How Photographers Captured the Incarceration of Japanese Americans During WWII

A new exhibition examines a dark history.

Photographer Toyo Miyatake was 14 when he arrived in America in 1909, and 46 when he was forcibly moved from his home in Los Angeles to the Manzanar incarceration camp. By then, he was a father of four and owner of a photo studio. As he and his family gathered their belongings—whatever they could carry—he grabbed a few items that were considered contraband: a lens, a shutter, and film holders.

The events that led to the Miyatake’s imprisonment had been rapid, but they were the result of well-established prejudice. In February 1942, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. Less than three months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the order established a “Pacific military zone” in California, Washington, and Oregon, from which “any and all persons” could be excluded. The language was deliberately nonspecific, but it authorized the incarceration of 120,000 citizens or legal residents of Japanese descent.

But, as the new exhibition at New York’s International Center of Photography (ICP) points out, anti-Japanese sentiment had a long history on the West Coast. “It [the exhibition] begins with migration of Japanese Americans to the United States in the late 19th century, and details some of the racism they experienced built on preexisting anti-Chinese sentiment,” says Susan Carlson, an assistant curator at the ICP. For example, Issei—first-generation immigrants—were not allowed to become naturalized citizens. In 1920, noncitizens were prohibited from buying land. Laws of this type, says Carlson, set “the stage for the general sentiment before the bombing of Pearl Harbor that allowed things to escalate.”

“Relocation notices,” as they were called, appeared shortly afterward. Japanese Americans had less than a week to register and pack up their lives before they were moved to “assembly centers”—another euphemism. At these temporary detention centers—at fairgrounds or in stables—each family was given a number. Then they were moved to one of 10 camps across the country.

Carlson notes that this use of innocuous-seeming language was a way to mask intent. “The euphemistic language that they were adopting—the language of ‘evacuation’—was as though they were protecting Japanese Americans, but of course it’s the opposite,” says Carlson.

The exhibition originated at the Alphawood Gallery in Chicago in 2017, partly, adds Carlson, “because it was the 75th anniversary of the signing of the Executive Order, but partially because it seemed to have resonance with contemporary discussions regarding the travel ban or other political events.”

To tell some of the stories of incarceration, the exhibition includes the work of Miyatake, as well as that of Dorothea Lange and Clem Albers, who were employed by the War Relocation Authority (WRA); Hikaru Carl Iwasaki, the WRA’s only Japanese-American photographer; and Ansel Adams, who was invited to Manzanar by the camp’s director.

The exhibition includes many personal stories alongside the images. One of Lange’s photographs shows a store with the banner “I Am an American” draped across it. A note states that the storeowner, Tatsuro Masuda, commissioned the sign the day after Pearl Harbor. He and his wife never returned after their incarceration.

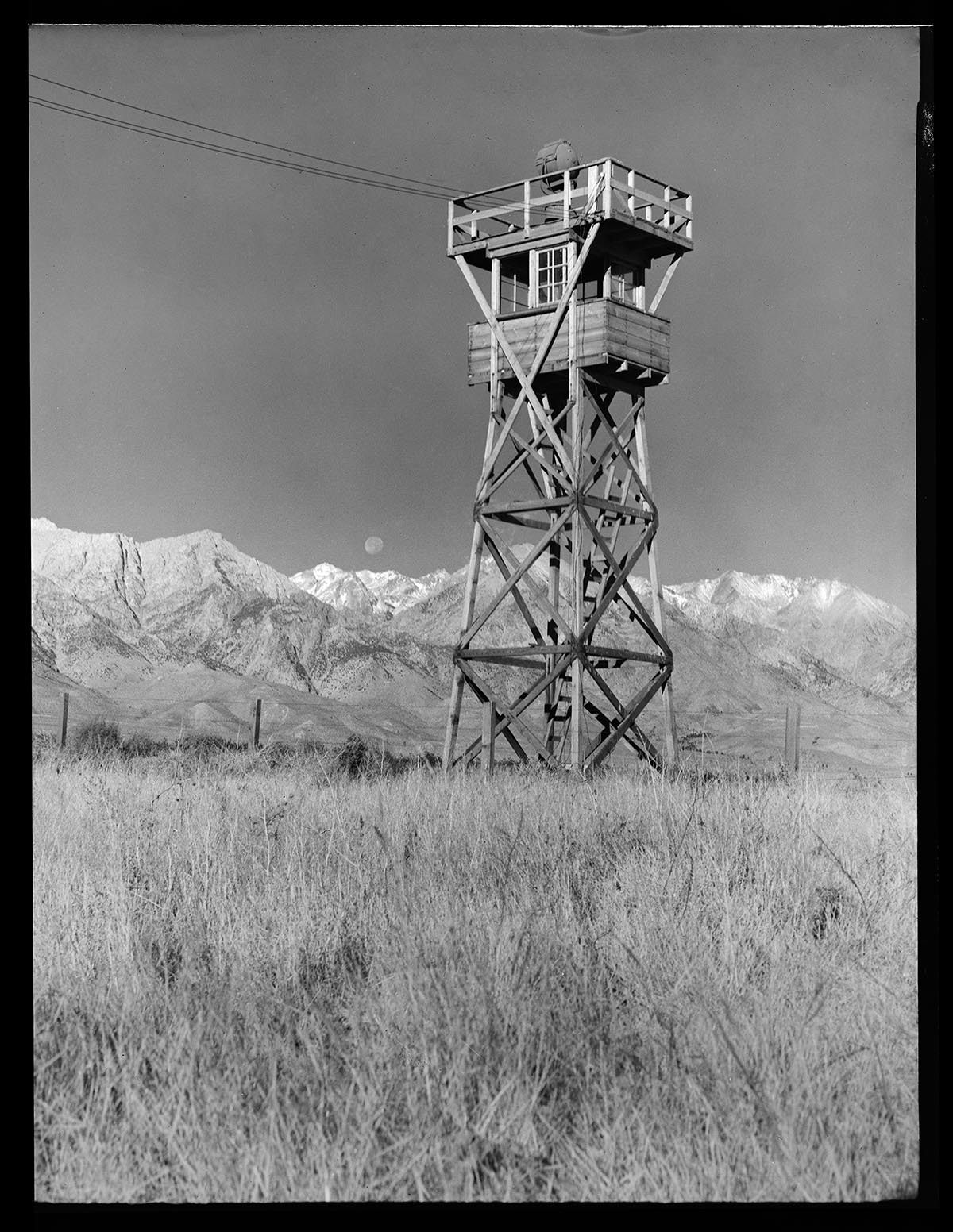

Lange’s remit was to record the experience of Japanese Americans, but for the WRA it was a propaganda exercise. Lange, and others employed by the WRA, were not permitted to photograph barbed wire or guard towers. (An image by Clem Albers featured in the exhibition shows three guards with guns on a tower. It was censored by the WRA, and a version still exists in the National Archives with the word “impounded” scrawled along it.)

Lange struggled with the assignment and, at one stage, reportedly had a nervous breakdown. “I was employed a year and a half to do that, and it was very, very difficult. I had a lot of trouble, too, with the army. I had a man following me all the time,” she later recalled. The WRA took possession of Lange’s work once her assignment was completed. Aside from a small number of photographs published in the anti-incarceration booklet Outcast and in an article by Lange’s husband, Paul Schuster Taylor, her work was impounded for the remainder of the war.

Unlike Lange, Adams did not work for the WRA. His photographs, which he published in a 1944 book called Born Free and Equal: The Story of Loyal Japanese Americans, have come under criticism for being a more sanitized portrayal of Manzanar. (The WRA must have found the images sufficiently palatable as, according to Lange, they “okayed” the book.) “It’s interesting because Ansel Adams was so well intentioned,” says Carlson. “But to me the problem is that—the subtitle of his project Born Free and Equal uses the phrase ‘Loyal Japanese Americans’ and it’s buying into the premise that there are disloyal Japanese Americans, when in fact there is no evidence that any Japanese Americans were engaging in any sabotage in any way. So I think that’s problematic—sorting out the loyal from the disloyal, rather than attacking the entire premise of the incarceration that was based on nothing.”

According to Carlson, Adams’s book was also criticized at the time for taking too sympathetic a view of incarcerated Japanese Americans. Lange herself was underwhelmed: “ … it was the only thing of its kind that he’s ever tried to do, and he’s pretty proud of himself on that one. He doesn’t know how far short it is, not yet,” she said in 1960. Carlson sees Lange’s work as more emotional and impactful. “There’s a lot of pathos” in her images, Carlson says, whereas Adams portrays the detainees “as dignified and strong and resilient, and you can see that in the portraits—they’re cropped very close, shot from a low angle.”

Miyatake had another perspective entirely, as a professional photographer and a detainee. He concealed his makeshift camera—with the lens attached to a drainpipe, in a wooden box—and began to shoot the camp secretly. According to his son Archie, Miyatake felt compelled to document the experience. “As a photographer, I have a responsibility to record the camp life so this kind of thing will never happen again,” he said. Miyatake was found out several times but, eventually, the director at Manzanar permitted him to shoot as the official camp photographer. Initially, only a non-detainee—a white person—could actually push the shutter, but eventually this restriction was relaxed.

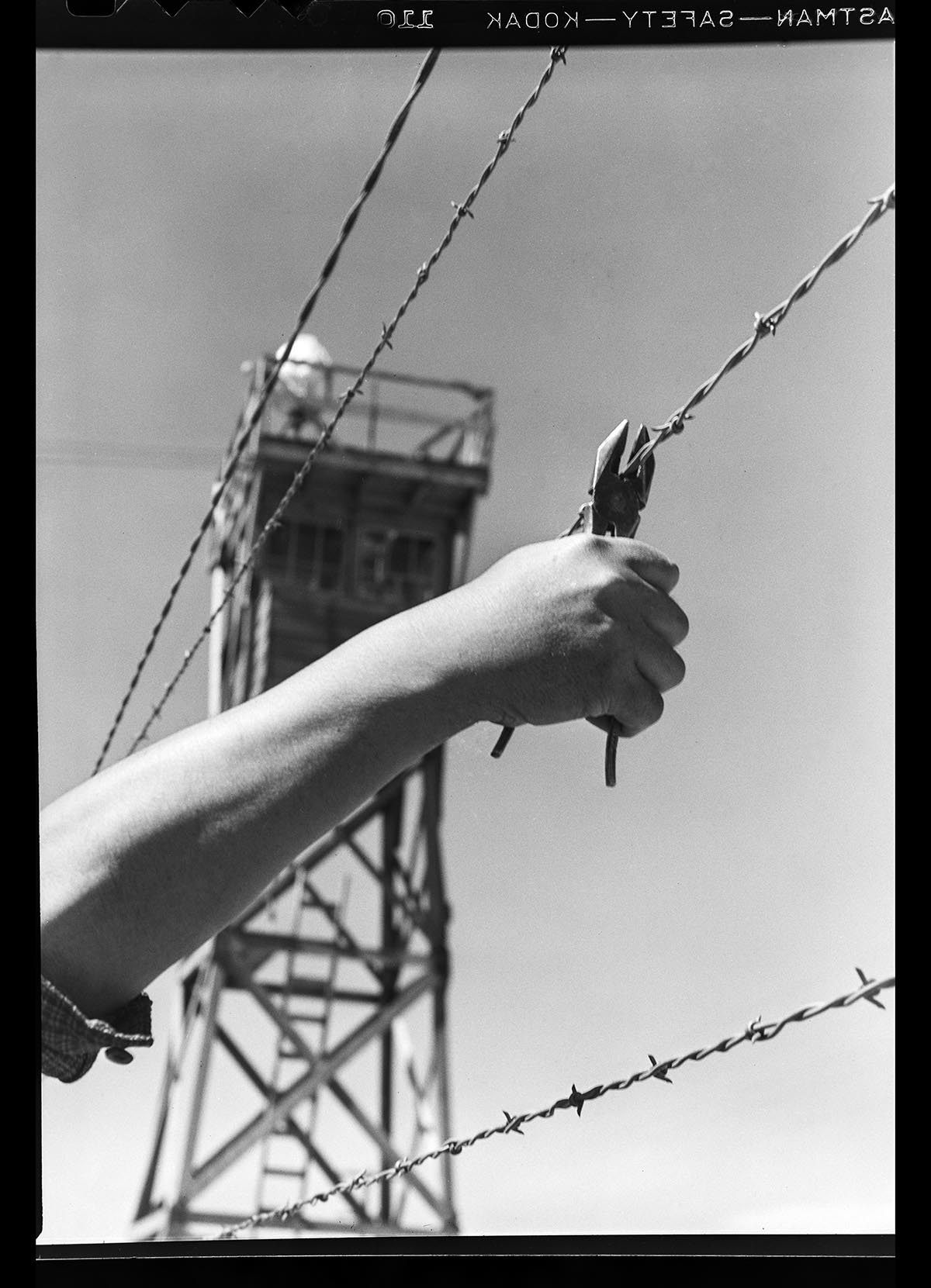

“Miyatake’s work is incredible for a number of reasons, having been a professional photographer in Los Angeles prior to the war,” says Carlson. “To me, I see him as working in a symbolic, artistic vein. You can read his images on a symbolic level very easily.” Miyatake’s work moves beyond the documentary. “It’s more getting to the heart of what is was to be incarcerated. And while the WRA photographers and Ansel Adams had been told not to photograph things like barbed wire and guard towers, those feature prominently in several of his images. He also was able to capture more intimate moments, like meeting a newborn baby, without being an obstructive presence. I think there’s a lot to be said of how much of his work would have been impossible under the WRA. It’s very much an intimate, personal perspective.”

Detainees who were deemed “loyal” began to be released in 1944; the last camp closed in 1946. Of the 120,000 detainees, two-thirds had been natural born citizens, and none had received any due process before incarceration. In 1988, Congress recognized that these events were “motivated largely by racial prejudice, wartime hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.” Any living survivors were entitled to $20,000 in compensation. A letter of apology from President George Bush followed in 1991.

Miyatake and his family were held until 1945. Before they left Manzanar, his son Archie posed for a photo: a hand holding clippers poised to snip barbed wire. Archie’s own son Alan is also a photographer. In an interview last year, on the occasion of the 75th anniversary of Executive Order 9066, he said that even if he retired, he would still curate his grandfather’s work: “The photos help us remember what happened. I would still want to make sure everyone who wants to see them gets to see them.”

Then They Came for Me: Incarceration of Japanese Americans During World War II is open from January 26, 2018, to May 6, 2018, at the ICP Museum in New York.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook