Ken Burns on His Obsession With Ben Franklin, and Admiration for Guy Fieri

The documentary filmmaker talks about a founder’s flaws, radical openness, and road tripping for a sandwich.

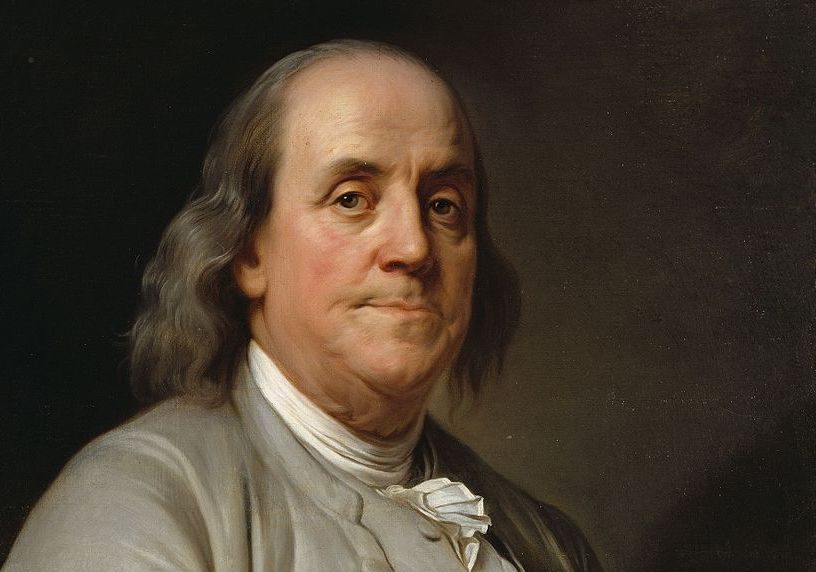

It seems absurd to ask, but who was Benjamin Franklin, really? The American founder’s legacy is at once ubiquitous and somehow elusive. He was never president, nor a cabinet secretary—he’s not even name-checked in Hamilton. Surveying his various careers as a scientist, inventor, writer, publisher, and diplomat, one could be forgiven for not properly engaging with any of them. Call it the curse of the polymath.

That was the challenge before filmmaker Ken Burns, whose new, two-part documentary, Benjamin Franklin, premiered April 4, 2022 on PBS. The famed documentarian spoke with Atlas Obscura about Franklin’s enduring relevance, misunderstood politics, endless curiosity, and manifest flaws—including, of course, a lifetime of slave-ownership before a late-in-life awakening.

Burns—whose films cover everything from baseball to country music—also shared some insight into his own secret obsessions.

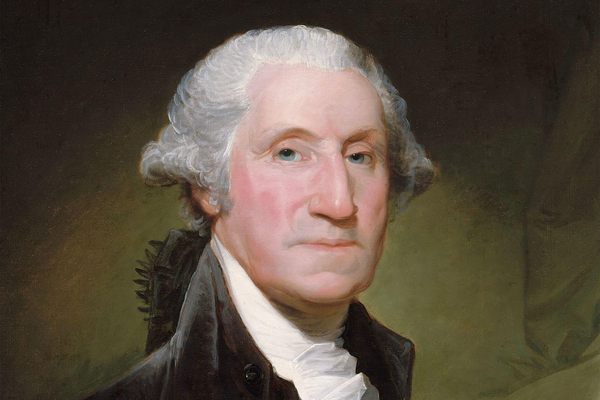

You made a film about Thomas Jefferson. HBO did a series about John Adams. Then there’s Hamilton. So, why Benjamin Franklin and why now?

Well, there’s no “now.” This is a project that was begun five years ago. We had zero idea what the “now” would be like. I’ve just been drawn inexorably to Franklin, to arguably the most important person in that whole founding period. And more importantly, I think because he’s accessible and knowable, he provides us a kind of portal into that founding, warts and all. We can appreciate his own journey, the shedding of many of his own flaws and understanding what those flaws were.

After watching the film, it definitely feels like he would have been the most interesting commentator on today’s world, out of all the Founding Fathers.

Yeah, I think so…. He was social media. He was a printer. He was a publisher. He produced books, almanacs. He was the postmaster. He was Apple and Google and Twitter and Facebook all in one. He’d understand it completely. He spoke in aphorisms and tweets. Of course he’d get it. And he’d be disappointed at our partisanship because he was all about compromise.

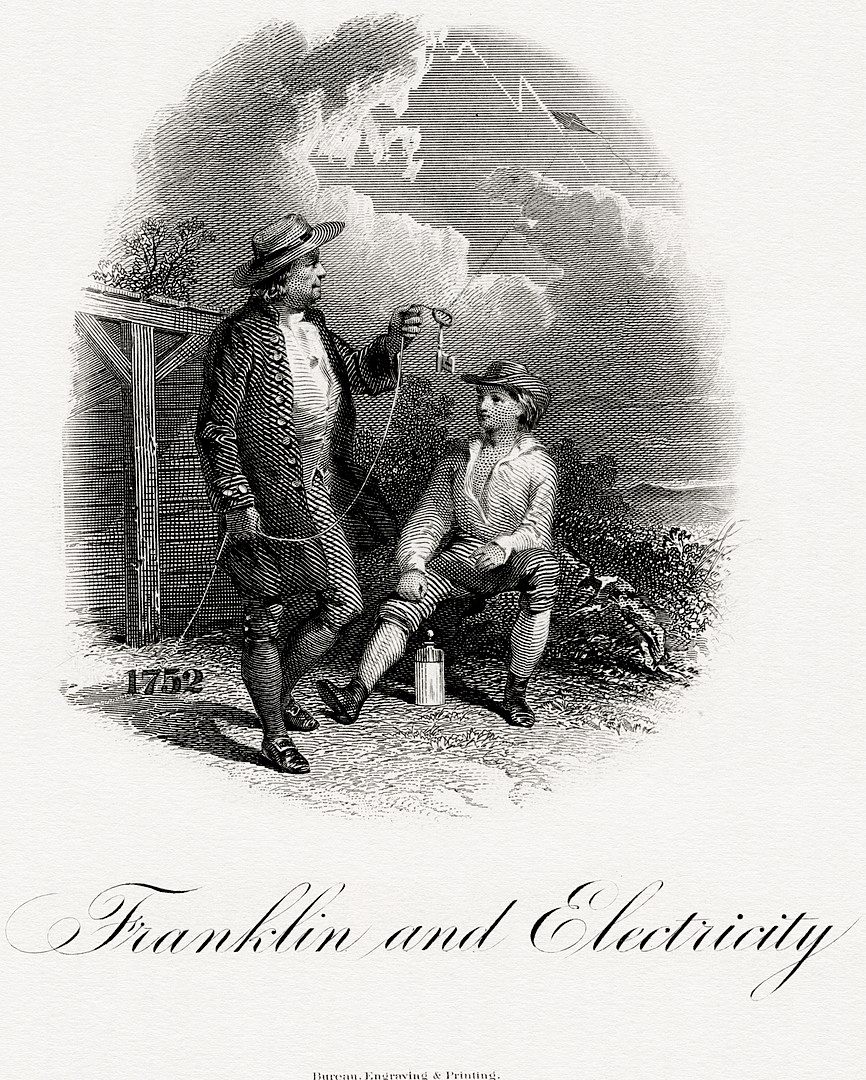

Hypothetically, how might he have participated in the conversation around vaccination, considering his experience with his son Frankie?

Yeah, but that’s misunderstood. He was a huge proponent of vaccinations, we should say inoculations, that’s the more accurate term. So he is a huge proponent in his writing, and he was planning to get Frankie inoculated, but Frankie was sick. And so because inoculations were so hard on the system, it was very difficult to figure out how to do it. And [Frankie] had a bad cold. So they waited until the cold was over, and by that time Frankie had smallpox and died. And then it fell to [Benjamin], this big social media titan, to have to explain to the public why inoculations were good and how tragic it was and sort of bare his soul, to have to live out a tragedy in a life that was examined all up and down the United States.

Do you have a favorite piece of Franklin writing that you discovered in the course of making this film?

You know, I did. And it’s spiritual. He said: “Here is my Creed. I believe in one God, the Creator of the Universe. That He governs it by his Providence. That he ought to be worshiped. That the most acceptable service we render to him is in doing good to his other children. That the soul of man is immortal, and will be treated with justice in another life respecting its conduct in this. These I take to be the fundamental points in all sound religion, and I regard them as you do in whatever sect I meet with them.”

Here we have a guy who’s on the $100 bill. It’s the largest bill in general circulation in the United States. Everybody wants more Benjamins, right? And so he’s been held up for generation after generation—almost while he was still alive—as the example, the American example of pulling yourself up by your bootstraps, doing it on your own, self-reliance, all of this sort of stuff, and is held up as a kind of god by libertarians. They’ve only got half a $100 bill, and I don’t mean $50. They don’t have Grant. This thing has been torn in half because this other half is not just that striving. It’s the civic engagement and the civic responsibility. It’s what he says in that creed: You’ll be judged by what you’ve done for others. And so all of his magnificent inventions are held without patents, which could have exponentially exploded his wealth. But he wanted to give something back.

And this is not to ignore the owning of other human beings. This is not to ignore the kind of romanticization of native populations [while] participating in a massive dispossession of land. It’s not that you can sort of give lip service to the education of young women but don’t see fit to do it for his own daughter, [or] leave your wife for 15 out of the last 17 years of her life, though you know she’s ill and had a bad stroke but you haven’t made the trip back. So it’s, to me, endlessly interesting and so contemporary. And it makes that period accessible because he has all of these flaws that seem human.

Atlas Obscura is planning a series on “Secret Obsessions.” Ben Franklin was so eclectic and poured himself into so many different pursuits throughout the course of his life, as you have. So, what’s your secret obsession?

I’m obsessed with Diners, Drive-Ins and Dives. I hate anything on the cooking channels that’s a competition. It’s all about, to me, making good food and having this weird guy celebrate every possible type of cuisine in the United States, every possible ethnicity, every possible race. It’s just, to me, exciting. When my daughter, Olivia, was home from school a couple of months ago, we got in the car and drove two and a half hours—the most you can go east and west in our tiny state of New Hampshire—to pick up lunch at a particular place that we had seen. And none of us have the bandwidth to ever do that kind of spontaneous, “Let’s do it,” but we woke up on a Sunday morning and I looked at her and I said, “Let’s do it.” We did this spectacular drive, and it was like thieves. We were back six, five and a half hours later, having had this wonderful meal and happy that we did it.

What did you get?

I got a fish, sort of a crab cake fish sandwich from a place in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and Olivia got some elaborate Korean thing. And it was this restaurant that was basically about all the street food that you could get from all these different nationalities. It was very cool and lived up to all of the hype that we saw Guy Fieri do with it. And, in fact, one of the things that they made on the show is the thing I got: this fish sandwich. Fieri is like nails on the blackboard to [a lot of people], and just a hustler. And I disagree completely. I just think he’s ecumenical and open to stuff that people make. And there are very few people [like that].

To bring it back to Franklin, is there a secret or obscure invention, achievement, or interest of his that you find just as compelling as the more notable ones?

I think it’s the armonica [or bowl organ]. It’s such a beautiful thing. As somebody said, it was “celestial ravishment.” Talk about obsession … it’s a classic Franklin thing. So his obsession is this unstoppable curiosity, right? I mean, he cannot stop looking at the world and looking inward and looking at the affairs of human beings. And, because of his wisdom, seeing it in a way that helps us make it modern, translatable. We lose the awkwardness of the breech pants and the waistcoats and the powdered wigs. We’re into just stuff that sounds like today with him.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook