How Radar Is Helping Track Down Lost Indigenous Gravesites

It’s getting easier to find potential remains non-invasively—but that’s just one step in a long and painful process.

This piece was originally published in Undark and appears here as part of our Climate Desk collaboration.

Over four days last May, members of the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc, a First Nations community in the interior of British Columbia, oversaw a site survey of around two acres of land surrounding the province’s former Kamloops Indian Residential School.

Using an electromagnetic technology called ground penetrating radar (GPR), an archaeology professor charted what appeared to be the grave shafts of 215 children lying below the ground. The technology furthered the long-held suspicion that there were remains of missing children hidden on the land of the school. Former students at the school recall being woken at night to dig graves, for example, and a child’s rib bone and a juvenile tooth had surfaced in the area. Kamloops was the largest of the 139 government-sanctioned residential schools in the country that operated between the 1880s and 1990s. The facilities separated 150,000 Indigenous children from their families and educated them in English or French while banning native languages and indoctrinating them into Christianity.

“We had a knowing in our community that we were able to verify,” Rosanne Casimir, the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc chief, stated in a press release after the graves were discovered. “To our knowledge, these missing children are undocumented deaths,” she said. “Some were as young as three years old.”

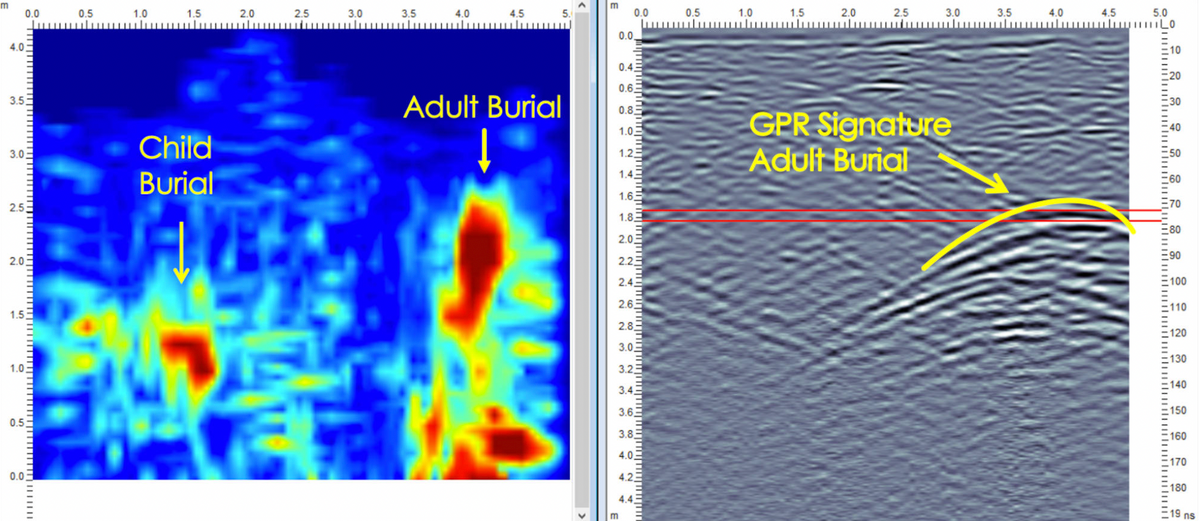

At the time, few people in Canada had heard of GPR. This century-old technology emits a high-frequency pulse into the ground. When the pulse is reflected back to the surface, the elapsed time gets fed into computer software, offering a visual representation of what’s under the earth. Utility companies and archaeologists have been using it for decades, but more recently it has been used to unearth Canada’s bleak history surrounding its residential schools.

So far, Indigenous groups across Canada have used GPR—along with other site survey technologies such as magnetometry and drones—to identify more than 1,800 possible graves at former residential schools, confirming an open secret.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, established as part of a settlement agreement between residential school survivors and the Canadian government in 2008 to document the history and impact of the school system, has identified 3,200 child deaths at the schools. But in 2009, its request for $1.5 million Canadian dollars (about $1.35 million U.S dollars at the time) to hunt for unmarked graves was turned down by the Canadian federal government. In 2020, though, the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc secured a Canadian Heritage grant to fund its search, taking advantage of increasingly affordable and accurate GPR technology.

“The depth at which you can get a signal from and the quality of the data that it produces has increased rapidly over, let’s say, the last 10 years,” said David Markus, an assistant professor of archaeology at Clemson University in South Carolina.

The Kamloops discovery kindled a fiery national conversation about residential schools, and last August the Canadian government announced 250 million Canadian dollars (around $200 million U.S dollars) in support for residential school grave searches and community emotional support.

The news also intensified interest in the United States in the use of GPR and other non-invasive technologies at its own Indian boarding schools, and to help locate hidden graveyards of Native Americans and Black people. Last June, citing the Kamloops news, U.S. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland—a member of the Laguna Pueblo tribe in New Mexico whose grandparents were sent to boarding schools as children—announced the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative, which seeks to create an inventory of schools, discover burial sites, and identify the names and tribal affiliations of children who went to these schools.

Such a process is currently underway at the former Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania. In 2017, a GPR survey confirmed which grave markers in its cemeteries likely corresponded to a burial, and discovered 55 other underground anomalies that needed further investigation. Since then, the U.S. Department of the Army, which owns the property, has exhumed the remains of at least 23 children and returned them to their home communities.

Even with the advances in GPR and other tools, however, the public can misunderstand what the equipment actually reveals. Major media outlets have published headlines stating that people are finding “bodies” in Canada. And according to Marsha Small, who is doing her Ph.D. at Montana State University and has been searching for burial sites at the Chemawa Cemetery near Salem, Oregon, on and off for nearly a decade, people often mistakenly think of GPR as a magic tool that can help uncover bodies and burial sites, when often what’s being detected are tree roots and other masses.

“All it’s going to give you is pixelated images of difference in soil composition — that’s it,” says Markus. “When you’re doing ground penetrating radar, there’s this misconception from some quarters of the general population that we can scan the ground and magically we’re going to see a skull or a femur or whatever.”

To fully identify graves, remains, and identities, researchers must also gather records, collect oral histories, and possibly disinter bodies—and it’s not clear yet if communities will want to take the final painful step.

“Everyone is up in arms and wants answers yesterday,” says Eldon Yellowhorn, an Indigenous studies professor at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia. For communities with children who died at Kamloops and at other schools with unmarked graves, technology serves as just an early step: Only years of painful work and substantial funding will help the secretly buried find a semblance of home. Says Yellowhorn: “Let’s make a 20-year plan or a 30-year plan. [It’s] not going to happen overnight.”

Before the advent of GPR, you often had to grab a shovel or use other basic technologies to locate a possible unmarked grave. “Not everybody likes you poking holes in the cemetery,” says Markus. As a result, there was little people could do when they suspected hidden burials.

Then accessible GPR emerged. Invented around 1910, just six years after radar technology itself, GPR was initially used in the late 1920s to measure the thickness of glaciers, then by the military to locate underground tunnels. In recent decades, utility companies have used GPR to look for underground wires and pipes. Over time, the technology became more finely tuned and affordable, and archaeologists have become skilled at using GPR to locate buried artifacts. Today, the cheapest devices sell for around $14,000, and numerous private companies offer survey services.

Results from a GPR survey are displayed on a computer showing a signal to indicate soil disruptions. “Not every hyperbola is a burial or a grave—there’s tree roots, there’s masses, and other things in the substrate,” Small says. She notes that it takes years of training to operate GPR equipment and interpret the results. “I’ve just barely started my journey even though I’ve been immersed in it for some time.”

Small and others also employ magnetometers, handheld instruments often used by engineers and archaeologists to monitor the magnetic field of a given location. Magnetic readings of topsoil are different than those of subsoil, so detecting changes can indicate previous digging. But magnetometers must be held at a steady distance from the ground while walking, a process that requires a deft touch.

GPR equipment, in contrast, gets mounted on something that looks like a lawn mower or baby carriage, and gets rolled over the ground. In her work, Small depends on both technologies to help sort through tree roots, different soil types, and moisture content.

Andrew Martindale, a professor of archaeology at the University of British Columbia, says there are 23 variables identified by GPR that can indicate underground graves, but not every variable is present in every grave shaft. “Unmarked graves are in various contexts,” says Martindale, who has worked with the Musqueam Indian Band in Vancouver, British Columbia. “The technology may not work to the same degree in all places.”

In many cases, cemeteries are placed in areas where the soil is easy to dig, and GPR can produce clear readings. But “[the] residential school landscape includes clandestine burials,” Martindale says, and these locations can prove trickier.

When the technology detects anomalies outlining a rectangle in an east-west orientation, that may be a grave, since Christians usually bury people facing east. Even secret burials at residential schools, which were often church-run, would be orchestrated by staff and follow this custom, although some unofficial burials may not have this orientation. The size of the disturbance can suggest if the buried could be an adult or a child. But a site survey alone can’t distinguish between an abandoned dig and an actual grave; it can’t reveal bodies or bones, and it can miss graves or overestimate them. If there’s an area of earth that has been disturbed, “it’ll tell you the edges of that disturbance,” said Yellowhorn. “It won’t tell you anything beyond that.”

Yellowhorn, who is part of a collaborative effort led by the Sioux Valley Dakota Nation and supported by researchers at three Canadian universities to conduct site surveys at the 600-acre Brandon Indian Residential School in Manitoba, uses multiple technologies to get more accurate results, sometimes starting with a controlled burn of a suspected graveyard depending on the location. “Vegetation can obscure a lot of what’s there, ” he said.

Yellowhorn also uses drones to take images of the land at different times of the day, which can reveal swales or other surface inconsistencies that could indicate previous digging. He carries out burns when the vegetation is dry, including in the fall, and then observes how the snow settles and melts by spring. After that, he will often use both GPR and a magnetometer.

Those buried in graves that are unmarked, uninscribed, or indicated with an ephemeral object, such as a piece of wood, often come from disenfranchised communities. Decades later, their ancestors often lack the rights to the burial site, and site survey technology cannot be brought in without access to the land.

In the U.S., no one even knows how many boarding schools existed. The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, formed in 2012 to understand and address the trauma these schools caused, estimates there were 367 in 29 states, with some still in operation today.

Residential schools for Indigenous children in Canada were government-sponsored schools run by churches, and some of their land has been sold off to private individuals who were often not Indigenous themselves. In Brandon, Yellowhorn says, one plot his team wants to search is now part of a trailer park, where one of the cemeteries was located. “That’s something we don’t have any control over,” he said.

The situation is grim for Black cemeteries in the U.S. as well. As America expanded and developed more highways and suburbs, they “were allowed to pave over and build over cemeteries, Black cemeteries,” says Kami Fletcher, an associate professor of history at Albright College in Reading, Pennsylvania.

The African-American Burial Grounds Network Act was introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives in 2019 and is working its way through Congress. If passed, it would direct the Department of Interior to set up a network within the National Park Service to help discover, record, and preserve long-ignored cemeteries and graves. Fletcher says widespread support for uncovering and respecting Black graves signals an important change. “Honestly, it really will do a lot because it brings attention to want to study these places,” she said.

A related bill that “directs the National Park Service (NPS) to conduct a study of ways to identify, interpret, preserve, and record unmarked, previously abandoned, underserved, or other burial grounds relating to the historic African American experience” passed the Senate in late 2020.

Using technology to find unmarked graves can have profound emotional consequences for affected communities. “You can’t just show up with a bunch of gear and push it around and not think that you’re going to have an impact on peoples’ lives,” says Martindale. He says GPR research at residential schools used to be run by universities before some communities began hiring professional firms to do the work.

The preferred model is First Nations themselves developing capacity, says Martindale. Across Canada, many Indigenous groups are acquiring their own site survey equipment, learning how to use it, and leading their own searches.

Small says she’s seldom the most technically skilled person on a survey site, but has a valuable role in bringing in people who know the local tribal customs and language. “I know that as a Cheyenne person that I am more linked to these people, to the children in the cemetery than a non-Native is,” she says.

The Canadian Archaeological Association working group on investigating unmarked graves has outlined a 10-step process for conducting this research. While the order of the steps is up to each community, the first step mentioned recommends community-based work that encourages Indigenous people to lead the effort in finding missing children and includes training people to use site survey technologies. Another step involves offering spiritual and mental health support for the communities. “Before you bring the gear out and start surveying, physically looking for unmarked graves, there’s a lot of things that need to be taken into account,” says Martindale, who is a member of the working group.

Another step, conducting archival research, comes with its own challenges. According to The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, one-third of children who died at residential schools did not have their names recorded upon their death, about one-quarter did not have their gender noted, and one-half had no cause of death cited. While Canada’s federal government signed a memorandum of understanding in early 2022 to release residential school records, that won’t offer a complete picture. Many school records still have not been released by religious groups, including the Catholic Church—and the government says privacy issues can complicate what may be shared.

Yellowhorn and his team in Brandon have identified the names of more than 100 children they suspect may have died at the site of the school. “We ferret through every kind of nook and cranny where we can find any kind of information,” he says, including archival records and oral histories.

The final stage of the process—deciding whether or not to disinter graves—is among the most difficult, and for the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc, still years away: Last year’s GPR survey covered just two acres of the 160-acre site, and its archival research efforts have been stymied by a lack of access to school records held by the federal government and the religious order that ran the school—although the group has committed to handing these over.

As for Yellowhorn, whose research team is still in the early stages of site work in Brandon, he remains optimistic despite the obstacles posed by finances, politics, public perceptions, and the ongoing pandemic. “[It’s] all very new and very raw for people,” he says. Moving forward will involve “finding ways to deal with this, find solace in the work, and recognize that there are things we can do, we’re not powerless here,” and that “knowledge is power.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook