In the Early 1900s, Robber Barons Bought Dozens of Centuries-Old European Buildings. Where is Medieval America Now?

Crates of monastery stones and statue of the King of Seville arrive in Miami. St. Bernard de Clairvaux was dismantled and shipped from Spain by William Randolph Hearst. (Photo: Bettmann/Corbis)

We had been driving through what felt like one continuous Miami strip mall for almost an hour. Our GPS promised that in a few short minutes we would reach the destination we had traveled some thousand miles to find: a Spanish monastery, from the 12th century, once inhabited by a bevy of monks, moved stone by stone across the ocean, now set in the middle of a swamp-jungle. As we passed each pawn shop, shuttered record store, and strip mall-based high school, it became increasingly plausible that perhaps the guidebooks, Wikipedia, and Catherine Zeta Jones’ jarringly kinky scene from Rock of Ages had somewhat oversold whatever we were about to experience.

When the GPS told us to turn left, our earlier suspicions were confirmed. The side streets did not really offer an escape from the strip mall, but merely extended it in all directions.

Then, suddenly, on the right, a break in the uniform storefronts. A little further on, a small sign announcing the Ancient Spanish Monastery.

At the back of the parking lot, a wrought iron gate blocked off a graceful 16th century gate just wide enough for a small truck. Mary and Bernard of Clairvaux looked down lovingly from delicate niches on either side of the gate, their gazes falling on a cluster of cats that had found shade next to the plastered support posts. It was the quintessential Southern Mediterranean/Under the Tuscan Sun vibe, except, in the background, giant tropical plants, complete with dangling vines. The trees loomed over a church, courtyard and dining hall built in the middle of nowhere in Spain almost nine centuries before. From the gate, we could see bright flowers splayed against the pitted stone, a little worse for the wear after 900 years of use, a trip across the Atlantic ocean, several fires, and a quarter-century sabbatical in the damp crates of a Bronx warehouse from the 1920s to the 1950s.

The exterior of St Bernard de Clairvaux, Miami. (Photo: Jorge Elías/flickr)

This was Medieval America—one of several dozen centuries-old buildings imported to the U.S. in the early 20th century. They lie scattered around the country, a hidden patchwork of mostly-illegal monasteries and mansions whose history has been largely forgotten. In reporting this story, Atlas Obscura dug into both scholarly and journalistic texts, and spent time on both coasts, to understand how and why a handful of the country’s most famous families spent small fortunes helping themselves to whole European buildings. The story that emerged is part caper, part mystery, and part tragedy: American robber barons snuck ancient stones out of the war-torn countryside in the dead of night, Europeans fretted over how their familiar landmarks were rapidly disappearing, and U.S. cities spent decades of the 20th century fighting over what to do with tens of thousands of displaced medieval remnants.

How to Steal a Monastery

There are two Americans to thank for the strange fact of a 12th century Spanish monastery’s existence only a few miles from Miami Beach: notorious plutocrat William Randolph Hearst, and his art dealer, Arthur Byne. Together, these two men thwarted Spanish authorities, angry townspeople, and all common sense to drag not one, but two monasteries to the shores of America.

In December 1926, the New York Times printed a brief article on Hearst’s importation of St. Bernard de Clairvaux, stone-by-stone, from Segovia, Spain. William Randolph Hearst was no stranger to the Times—a newspaper magnate, short-lived Congressman for New York, and perpetual tabloid fixture for his high profile romantic affairs and fights with fellow tycoons, Hearst had a proclivity for spending money in the most ostentatious, self-congratulatory ways. A regular Times reader of the era would not be surprised to hear that Hearst had imported an entire medieval building.

The Map of Medieval America: From Florida to California, the U.S. has a whole village worth of medieval buildings hiding in plain view. Here are 20 of them, in whole and in parts, mostly open to the public as museums (or parts of museums). But this map barely scrapes the surface of the stories behind these structures, which have endured arduous journeys to their current resting places.

The complexity of that achievement was given scant space. The journalist covering the purchase included only a brief note on the obstacles Hearst faced in dismantling and moving a monastery out of Spain: “Twice during the work of removing the cloister, the villagers, banding together, drove the workingmen away on the ground that foreigners were robbing the community of its greatest treasure.” The article went on to assure readers that “the cloister will be the only precious work of art allowed to leave Spain for a law passed two months ago prohibits further exportation of works of art and ruins.”

Yet just five years later, 11 ships filled with the pieces of a second Spanish monastery bought by Hearst docked in San Francisco Bay, in spite of the new laws. Who let this happen? And why were Americans buying, shipping and reconstructing medieval European buildings in the first place?

The answer to both of these questions was, at least in part, Arthur Byne. In 1930, Byne, a renowned American dealer of Spanish art, stumbled upon the monastery of Santa Maria de Óvila, nestled in a small valley created by a bend in the River Tagus in central Spain. Byne had developed something of a complicated reputation in the country since arriving there 20 years earlier. In 1910, Byne undertook his first trip through Spain to photograph and catalog the nation’s medieval monuments. He soon earned the trust of the Spanish government and its art community and became a leading expert on Spain’s cultural heritage, even receiving recognition from the king in 1927. But at the same time, Byne was leveraging these relationships to build a bustling business in the antiquities trade, exporting furniture, fireplaces, ceilings, statues, and other Spanish treasures to his American clients. “My only role in life is taking down old works of art, conserving them to the best of my ability and shipping them to America,” Byne reflected in a 1934 letter to Julia Morgan, an architect colleague back in California.

The monastery, a home to Cistercian monks beginning in 1180, had a typically medieval monastery plan, with a series of buildings constructed around a cloister with arcaded walkways. The church sat on the north side of the cloister, while the monks’ wing attached to the east side, which included the sacristy, the library, the chapter house and probably a common room for the monks. On the south wing opposite the church stood the refectory, kitchen, pantry, and a calefactorium (warming room). The bodega, a utilitarian building containing a long subterranean vault for wine storage, made up the monastery’s west side.

Upon encountering the site, Byne knew he had an ideal buyer in William Randolph Hearst. Hearst had a reputation as an unpredictable, but prolific, art collector; as one of his dealers assessed in a very backhanded compliment, “nobody I have known showed simultaneously such a voracious desire to acquire and so little discrimination in doing it.” Hearst also had a particular interest in Spain. He once wrote in a letter to his mother that Spain was “a tired, worn out monarchy” prime for exploitation by foreign elites. He declared, “[we] will burst through the Pyrenees into Spain, and ravage the country. How does that strike you?”

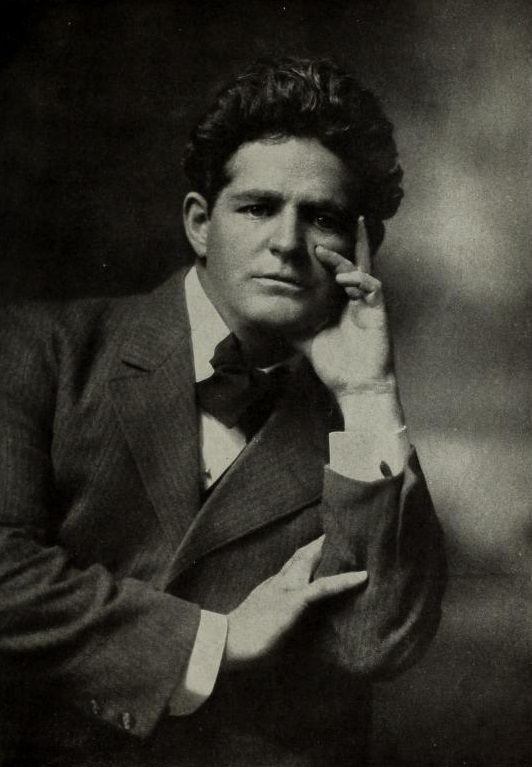

William Randolph Hearst, c. 1906. (Photo: Library of Congress)

William Randolph Hearst, c. 1906. (Photo: Library of Congress)

However, Hearst also had a specific goal in mind for Santa Maria de Óvila. It would be part of a 61-bedroom “medieval castle” in the California wilderness, called Wyntoon Castle. Hearst was less interested in historical preservation, and his design included a swimming pool constructed from Santa Maria de Óvila’s 150-foot-long chapel with a diving board installed on the site of the former altar. The choir at the north end of the church would serve as a women’s dressing room, and the chapel’s apse would be scattered with two or three feet of sand, creating a “beach” for sunbathing. After a series of exchanges with Byne, Hearst approved the purchase of the entire monastery.

From the moment Hearst agreed to shell out the cash—around $300,000 in total—Byne realized he was facing a number of challenges in moving a monastery, stone by stone, across the Atlantic Ocean to a California forest. Luckily, American money worked wonders on a weak Spanish government.

The first, and perhaps most pressing issue, was that taking a monastery out of Spain violated a host of Spanish cultural preservation laws, many of which the Spanish government had generated in the wake of Byne’s previous antiquities-purchasing binges. “It is forbidden to ship a single antique stone from Spain today—even the size of a baseball,” Byne himself admitted. Thus, Byne took extreme precautions in keeping his project quiet. Two of Hearst’s architectural consultants, Walter T. Steilberg and Julia Morgan corresponded about the “need for secrecy in this matter.” “I am not trusting, in this talkative country, to the discretion of any typist, and shall send all of my reports in pencil…” wrote Steilberg.

One of the ways Byne convinced the Spanish government to turn a blind eye to his pillaging was by convincing the Spanish Ministry of Labor that his project was a “partial solution to the serious problem of unemployment.” In the midst of a serious Spanish economic depression, Byne hired more than 100 local townspeople to dismantle the monastery. The disassembling process went quickly, thanks to the neat construction of the site—Byne described the monastery as “a joy to take down.”

The dismantled cloister of the Monastery of Ovila, 1930s, said by Byne to be a “joy to take down”. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

But moving the many heavy stones presented a more imposing challenge. Byne needed to transport the stones across the countryside to the port, about 100 miles away. However, there were no paved roads in this part of the country, nor did it have accessible railroad networks. Undeterred, Byne found the remains of a trench railway from Paris, a leftover relic of World War I, when Allied forces needed to deliver supplies to soldiers in the trenches. The railways were less expensive to build and could be easily moved and reconstructed, allowing Byne to quickly lay down tracks in Spain. The simple, makeshift rail lines previously used to deliver critical ammunition, food, and medicine to trench-bound Allied soldiers were now being used to move metal push carts filled with ancient stones through a Spanish valley.

But building a railway to transport one rich man’s illegal purchase was not enough. Byne’s workers also needed to get the stones across the River Tagus, which ran alongside the site. Hearst’s architects, in cooperation with the local workers, developed a pulley system that used the current of the riverto pull a raft filled with stones connected to a series of cables: It took the workers thousands of trips, over the course of six months, to get the stones across the 100-foot-wide river.

The instability of the Spanish government provided a final challenge for Byne and Hearst. When Byne began removing the monastery in early 1931, Spain had a largely ineffective monarchy and a sluggish economy. This helped Byne convince the government that monastery exportation was a boon to the Spanish economy—creating jobs and bringing in some much needed revenue. But it also meant that the government might collapse any day, and could be replaced with a new government less willing to ignore Byne and Hearst’s antics. In a March 1931 letter, Steilberg relayed:

Mr. Byne is very anxious to just remove from the site all the carved or moulded members, as he fears interference by the authorities at any time. We presented the entire matter to the national art commission and they were entirely agreeable to him taking this forgotten and shameful neglected and abused group of buildings; but it is quite possible that some of the politicians, in an effort to discredit those in power, may bring pressure to bear through the press that would halt the work at once.”

A month later, in April 1931, Byne’s fears were realized as the Spanish king fled the country, and an anti-monarchist regime came to power. But, luckily for the Americans, the Second Spanish Republic was about as effective as its predecessor when it came to protecting cultural heritage sites. Byne declared that the revolutionary Spanish government “(has) more important problems than to bother about than the demolition of an old ruin.” Time magazine later reported, “[Byne’s] workers nailed the red flag of revolution to the church they were illegally tearing down and went right on working.”

By the time the stone-laden ships arrived in the San Francisco harbor in 1931, Hearst and Byne faced a challenge even more imposing than angry townspeople and interloping Spanish bureaucrats: the Great Depression. As the stock market crashed, Hearst’s net worth plummeted and his desire for a personal medieval castle with a chapel swimming pool began to seem like a pipe dream. Estimates for the cost of completing the castle came in at around $50,000,000 and Hearst’s financial advisors finally convinced him that he could not afford to take on this expense. After all of Byne’s effort and ingenuity, Santa Maria de Óvila was retired to a warehouse, then dumped in a San Francisco park.

Why Buy A Monastery

The idea to buy a medieval building, dismantle it, ship it across an ocean, store it, and then rebuild it in a new location was not just a lavish fantasy formed in Hearst’s money-addled brain and turned into reality by an army of fearful yes-men. An English antiquarian noted somewhat darkly to the Manchester Guardian in 1926 that “there [seemed] to be a craze in the United States at the moment for this sort of thing.”

He was right. Significant portions of at least 20 medieval buildings made their way across the Atlantic, almost all between 1914 and 1934. As a result of this veritable industry, medieval structures now reside or resided in major cities across the country (New York, Philadelphia, Detroit, San Francisco, and Miami), as well as in regional centers (Richmond, VA; Toledo, OH; and Milwaukee; WI), and even in the middle of nowhere (Vina, CA).

American billionaires like Hearst and John D. Rockefeller, Jr. played a significant part in this trade, but they weren’t the only ones involved. Many wealthy folks seemed to consider the purchase of a medieval building a reasonable personal expense.

Segovia, Spain, where the St. Bernard de Clairvaux was originally located. The city walls date from the 8th century. (Photo: Carlos Delgado/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

The buildings were not that expensive, at least for an early 20th century American magnate. Even slightly less-rich people could afford them: An American diplomat and his heiress wife purchased a medieval English manor house and brought it to Virginia. The daughter of a railroad magnate had a Gothic chapel moved from France to her estate in Long Island, where she installed it next to a (now destroyed) Renaissance castle that she had acquired earlier. Most of the structures were little more than ruins after the Wars of Religion of the 16th century and the nationalization of religious institutions at the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th centuries. Governments in the 19th century had given the buildings to local, private owners for a song.

More difficult for the prospective medieval building owner was the politics. To facilitate the legally ambiguous trade, Hearst had Byne, John D. Rockefeller had George Grey Barnard, Virginia business people used Henry G. Moore. Stealing a monastery was all about networking.

But, speaking more broadly, the desire for such properties was probably rooted in the American interest in the European past. At the beginning of the 20th century, American elites began incorporating elements of medieval architecture into everything from universities to churches to department stores. By the time that Hearst, Rockefeller, and the others started importing medieval buildings, Americans had been collecting medieval art and sculpture in earnest for about 40 years. Americans wanted anything that could be labeled “medieval”: the sturdy, stark lines of the 11th century Romanesque or the effusive ornament of the early 16th century flamboyant Gothic, it didn’t matter.

Nowadays, the dominant cultural expression of the Middle Ages seems to be the sex and violence of Game of Thrones. But at the turn of the century, Americans thought of the era as a time of serenity; piety; and ideal, harmonious communities. Medieval Europe had not yet suffered the traumas of industry, and medieval objects became a way to demonstrate that the capitalism of the early 20th century had its genteel side. In the case of the 15th century Tudor manor house Agecroft Hall, the effect was supposed to be actually transformative. One pamphleteer writing about the arrival of the hall in Virginia claimed rapturously that “England [was] literally being brought to America.” She did not mean that America was claiming a part of England, she meant that part of the U.S. had been turned into a medieval English agricultural estate—an improvement.

Any coherence that the medieval buildings bought by Americans might have had in the 1920s and 1930s disappeared almost as soon as the buildings arrived in America. The Depression shifted financial priorities away from moving buildings across oceans and the fad for all things medieval had faded by World War II. The Medieval American buildings might have been acquired for similar reasons but soon after their arrival in the U.S., they began wildly disparate journeys.

What Happens When Your Building Arrives in America

A lot could go wrong even once a medieval building finally made it to America. Geopolitics, the global economy, and public health regulations all had unexpected consequences. And, of course, there never seemed to be enough money.

Even the buildings that would become The Cloisters, that venerable model of American medievalism, faced some challenges on this side of the pond. George Grey Barnard, an American sculptor and antiquities dealer who was deeply in debt and living in France, began in 1906 to acquire large portions of four monasteries: Sant-Miquel-de-Cuixà, Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert, Trie-en-Bigorre, and what he thought was Bonnefont-en-Comminges. He planned to sell the buildings to wealthy individuals and institutions from New York to L.A., but plan after plan fell through. By 1913, he had few prospects and was quickly running out of time, as laws forbidding the export of French monuments would come into effect on January 1, 1914. He threw the cloisters on boats as swiftly as he could—the authorities, who knew what he was doing, tried to stop him—and got the stones out in the nick of time.

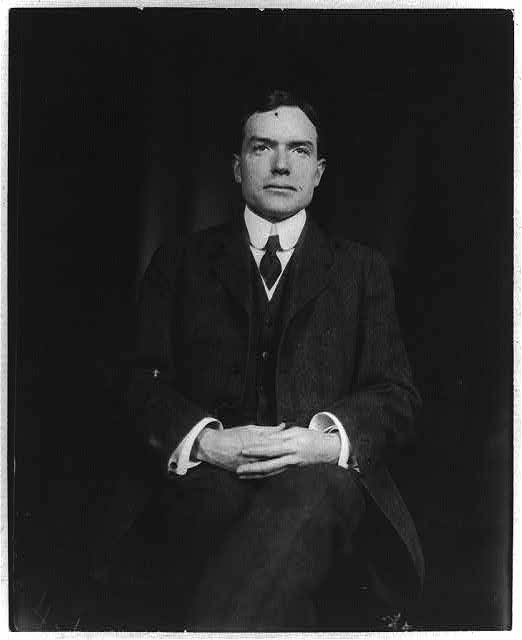

George Grey Barnard, sculptor and medieval art dealer, in 1908. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

In early 1914, these cloisters arrived in New York, and Barnard decided that he would keep them for the immediate future, creating an installation on some undeveloped land in Upper Manhattan. This predecessor to today’s Cloisters proved immensely popular, with papers heralding it as the Gothic jewel of New York’s cultural institutions.

By the mid-1920s, however, Barnard needed money, badly. He quietly let it be known that his cloisters, and the land they were on, were collectively for sale. Barnard’s agent approached John D. Rockefeller, Jr., on March 25, 1925, and offered everything for $1 million. Barnard had bought art for Rockefeller in the past, and the two had previously discussed the creation of a great museum of medieval objects. Now, with the fate of New York’s premier medieval exhibit uncertain, Barnard stressed to Rockefeller the importance of keeping his cloisters in the city if at all possible. With stronger antiquities laws in place, it could prove tricky for Rockefeller to simply go buy a new set of medieval buildings in France.

Rockefeller, a brutal negotiator, indicated his interest to Barnard’s dealer and then ceased contact with them for several weeks. Rockefeller then wrote to The Metropolitan Museum of Art with an offer to buy the cloisters for the museum, eventually settling on a donation of $500,000 to buy the buildings and an additional $300,000 to maintain them. A decade earlier, The Met had promised to buy Sant-Miquel-de-Cuixà from Barnard, but backed out. This time, the sale went through, and Barnard agreed to sell his cloisters to The Met for $650,000, a sum much lower than the million-dollar offers he had entertained in 1915 and 1922. By 1933, the cloisters were moved to Fort Tryon Park and were newly combined and augmented into the complex that is The Cloisters today.

Saint-Michel-de-Cuixa, late 1800s, prior to parts of it being dismantled and shipped to New York, where is makes up part of The Cloisters. (Photo: Bibliothèque de Toulouse/flickr)

Another Spanish monastery acquired with Hearst money veered even further off course. Before Hearst bought Santa Maria de Óvila in 1930, he had purchased another Spanish monastery: Saint Bernard de Clairvaux from Segovia, Spain. St. Bernard de Clairvaux charted a curious course from Spain to Miami by way of New York.

Byne got St. Bernard de Clairvaux out the same way he moved Santa Maria de Óvila, but this trip proved much easier. He built 40 miles of road through the mountainous Spanish countryside, hired more than 100 men and ox-cart teams to stomp down his newly laid roads, and constructed a 20-mile narrow-gauge railroad. Spain’s cultural preservation laws hadn’t been enacted yet, so Byne didn’t have to worry about interference from the authorities; he just slipped cash into the waiting hands of the dockworkers. In about a year’s time the monastery had been blueprinted, dismantled, packed into 10,571 crates and shipped to a Bronx warehouse, where it arrived in 1926.

Then the monastery landed in the crossfire of an international public health scare. Byne’s workers packaged the pieces of monastery stone with hay to cushion the blocks during the long journey across the Atlantic—standard practice, particularly when trafficking fragile goods out of a rural region. But in 1924, the United States experienced its seventh outbreak of the unfortunately named and highly contagious “hoof and mouth disease.” Past outbreaks of the virus had devastated American agriculture, as swine, sheep, and cattle broke out in the gruesome mouth and hoof blisters characteristic of the ailment. A 1914 epidemic of hoof and mouth disease spread across the eastern and midwestern United States, forcing farmers to slaughter 200,000 diseased animals at an appraised value of almost $6 million. The USDA believed that the disease had come from overseas, as both Europe and Latin America had experienced epidemics.

When Spain experienced another eruption in 1925, the USDA was not taking any chances. American authorities figured the odds were good that the hay used to pack Hearst’s crates had been exposed to animals in Europe and demanded the quarantine of all 10,571 crates. Within a few days, government workers burned every scrap of the packaging hay in an attempt to protect America’s cows from yet another round of a foreign plague.

When the stones finally made it to the Bronx warehouse, Hearst realized he had yet another administrative catastrophe on his hands—the workers repacked the stones without returning them to their original wooden crates. The crates had departed from Spain with an identifying number and a compass direction on each crate, so that the 10,571 pieces of monastery could be reconstructed.

Now that blueprint was completely, irrevocably gone. Hearst was the overwhelmed owner of what Time magazine christened “the biggest jigsaw puzzle in history.”

St. Bernard de Clairvaux languished in the warehouse for almost 30 years while Hearst plotted his next steps. Putting the monastery back together would require both money and motivation, and by the 1930s, Hearst was running out of both. Now in possession of multiple piecemeal medieval monasteries he had neither the plans nor the resources to rebuild, Hearst began to seek someone—anyone—to take this giant stone burden off his hands. Beginning in 1937, Hearst started liquidating his massive art collection, as the New York Times morbidly noted, “in anticipation for his death.” (Hearst’s death wouldn’t come for another 14 years.) Hearst tasked his art dealers with the work of pawning an art collection that had cost him a cool $40 million (not adjusted for inflation), and included such eccentricities as dozens of full suits of armor, an Egyptian mummy, a pair of Benjamin Franklin’s glasses, and of course, full fledged medieval monasteries. But while the suits of armor flew off the shelves (in many cases almost literally, as some of the Hearst artifact fire sales were held at department stores), a Spanish monastery in 10,000-plus pieces was a much harder sell.

The cloisters at St. Bernard de Clairvaux Church, Miami, as they look today. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

But in 1952, St. Bernard de Clairvaux finally found its buyers. William Edgemon and Raymond Moss, two businessmen from Cincinnati, purchased the cloisters and shipped the crates down the east coast to Port Everglades, at a cost of $60,000. After retrieving the crates from the Florida docks, Edgemon and Moss transported the stones to North Miami Beach; they hired an expert stonemason who spent the next 19 months re-erecting the monastery at a cost of nearly $1.5 million—later assessments would say that the stonemason got the gigantic puzzle “about 90% right.”

The choice of Miami as the location had its own peculiar logic, somewhat tied to the new popularity of central air conditioning. Reasoning that people might eventually get bored of the beach—or, at the very least, that it might occasionally rain—enterprising businessmen opened new tourist attractions, including amusement parks, aquariums and a wax museum around the city. The Ohio entrepreneurs banked on the monastery being beautiful and novel enough (“STEP BACK IN TIME 800 YEARS!”) to draw in some of Miami’s sunburned masses, and thus invested heavily in its reconstruction. (Similar reasoning would bring another medieval monastery to the Bahamas, too.)

The monastery never took off in the way the entrepreneurs hoped. Tourism in Miami began a downward slide in the early 1960s (due to, among other things, unseasonably cool temperatures and growing concern about drugs) and the monastery’s trickle of guests proved insufficient to recoup its enormous start up costs. In 1964, the cloister was saved from demolition when a philanthropist donated $400,000 and gave the property to the local Episcopal diocese. The Episcopalians continued to operate the site as a local attraction, but eliminated the admission fee and outfitted the locale to be a more suitable place for church services. They brought in carpets, found a new altar among Hearst’s still-for-sale possessions, and set up a church day care. The site’s new chaplain told the New York Times in 1964: “We feel we are redeeming this beautiful edifice. It has fallen very far from grace. After centuries of consecration by the prayers of the faithful, it is ignominious for it to be classified as a ‘giant jigsaw puzzle.’”

Miami of the 1950s, and future home to St. Bernard de Clairvaux. (Photo: Florida Memory/flickr)

If the tale of Hearst’s first monastery seemed complicated, his second monastery would prove no easier to unload. In the case of St. Bernard de Clairvaux, Hearst owned the Bronx warehouse, meaning that having the stones sit around wasn’t costing him much. But in San Francisco, Hearst needed to rent 28,000 square feet of warehouse space to house the crates containing Santa Maria de Óvila. With the onset of the Depression, and Hearst at real risk of bankruptcy, the tycoon could no longer afford to hemorrhage money in this manner.

Hearst’s agents began to look for a buyer, but as a Time journalist critically assessed, “(there) was probably not a sane man in the country who would have paid a reasonable price for it in 1939.”

After it became clear to Hearst that he was not going to make any money selling this monastery, he decided to try giving the stones away. In 1941, he proposed donating the stones to the City of San Francisco with the provision that the City would use them to reconstruct the original monastery buildings, and that these would form the main attraction of a Museum of Medieval Arts to be operated by the De Young Museum in Golden Gate Park. De Young administrators and city officials were enthusiastic; the Museum’s director Walter Heil wrote in a letter to Hearst that this was the most thrilling news he had received in his tenure in office. In anticipation for the move, Hearst took the stones out of the warehouse and had the crates placed in Golden Gate Park.

But like all previous plans for the stones, this dream too would prove short-lived. With the outbreak of World War II, municipal planning ground to a halt as government agencies refocused on defense and military operations. Directing energy to building a giant medieval museum also seemed somewhat tone-deaf when the nation was in the middle of a violent international entanglement. One museum board member recalled a heartfelt plea to the city “to reassemble the monastery’s stones at a dire point in the war when courage born of faith—any faith—could be reborn and flower in the lyrically soaring arches of a resurrected Santa Maria de Óvila.” Unfortunately, just three months after Pearl Harbor, Americans were not apt to see parallels between the courage of wartime valor and the “courage” of rebuilding a European cultural site.

Monastery stones in Golden Gate Park, San Francisco. (Photo: Binksternet/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

Any last hope for the museum went (literally) up in smoke, after a series of fires damaged the unattended monastery stones. Between 1941 and 1959, no fewer than five inflagrations tore through the stones. Arson was heavily suspected (though never officially proven), and employees of the museum speculated the fires were related to a vocal faction of San Franciscans who did not want any construction in Golden Gate Park. This was a depressing time for Hearst’s architect, Steilberg, who was still hoping for a grand medieval structure. As Time would later note, “a kind of fatalistic lethargy seems to have settled on the California project.”

The ruins remained in Golden Gate Park until the end of the 20th century, as most people initially involved in the project either passed away or lost interest. The stones became weathered and overgrown with grass and weeds, morphing into the landscape of the park. Among their many new purposes, the stones served as a playground for children, a canvas for graffiti artists, and a site of “meditation and love” for San Francisco’s druid community.

Europeans to American Medieval Building Buyers: Drop Dead

From riots in Spain to scathing op-eds in English papers, Europeans did not let their medieval buildings sail quietly to America. In the face of energetic opposition, it is shocking how successful Americans were at taking these pieces of cultural heritage. Of course, it was sometimes legal for them to do so—barely legal, but often technically legal. England’s series of Ancient Monuments Protection Acts had not defined “ancient” in such a way that encompassed Agecroft Hall and Warwick Priory, Spain did not move to forbid the export of cultural heritage until after Byne had bought his first monastery, and George Grey Barnard famously finished putting his cloisters—The Cloisters—on boats just two days before France’s cultural heritage laws came into effect. However, to understand how Americans kept taking buildings and how Europeans made sense of these thefts, we need to look beyond the formal laws to the complicated and often tragic histories of the medieval buildings themselves.

Often, it came down to one critical question: How much of a building do you need to own to say that you own a building?

For something like the late Gothic chapel from the Chateau d’Herbéville, now at the Detroit Institute of Arts, the answer might be fairly simple. The nobles Jean Bayer de Boppart and his wife, Iseberg decided they wanted one of these private chapels that were all the rage, they hired skilled craftsmen to append it to their family home, and up it went. When antiquities dealer G. T. Demotte came across the building after World War I, he removed the walls, roof, interior stone and wooden elements of the chapel from the rest of the structure—by then mostly ruins—and could market the thing as a late Gothic chapel.

The St. Joan of Arc Chapel, Milwaukee, originally built in the Rhône River Valley in France. (Photo: Emma Stodder)

Something like the monastery of Sant-Miquel-de-Cuixà is a little more complicated. Physically, it’s a mass of different constructions, assembled over time. To a 9th century foundation, the monks added a church in the 10th century that was then refurbished, then consecrated, then overshadowed by a larger church built a few years later, all of it ultimately bolstered by many additional structures in the 11th century that helped to get more foot traffic going past the monastery in the form of pilgrims who donated and spent their way from their homelands as they traveled to Saint James of Compostela. In other places, building programs extended centuries further, into the 1400s. Americans were especially interested in Gothic and Romanesque stone—when Byne took his monasteries out of Spain, he just left the post-1200 material in ruins and in situ.

As far as Hearst was concerned, he owned Santa Maria de Óvila after his years of toil and millions of dollars spent, all culminating in the monastery’s relocation to America. In spite of the building’s epic journey, many in Spain do not realize that it ever left. The remaining buildings were rebuilt on their original site decades later, yielding the extreme oddity of a medieval monastery that is apparently now in two places at once.

While these layered and often confusing histories have today resulted in an alarming metaphysical conundrum, they were very convenient for American buyers in the early 20th century. Plus, from their perspective, they weren’t stealing history—they were doing the structures a favor. Time and war had left many of Europe’s “treasures” in sad shape. In England, religious institutions like that housed at Warwick Priory were dissolved under Henry VIII in the mid-16th century. Practically, that meant that the buildings were stripped of their furnishings and their inhabitants were released from their vows and sent away. In France, the Revolution led in 1790 to the dissolution of all religious orders and the nationalization of all Church property, with devastating consequences for the buildings and their communities (as well as for historians, since many, many archives were destroyed as a result).

What wasn’t destroyed, the state sold to private owners, usually for extremely low sums. One element of The Cloisters was, after 1792, used as a stable, a jail, a weapons foundry, a private residence, a garrison, and a hotel warehouse before locals dismantled the structure to make room for another hotel.

Americans and Europeans both hurled these long histories at one another when, on the one hand, staking a claim to medieval buildings and, on the other, repudiating American theft of cultural heritage. When the U.S. media reported on medieval acquisitions, they often revered American tycoons as heroic preservationists of the past. A 1936 New York Times editorial on The Cloisters praised the “patient [sic] genius” of George Grey Barnard and the “discerning and generous genius” of John D. Rockefeller Jr. in bringing the medieval sites to New York City. Both the media and the buyers of the monasteries were eager to draw connections between American and European history. “Mr. Rockefeller has helped to pay one great debt of our age to the Middle Ages by choosing to repair the Cathedral of Rheims,” opined the Times.

John D. Rockefeller, Jr., c. 1915. (Photo: Library of Congress)

World War II further cemented Americans’ belief that what Europeans had labeled “kidnapping” and “acts of thievery” actually represented actions for the good of humanity. When the Nelson Gallery of Art and Atkins Museum in Kansas City, Missouri, acquired a 13th-century French cloister in 1943, one curator declared its removal from Europe as “a splendid thing,” since now “we have [the elements] in this country where they are safe.”

The European side was just as entrenched. Perhaps the most brutal fight occurred over the purchase of a monastery and a great manor house by Virginians. The back-and-forth, waged through the press of each country, reached comically great heights.

In the summer of 1925, England was up in arms about the impending destruction of Warwick Priory, a group of formerly monastic buildings in the north. A meeting of the House of Commons on the subject exploded, but no political salvation could be found. The city of Warwick came up with ingenious solutions, all of which failed. It offered the buildings free of charge to the bishop of Coventry, but he refused to live so far from his flock. Undeterred, the city tried to turn the old monastery into public housing, but plans quickly fell through.

Then, on September 25, the papers reported the shocking news that Warwick Priory had been sold—to an unnamed American. The building, once visited by Queen Elizabeth I herself, would be transported to the U.S.

Virginia House, from the dismantled Warwick Priory, Warwickshire, England, c. 1929. (Photo: Library of Congress)

At first, news was scarce. Details only emerged a week later, when the AP cleared up “mysterious reports” by identifying the purchasers as Alexander and Virginia Weddell of Richmond, Virginia. They had bought the buildings to recreate another Warwickshire monument: Sulgrave Manor, English home of George Washington’s ancestors. Facing a barrage of criticism that they were stealing a vital piece of English history, the new owners went on the attack, giving interviews far and wide to make the case that they were the best caretakers for the property.

The Weddells developed two now-familiar rhetorical strategies. They immediately pointed out that they were doing Europe a favor by rescuing and restoring neglected treasures. Everything inside the buildings, even the stairs, had already been stripped and re-installed in an English factory. Adding insult to injury, the sale had been publicly announced and no one else had bothered to cough up the money. Alexander Weddell claimed he had never schemed to get his hands on an English home, he just happened upon the announcement when reading the newspaper his sandwich had been wrapped in.

Second, the Weddells explained, with the help of the American media, how Warwick Priory would fit in as well in Virginia as in Warwickshire. Papers on both sides of the Atlantic fixated on the fate of the priory for more than a year, from the first shipment of material from England to the U.S. on November 28, 1926, to breathless reports that the Weddells’ new home was nearing completion on May 8, 1927.

Each report brought with it new details, many of which strained credulity. The New York Times wrote that Virginia Weddell herself was a descendant of George Washington’s family in an article titled “American Buys Warwick Priory As Shrine Here to Washington.” Another paper speculated that Warwick Priory would yield 6,000 to 10,000 tons of brick and stone for the replica from the exact same quarry that had supplied material for Washington’s ancestral home. The Boston Globe’s long profile detailed the centuries of close friendship enjoyed by the Washingtons and the owners of Warwick Priory before the colonists came to America.

The interior of Virginia House, 1929. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Virginia Weddell herself waded into the fantasy of Warwick Priory as not just an English building, but a proto-American one. She reminisced about how the ships sailing with the building materials followed the same trail that the colonists had taken when they came to Virginia, where they built English-style houses of their own. “True, those brave pioneers started from Blackwell, near London; but their little ships, the Sarah Constant, the Godspeed and the Discovery, passed Old Point Comfort, as will my ship; and the Priory is to be unloaded at a point not far removed from the landing place of Captain John Smith.”

While all of this glorification of a new, medieval monument to George Washington was going on, a new scandal was brewing in Britain. On January 25, 1926, the chairman of the Manchester Art Gallery Committee told a meeting of the Ancient Monuments Society that he had received a letter from an American correspondent. The letter asked if it was true that the great manor Agecroft Hall had been purchased and would be dismantled and shipped to America.

It was Warwick Priory all over again. The society’s secretary, John Swarbrick, immediately went to see the purported seller of the house, who confirmed that the rumors were true: A Mr. T.C. Jackson Jr., of Elizabeth, New Jersey, had purchased the hall and it would be moved to New Jersey imminently. Swarbrick warned in an interview that there was a craze for medieval buildings in the U.S., that the same people involved in Warwick Priory were responsible for the sale of Agecroft Hall, and that more purchases of the kind were underway.

Agecroft Hall, in Richmond, Virginia. (Photo: Fopseh/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

Swarbrick was wrong about almost everything, though it was true that the architect Henry G. Moore participated in both purchases. Moore had found the building for Richmond businessman T. C. Williams, Jr., who wanted it for his Virginia—not New Jersey—estate. Williams was enthusiastic not so much about the (non-existent) colonial connections, but about the opportunity to recreate a pre-industrial haven along the lines of the medieval English village. There would be no skyscrapers, no intensity of urban industrial life, nothing but idyllic communities and authentically “Old English” country homes—the aesthetic apparently being a critical component of both the lifestyle and the values it implied.

Two great houses pillaged by Americans in less than six months was too many for the English. In 1926, the Manchester Guardian ran several dozen editorials and letters to the editor decrying the sale and removal of Agecroft Hall. One editorial called for stronger laws to protect British landmarks, calling it “a national loss”: “Warwick Priory is gone. Agecroft Hall is going. No building of decent age and character is safe from the danger of kidnapping.” Another editorial labeled the sale “a raid.” The sale of Agecroft Hall and Warwick Priory even prompted the House of Lords to debate a law forbidding the export of English cultural heritage (opponents weren’t comfortable telling people what they could do with their private property), though the Ancient Monument Protection Act was not strengthened until 1931.

The Elizabethan knot garden at Agecroft Hall. (Photo: Fopseh/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

In spite of all this rancor, the kinds of arguments that the Weddells and Williams made seem to have struck a chord. Agecroft Hall, like Warwick Priory, had been in sad shape when it was purchased by an American. The Industrial Revolution left the hall uninhabitable. Coal pits surrounded the house; a freight railway skirted the buildings. One British writer turned his criticism of the sale inward, calling filthy, despoiled Agecroft Hall “too reproachful a jewel to leave in that ruined landscape.”

Medieval Buildings Home to Roost

Americans did, for the most part, make good on their promises to preserve these sites. By the 21st century, almost all of the medieval buildings brought to America had ended up in museums—some in well-endowed East Coast institutions with entire wings dedicated to medieval art and devoted to “transporting guests back in time to the Middle Ages,” others in small Midwestern galleries, with a handful of medieval pieces thanks to a local bigwig’s fleeting interest in the period. A few, like the Hearst buildings in California and Miami, are slightly more accessible, but are still framed by exhibitions and have a museum-y look-but-don’t-touch air about them for most visitors. The uniformity of the sites today stands in stark contrast to the variety of uses envisioned by those who brought medieval buildings to the U.S., or the experiences of the buildings throughout the 20th century: They were or might have been tourist traps, chapels, swimming pools, museums, private residences, or piles of rubble in warehouses and in parks.

By the late 20th and early 21st centuries, many different communities had become deeply invested in the medieval buildings that by then littered the American landscape. The effect of the historical bricolage sometimes borders on the surreal. Agecroft Hall was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1978 because it reflected the “social and aesthetic ideals of upper-class Virginians in the 1920s,” not so much because of its medieval heritage. The final nomination form noted that it was “unaltered” and in its “original site;” its period “1900-” and significance fell under the “agriculture” and “community planning” categories.

Photograph of the central yard surrounded by the cloisters of the St. Bernard de Clairvaux Church, Miami. (Photo: Rolf Müller/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

There were occasional calls for repatriation of the sites mentioned here to Europe, but the medieval European buildings eventually became too entangled in America to be so easily returned. In 1940, Spanish dictator Francisco Franco demanded the return of the monasteries that Hearst, in his words, stole, but nothing was done. More recent and sustained calls for repatriation of The Cloisters buildings to France faced criticism from no less than the eminent social theorist Jean Baudrillard, who used the medieval buildings in America as a case in his Simulacra and Simulation. Baudrillard thought that by this point “demuseumification [was] nothing but another spiral in artificiality”; The Cloisters were already artificial, returning Sant-Miquel-de-Cuixà to its original site would be even more so “a total simulacrum.” Leaving the cloister in New York “in its simulated environment … fooled no one,” while moving it was a “supplementary subterfuge,” a “retrospective hallucination.”

The retroactive reality Baudrillard described did not come to pass. The buildings continue to have vibrant and multiple lives within American communities today. At two sites that we visited, Ancient Spanish Monastery in Miami, and the Abbey of New Clairvaux in Vina, California, extensive preservation efforts were matched with a variety of contemporary roles. In these transposed places, community members meet, families pray, and people hold weddings, funerals, and, of course, yoga classes.

In the 1970s, the stones of Santa Maria de Óvila, at long last, caught a break. A Cistercian monk named Thomas X. Davis heard about the remains of the monastery and became interested in bringing them to his abbey, about three hours north of San Francisco in the small town of Vina, California. His timing overlapped fortuitously with the research of Dr. Margaret Burke, an art historian who received funding from the Hearst Foundation to study the stones. Burke began categorizing the stones, determining what part of the monastery they would have originally belonged to, and, in 1984, offered the city a comprehensive report of each stone, its condition, and whether it could be preserved. Meanwhile, the monks continued requesting that the city take their proposal seriously. After extensive discussions between the monks, the De Young Museum, and the city, the museum’s trustees agreed to relinquish control of the stones in 1992. Two years later, the stones began their journey to Vina—but even this short trip had its hurdles. Father Davis reported that on several occasions, individuals who opposed the stones leaving San Francisco pushed the stones off their pallets during the night, leaving workers to reload the trucks in the morning.

View from within the 800-year-old chapter house brought from Santa Maria de Óvila, now at the Abbey of New Clairvaux in Vina CA. (Photo: Frank Schulenburg/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

Though the monks took the majority of the stones to Vina, some remnants stayed behind in Golden Gate Park. Debates about what constituted an “appropriate use” for the leftover stones continued into the 21st century. A 2001 investigation into the stones in SF Weekly noted that though most of the materials had gone to Vina, there had been an “odd truce” negotiated among the park, the De Young museum, and the monastery regarding the remaining abbey stones. For nearly 50 years, the gardeners of Golden Gate Park had access to their own private quarry of ancient limestone, which they could use whenever the park needed new retaining walls or landscape decoration. For instance, some of the stones became part of a decorative rock wall at the Strybing Arboretum library. “We think the wall that we constructed outside the library is the most sensitive use yet,” said Scott Medbury, a park employee. What one art historian labeled “the worst act of desecration of a medieval monument during the last half-century,” the city lauded as a practical and thoughtful use for the materials that had sat abandoned for the majority of the 20th century.

So what to make of the current state of these medieval buildings-as-museums? Certainly, good preservation practices will ensure a long life for the aged stones. But there is also a sense in which the medieval buildings have been deadened by their modern lives as display pieces. Old material given life through new use, called spolia, is, after all, very medieval. The altar at Sant-Miquel-de-Cuixà, the very heart of the religious life of the monastery, was itself made of part of a Roman column. Reuse did not erase the old meaning, it augmented the new one, though of course that column did not mean the same thing to a medieval person as to a Roman, nor is a modern library wall the same thing as a medieval one. Even now, many San Franciscans share memories of crawling over the medieval stones in their park as children, of the blocks as meeting places and landmarks. On the other hand, maybe the distinction between the museumified version of these places and their “freer” state is not so different, since New Yorkers are equally eager to describe their memories of childhood trips to The Cloisters.

But even in Vina, at a monastery that exudes austerity and age, traces of 2015 slip through. The monks, concerned about the challenges of recruiting young men to the brotherhood, have taken to Instagram (@monksofvina), where they update their followers on paintings in progress, their 3:30 a.m. prayer meetings, and the status of the harvest. Common hashtags include #monks, #cistercian, #monastic, and #monkslife. In Miami, too, the medieval buildings live modern lives. The site’s cloistered halls have become the backdrop for such pop culture gems as the spectacular flop of a 2011 Charlie’s Angels TV reboot, a scene in the 2012 film Rock of Ages in which Catherine Zeta Jones sings “Hit Me With Your Best Shot,” and Rick Ross’s music video for “Ten Jesus Pieces.”

But for every Victoria’s Secret catalog photo shoot, the Miami monastery also sees a steady flow of more ordinary life events—the monastery receives 50,000 visitors a year, and hosts 200 weddings annually. People are free to wander throughout the monastery when it isn’t being used for pilates or baptisms. The medieval history of the site isn’t absent from these events, though; it’s often omnipresent: one woman at the monastery enthusiastically told us that she had had three of her children baptized at the monastery because she was so impressed with the site’s history and the effort to move it from Spain to America. In typical Miami fashion, the conspicuous and the commonplace often careen wildly into one another—the priest of the monastery’s Episcopalian congregation mentioned that in the first wedding he officiated at the monastery he noticed a familiar-looking bridesmaid—Britney Spears. It’s hard to imagine a more American fate for these medieval stones.

Medieval America received funding from History in Action, an American Historical Association/Andrew W. Mellon Foundation initiative at Columbia University.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook