At a Festival in Bhutan, Some Dancers Bare All to Ward Off Evil Spirits

One of the many traditional dances at the annual Jambay Lhakhang Drup involves performers in masks—and nothing else.

Excerpted and adapted with permission from High: A Journey Across the Himalaya, Through Pakistan, India, Bhutan, Nepal, and China, by Erika Fatland. Published January 2023 by Pegasus Books. All rights reserved.

The gateway to Bhutan lies halfway between the Indian town of Jaigaon and the Bhutanese town of Phuntsholing (293 meters/961 feet above sea level), only the two border towns have grown together so one scarcely notices that one has moved from the world’s second most populous country to a Buddhist kingdom with fewer than one million inhabitants. In addition, most of the roads in the two towns are one way, so one has to take a considerable detour to get there, which often entails crossing the invisible border between the towns several times en route, which only amplifies the labyrinthine feeling.

With the exception of Indians, Bangladeshis and, for some reason, Maldivians, all foreign tourists who visit Bhutan must pay a fixed amount per day, equivalent to around $250, for an all-inclusive package that covers the guide, car, driver, accommodation, and food. The driver and guide met me at the hotel on the Indian side in order to help me navigate my way through the border formalities. They were both wearing traditional Bhutanese clothes, obligatory for anyone working in the public sector and tourist industry.

Sonam, the driver, and Sangye, an energetic, brash man who would be my guide, wore the gho, which is a kind of woven, knee-length dress that is held together by a thick, tight belt, so that the material creates a voluminous pouch over the stomach which can be used to hold everything from babies to wallets. Knee socks are part of the outfit, but for the sake of comfort, anything goes when it comes to footwear, including trainers. Women wear the kira; the modern variant consists of a woven, wraparound skirt that is held up by a belt, but in the past the kira was normally draped over the shoulders and fastened with a brooch, like a dress. The costume includes a long-sleeved blouse and short silk jacket, often in different, but matching colors.

The first time I visited Bhutan, I was utterly taken with these exotic outfits and really felt that I had come somewhere different, a special and unique place. But they no longer had the same impact on me; they were already everyday garments. The first impressions of a place and people are priceless, you are open and receptive, and soak up all the unfamiliar details. But the second impression allows you to go deeper, to see beyond the surface.

I am not sure when we actually crossed the border itself, but when the shop signs started to be written in Tibetan, I realized we were in Bhutan. No one knows exactly where the name Bhutan comes from, though it may be an adaptation of the Sanskrit word Bhota-anta: “end of Tibet.” The Bhutanese themselves call their country Druk Yul, or Land of the Thunder Dragon.

In the next street, all the signs were written in the Indian Devanagari alphabet, so we were presumably back in India, only to return to the Thunder Dragon’s land minutes later. After we had driven up and down and back and forth, following all the one-way streets for some time, we arrived at the tiny immigration office by the Bhutan Gate. The man at the computer was also dressed in a gho. He took my passport and with a smile adorned an empty page with a triangular stamp and welcomed me to Bhutan.

Thimphu, the capital, lay some 2,000 meters (6,561 feet) higher than Phuntsholing. The road twisted and turned steadily upwards, with green, subtropical vegetation and forest on either side. Bhutan is something of a rarity in that it absorbs more CO2 than it emits; one of the reasons for this is that the government has decided that at least 60 percent of the land mass should be forested. More than 70 percent of the small kingdom is now covered in trees. Monkeys sat by the side of the road picking each other’s fleas as they waited for cars in the hope that they might be thrown a tidbit.

In terms of capitals, Thimphu is not big, with about 115,000 inhabitants, or about 15 percent of the total population. As the capital sprawls over a large area, it actually feels bigger than it is. All the buildings are in the traditional style, with painted wooden details and low sloping roofs, which gives the city a more attractive and holistic feel than Indian cities, where concrete dominates. A policeman stood on a beautifully decorated column in the middle of the city’s only major intersection, directing the traffic with soft, fluid movements. Thimphu is quite probably the only capital in the world without traffic lights.

From Thimphu, the journey to Bumthang was long, through rhododendron forests and over steep mountain passes where thousands of colorful prayer flags hung next to one another. We also drove past litters with fluttering white flags—prayers for the dead. Often only worn tatters remained.

It was dark by the time we arrived in Bumthang (2,800 meters/9,186 feet elevation), which lies more or less in the middle of Bhutan. Bumthang normally has a population of about 5,000 people, but that number had tripled for the festival known as Jambay Lhakhang Drup. There were cars and people everywhere, but, unlike in India, there was no hooting. The drivers waited patiently for the traffic jam to unknot itself.

The small square in front of the temple was thronged with people. Muscular monks in saffron silk skirts and grotesque wooden masks danced slowly in a ring round a fire. Four poles stood crossed over the fire, holding up a picture of a goddess. A lone monk sat inside the temple slowly banging his cymbals: Cling! … Cling! … Cling!

“It’s very good for women to see this ritual,” Sangye whispered. “Especially women who can’t have children,” he added, nonchalantly. As though they had been given some secret signal, most of the audience suddenly ran towards the open ground behind the temple. There was a door-like structure in the middle: two upright poles with a long pole laid across. It was decorated with spruce branches. A handful of monks approached with burning torches and set the spruce alight. Seconds later, the whole installation was in flames, and people started to run through the burning portal. Round and round they ran, again and again, several thousand people shouting and cheering, with their jackets over their heads so their hair would not catch fire, old women, young men, children—everyone was running. The minutes ticked by, the flames grew higher and higher, and burning spruce branches fell to the ground, but no one stopped running until the fire was almost out.

“This ritual is very good for women,” Sangye said thoughtfully. “Especially women who can’t have children.”

The high point of the evening would take place later, but no one knew exactly when. “The dancers will come out when they’re ready,” Sangye said. “They have to drink for courage first.” In the meantime, more people arrived in cars and taxis from outlying valleys. Songs and commotion could be heard inside the temple.

“The dance that will be performed soon was created by the great tantric master, Dorje Lingpa, in the 14th century,” Sangye said. “He came here to help the locals build a temple, but a swarm of evil spirits played havoc with the work. The master created the dance to distract the spirits, and while they were held mesmerized, the temple was completed. The dance has been performed here in Bumthang every year since, and it is very holy. When the dancers show their treasure, they frighten off evil spirits and bless the audience. All sentient beings come into this world thanks to the treasure.”

Sixteen visibly intoxicated men came staggering out of the temple. They had wound long strips of cotton cloth around their heads, so only their eyes were visible. But other than that, they were stark naked. The tantric temple dances are normally performed by young monks, but this particular dance is performed by selected men from the surrounding valleys.

The night was cold and clear. This had an obvious effect on the “jewels,” which shrank and almost disappeared. The dancers gathered around the fire, then stood there tugging and pulling at their penises while jumping up and down to keep warm. Every so often they would loosen up and make indecent, sexual moves against each other. The audience whooped and laughed; they wanted more. The keenest had got there hours before to guarantee a place at the front, and watched the spectacle in reverential silence. Sangye and I had not been fast enough, and had to be thankful for a place much further back. We did not have a great view of the treasure until the 16 naked men suddenly paraded right past us on their way to one of the other temples. Several of the dancers held their hands protectively over their treasure as they snaked through the crowd.

“Move your hands! Show us your jewels!” people shouted with indignation. Some even hunkered down to get the best possible view. “It is important to watch the dance with your family,” Sangye said. “During the dance, you have to concentrate and focus on the treasure. It will absolve your sins and bless you. It is particularly beneficial for women who can’t have children,” he said, meaningfully.

When the dancers returned from their round of the other temples, they huddled side by side by the fire to get warm again. Someone in the audience shouted something and moments later the naked men launched themselves furiously at the crowd and started to thrash a young man. People shouted, roared, and pushed.

“It’s best we go now.” Sangye took me by the arm and led me away from the crowd. “I think someone tried to take photographs.” It turned out that someone had indeed pulled out their phone, but only to check the time. Not that it mattered—the holy dance was definitely over for the night.

The daytime rituals were not as popular. With the exception of some interested older people who had settled themselves on blankets and cushions at the front, with picnic baskets and thermos flasks, the audience consisted of tourists and guides. Like the evening before, one monk played the cymbals while four men in wide, yellow skirts rotated slowly around the square, with theatrical, ritualistic movements. In front of their faces they held heavy, red wooden masks with sharp teeth and bulging eyes.

“This dance was also introduced by Padmasambhava in the eighth century,” Sangye said. “The monks have to conquer the evil spirits and capture them in the triangular box that’s there on the ground.”

Quarter of an hour later, when the evil spirits had been caught and conquered, the dancers disappeared into the temple and a new group came out into the square, also wearing wooden masks and wide, yellow skirts. As the dances progressed, the masks became ever more terrifying, culminating in the death dance, where the monks danced with long swords that they dragged along the ground. The black wooden masks had white skulls painted on them. A kind of clown, in a bright red mask and black clothes, raced and leaped around with a huge, red, wooden phallus in his hands. He hit people on the head with it and made vulgar movements in front of the audience, who laughed and threw him money.

“If he touches you with his organ, it will bring you good luck,” Sangye said. “Especially women who can’t have children.” He gave me a meaningful nod.

“Where is everyone?” I asked. “The square was packed yesterday, and now there’s only tourists.”

“Most people don’t spend their time up here,” he grinned. “As locals, we have to wear our formal, traditional clothes to get into the temple area. Right now, most of them are probably still asleep.”

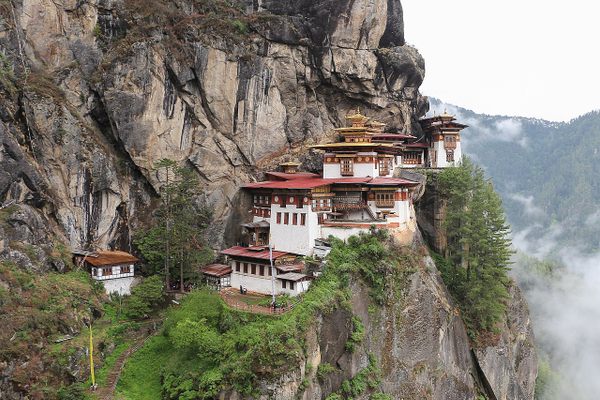

Sangye took me over to the temple that the drunk, naked men had danced around the evening before. The building had been lime-washed, with a red stripe painted just below the yellow roof. The roof itself had an even smaller structure on top, which looked a bit like a treasure chest. “This is one of the oldest temples in Bhutan,” Sangye said. “In the seventh century, a terrible demon wreaked havoc throughout Tibet and Bhutan. In order to calm her, King Songtsen Gampo, the Tibetan regent, had 108 temples built in one day. This is one of those temples.”

As the sun was setting, and a purplish-blue light settled over the valley, Sangye decided it was time to show me where the rest of the people were. We left the temple compound and went down to the open space behind the car park, where carousels had been set up for the children alongside a number of food tents and stalls that sold everything from water pistols to cheap Indian clothes. Beyond these, I could see people crushed in between the gambling stands. They all offered the same games, with minor variations: you put a 100 ngultrum note or two on a symbol or number, then the dartboard was spun round so quickly that it was impossible to differentiate the symbols from the numbers. One of the players would throw a dart, and if you were lucky he would hit your number. Bands of cheering men had gathered by the booths. Sangye was the only one wearing traditional dress; all the others were in jeans or tracksuit bottoms.

“Strictly speaking, gambling is banned in Bhutan. It’s only permitted at festivals such as this,” Sangye explained, and put 100 ngultrum note on his lucky number. He lost every single bet. And so did I. “I should have won today,” he said. “It’s my birthday. I’m 34. But we don’t celebrate birthdays in Bhutan anyway, so it doesn’t really matter.” Soon we had almost run out of cash, but had enough to buy a Bhutanese whisky each. It tasted strong and sweet in the evening chill.

We walked back up to the square in plenty of time for the evening’s display of the treasure, and were rewarded with excellent places at the front. We could already hear loud singing, nervous laughter, and talking from inside the temple. Tourists, grandparents, teenagers, and children gathered. After about an hour, the naked dancers had the courage to come out of the temple. They seemed to have warmed up more this evening, and it did not take long before they were leaping round the square, energetically swinging their treasures up and down, quite literally in front of everyone’s noses. One of the dancers had brought a flashlight and he shone the beam over his comrades’ jewels so nothing was left to the imagination.

“You should fold your hands and pray for something,” Sangye said. “Women without children normally pray to get pregnant,” he added helpfully.

The sky was dark and clear, and the waxing moon shone over the temple and the 16 dancing men. When the last of them had returned to the temple, we followed the hordes out to the car park, where we found the car but not the driver. Sangye rang him, and not long after Sonam came running up from the marketplace.

“Did you win or lose?” I asked, but I could already tell from his face what the answer was. Fairgrounds in every country are suspiciously alike.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook