India’s Mini-Craze for Bicycling Around the World

In the 1920s and 1930s, a dozen adventurous young riders went on the ultimate journey.

In 2017, Anoop Babani, Goa-based former journalist, was recuperating from a cycling accident when he encountered a book from 1931, With Cyclists Around the World, written by three Indians who, in the days before widespread paved roads and satellite communications, had biked around the world.

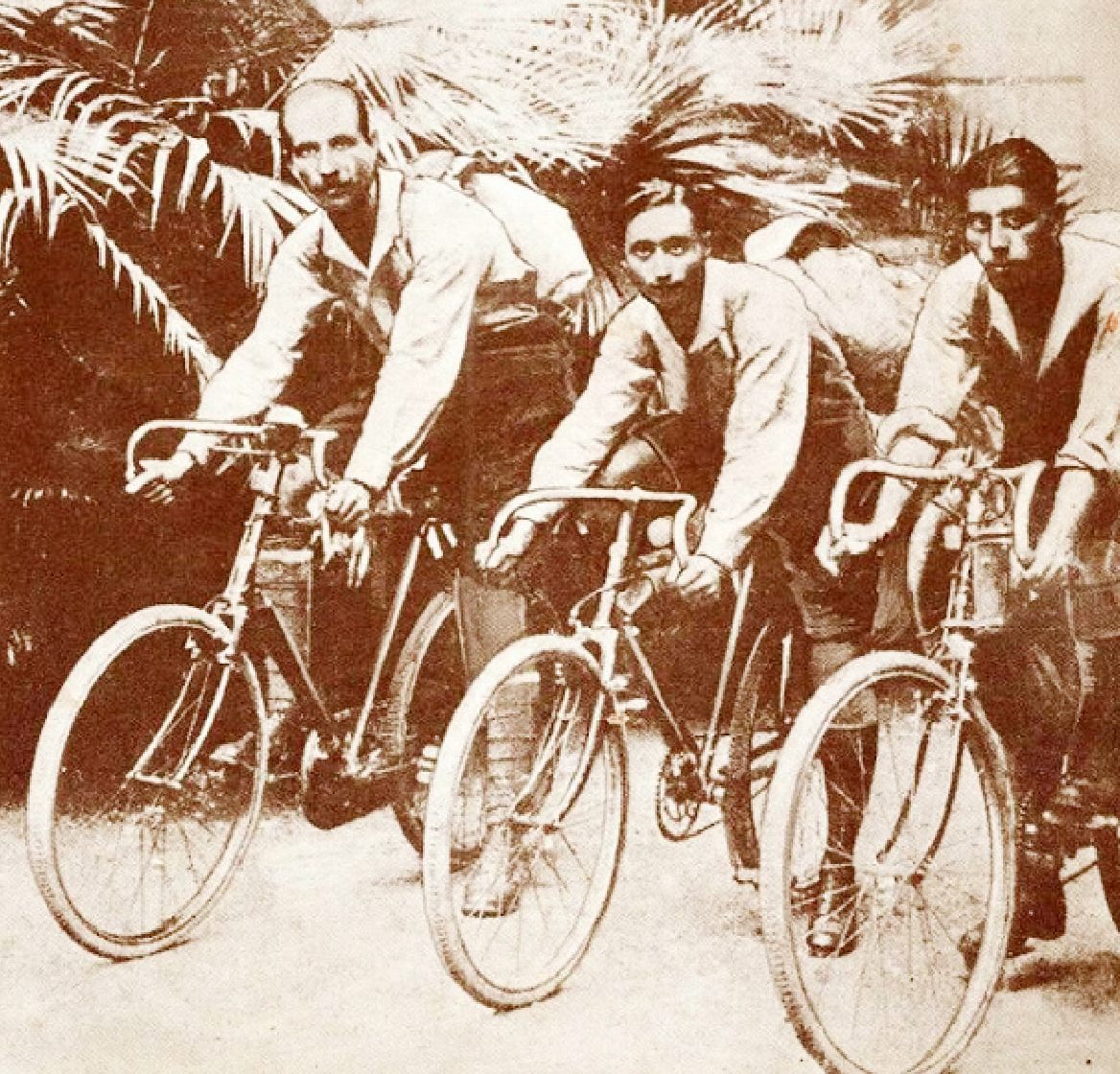

“A new China has been born in the world,” they wrote prophetically of one of their destinations. “Few see her; but those who do see, realize how she will affect world’s course and shape world’s history.” The cyclists—Adi Hakim, Jal Bapasola, and Rustom Bhumgara—chronicled their entire, unusual, four-and-a-half-year expedition. In early 20th-century India, cycling was for commuting. It was never considered a way to see the world.

“They were much more than mere cyclists,” says Babani who, along with his wife, artist-writer and fellow avid cyclist Savia Viegas, began to research the expedition in greater depth. They found how the cyclists returned to tell India more about a changing world—and inspire others to take similar journeys: four more such global expeditions, spanning 1923 to 1942, involving six more cyclists. All who partook in the small-scale craze were from the Parsi community of Mumbai (then Bombay).

Babani and Viegas collected archival information, interviewed family members, and found photographs. Their work resulted in a photo exhibition, Our Saddles, Our Butts, Their World, and has now taken the form of a book, The Bicycle Diaries: Indian Cyclists and Their Incredible Journeys Around the World. The result is a glimpse of a world between wars, in the midst of vast social and political change. It also landed the adventuring cyclists in jail a few times.

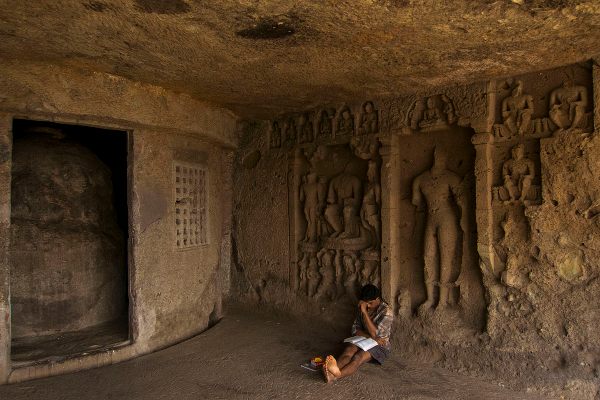

Adi Hakim was a member of the Bombay Weightlifting Club with a knack for outdoor activities. In The Bicycle Diaries, his granddaughter Jasmine Marshall says, “‘Nothing is impossible,’ he would always tell me. A passion, I am sure, shared by all his bicycle mates.” There were six of those, including Bapasola, Bhumgara, and three others who started the grand expedition but did not complete it. It’s not completely clear what inspired these young Parsis (an ethnoreligious group that practices Zoroastrianism) and the ones who followed them, but Babani believes it was their way of participating in India’s freedom struggle. “Instead of waving flags and joining demonstrations, they chose to pedal on a perilous path,” he says, “to paint for the world a true picture of India that would depict the glorious civilization, culture, and architecture of our native land.”

The expedition departed Mumbai in October 15, 1923. By the time they returned in March 1928, they had been to 27 countries and pedaled more than 40,000 miles—through Punjab, Balochistan, the Middle East, Europe, United States, Japan, and Southeast Asia. They encountered dense forests, swamps, and the terrible solitude of the Alps.

Each man rode a Royal Benson bicycle and carried just a British passport, some clothes and medicine, bicycle repair tools, a used compass, a world map, and Rs. 2,000—about $27. But they also brought skills to the trip. Hakim was the chronicler, Bhumgara a trained automobile mechanic known to perform circus-like acrobatics, and Bapasola the map reader. They spent the first three months cycling through India, and then into what is now Iran, where, to earn money, Bhumgara pulled a car with five passengers down the road with his teeth. From there they went to Baghdad, and across the Syrian-Mesopotamian desert, which they crossed in 23 days. Family members describe this as the worst part of their journey—and a phenomenal achievement.

Lovji Hakim, the third of Hakim’s seven sons, says in the book that at one point his father had them all say their last prayers. “Fortunately, some Bedouins found them,” he says. “Every time my father narrated this story to me, he would suddenly go silent and humbled that he was alive.”

“Our lives, we were told, were in grave danger from their predatory excursions,” they wrote of the people who helped them get through the desert. “Instead, throughout our journey we found the Bedouins more a friend than an enemy.”

A sea voyage then took them from Alexandria in Egypt to Brindisi, Italy. In Rome, they got an autograph from then–Prime Minister Benito Mussolini, and at the Vatican they had an audience with Pope Pius XI. Europe at the time was still deeply scarred by World War I: poverty, bad roads, and unhygienic conditions. In Rome they were mistaken for German spies and spent a night behind bars. But the Prime Minister’s autograph and a news report about their journey in a Roman newspaper backed their otherwise far-fetched story.

After raising some money in Europe, they sailed with their bicycles to New York, which they found “bewitching.” They spent two weeks among the skyscrapers, traffic, and flappers. One of their initial riding companions, Gustad Hathiram, decided to stay in the United States. (He became an auto mechanic in Florida, and died in 1973.)

The remaining cyclists spent the next five months pedaling across the United States, where they were warmly received by hundreds of Indians studying in American universities. In Detroit, they briefly worked for the Ford Motor Company, presumably on the assembly line for the iconic Model T.

They were particularly in awe of American roads. “It was for the first time in our journey that we could ride 100 miles a day consecutively for five days,” they wrote of the trip from Boston to Buffalo. They found other parts of the American experience disheartening, such as the rude and insulting immigration authorities. “The immigrant is at best tolerated and viewed with suspicion,” they wrote. They were equally appalled by the “racial discrimination of the most demeaning character which is observed in railway trains, at railway stations, in tramcars, in hotels, and in places of amusements.” They continued, “India to them is a semi-barbarous country inhabited by black figures, mystics, magicians and infested with snakes and tigers.”

From San Francisco they sailed to Japan in November 1925. From there they went to the mainland and became the first to cycle across the “Hermit Kingdom” of Korea in winter. This brought them into China, pulsing with violent political change. Rifles were pointed at their heads when they were suspected of being spies. In Indochina (present-day Vietnam), they were furious about immigration rules and how Indians were treated by the French colonial government. Bapasola wrote an article about it for a local newspaper, at which point they were arrested—again—on charges of “bringing into hatred and the contempt of (French) government of Indo-China!” they wrote. They were only released after the intervention by Siagon’s Governor, Maurice Antoine Francois Monguillot, a sportsman himself.

Finally, in March 1928, they returned to Mumbai and a rousing reception. Along the way they had received warm welcomes, been awarded 26 medals, delivered public lectures, and collected 146 autographs: kings, the Pope, prime ministers, presidents, industrialists, mayors—even Zhang Zuolin, the Warlord of Manchuria.

Their efforts inspired others. In January 1924, sports journalist Framroze Davar went on a solo expedition. He picked up a traveling partner in Vienna, Gustav Sztavjanik, and the two cycled together for seven years, across 52 countries. “Theirs was the toughest and most adventurous journey,” says Babani: West Africa, the Sahara, the Amazon, the Andes.

In April 1933, another trio from Mumbai—Kaikee Kharas, Rustam Ghandhi, and Rutton Shroff—began a nine-year expedition of more than 50,000 miles. “They were the first cyclists ever to cycle across iron-curtained Afghanistan,” says Babani. They were present at the historic Nuremberg Nazi Party rally addressed by Adolf Hitler, and were the first to cycle across Australia, New Zealand, and Indonesia. Two more solo expeditions followed. Eighteen-year-old Jamshed Mody left in May 1934, and went 30,000 miles in three years. Manek Vajifdar departed the same month, but ended his journey in London four years later due to international conflicts. All told, the expeditions resulted in a half-dozen more books, and opened up the world to Indians back home who might never have had a chance to see it.

Upon their return, the original three cyclists were lauded, but not formally recognized by the British government of India, which may be one reason their efforts have not been celebrated more. “At that time cycling tourism was a completely different ball game. It was an upper-class pursuit initiated and introduced predominantly by American and European cyclists in early 20th century,” says Babani. “A handful of Indian cyclists were impressed by it and took to it. Hence, it was imperative for the then-ruling British Empire to recognize their deeds. Since this did not happen, the cyclists and their journeys were totally forgotten until recently.”

After basking in some glory, all three cyclists returned to regular life. Hakim had a long career in the oil industry. Bhumgara joined the independence movement, assisted the Indian National Congress, and worked in the auto industry. Bapasola joined a steel company.

Babani and Viegas are now pushing for a museum and public monuments to honor all the cyclists. And Babani says that he’s seen a resurgent interest in recreational cycling in India: megastores selling premium bikes, an explosion in local cycling clubs, new endurance cycling events. But cycling around the world? That remains an ultimate challenge. “Their achievements and adventurous spirit have left an indelible imprint on the country,” Babani says, “as well as a source of inspiration.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook