Joining the Caterpillar Club Is as Easy as Escaping a Fiery Plane

A golden bug worn on the lapel could indicate a life of adventure.

One of the pins issued to members of the Caterpillar Club. (Photos: Jacek Halicki/CC BY-SA 3.0)

If you ever see someone sporting a golden caterpillar on their lapel, you’ll know they’re a member of a prestigious—and quite baffling—club. But the wearer of the gleaming bug brooch didn’t pay any dues to join this obscure club: membership is involuntary.

The sole requirement for joining the Caterpillar Club is to make an emergency escape from a failing aircraft, then plummet to earth with the aid of a parachute. Should you survive, you automatically become a member.

The Caterpillar Club, which has no officers, no local chapters, and no formal organization, has been around since 1922. On October 20th of that year, Harold Harris, an army test pilot, engaged in combat practice in a monoplane over Dayton, Ohio. Harris lost control of the aircraft, slid out the top of the fuselage, and deployed his never-before-used parachute. He landed shaken but very much alive.

Prior to the incident, reported the Oakland Tribune in 1928, “there was more or less skepticism among air men as to the ability of the flier to think and act rapidly enough to get free of a falling plane and operate a parachute before too great a loss of altitude for safety.”

Harris’ survival was proof that parachutes could indeed save lives.

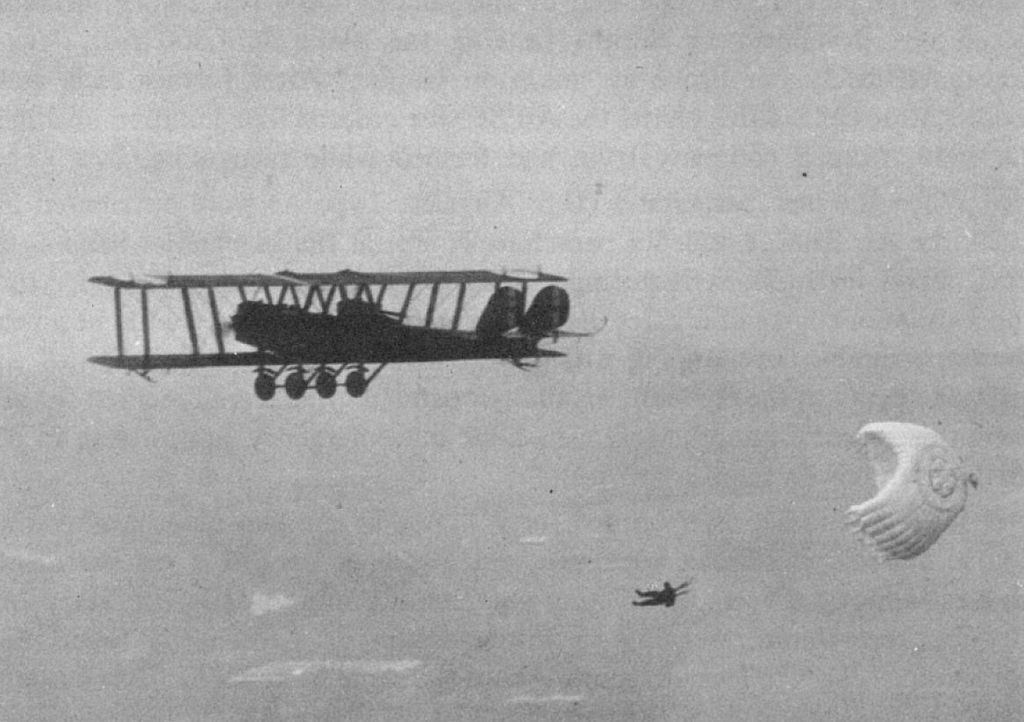

A parachute being tested at McCook Field, Ohio in 1922. (Photo: Public Domain)

In the weeks following Harris’ daring escape, Dayton Herald newspapermen Maurice Hutton and Verne Timmerman and government parachute engineer M. H. St. Clair became inspired to start the Caterpillar Club, so named because parachutes were made of silk. As St. Clair told Flying Magazine in 1932: “The lowly silk worm or caterpillar spins a cocoon, crawls out and then flies away from certain death.”

Parachute manufacturers soon got wise to the promotional opportunities offered by the Caterpillar Club, which Flying Magazine called “a somewhat mythical group” that “[n]o one seeks to join.”

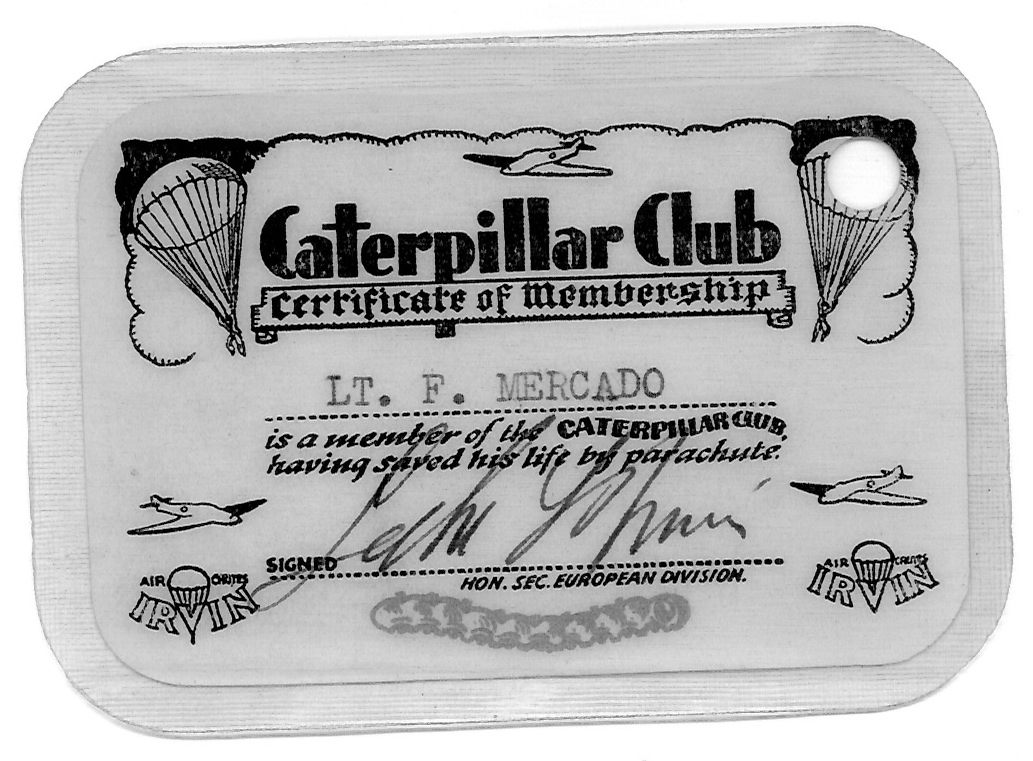

The Irvin Air Chute Co., which had been in the parachute-making business since 1919, issued membership cards and golden caterpillar pins with amethyst eyes to anyone whose life had been saved by one of their products. (Some versions of the Caterpillar Club origin story hold that founder Leslie Irvin was part of the 1922 discussion that invented it.) The Switlik Parachute Company also sent black-and-silver caterpillar pins to those who had deployed its chutes in an emergency.

A membership card from Irvin Air Chute Company. (Photo: Dmercado/CC BY-SA 3.0)

By 1928, the Oakland Tribune reported that there were 87 living members of the Caterpillar Club in the United States. These included Charles Lindbergh, who, thanks to a wild couple of years in the mid-20s, was “a member of the Caterpillar Club by virtue of no less than four emergency leaps, two of them at night, while flying the air mail.”

Female flyers were caterpillars, too—in 1925, Irene McFarland became, in the words of the Modesto News-Herald, “the first woman to invade the club” after an aerial circus stunt went wrong in Cincinnati, Ohio. The publication also noted that the designers of the caterpillar pins “may have chosen a masculine design because no one thought that feminine adventurers would wear them.”

World War II saw an exponential increase in Caterpillar club members. A 1977 count conducted by Irvin Aerospace—the successor to the Irvin Air Chute Co.—found that 11,332 men and 12 women had been sent a gold pin and membership card after their emergency use of an Irvin chute had been verified.

The Caterpillar Club may be less relevant now—the initial enthusiasm for it, at least among the parachute manufacturers who issued pins, was to promote their products, which were little-trusted. With parachutes now standard, and made of nylon rather than silk, caterpillar pins have become scarce.

That said, if you’ve ever bailed from a failing aircraft, parachuted to safety using an Irvin product, and want something to show for it beyond the glory of being alive, get in touch with Airborne Systems, which owns the parachute producers Irvin Aerospace, GQ Parachutes, Para-Flite and AML (Aircraft Materials, Ltd).

In accordance with the Irvin protocols established in the 1920s, the company still issues gold pins and membership cards to Caterpillar Club members.

Object of Intrigue is a weekly column in which we investigate the story behind a curious item. Is there an object you want to see covered? Email ella@atlasobscura.com

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook