocial relationships for different reasons. They can be used as an escape, as a cognitive development benefit, or simply as a source of enjoyment, explains Tukachinsky. How we think, feel, and fantasize about our favorite media personas is based on a brain that has developed to treat parasocial contact like direct contact.

Like our social relationships in real life, parasocial relationships vary in type and depth. Relationships can be profound and develop over decades, while others are more like casual acquaintances. A person can have multiple parasocial relationships—some are romantic, some are friendships, and some are mentorships. Lady Gaga fans, which she calls “Little Monsters,” for example, often refer to her as “Mother Monster.”

Most parasocial relationships are completely harmless—the equivalent of caring just a bit too much about Brangelina’s impending divorce. But the ones that get the most attention are the few cases where extreme parasocial relationships cross the line into stalking or other threatening behavior, generally in a person with underlying mental illness.

In 1981, John Hinckley Jr. believed he was in relationship with Jodie Foster, and thought by shooting Ronald Reagan he could get her attention. He was later not found guilty by reason of insanity. Margaret Mary Ray, who suffered from schizophrenia and believed she was married to David Letterman, was arrested eight times for trespassing on the television host’s property, and stealing his Porsche. Ray was convicted of stalking, and spent much of her sentence in a psychiatric hospital.

Lady Gaga - or ”Mother Monster” to her “Little Monster” fans. (Photo: proacguy1/CC BY-SA 2.0)

Various kinds of parasocial relationships can serve different functions throughout life. Stever categorizes parasocial contact into three tiers of varying intensity: parasocial interactions, parasocial relationships, and parasocial attachments.

Parasocial “interactions” occur while you are physically consuming the media, and begin to feel emotionally invested in it. Whenever you scream at a character to not go into the dark creepy cellar alone, or to break up with a vindictive boyfriend, you are interacting with the character. Shouting at a football player when he fumbles is a one-way parasocial interaction, an expression of frustration that he will never hear.

Meanwhile, parasocial “relationships” form when you continue to think about the celebrity in question when everything is turned off. During the height of the Twilight series, teens and college students expressed their parasocial relationships with both actor Taylor Lautner and his character Jacob Black, even sometimes referring to the two interchangeably, says Tukachinsky. Some parasocial relationships are powerful enough to influence big life changes. Mae Jemison, the first female black astronaut in space, spoke about how she was inspired by Star Trek actress Nichelle Nichols who played the original Lieutenant Uhura—the lone black woman on the bridge of starship Enterprise.

“When I relate to someone and I’m thinking about them when I’m not watching the show, that’s a parasocial relationship,” explains Stever, who studies the Star Trek fandom extensively.

People can become deeply and emotionally invested in their parasocial relationships, which can be reflected in things like trending Twitter hashtags that show support, pressure a media outlet or program to make changes, or simply express heartbreak when a character dies.

Mae Jemison (left) was inspired to become an astronaut by Nichelle Nichols (right) and her portrayal of Lieutenant Uhura. (Photo: NASA/Public Domain/Public Domain)

Parasocial “attachment” runs a little deeper. An attachment develops when a person has a desire to be close to someone in order to feel more secure. Stever interviewed a woman with stage four cancer who could only get through her chemotherapy sessions by listening to songs by Josh Groban—the presence of his voice comforted her.

Aspects of the attachment phenomenon can be age-specific. Children often form relationships with cartoon characters, which can play a role in socialization and facilitate learning. Teenagers have been found to have romantic parasocial relationships with celebrities; it’s now seen as a normal part of adolescence. Several researchers noted that parasocial relationships can help the elderly overcome the loss of a loved one.

In some cases, parasocial relationships can serve as a kind of therapy. For one of her studies, Stever interviewed a recent divorcee, who would watch reruns of The Andy Griffith Show online because seeing the community of characters reminded him of his childhood growing up in a small town similar to that on the show.

Josh Groban in concert. (Photo: lev radin/shutterstock.com)

Stever has also encountered widows who noted that their parasocial relationships have led them to consider dating again. She met a widow in her mid-fifties standing outside of a Josh Groban concert. Her husband had died of cancer a few years before, and when the widow realized that she was attracted to this singer, she was stunned she could still have those feelings. “She said, ‘I’m thinking about maybe dating again,’” recounts Stever. “I hear that a lot.”

People in parasocial relationships can also experience messy breakups. Tukachinsky recalls a student who came to her office in tears, and between sobs explains that one of her favorite shows, All in the Family, was going off the air. She had formed a tight friendship with each one of the show’s main characters, and felt like “all of them were abandoning her all of a sudden,” Tukachinsky says.

The same feelings you experience during a real life breakup percolate when a show ends, members of a musical group go their separate ways, or when you simply lose interest and move on to your next parasocial relationship. People are also known to show a great deal of grief when celebrities die.

David Bowie fans gather around a memorial wall painting in Brixton in January 2016. (Photo: Mr Seb/CC BY-ND 2.0)

Such visceral displays demonstrate how influential parasocial contact has become, an aspect that has been enhanced by greater celebrity interaction through social media.

Platforms like Twitter have transformed the nature of parasocial relationships, both intensifying them and making them harder to define, as more celebrities actively interact with fans and share personal information. Through Twitter, fans now have the opportunity to hear back from a celebrity, eliminating the one-sided nature of parasocial relationships and transforming them into something closer to acquaintanceships.

@NiallOfficial Have a great day niall,stay happy and smile lots.I love you so much :)

— mishal (@fadedbIond) September 22, 2016

“While parasocial interaction is largely imaginary and takes place primarily in the fan’s mind, Twitter conversations between fans and famous people are public and visible, and involve direct engagement between the famous person and their follower,” Alice Marwick and Danah Boyd wrote in the International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies. “These interactions take the celebrities out of the realm of fantasy and reposition them as ‘real people.’”

In Marwick and Boyd’s study, they reviewed tweets of fans of multiple celebrities, including Mariah Carey. One fan explained why she followed her with a tweet: “I follow @MariahCarey becoz she has been with me through her music everyday of my life 4 the last 15 years! She inspires me!” Since there is now a possibility that Mariah Carey could respond, the parasocial dynamic shifts.

@ladygaga now that I found myself I have to admit that you inspired me to be myself. #Mothermonster #monster4life

— Anita ManDaHump (@AnitaManDaHump) September 21, 2016

Twitter creates a new expectation of intimacy that didn’t exist before, Marwick and Boyd conclude. Some celebrities, like Josh Groban, even recognize fans, or Grobanites, by their faces or Twitter handles, says Stever. While Groban doesn’t know each individual fan as they know him, he is aware of them as a group and follows their posts, Tweets and movements enough “to have a sense of who they are, how they think, and what they want from him,” she writes in one of her papers.

Mariah Carey. Social media creates a new kind of intimacy between celebrities and their fans. (Photo: Everett Collection/shutterstock.com)

Stever also notes that this direct form of contact has also caused frustrations, as people are still restricted from the celebrity and lack control over the relationship. One of the subjects she interviewed said “sometimes I feel frustrated by Twitter because he has all the power” and “sometimes I feel a bit teased by the situation-but it’s not like it’s fault.”

“If you’re tweeting at a favorite celebrity and they tweet back, I can imagine that some people may have more trouble dissociating reality from fantasy,” says Derrick.

Despite some parasocial relationships’ increase in intensity, the vast majority of people understand that it’s not a ‘real’ relationship—even if psychologically it feels like one. “People know that Justin Bieber isn’t really on the other end of the telephone,” she says.

Kate McKinnon as Justin Bieber. Most people understand they are not in a relationship with either of them. (Photo: Giphy)

For decades, many people endorsed Horton and Wohl’s 1956 conclusions about the phenomenon, that those who formed parasocial relationships were lonelier and had low self-esteem. Several studies in the 1980s attempted to link loneliness to parasocial relationships, but the connection couldn’t be made. Conversely, researchers from the University of Delaware discovered those people who seek more relationships in real life are more likely to form more parasocial relationships.

In a 2008 study, Derrick found that people with low self-esteem can benefit from parasocial relationships. “Thinking about a favorite celebrity allows low self-esteem people to become more like who they would ideally like to be,” she says. They also provide those people with safe and reliable relationships (unless, of course, the television show ends, or your favorite character dies.)

Social relationships lie on a spectrum, says Tukachinsky. Some relationships are more imaginary than others. Even parts of our real life relationships are imaginary to an extent. When we talk about what our good friends are doing, based on their Facebook posts or Instagram feeds, we don’t actually have much more insight than when we discuss the movements of Taylor Swift.

Yet parasocial relationships are real relationships. The person on the other end of the relationship may never know you, but those feelings you form when you read a blog about them or watch them on screen are real. Expanded media offerings have expanded our network of human connections, too.

“A lot of people talk about this online trend as being isolating—now you don’t have real friendships,” says Derrick. “That doesn’t look like that’s the case. Parasocial relationships are really normative. If you’re good at making friendships in the real world you’re also good at experiencing parasocial relationships.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook