Inside the Angola Prison Hobbycraft Sale, Where Inmates Sell their Creations

Art on display at Louisiana State Penitantary’s hobbycraft sale. (Photo: Courtesy The Angolite)

Chances are, you’ve heard of Angola, The Louisiana State Penitentiary. It’s the largest maximum security prison in the United States, and an Angola reference is a fixture in any film or television series based in the south, from True Detective to No Country for Old Men. Sprawling across 8,000 acres of farmland–once a plantation–it’s named after the country in southern Africa where the former slaves that worked on its land came from. And, on one weekend in April and on every Sunday in October, it hosts the Angola Prison Rodeo, the longest continually-running prison rodeo in the country.

Thousands of visitors enter the prison complex to see the show and, last year, I was among them. However, bucking broncos don’t interest me; I was there for the “Inmate Hobbycraft Sale,” which runs alongside the rodeo. After a bag search more thorough than any I’ve ever experienced at the hands of the TSA, and a solemn promise to a security officer that I would not take photos, I entered the prison complex to peruse the wares. They were proudly arranged atop rows of tables; the shopping experience was complemented by a soundtrack of thrashing hooves and the roar of the rodeo crowd.

The variety of items for sale was astounding (even more so considering the myriad limitations inherent to creating art while incarcerated), the talent and expertise of the inmate artists even more so. In just one aisle, I saw a hand-carved bureau; a cow skull garnished so beautifully it seemed plucked from Georgia O’Keefe’s canvas; a Lilliputian metal motorcycle; a pair of ornate guitars constructed from paper and plastic bags; and a stunning, still-life pastel of gardenias, care of a genial, bespectacled “lifer.” While hesitant to give his name or get into a sweeping conversation about his “craft,” the artist mentioned that he derives 100 percent of the inspiration for his art from photographs sent to him by family and friends.

The entrance to Louisiana State Penitentiary, also known as ‘Angola’. (Photo: msppmoore - Angola Prison/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 2.0)

Some inmate artists were there in the yard selling their works that day, but others were still in lock up. At Angola, minimum and medium security prisoners are given the privilege of creating and selling their art at the Hobbycraft Sale, but you won’t find maximum security inmates mingling with the public.

After I left the fair, I found myself wanting to know more about the inmates creating these intriguing artworks. Since May, I’ve been in touch with several of Angola’s artists via Jpay as well as snail mail, and was able to remotely interview them about their work. Jpay is essentially Facebook for prisoners. You can look up inmates by their Department of Corrections (DOC) number, and pay for virtual “stamps” to send them emails, e-cards and pictures, all of which are monitored by their institution. At Angola, prisoners do not have access to the internet, so Jpay is the sole way to communicate electronically with them.

“I get engrossed in a painting and hours pass without my being aware,” Angola artist Emerson Simmons writes me on Jpay. Incarcerated as a teenager, Simmons, 38, has spent more than half of his life behind bars. His mother is an artist, and taught him how to sketch basic figures, and how to see the beauty in all art. “I call on those lessons every time I paint,” Simmons says. He cites the disruptive penitentiary environment as one of his largest artistic hurdles: “Prison is typically a loud place,” he explains. “People are always talking, wanting to be heard—having to stop for all of the distractions causes your ‘process’ to slip.” Above all, Simmons is thankful for the ability to express himself. “I enjoy the release, and wish I would have begun earlier in life.”

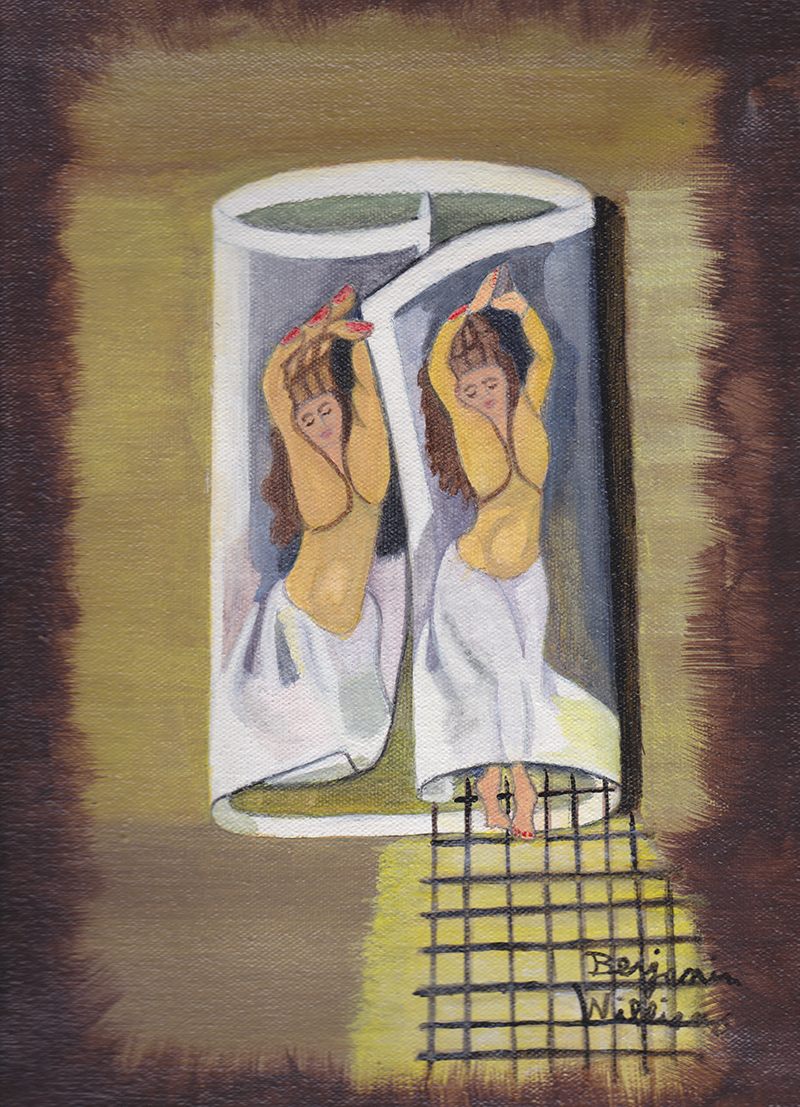

A painting by Benjamin Williams. (Photo: Courtesy Benjamin Williams)

Benjamin Williams, a 56-year-old who creates surrealist paintings, also tells me that painting is relaxing, enabling him “zone out in a place away from prison.” Drawing his inspiration from “beautiful things, life in prison and poetry,” Williams insists that creating art in prison “isn’t a big challenge, so long as you’re determined to do it.” All the artists in Angola work in the “hobbyshop,” where materials are plentiful, so long as “you have your own money to send out for them,” as Williams puts it.

Joseph Woods is a 59-year-old leather craftsman who sells wallets and other accessories at the rodeo. He confirms Williams’ report on the way art creation works at Angola, and expanded on the obstacles inmate artists face. “Time and space [are an issue],” he says, along with “security problems,” which force the hobbyshop to close.

Since Angola inmate artists only have two opportunities a year to sell their work, and much of that money typically goes to buying more supplies, funds for necessities can be scarce. “Art feels like an expression—and a job,” Woods admits. Yet art is also an invaluable boon to his life behind bars. For subject matter, Woods relies on memories of wildlife and nature, as well as recollections of the best moments in his life. “All of my art comes from a positive place,” he says.

The hobbycraft sale is run alongside the Angola Prison Rodeo. (Photo: Courtesy The Angolite)

Angola doesn’t have an art program per se, explains Kerry Myers, editor-in-chief of the award-winning, inmate-run magazine, The Angolite. Still, “Art is encouraged as a productive way of using time,” Myers, who is an inmate, tells me. “There is a competition twice each year on the first day of the rodeo, for artists and craftsmen to enter their creations in any number of categories—paintings of different medium, metalwork, woodwork and carving, jewelry, leather, glass etching, wood-burning and more.”

Angola artists are concerned about the sale of their art, and rightly so, says Myers. “Often it is how they support themselves and also help their families.” Myers helps support himself by selling his handmade custom pens, but his passion lies in writing and photography. “I miss creative photography and cannot wait to reawaken that part of me again,” he says.

“Where there’s a will, there’s a way,” declares Dennis Sobin, director of Safe Streets Arts Foundation, an organization supporting inmate artists. Sobin, a writer and producer, speaks from experience: he is a former inmate.

Sometimes, he says, the lack of distractions in prison can even benefit the art. “I was in solitary for six months,” says Sobin, “and I actually learned how to read music there. Even though I had no instruments, I visualized the whole thing, the whole system for sheet music, all in my head.” Equating this process to that of a professional golfer mentally envisioning his swing to perfect it, Sobin notes that by the time he rejoined the general prison population, his technique had worked. “I got out of solitary and said, ‘I have a system for reading music, it’s in my head. Give me some sheet music.’ And I played it!… It was miraculous.”

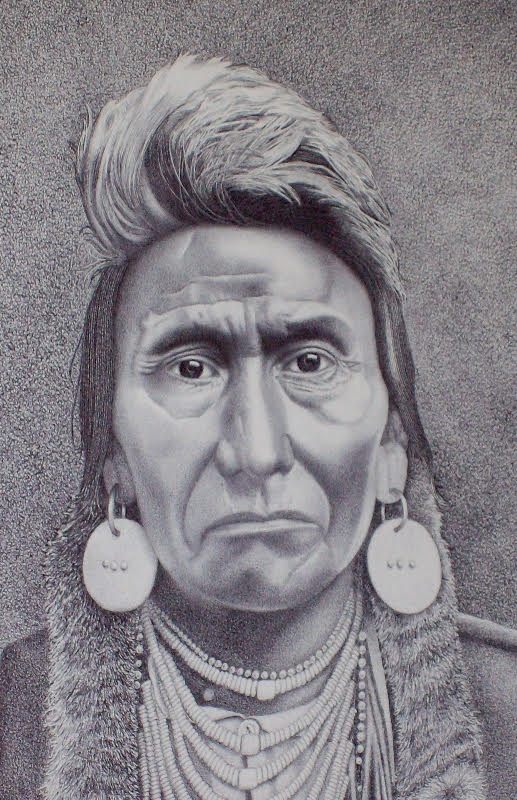

A drawing by inmate Frederick Thompson. He used the stippling method to make his drawings, taking him about 40 hours each. (Photo: Courtesy Safe Streets Art Foundation)

In addition to selling and exhibiting the art of imprisoned artists, Safe Streets also provides these artists with critiques, arts supplies and instruments, and mentors. Or, as Sobin puts it: “We provide an escape from prison. We allow people to create their own world through their writing, through their art…and then the prison walls disappear,” he adds.

There are 5,000 jails and prisons in this country, and the availability of art programs is different at each one. “Some will be very liberal, making music instruments, supplies, canvas, anything, available to inmates to keep them occupied and out of trouble, and to give them something positive to do,” Sobin remarks. “Other prisons are extremely conservative and give nothing but a pencil and a piece of paper. And the only reason they do that is because, legally, they have to provide some way for inmates to communicate to the courts.”

Often, incarcerated artists have to get creative when it comes to acquiring supplies. One found his canvases in an unlikely place: the maintenance shop. According to Sobin, “He discovered that the various parts that had come in were wrapped in canvas and, while the insides of the canvas were dirty, the outsides could be—and have been—put to use for artistic work.”

Sobin has seen fascinating artwork emerge from even the most stringent environments. “Some of our most beautiful pieces are in pen and pencil, done on 8.5-by-11-inch paper, and, at times, on the scraps or on the backs of grievance forms—any kind of paper they can get,” he says. “If you have nothing more than a pencil and paper, you can write books, you can make art, you can create whatever you want.”

A first place entry on display at the hobbycraft sale. (Photo: Courtesy The Angolite)

After an afternoon spent wandering through the Inmate Hobbycraft Sale, chatting with the “vendors” and buying enough art to fill a suitcase, I was later struck by the normalcy of it all. Apart from the barbed wire and the bizarre rigmarole of getting inside, the whole thing was extremely similar to the countless art fairs and gallery openings I’ve attended over the years in New York. In that setting, I wasn’t mingling with prisoners—I was talking with artists about their work. When I mention this to Sobin, his expression brightens.

“What we try to do is show, through their art and writing, the humanity and feelings of men and women in prison and let the public know they are caging fellow, talented human beings here who have real feelings and real abilities,” he says. His goal at Safe Streets is to encourage the public to think twice about harsh sentences and about denying alternatives to incarceration.

“Art makes us open our eyes in a way that nothing else can,” Sobin says. “You can go to a lecture from the ACLU about what’s being done wrong with our criminal justice system, but everyone—conservatives, liberals—is attracted to art. If you can get people to view art, you’ll gain audiences that you wouldn’t be able reach in any other way.”

If you’d like to get in touch with any of the inmate artists featured here, whether to commission a piece or just to say hello, send an email to [email protected] with the artist’s name and a link to this article.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook