Found: A Mummification Recipe From Prehistoric Egypt

New research shows ancient embalmers were using resins and gums far earlier than we thought.

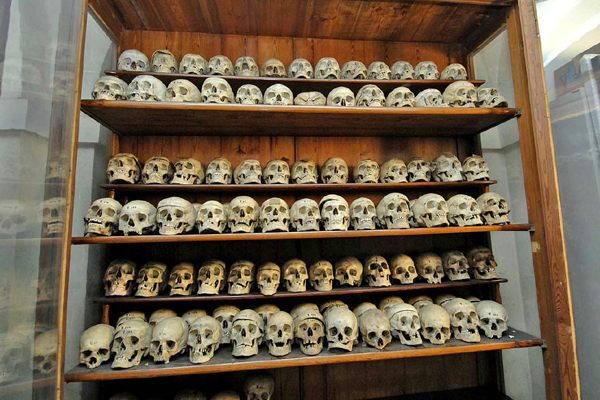

Thousands of years ago—long before he arrived at the Egyptian Museum in Turin and became known as S. 293, the oldest preserved body in the collection—a man died in the desert. Estimates place his death somewhere in the vicinity of 3600 B.C., but it’s hard to say exactly when he perished or where his remains were found. There are no provenance records for the remains before 1901, when an Italian Egyptologist purchased the mummified body from a dealer and delivered it to the museum. S. 293 has spent millennia curled on his left side, knees tucked up toward his elbows. Judging by wear on the man’s teeth, he was probably in his 20s or 30s when he died.

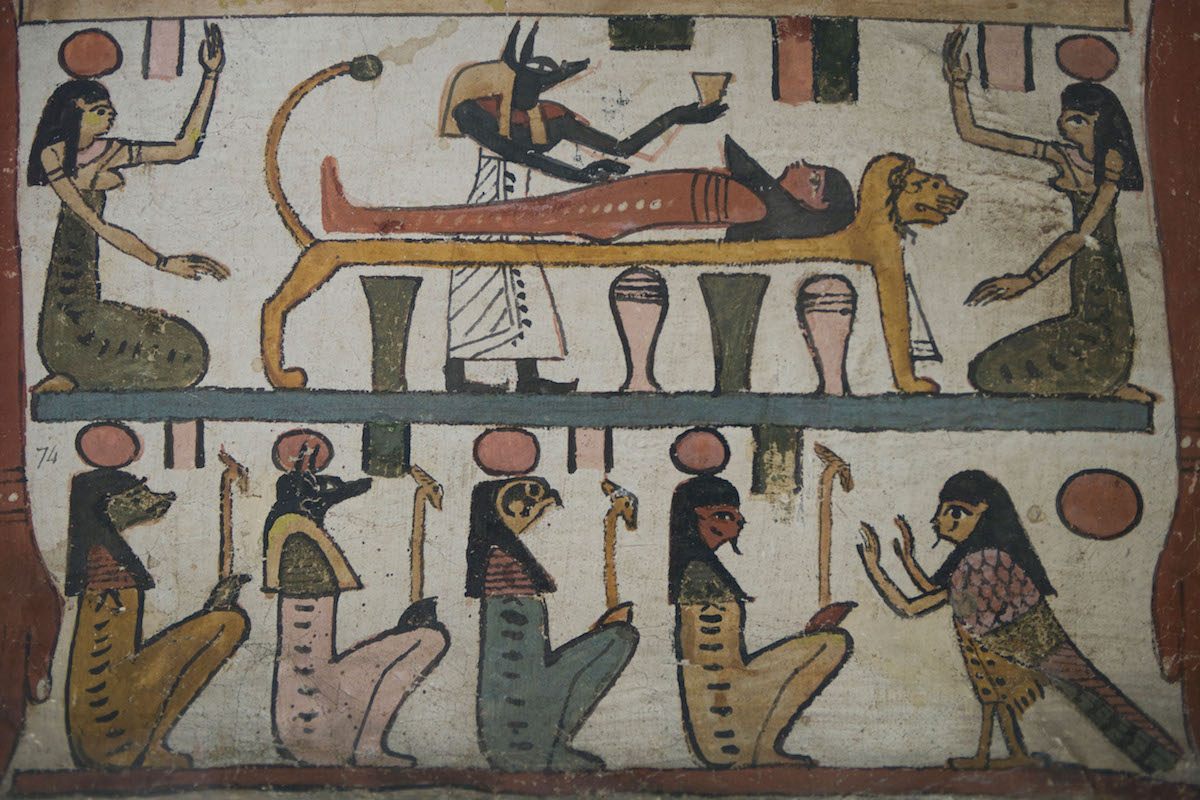

Researchers had long assumed that this mummy, like many others that predate Dynastic Egypt (which begins around 3100 B.C.), was preserved somewhat spontaneously—desiccated by the natural scorching and parched sand of a shallow desert grave. Scientists have often considered this hands-off approach to be a major precursor to the painstaking process of deliberate mummification that was refined over the next 2,000 years and reached its apex during the New Kingdom era (c. 1550–1070 B.C.), when embalmers excised organs and drained fluids before swaddling a corpse in strips of linen.

But in a new paper in the Journal of Archaeological Science, a team of researchers led by Jana Jones, an Egyptologist and honorary research fellow in ancient history at Macquarie University in Sydney, makes the case that this was no accidental mummy. Instead, they suggest it was the result of a carefully concocted recipe.

Back in 2014, Jones detected traces of fats, oils, and resins on funerary textiles from graves in Upper Egypt, dating to between 4500 and 3350 B.C. To Jones and her collaborators from Oxford and the University of York, these findings suggest that bodies were preserved using specific ingredients long before experts had thought. At the time, the researchers only had the textile scraps, and the bodies themselves weren’t available for study. “Museums are very jealous of their collections,” Jones says. “Egyptology is a very conservative science.” But the museum in Turin allowed the team to come in and work with S. 293. The mummy was particularly appealing because it hadn’t undergone any known conservation work that could adulterate its chemical signatures.

In textile fragments from strips encircling the body’s torso and wrists, the researchers found plant oil, conifer resin, and a plant-based sugar or gum. “These would have been lightly heated and mixed together,” Jones says. “The chemistry shows evidence of heating, which is why we can refer to them as ‘recipes.’” The researchers believe that the resin and aromatic plant extracts functioned as antibacterial agents—and they would go on to become the main preservatives in later mummification, too, Jones says.

“It’s fair to say that the natural environment and being buried in the hot dry sand certainly played a part in the preservation of these prehistoric mummies, but what’s important here is that there was also an artificial—anthropogenic—treatment of these bodies with ‘balms,’” says paper coauthor Stephen Buckley, an archaeologist at the University of York. Jones thinks the textile wrappings may have been dipped into the mixture, then wrapped around the body; Buckley suspects that the concoction was slathered on with some sort of stick, though he hasn’t found one yet.

It’s easy to think we know mummies—they can be such familiar figures in both museums and movies—but there is still a great deal to learn about their early years and how they came to be. Jones won’t be the one to do it, though: “I’m going to retire after this!”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook