How Archivists Deal With Redactions, Codes, and Scribbles

Sometimes, obscurity leads to surprising intimacies.

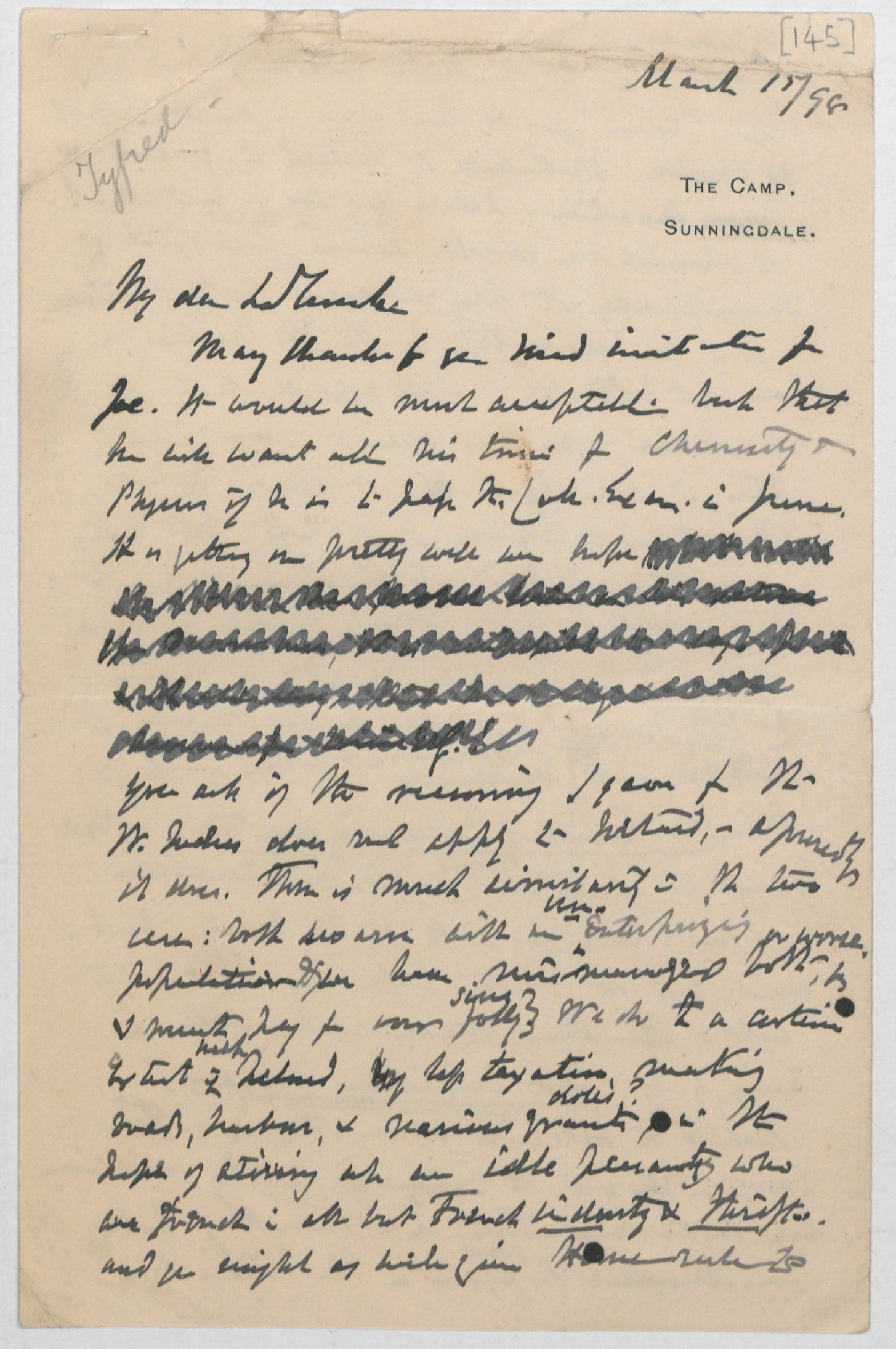

On March 15, 1898, the eminent botanist Joseph Dalton Hooker sat down at his desk, picked up a pen, and started writing a letter to his friend and confidant, the Reverend James Digues La Touche. “My dear La Touche,” he began, before continuing what had been many years of correspondence, updating his pen pal on his family life, his intellectual preoccupations, and his professional exploits.

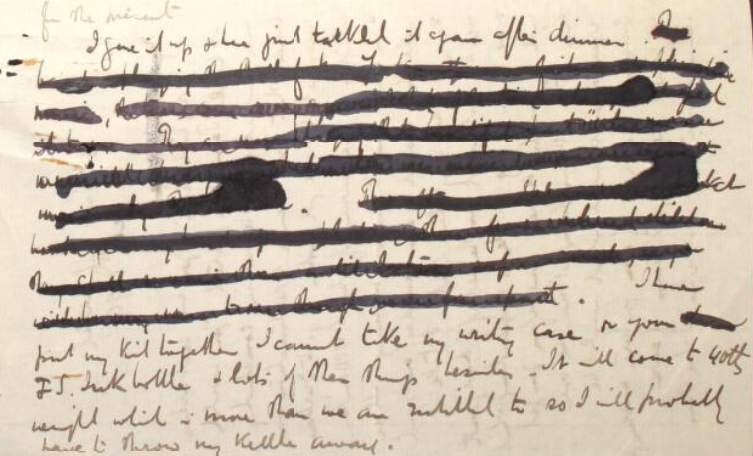

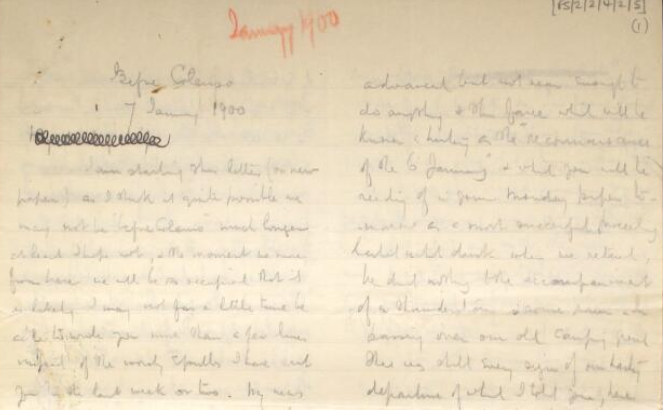

Over a century later, an archivist at Kew Gardens in London—the largest botanical garden in the world, where Dalton served a long stint as director—reached into a folder of the pair’s correspondence, drew out a page, and stopped cold.

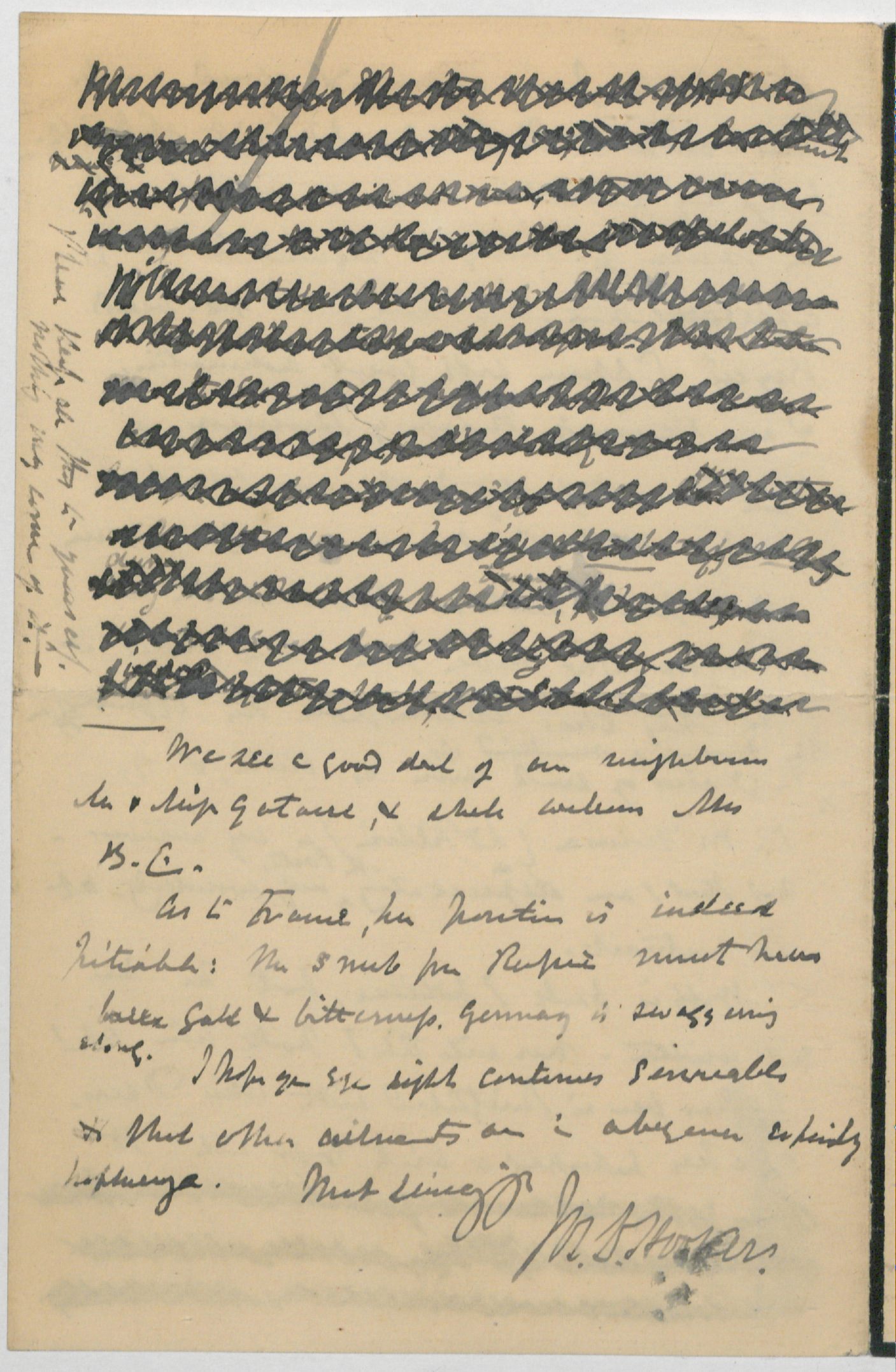

The archivists were already deep into the process of digitizing and transcribing Hooker’s letters for posterity. But a few lines into this particular letter, the words suddenly disappeared, censored by row after row of black squiggles. The same went for a number of Hooker’s missives to La Touche. “We were quite mystified by it,” says Virginia Mills, an archivist at Kew. “They stood out to us, because we hadn’t come across anything else like it in his papers. So we just started kind of speculating about what it might be.”

Kew Gardens has thousands of pages of correspondence from Hooker. Of these, only a small percentage of lines are blacked out. But these pages play an outsized role in the imaginative life of those who work with them. “The letters are full of unpublished material, private thoughts, scientific exchange and criticism, and intimate details shared with friends and family,” writes Mills in a blog post about the letters. “But perhaps most intriuging of all, to those of us who have got to know the collection, are the stories that remain obscured.”

We picture archives as airtight troves of information, where historical documents go to be explicated, contextualized, and preserved. But there are plenty of ways for mystery to wriggle in. “When I was asking my colleagues in other archives, almost all of them could think of an example” of something that simply could not be read, says Mills, each of which presents different problems and opportunities.

In some cases, obscurity is professionally (or personally) required. Codes, for example, seem to be favored by two very different types of people: businessmen seeking to protect their economic interests, and teenagers and young adults guarding their feelings.

Beatrix Potter, later famous for her children’s books, kept a diary written in a self-invented cipher that took a dedicated fan years to crack. Archivist Kathryn Boit, who once worked with the youthful diaries of physician William Clarence Lisle Richards, which she describes as “absolutely delightful, mostly recording his borderline obsessive crushes and hobbies.” “He used a code occasionally, which I never understood!” she writes.

The businessmen are equally cryptic. Now an archivist at SOAS university in London, Boit runs into a lot of code in papers from Butterfield & Swire. In 1920, the export business paid thousands of pounds to develop their own five-letter cipher, which, Boit writes, could get across everything from “lagbu” (“Act of God’) to “uzvap” (“Instruct the captain to drive his ship at full speed”). In this particular case, Boit says, decoding is easy, as “we also have the big volumes of the code in the Archive.”

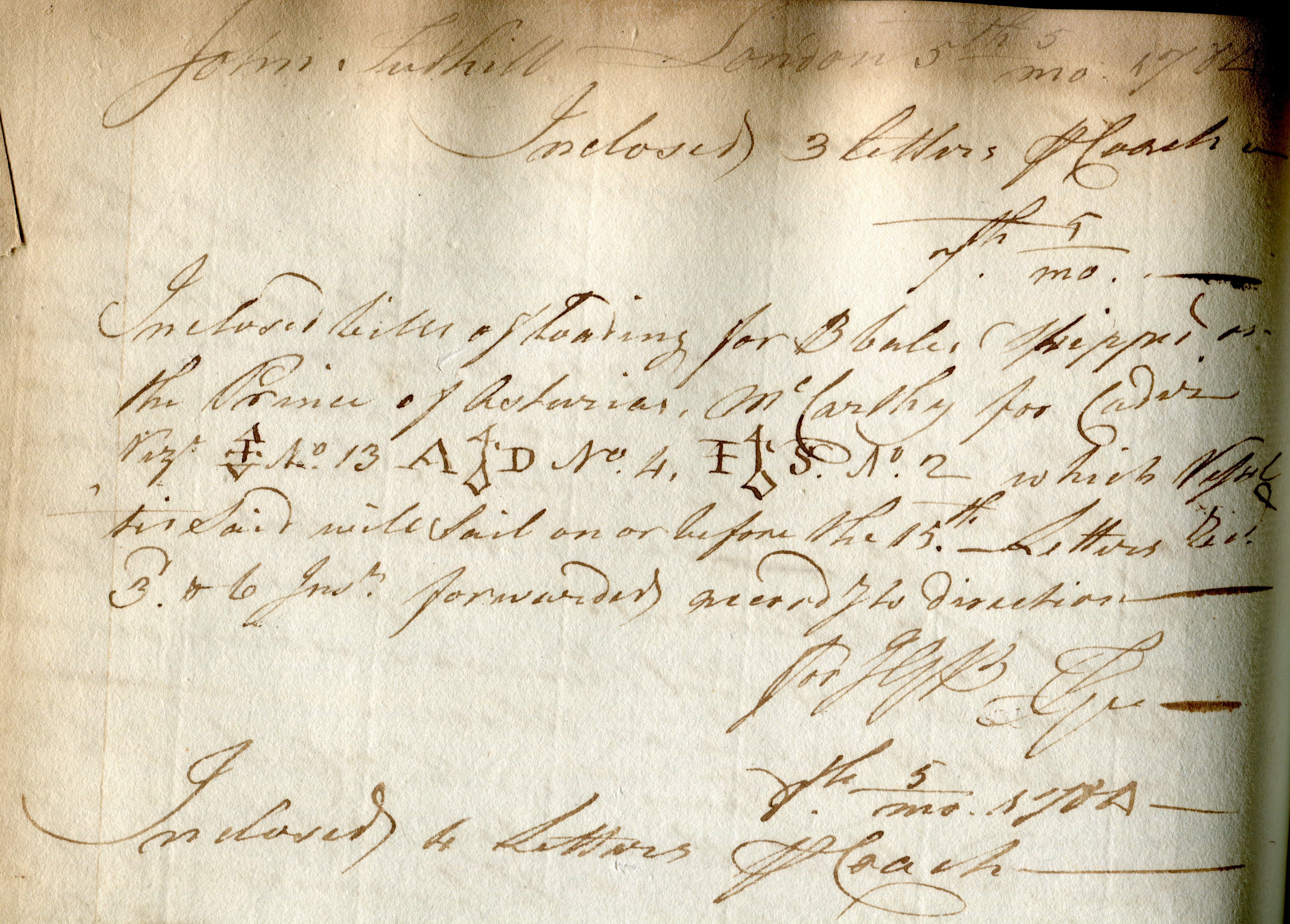

Jill Moretto, the heritage archivist for healthcare company GlaxoSmithKline, has a more mysterious code to grapple with. She oversees a series of letterbooks used by some of the company’s founders, which have strange, cross-shaped symbols sprinkled throughout.

Because the company shipped pharmaceuticals overseas, she says, she expects the symbols were sent to customers to help them pick up their goods: “to tell [them] which ship the goods were on, and dates of sailing perhaps, encoded so that if it was intercepted the secret was safe.” It’s also possible they matched symbols painted on the crates themselves. “I’ve yet to find a key to these,” she continues, “so parts of the letters are essentially hidden.”

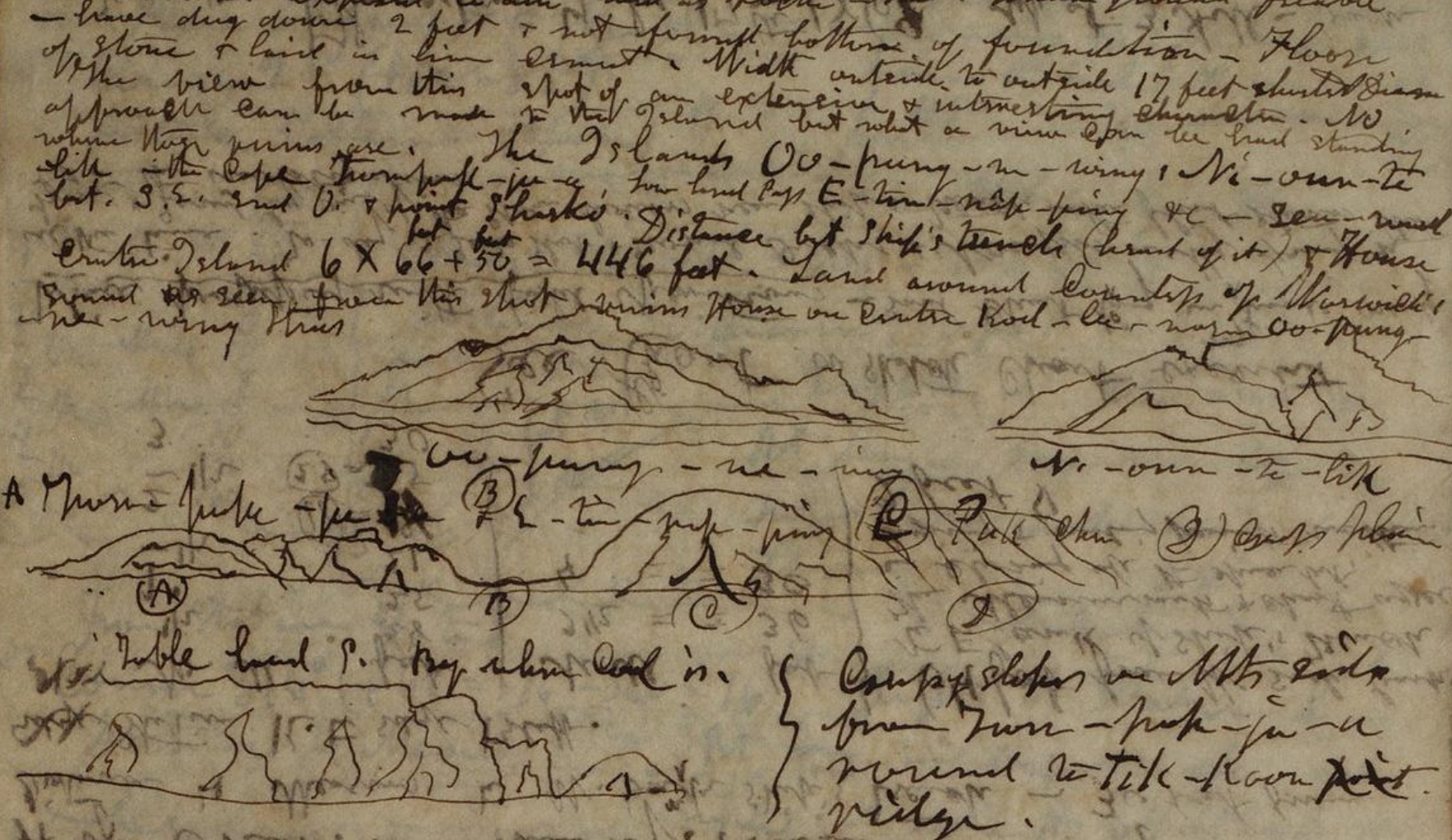

Other forms of illegibility are almost certainly unintentional. Take the Arctic notebooks of 19th-century explorer Charles Francis Hall, which were recently digitized by volunteers (known as “volunpeers”) at the Smithsonian Transcription Center, and a portion of which can be viewed below. The problem is quickly apparent. “When Hall is sitting down at his desk, his handwriting is flawless,” says Andres Almeida, the Center’s project coordinator. “But when he was out exploring, it’s something to make you go cross-eyed.”

When the eyes finally uncross, though, the rewards are great. Sometimes, a single volunpeer will decide to focus on a particular source, and end up developing a close and fruitful relationship with their subject. “You start hearing the voice of the person sometimes,” Almeida says. Such is the case with Hall’s journals. They have a dedicated transcriber, who, after spending so much time with the explorer, has developed an eye for his quirks, says Almeida.

Redaction and censorship—like that found in the Hooker/La Touche correspondence—is also not uncommon. As Mills explains, searching for the motivations that inspired it can be another way of getting to know the text. Some of these motivations we would now call prudish: One of Mills’s colleagues at the Kew Archives pointed her to the diaries of explorer Richard Spruce, later published, and red-penned, by Alfred Russell Wallace.

“Wallace has crossed out certain passages about Amazonian women and menstruation—things he thought at the time weren’t suitable to be published,” says Mills. “It gives you an idea of what the sensibilities at the time were.”

But other times, the motivations are nearly as mysterious as the hidden words themselves. Lorna Cahill, an archivist at the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons in London, has a trove of letters the veterinarian from Frederick Smith in which almost all the personal details are blacked out—even the greetings. “It is not entirely clear why he has redacted the salutations,” she says. “It appears that he only wanted to keep what would be historically interesting, and decided terms of endearment with his wife wouldn’t be!”

Such is the case with Hooker’s blacked-out letters. After they found them, “we just kind of started speculating,” says Mills, using what they knew of Hooker’s life and legacy to undertake a sort of historical detective work. A biographer who had transcribed the letters in 1913 had also omitted the occluded passages, suggesting that the censorship happened before that date.

They also knew that after Hooker’s death in 1911, the letters probably passed from La Touche’s household back to his own. This gives clues about who did it: “It could have been that they were redacted before, by a member of La Touche’s family,” says Mills. “Or it could have been that [Hooker’s wife] redacted them before she gave them to the researchers who were writing the biography of her husband. We think those are probably the two most likely culprits.”

The “how” is obvious—a thick black marker—and so that leaves the “why.” This has proven to be the trickiest and most rewarding part of their detective work. As Hooker and La Touche spoke frankly about then-controversial topics like the age of the Earth, and no one blocked that out, political censorship is an unlikely motivator. “We thought that maybe it’s not scientific content they’re worried about removing—it’s more likely to be personal information.”

Specifically, they think it might be comments about two of Hooker’s children, Reginald and Joseph, who were tutored by La Touche. “Maybe they’re very personal comments about the childrens’ performance, their education, their intelligence, that kind of thing,” says Mills. “It forces us to kind of think about the family dynamic, and to consider what their personal concerns might have been.”

This is another type of closeness, an opportunity to reexamine the life of someone you thought you knew inside and out. But because it just piques further curiosity, both for the archivists and the researchers that use their collections, it’s a bittersweet one as well. “The fact that they didn’t want it seen almost makes you more interested in what it might say than you would have been otherwise,” says Mills. And there it lies, right in front of your nose, but impossible to see.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook