How the Jeans Capital of the World Moved from Texas to China

A still from China Blue, a documentary about jeans production in China. (Photo: Chun Ya Chai/ Courtesy Teddy Bear Films)

A still from China Blue, a documentary about jeans production in China. (Photo: Chun Ya Chai/ Courtesy Teddy Bear Films)

Blue jeans are up there with with Donald Trump and the right to bear arms as uniquely American creations. But each time you pull on a pair of blue jeans there is a good chance your bottom is being cradled by a product made in Xintang, China, the jeans capital of the world.

A small city in the heavily industrialized Pearl River Delta area of Guandong province, Xintang is completely devoted to the item of clothing Yves Saint Laurent called “the most spectacular, the most practical, the most relaxed and nonchalant.”

Three hundred million pairs of jeans are made in Xintang a year—that’s some 800,000 pairs a day—in both state-of-the-art factories and back alley workshops. Cotton, mostly imported from the United States, is cut and sewn, dyed and washed, distressed and sandblasted here. Three thousand businesses are linked to the trade, employing nearly 200,000 workers. Even schoolchildren are put to work in the industry, snipping loose threads off jeans for fractions of a Yuan.

The question, though, remains: How did a Chinese city end up making a quintessentially American product?

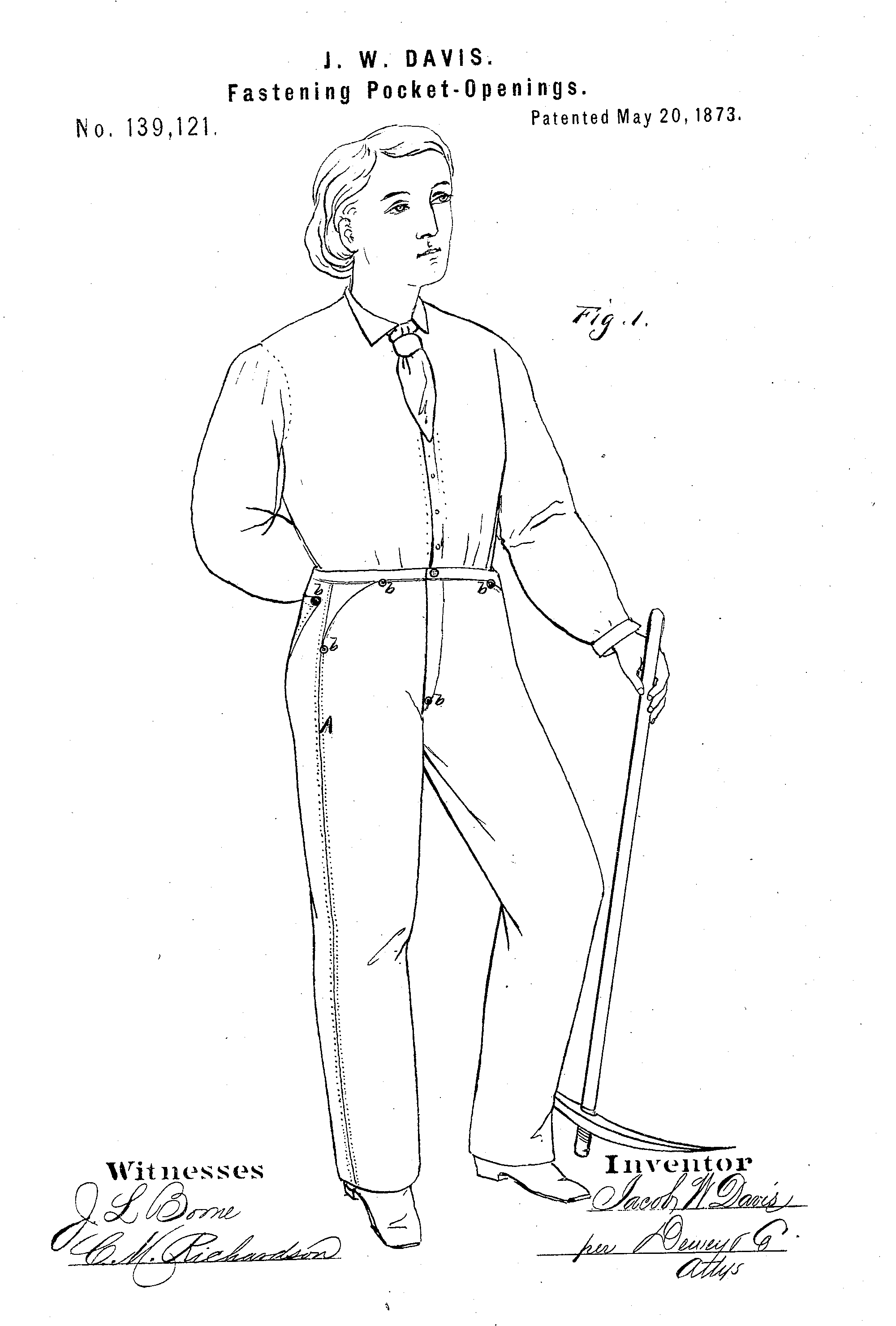

Levi Strauss and Jacob Davis’ 1873 patent for riveted pants. (Photo: Google Patents)

Levi Strauss and Jacob Davis’ 1873 patent for riveted pants. (Photo: Google Patents)

Every capital is built on the ruins of its rivals. In the 1970s and 1980s the jeans capital of the world was located in El Paso, Texas. Thousands worked here creating jeans for Levi’s and Lee, Guess and Gap, Joujou and Jordache. Ancillary businesses huddled around El Paso—zipper and rivet concerns, printing and marketing enterprises— indeed, the city was home to so many industrial laundries used to wash the jeans that it also managed to bag the title “laundry capital of the world.”

But the blue jean business was changing. It was going global. In the 1980s jeans were no longer just a fashion statement but, to many inhabitants of the Soviet Bloc, they were a symbol of Western freedoms (they still are). The French philosopher Régis Debray declared that there was “more power in blue jeans and rock and roll than the entire Red Army.” Blue jeans held within them a rare combination of revolution and comfort. The whole world wanted a pair and would knock down walls to get them.

Denim on the Berlin Wall, 1989. (Photo: Lear 21/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

Denim on the Berlin Wall, 1989. (Photo: Lear 21/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

In China, itself gradually opening up to the outside world, jeans seemed less revolutionary than exotic. Denim was just one aspect of American culture that was catching the Chinese eye (Westerns were another). So, rather than demonize them as the Soviets had done, China appropriated them. Xintang was, at the time just a small agricultural town known mainly for producing bananas, but as jeans manufacturers in Hong Kong sought cheaper labor they began to relocate there. With rock-bottom wages and government assistance, the industry boomed.

Jeans on sale in Shanghai. (Photo: Cory Doctorow/flickr)

Jeans on sale in Shanghai. (Photo: Cory Doctorow/flickr)

By the mid-1990s El Paso’s jeans industry was in steep decline—a pair of jeans could be made in Xintang for a quarter of the price. Some production went across the border to Mexico, but China was able to ramp up production on an unprecedented scale, aided by its own vast domestic demand (people in China own, on average, 4.2 pairs of jeans). In 2008 the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences bestowed upon Xintang the snappy title of “Best Denim Clothing Industrial Zone among China’s 100 Best Industrial Zones” and with that a strange reversal had taken place. Twenty years before, blue jeans had played a significant role in the destruction of one communist regime; now they were being created in outsize numbers by another.

What’s more, these blue jeans were now being shipped back to be sold in the United States. Free trade had helped neuter the most potent of capitalist symbols.

From the documentary China Blue. (Photo: Chun Ya Chai/ Courtesy Teddy Bear Films)

From the documentary China Blue. (Photo: Chun Ya Chai/ Courtesy Teddy Bear Films)

Or had it simply helped transform it into a different kind of symbol? Despite Xintang’s unequivocal position as jeans capital of the world, it is famed not so much for its astounding production of pants as for the ecological devastation it has wrought. A 2010 Greenpeace report revealed that the dust in Xintang’s streets is blue, the water in its rivers indigo, and the lungs of its workers embedded with fine silica. It has been calculated that one pair of Xintang jeans requires 3625 liters of water and 3 kg of chemicals to make. (If you’re looking for information about how the workers themselves live, a 2005 documentary called China Blue has some depressing footage.) The American blue jean that once bespoke relaxation and non-conformity has, in its new Asian home, become the harbinger of an ecological nightmare.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook