Inside the Bizarre, Racist Scheme to Import Siberian Workers to Hawaii in 1909

The laborers were to work in sugarcane fields, and also render the islands less Asian.

A photo from a passport application for a Russian couple in Hawaii, c. 1917. (Photo: Russian Collection, Hamilton Library, University of Hawaii at Manoa)

On October 21, 1909, a crowd of curious onlookers gathered in Honolulu Harbor to catch a glimpse of Hawaii’s future: A cavalcade of Siberians, 200 of them, dressed in colorful peasant smocks and comically unseasonable sheepskin coats, making their uncertain way down the gangplank of their newly-arrived steamer. This was only the beginning —1,300 more recruits would shortly arrive in O’ahu from the deepest, icebound interior of Russia.

If the promise of this burgeoning Siberian colony were fulfilled, the Hawaii Bulletin rhapsodized, “the greatest problem of the islands would be solved.”

The “problem” was Hawaii itself — or rather, the people inhabiting it. The Russians had been told they were coming to Hawaii to work the sugar fields, but they would also provide the valuable, if considerably more passive, contribution of making the islands more white. For decades, Hawaii’s “Big Five” plantations had relied on contract workers from places like Japan, the Philippines and China, who built the sugarcane industry into a juggernaut while swelling the island’s Asian population. The contract system was, however, notoriously exploitative, confining laborers to a life of exhaustion and poverty with little hope of escape. When Hawaii was officially annexed in 1898, the contract system was abolished and the sugarcane workers rebelled, whipping the underlying racism of the white ruling class into a kind of paranoiac madness. Newpaper editorials warned of a dystopian future under Asian rule. Ministers raved about the threat of Buddhist missionaries. In 1905, President Roosevelt himself issued a strongly worded pronouncement that Hawaiian immigration must proceed under “traditional American lines.”

Japanese workers on a plantation in Hawaii, c. 1910. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-ggbain-13386)

Importing Siberian labor was part of a desperate, last-ditch effort to turn the demographic tide in Hawaii, orchestrated by the sugarcane planters, the island elite, and a U.S. congress that feared Hawaii would do the unthinkable and send an Asian senator to Congress. But the weirdest immigration scheme ever proposed by a U.S. territory, also turned out to be the most disastrous. The Russians never provided anticipated relief from Asian workers, because they refused to work at all.

The idea was hatched two years earlier in the far eastern city of Vladivostok, when James Low, a visiting plantation manager, happened to meet a mysterious man by the name of A.W. Perelstrous, a contractor for the Trans-Siberian Railroad. Exactly what Low and Perelstrous discussed is unknown, but at the time Hawaii’s sugar industry was still reeling from a strike at one of O’ahu’s biggest plantations, one that ended with workers winning nearly every concession. Perhaps Low complained about the powerful unions Japanese and Filipino laborers had formed, or maybe he spoke more bluntly about the “yellow peril” menacing the islands. Either way, two years later in July of 1909, Perelstrous mysteriously turned up in Hawaii for a “vacation,” but ended up meeting with Walter Frear, the island’s governor, to suggest his ingenious solution to the island’s labor crisis— recruiting sugarcane workers from Siberia.

Shustov Nikolai Mikhailovich arrived in 1910 with his family - a wife and four children - to work on a plantation. He returned to Russia with his wife and one of their children. (Photo: Russian Collection, Hamilton Library, University of Hawaii at Manoa)

At the time, anti-Asian sentiment was at a fever pitch: 7,000 Japanese sugarcane workers were on strike (among their demands: capping the workday at 10 hours), and plantation owners were hemorrhaging money paying strikebreakers double the usual daily wage.

“There seems to be a general feeling that every available source of white immigration should be tested,” the Hawaii Advertiser wrote of Perelstrous’ proposal. Before the month was over, he had been dispatched to Siberia to launch the recruitment effort.

Three months later, the first group of Siberians reached Honolulu, so jubilant to be free of Russia, according to the local press, that they tore up their passports and scattered them over the Pacific. Despite their “queer” Cyrillic writing, “odd-looking costumes,” and quaint disbelief in eternal summer, the Hawaiians generally delighted with the “comely” girls and “fine-looking” men, who were declared to be the “very kind [the] islands need.”

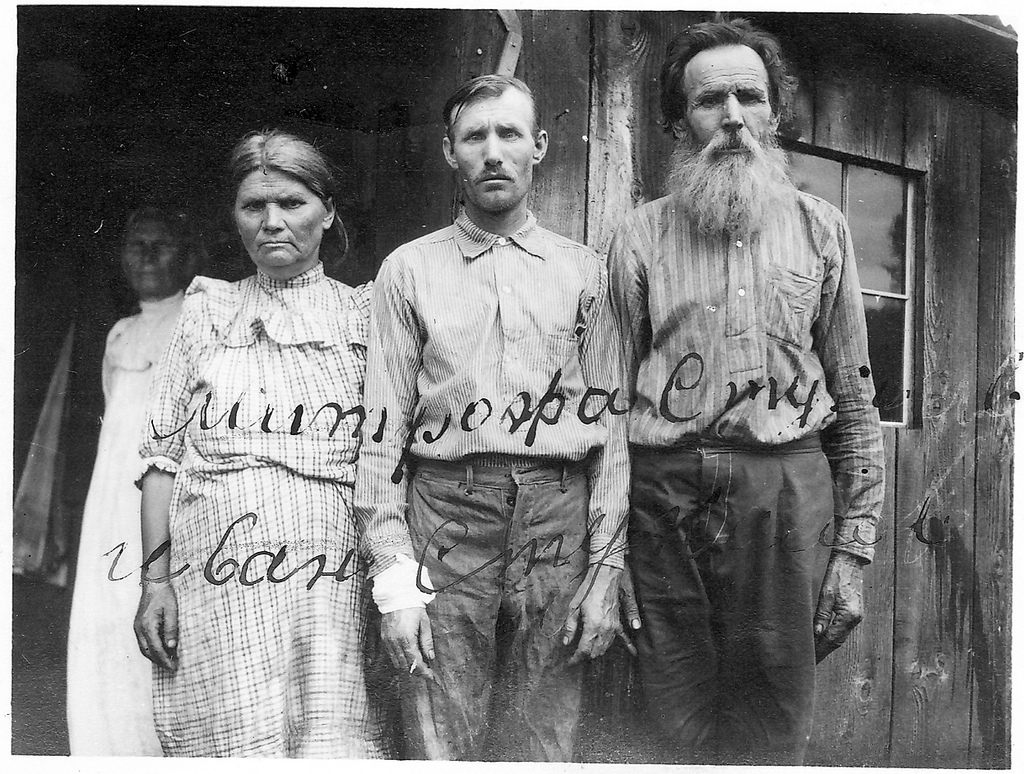

A photo of a Russian family for their passport application for repatriation. (Photo: Russian Collection, Hamilton Library, University of Hawaii at Manoa)

Perelstrous assured the local Immigration Board there was no limit to the number of Russians he could bring to Hawaii. “No promises were needed to bring these hardy peasants, these sons and daughters of the soil,” the Pacific Commercial Advertiser wrote of the businessman’s recruitment campaign. “Women and men fell upon their knees before the agents and made tearful pleas to be allowed to journey to the middle of the Pacific.” What kind of peasant, Hawaiians reasoned, would turn down the chance to swap Siberia’s lunar cold for the tropical beaches of Waikiki?

Yet it turned out Perelstrous (who was doing well enough by then to enroll both of his children at the elite Punahou School, Obama’s alma mater) had made promises to the Siberians, concrete ones, about wages and housing and most importantly, an eventual share in the land they helped farm. They were told that horses were free and food and clothing cost half what it actually did in Hawaii. It was only after the Russians arrived at the plantations to take up the brutal work of sugarcane farming, that they discovered Perelstrous had lied.

The passport application for Chistiakov Petr Markelovich and his family. He had arrived in Hawaii in 1909 on the ship Siberia. (Photo:Russian Collection, Hamilton Library, University of Hawaii at Manoa)

The laborers began circulating a petition stating they’d been “deceived in every word,” and when a second group of Siberians arrived in February of 1910, their malcontent quickly spread. By the time Perelstrous arrived from Russia with yet a third group in March, his countrymen had united against him. A mob of Russians swamped his steamer, angrily brandishing their patched underwear.

“I think there is a big mistake somewhere,” a distraught Perelstrous told reporters. The Immigration Board ordered him to sort out the mess, but when he tried to visit the Russian encampment, he was turned away.

Just like their Asian counterparts, the Russians decided to strike, and what had started out as a hopeful solution to Hawaii’s labor crisis soon turned into a public fiasco sparking protests as far away as Manhattan’s Union Square.

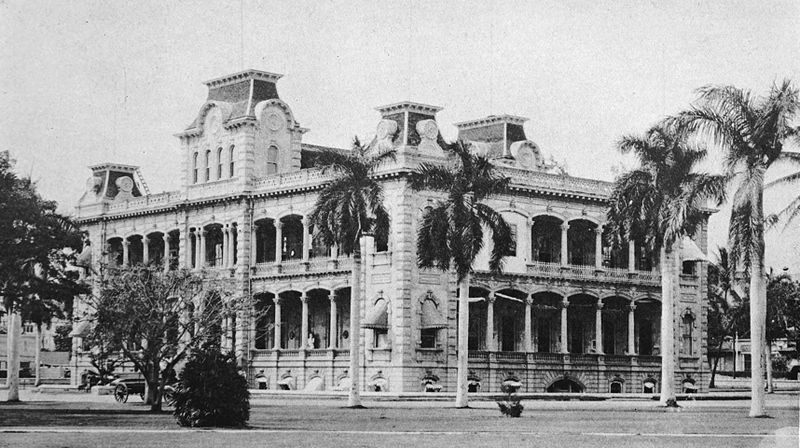

On April 1, 1910, the government made a desperate last attempt to appease the Russians. A meeting was called at ‘Iolani Palace, the former residence of Hawaii’s royal family, where the planters presented the best terms they were willing to offer. The meeting ended in a riot when a group of Russians tried to attack Perelstrous. “We would rather starve and die,” the Russians announced, than work the sugar fields under the planters’ terms,

Their lawyer’s only response was to ask how many coffins he should order.

Iolani Palace, c. 1922. (Photo: Public Domain)

After the failed April meeting, the Siberians were ejected from Quarantine Island, where they’d been housed by the government, and set up camp in the red-light district of Iwilei. Their colorful shantytown, built from tents and packing cases, became a tourist attraction as the Russians were reduced to taking charity and selling their prized samovars for $10 a piece. Lurid tales began to spread about “Russian maidens being sold to the Chinese.”

Six months after their first steamer docked, the dream of a white majority on the island was dead; Hawaii wanted nothing more than to have the Siberians gone. The feeling, it turned out, was mutual. Working piecemeal jobs, hundreds of Russians saved enough money to flee Hawaii for California by the end of 1910. Many returned to Russia. The remaining few eventually assimilated, finding jobs at pineapple canneries, sawmills—even, yes, plantations—and trading their Russian smocks for palaka shirts. The Siberian experiment ended up costing the Hawaiian government $143, 581—about $3.7 million in today’s dollars.

Fominykh Afranasii Ivanovich arrived in 1909 and worked on a plantation for 5 months before leaving for San Francisco. He returned in 1913, and decided against repatriation. (Photo: Russian Collection, Hamilton Library, University of Hawaii at Manoa)

Today there is almost no trace of the Siberians left on the islands, save for a few gravestones and the intriguing scrapbook of a Russian diplomat, who arrived shortly after the Russian Revolution of 1917 to convince 165 remaining families to help build a new communist utopia back home.

As for Perelstrous, his scheme of turning Hawaii into Little Siberia remarkably lingered on for another year and a half with the patronage of Victor S. Clark, Commissioner of Hawaii’s Board of Immigration and a diehard believer in the white settler cause. Their partnership ended when Clark discovered Perelstrous had misappropriated Board funds and smuggled Siberians across the border to China without a passport. In the summer of 1912, Perelstrous and his family said a final aloha to Hawaii, setting sail from the islands and disappearing forever from the pages of history. Clark was forced to issue an embarrassing mea culpa, reassuring Russia that “Hawaii would engage in no further immigration business without official consent.”

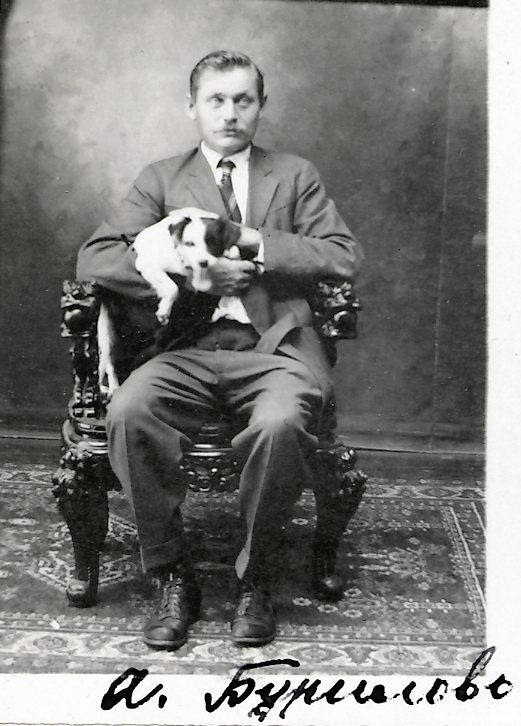

Burilov Andrei Stpanovich arrived in 1910 and worked on plantation. He decided he would not return ”until life in Russia becomes better”. He moved to California instead. (Photo: Russian Collection, Hamilton Library, University of Hawaii at Manoa)

In the ensuing years, Hawaii resumed its course to become the most diverse state in the country, the only one with an Asian majority. When it achieved statehood in 1959, the people elected Daniel Inouye to the U.S. House of Representatives. He went to the Senate a few years later, in 1963, where he served until his death in 2012 as the highest-ranking Asian American politician in U.S. history.

Update, 5/3: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that Hawaii was annexed in 1900. It was 1898.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook