Where Are the Last of Maine’s Historic King Pines?

Deep in the wilderness, some say, forest giants claimed by the British Crown still tower above lesser trees.

On a bright, buggy June day, I set off across a Maine river into a preserve called The Hermitage. I was in search of a pine tree claimed by the king of England centuries ago. Snow, mud, and raging water make the preserve impassable at different times of the year, but in early summer the river reached just above my ankle. Ahead of me, on the river’s north bank, sloped a stand of tangled beech, sugar maple, and hemlock—and then, rising above the understory, the straight mud-brown trunks of eastern white pines, crowned by ragged branches at their peaks. These were big trees, ancient trees, more than 120 feet tall, the kind you don’t expect to see on the logging-decimated East Coast.

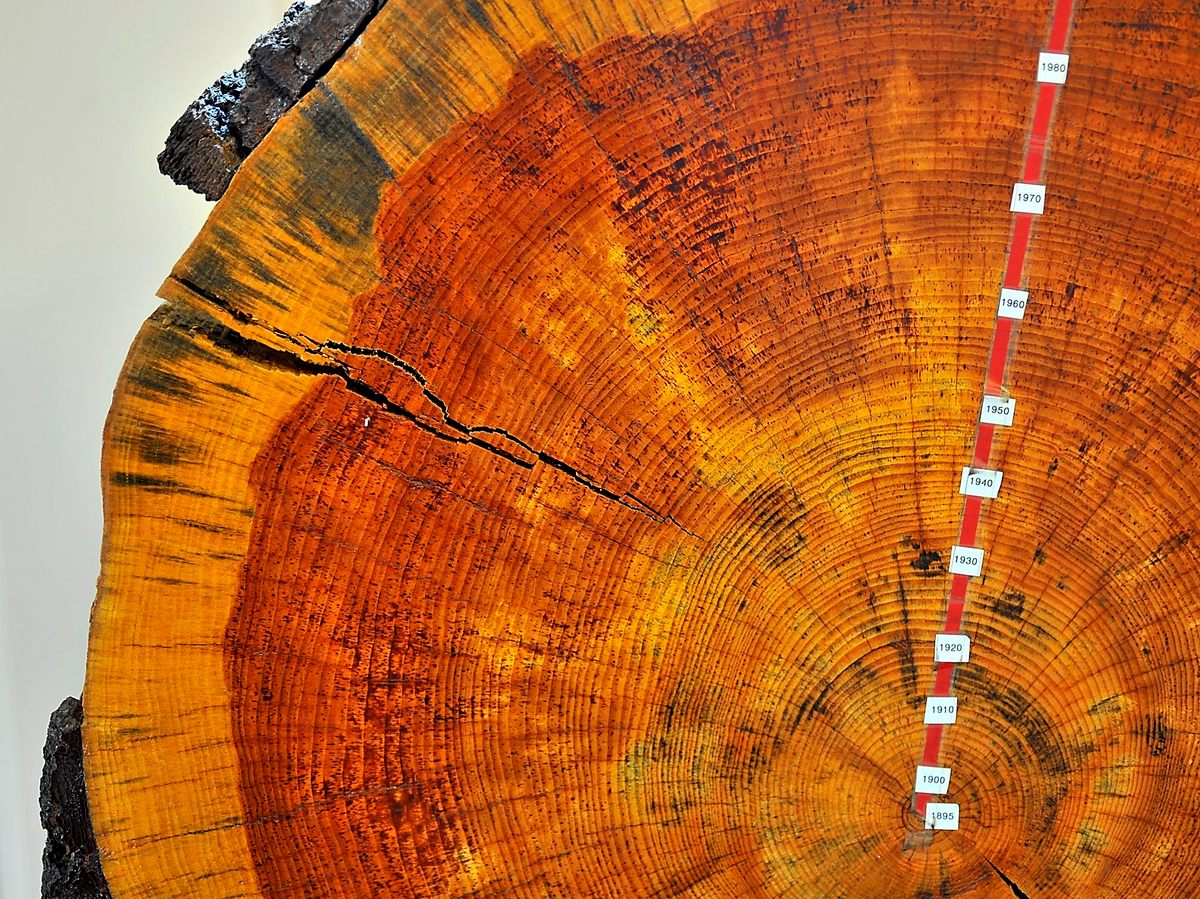

It was Jeff McCarthy, a roofer who grew up here in north-central Maine, who first told me that I should come here to look for the last king pines, trees that were marked by surveyors for the king centuries ago. McCarthy grew up playing in sporting camps—rustic resorts that are a treasured Maine tradition—near The Hermitage. In the 1990s, he and his friends would try to wrap their arms around the preserve’s larger trees. Sometimes, even three of them together couldn’t complete the circle. When wind felled the trees around the camps, they would count the rings on the stumps: Once, he said, they counted 275, making the tree older than the United States.

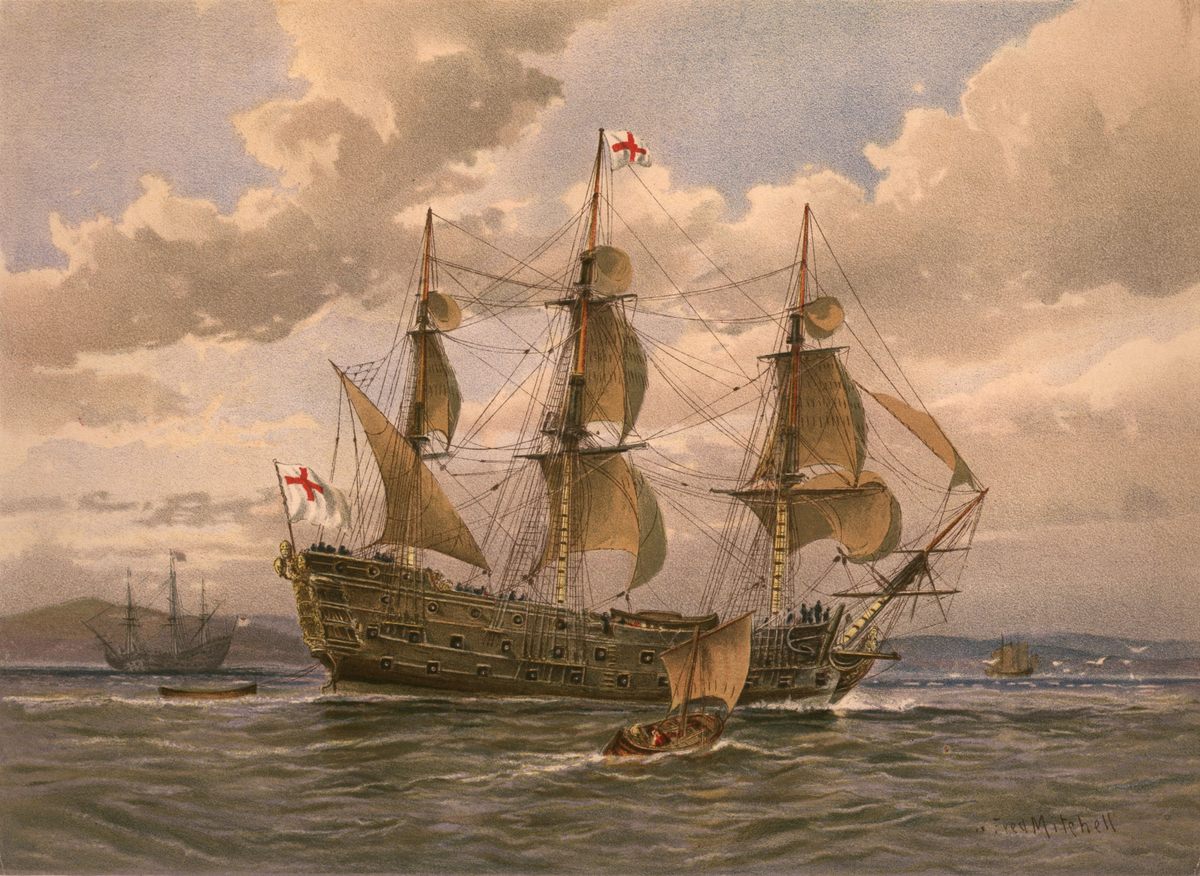

Even earlier, in the mid-1600s, these massive trees caught the attention of the British when they first arrived on the shores of New England. The king’s men, hailing from a country with depleted oak forests, saw one thing when they looked at these tall, ramrod-straight pines: masts for their navy.

“Masts, in the days of wooden ships, played a far greater part in world affairs than merely that of supporting canvas. They were of vital necessity to the lives of nations,” wrote William R. Carlton in a 1939 New England Quarterly article. Canvas was easy enough to produce, but a tree worthy of becoming a mast took centuries to grow. Some British ships needed masts of 40 inches in diameter, a resource hard to come by in Europe. Before colonization, the British sourced their masts from the Baltic, but even those trees rarely topped 27-inch diameters.

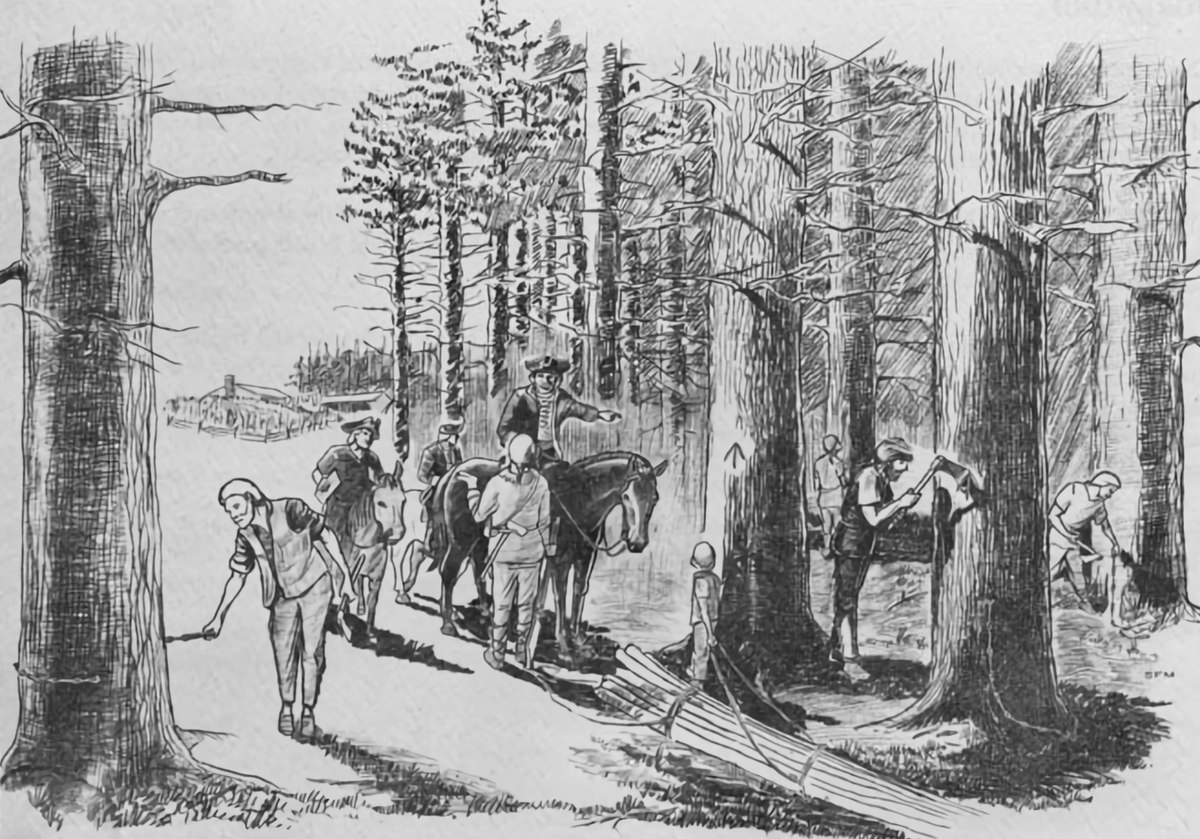

When wars cut off British access to the Baltic region in the 1650s, the king turned in earnest to the forests of the New World. He appointed a surveyor general, who directed laborers to tramp into the woods and mark all trees with a diameter over 24 inches with a “broad arrow,” the official mark to denote the king’s property, made with three blows of a hatchet. This history is indicative of all-encompassing British claims of ownership of the land that belonged to Native people, says Mark Berry, strategic leader for the Maine Nature Conservancy’s forest conservation initiatives. Lumbermen hustled these so-called “sticks” down rivers and onto special, longer-decked boats to carry them across the sea. If you were not one of the king’s men, cutting down one of these trees would incur a hefty penalty—a fact that fomented discontent among colonists in the years leading up to the Revolution. Some New Englanders felled the king pines illegally and then spirited them through their sawmills to hide the evidence; according to Carlton, if you look under the roofs of many colonial houses, you’ll see boards cut at 23 inches, just under the dimension that would reveal they came from a tree claimed by the king.

But trouble still bubbled up around these pines: some colonists bristled at British control of their resources, and their discontent spilled over into mobs and riots. The most dramatic example of this discontent was 1772’s Pine Tree Riot in Weare, New Hampshire, which predated the Boston Tea Party by a year. King’s men caught a group of lumbermen with contraband logs, and the lumbermen retaliated by beating one of the men with long poles. “They made him wish he had never heard of pine trees fit for masting for the royal navy,” wrote historian William Little in a book about Weare history. This revolt inspired the Pine Tree Flag, flown during the American Revolution and later adopted by New England secessionists and conservative groups alike, including some who stormed the United States Capitol in January.

More than 250 years after the New Hampshire riot, a handful of the last trees marked with the king’s broad arrow still stand tall in Maine’s remote forests—or so some locals claim. No one can say for certain that there are no king pines left anywhere in the Maine woods, but experts are skeptical.

“I’ve heard speculation of people seeing the mark of the king’s arrow, but I’ve never seen one, I’ve never seen any documentation of that,” says Jan Santerre, an urban forester at the Maine Forestry Service. Most of the state was logged several times throughout the 19th and 20th century. Trees were sent to the sawmills lining Maine’s rivers, where they were processed for lumber, paper, shipbuilding, and other industries. Even today, logging trucks trundle along the roads in this wilderness, and outside protected areas, stacks of cut trees wait like toothpicks under swinging machinery.

“We lost the vast majority of our old forest. We have very little old forest left in Maine at all,” says Berry. One percent of Maine’s forests are considered old. And of that sliver, only a fraction has never been harvested.

The Hermitage, the preserve where I ventured to look for the king pines, belongs to that rarest of categories: an old-growth forest. No one knows why it was spared first by King George and then by loggers. Its remote location might have something to do with it—it’s close to a wilderness considered the most difficult and undeveloped part of the Appalachian Trail. In the early 20th century, the Hermitage land came under the ownership of a lumber company that used it as a sporting camp until the 1929 stock market crash. Now, the National Park Service administers the preserve as a National Natural Landmark.

Leaving the path, I hiked up a hillside mushy with old leaves and sprills, picking past toppled, lightning-split trees, and walked among the massive trunks to look up at what the king’s men would have seen and claimed ownership of centuries ago. I walked from tree to tree, wrapping my arms around one of them and finding my hands barely able to make it halfway around. I craned my neck up, looking for the brute mark of the king’s surveyors. I knew that finding one was unlikely. Tree scars heal, so even if one of these pines had caught the interest of the king’s men, the bark might have grown over the wound in the intervening centuries.

And even pines that never met a logger’s axe or saw have something else to fell them: time. White pines generally have an upper age limit of 400 years, but wind and weather can kill them sooner. Indeed, dead pines littered the forest floor of The Hermitage, their insides soft with decay. These fallen trees are an integral part of old-growth forests. Ancient, towering trees are awe-inspiring, says Berry, but if you know how to look, the ground cover of an old forest can be even more impressive.

“There are huge pines [in Maine’s old-growth forests], but also gaps and regeneration and other species and younger trees there as well,” says Berry. “I think what a lot of people might imagine when they think of an old-growth forest is a stand of old trees. Where you’re walking among big trees with big trunks and that’s it. But what you have instead is a forest where trees have been dying for hundreds of years.”

These pockets of old-growth forest allow researchers to study rare lichen species, deep-burrowing wood beetles, and other flora and fauna that once flourished all over Maine. Such undisturbed forests, where dead logs in the groundcover may date to the 1600s, provide a detailed look at how such environments function without human intervention, which in turn can help forestry scientists—and even the timber industry—develop better strategies for managed forests.

Santerre says that trying to put a monetary value on these old-growth forests is nearly impossible. When you take into account wildlife support, carbon sequestration, and other benefits the trees provide, their worth “is so astronomical that it’s almost unbelievable.”

Santerre’s words lingered in my thoughts as I searched through The Hermitage for the king pine, my clothes sticky with sap after pausing to sit on a felled trunk slowly returning itself to the earth. The mighty tree—if it even still exists—eluded me. But I later learned that there is one king pine, of a sort, still in Maine.

In the 1960s, a forester found a king pine dying in the wilds of Aroostook County, more than 100 miles north of The Hermitage. He cut it down and brought it to a logging museum in his nearby hometown, Ashland. The museum is open limited hours these days, but a chunk of the once-mighty tree, its broad arrow scar still visible, now sits in a nearby gazebo built to shield it from the elements. Drive down Garfield Road in Ashland, and you can see this last remnant of a different time, when mighty pines ruled Maine’s forest.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook