The Teen Who Trekked 1,800 Miles Through the Canadian Wilderness Disguised as a Man

Her ruse worked—until she had a baby.

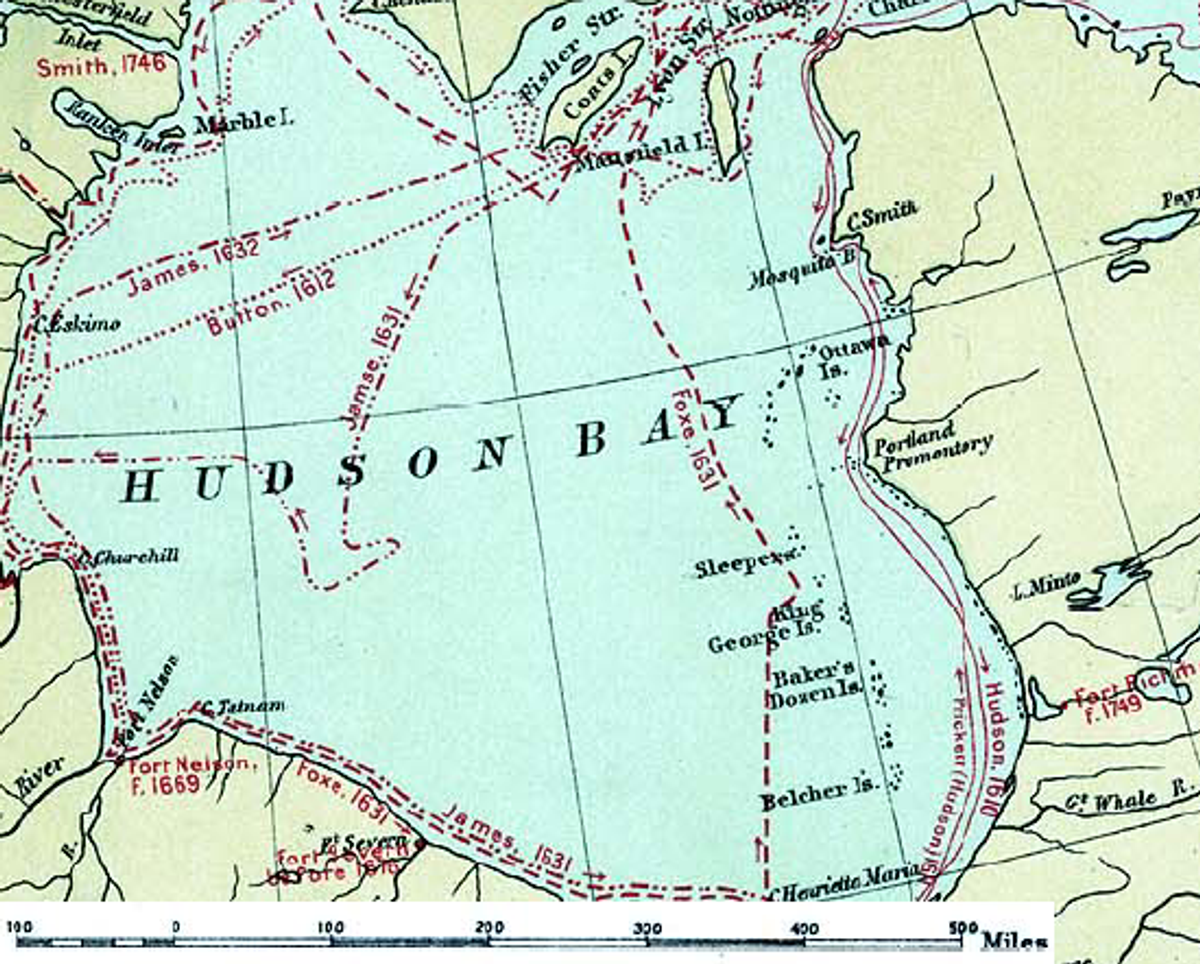

The first European woman to enter western Canada, Scottish teenager Isobel Gunn was only 15 when she disguised herself as a man, traveled to the Canadian wilderness in 1806, and labored for Hudson’s Bay Company for eight pounds a year. Surviving the horrendous working conditions of the early 19th century, Gunn is heralded as a pioneer of feminism.

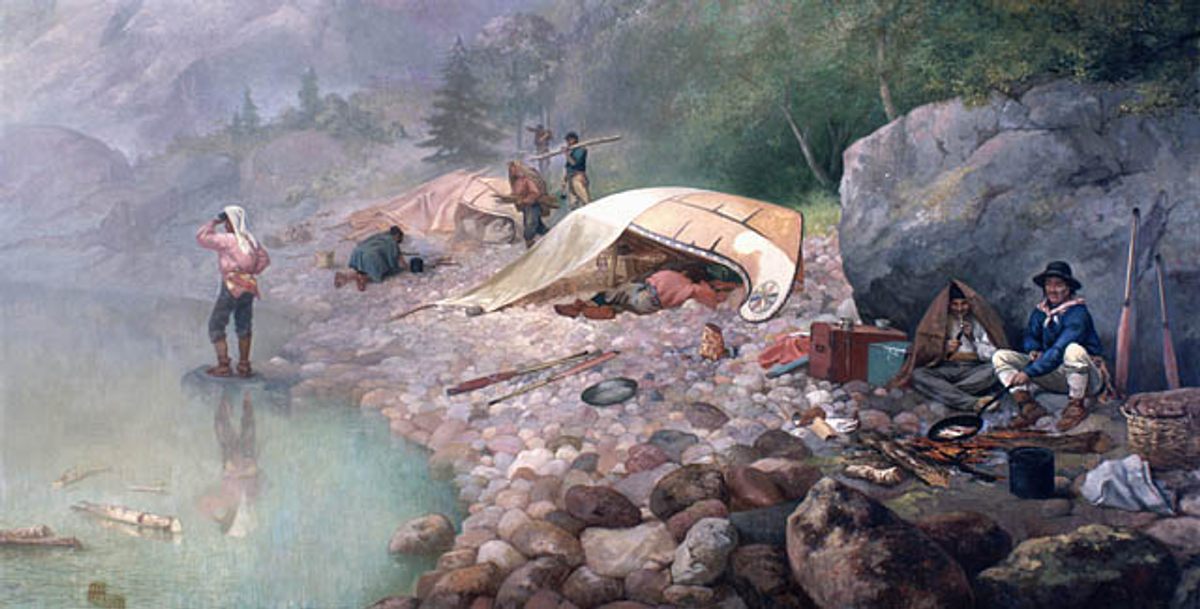

The first employees of Hudson’s Bay were adventurers who undertook back-breaking work in order to support the fur-trapping trade. They had to endure mosquito swarms in summer and freezing winter conditions that saw many perish. Food was often hard to come by and sanitation was non-existent. Working on the Canadian boats–running supplies, collecting furs, and hoisting 90-pound loads on their backs–was dangerous physical work, too hard for most men. So why did a teenage girl from the isolated Orkney Islands defy the all-male rules of Hudson’s Bay and sign up under her father’s name, John Fubbister?

We can’t know Gunn’s reasons for sure, because she didn’t keep a journal and would likely have been illiterate, but some historians believe she was enticed by her brother George, who also worked for the company and would have shared stories of excitement and adventure with his sister.

Others note that early 19th-century Orkney really only gave three options to men: risk life and limb fishing in the dangerous North Sea for a pittance, sign up to fight against Napoleon’s army for a pittance, or join Hudson’s Bay Company, head to Canada, and earn £8 a year—far more than any of the men could earn at home.

As a woman, Isobel would never be able to earn as much as even the poorest male worker in Orkney. And she’d likely need that money—one side of her face was marred by smallpox scars, which would have ruined her marriage prospects. So why not dress as a man and try to earn some money for herself?

Gunn quickly distinguished herself for her bravery. Her canoe treks and expeditions through the most remote stretches of Canada saw her traveling some 1,800 miles between remote trading posts. Hugh Heney, who led one of the brigades Gunn traveled with to Pembina, wrote that she “worked at anything and well like the rest of the men.” She even earned herself a pay rise for performing her duties “willingly and well.”

But on December 29, 1807, she excused herself from work at the Pembina trading post, citing stomach pains to Alexander Henry, who was the head of the post. She begged him to let her rest in his home by the fire. Henry’s journal, reprinted in Stephen Scobie’s The Ballad of Isabel Gunn, notes his reaction:

“I was surprised at the fellow’s demand; however, I told him to sit down and warm himself… I returned to my room, where I had not been long before he sent one of my own people, requesting the favour of speaking with me. Accordingly, I stepped down to him, and was much surprised to find him extended out upon the hearth, uttering most dreadful lamentations; he stretched out his hand towards me and in a pitiful tone of voice begg’d my assistance, and requested I would take pity upon a poor helpless abandoned wretch, who was not of the sex I had every reason to suppose. But was an unfortunate Orkney girl pregnant and actually in childbirth, in saying this she opened her jacket and display’d to my view a pair of beautiful round white breasts.”

Isobel Gunn was having a baby.

Henry’s journal continued: “In about an hour she was safely delivered of a fine boy and that same day she was conveyed home in my cariole, where she soon recovered.”

The name Gunn registered on the birth certificate? Hudson’s Bay laborer John Scarth, who she said had forced himself upon her.

This story is plausible. There are records to show that Scarth had been with Gunn at numerous HBC postings. Some historians say Gunn was trying to cover up an affair gone wrong; others believe she likely was taken advantage of by Scarth, who could have discovered her ruse as a man, and threatened to tell their employer.

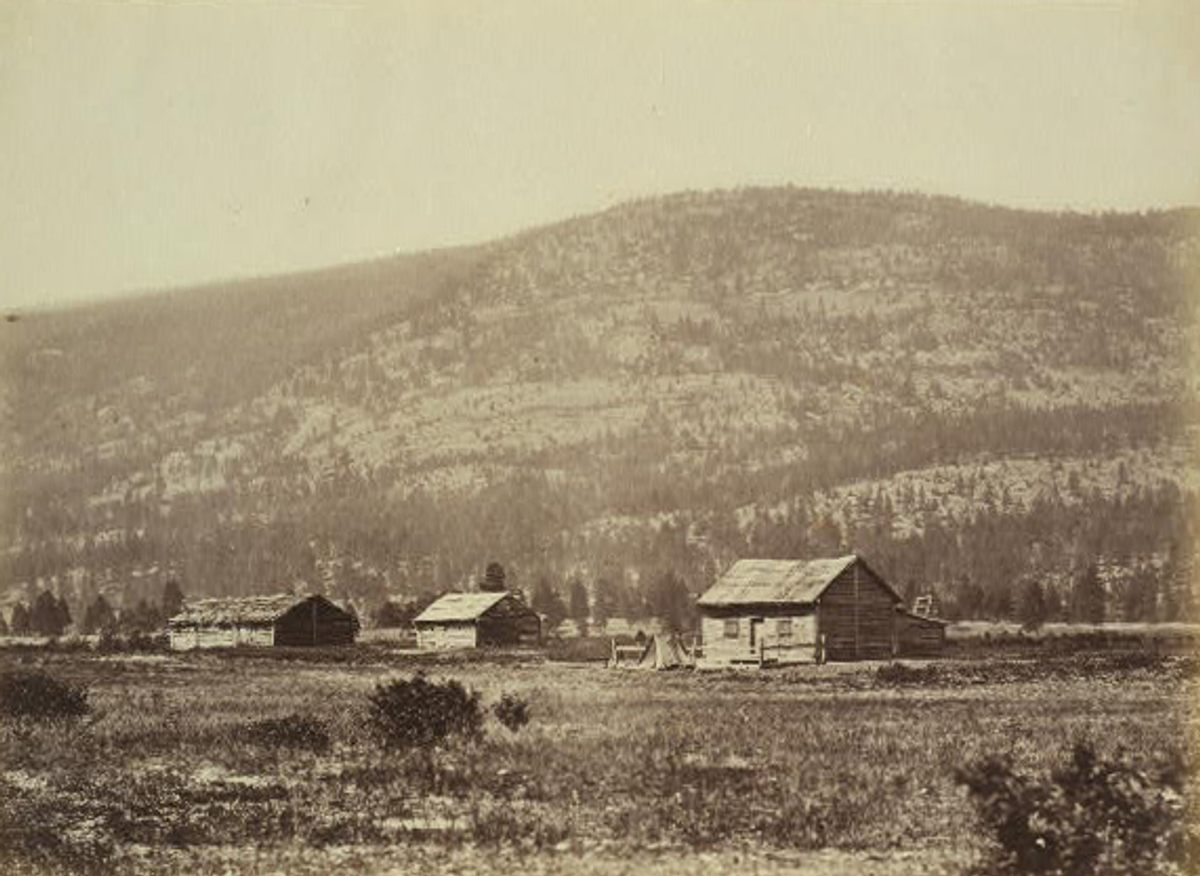

In early 1808, Gunn and her son James were ordered to return to Fort Albany, in Ontario. Upon her arrival, she was no longer allowed to work with the men, but rather was offered work as a washerwoman. Although the boss at Albany seemed sympathetic toward Isobel, Hudson’s top brass didn’t want to be seen to be supporting a woman of “bad character.”

Against her will, Gunn and her child were returned to Scotland after a year. Unmarried and considered “ruined,” Isobel was likely ostracized from her family back in Orkney. She lived in poverty, working as a stocking and mitten maker until her death in 1861, aged 81.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook