It’s Okay to Giggle at the Clown Funeral

Joseph Grimaldi in his Joey the Clown guise. (Image: Public domain/Wikipedia)

On the first Sunday in February, a funeral took place at All Saints Church in Haggerston, North London. At the beginning of the proceedings, clowns entered the church anarchically, causing a ruckus, poking people with puppets, and brandishing balloon animals. This was to be expected, for the occasion was the Grimaldi Service—London’s annual clown funeral.

Every February, dozens of clowns gather to hold a memorial service for Joseph Grimaldi, the father of modern European clowning, who died in 1837. The funeral also honors all clowns who have died in the past year.

The allure of clowns in full “motley” (costume) and “slap” (makeup) at a funeral is strong—the service is open to the public and fills up quickly, even with two levels of seating and some standing-room-only areas. Many people are turned away. Some of those who make it in are dressed as clowns or wearing a red nose, and many have children in tow.

(Photo: Christine Colby)

The service is usually held in Holy Trinity Church in Hackney, which is known as “the Clown’s Church,” and boasts a stained-glass window in honor of Grimaldi. Holy Trinity is under renovation at the moment, which is why this year’s service, the 70th annual celebration of Grimaldi’s life, is at All Saints Church.

On entering the church, attendees are presented with a small Xeroxed guide to the service, complete with lyrics to the hymns and instructions about when to sit and stand. In many ways, this is a standard Christian memorial service, with serious reverence paid to the dead, a Bible reading, and a real priest officiating—Reverend Richenda Wheeler, the vicar of both churches involved.

(Photo: Christine Colby)

But that’s where the similarities end. The first several pews are reserved for the clowns—enough of them to constitute a “giggle,” which is the word for a group of them. Reverend Wheeler is able to get the giggle and the large audience to settle down so she can deliver her introduction. She emphasizes, “we come together today through the desire of many clowns to gather once a year for encouragement and worship. To be able to laugh about the joys and the sorrows of life is something we all appreciate, and our prayer is that clowns everywhere may help us to do this in a Christian spirit.”

(Photo: Christine Colby)

Actor and writer Simon Callow takes the podium, in full motley and slap, and reads “The Life of Grimaldi” by Laurence Senelock. “The clown is all of us, at one time or another,” he intones. Various clowns take the mic after Callow, including Pip the Magic Clown who presents a Bible reading, and Mattie the Clown, who plays along to the hymn “I’ll Be a Sunbeam” on squeaky balloons that appear to approximate a banjo. Gingernutt the Clown helpfully follows along in sign language.

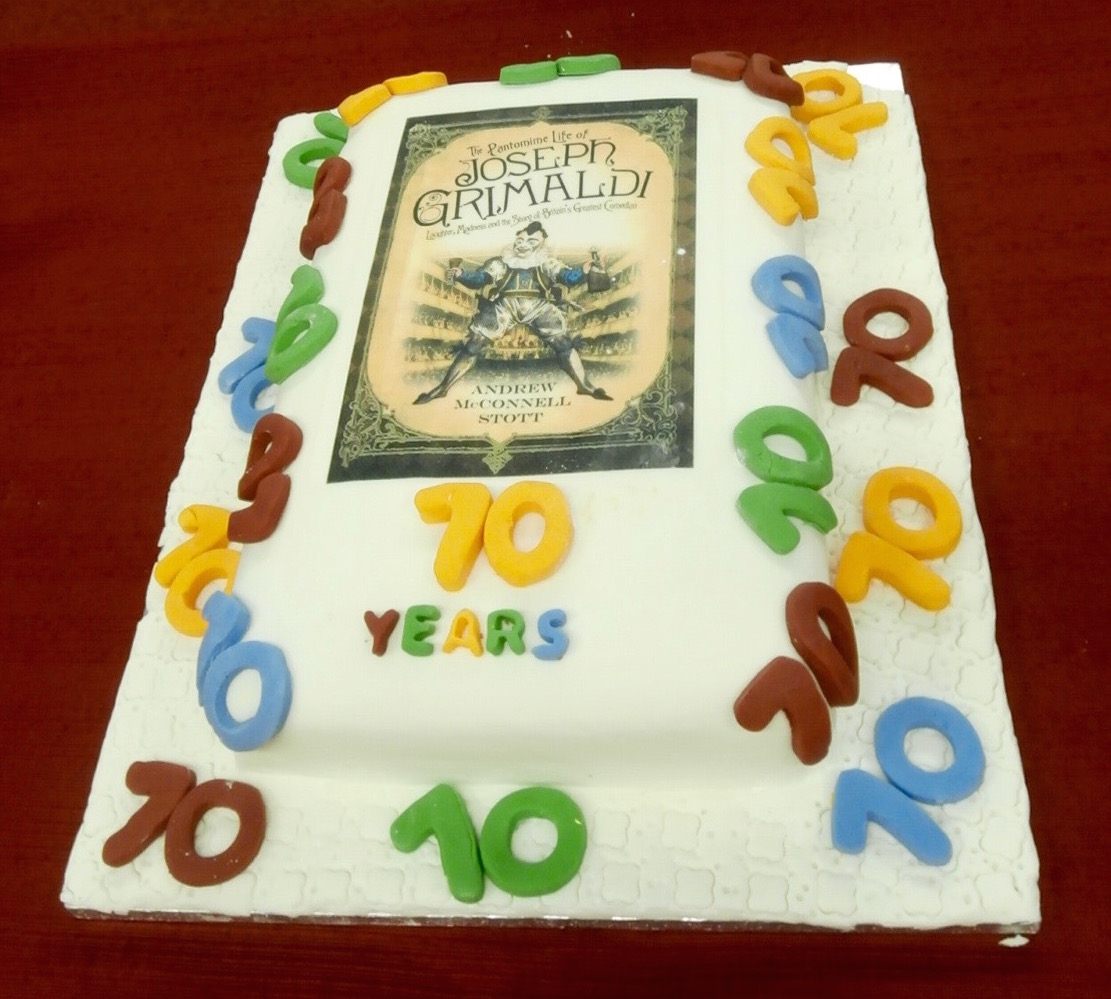

These lighthearted presentations are followed by more serious homilies and hymns, and the congregation stands for a solemn ceremony during which candles are lit to honor clowns who have passed away during the year. Some of this number include Shandy, Joe Fool, Lo-Bo, and Happy. A colorful cake is laid on the altar in honor of Joseph Grimaldi, and the clowns join together to recite the Clown’s Prayer: “Dear Lord, I thank you for calling me to share with others your most precious gift of laughter. May I never forget that it is your gift, and my privilege. As your children are rebuked in their self-importance and cheered in their sadness, help me to remember that your foolishness is wiser than our wisdom.”

A cake to honor Grimaldi. (Photo: Christine Colby)

As the packed pews empty out, clowns and children run riot in the church courtyard. One clown is playing a harp adorned with some sort of animal skull. Another has climbed a lamppost and is using his extra large shoes to stomp on the heads of bystanders. A police clown is directing traffic. Madness erupts as everyone wants photos with the clowns and they all act up for the crowd, attempting to draw attention, in spite of the cold temperature and biting wind.

(Photo: Christine Colby)

While the main event is over, there is still more to see. The Clowns Gallery Museum and Archive, usually only open on the first Friday of each month, opens its doors half an hour after the end of the service. It’s a 10-minute walk away, a tiny space jam-packed with clown collectibles hidden around the back of Holy Trinity church. A banana peel lies on the sidewalk. Left there deliberately? Hard to tell.

A car pulls up and clowns spill out—a real-life clown car! While one of them unlocks the door and goes around turning on the lights, another, a kindly gentleman clown named Jolly Jack, comments on the cold and asks if anyone would like some tea. He putters in a small cabinet, turning on the electric kettle and readying some mugs, while beginning to explain some of the treasures in the museum.

Inside the clown museum. (Photo: Christine Colby)

One of the most compelling exhibits is the large collection of eggs painted with clown faces. Jolly Jack explains that a performer’s costume and makeup style is proprietary, and no other clown can use the same design—although it can be handed down within families. In the 1940s, Stan Bult of the International Circus Clowns Club began the Clown Egg Register as a way to trademark each performer’s makeup design. Bult used hen eggs, so not all have survived due to their fragility. Clowns are still registering their signature slap on eggs, but these days, pottery eggs are used.

Made-up faces from the Clown Egg Register. (Photo: Christine Colby)

On one wall is an oversized, button-covered red jacket formerly owned by Britain’s celebrated Coco the Clown. Coco’s son, who also used the name Coco, was hired by McDonald’s in the mid ’60s to redesign the Ronald McDonald character. Coco’s yellow-and-red design is still in use today.

While small, the museum is so full of fascinating artifacts that it’s definitely worth a visit. And having tea with a jokester named Jolly Jack while looking at shelves of painted eggs is the perfect coda to a clown funeral.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook