A Chinese Artist’s Humanizing 19th-Century Portraits of Disfigured Patients

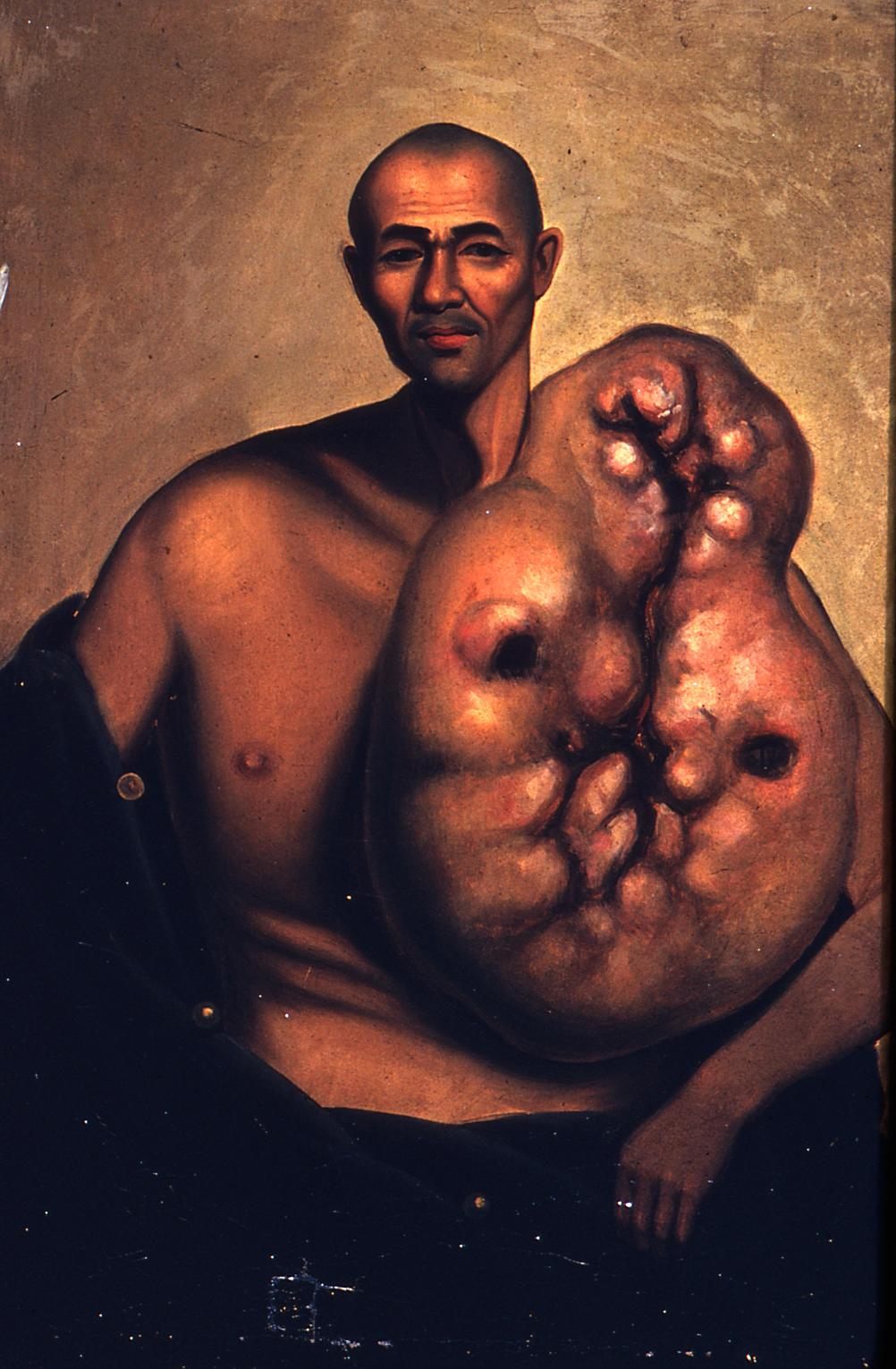

Lam Qua’s paintings depicting people with huge, bulbous tumors remain mesmerizing.

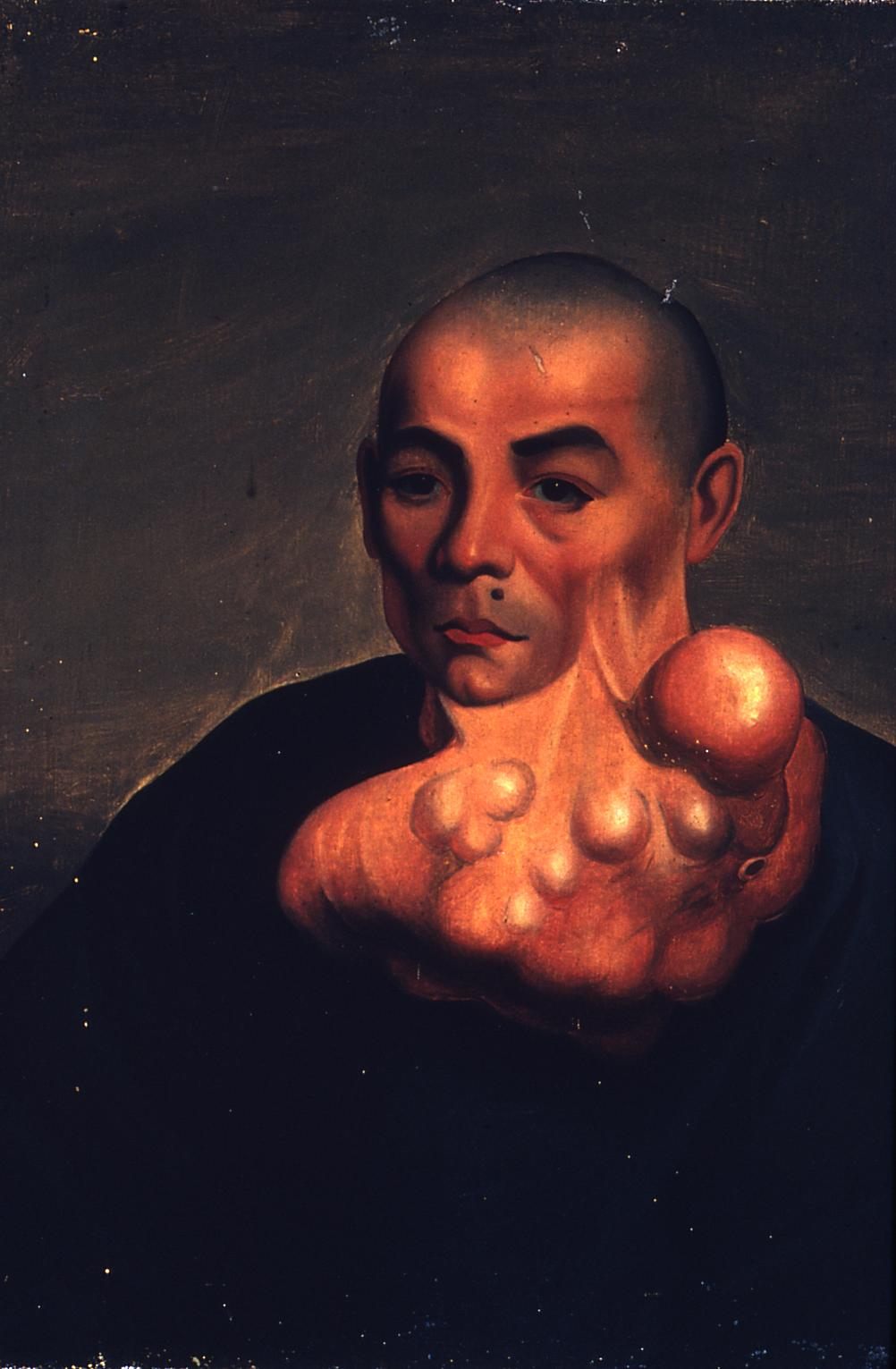

In the basement of the medical library at Yale, there is a box of stones, yellow and ivory and strangely whorled. Nearby are more than 80 portraits of men and women in dark gowns. Their expressions are calm—reserved, even—and they regard the onlooker coolly, despite the pendulous tumors that hang from their arms, noses, and groins. These are relics of a time nearly 200 years ago, when a man intending to collect souls for God found himself instead saving lives for the Emperor of China.

Peter Parker was born in Massachusetts in an era when American trading ships went back and forth incessantly between Boston and Guangzhou, also known as Canton, swapping opium for tea, silks, and other Chinese goods. When Parker graduated from medical school and seminary at Yale in 1834, he felt a call to go to east. He would found an eye hospital in China, he decided, where modern medicine’s miracles would convince patients of Christianity’s power. They would literally see the light, and become Presbyterians.

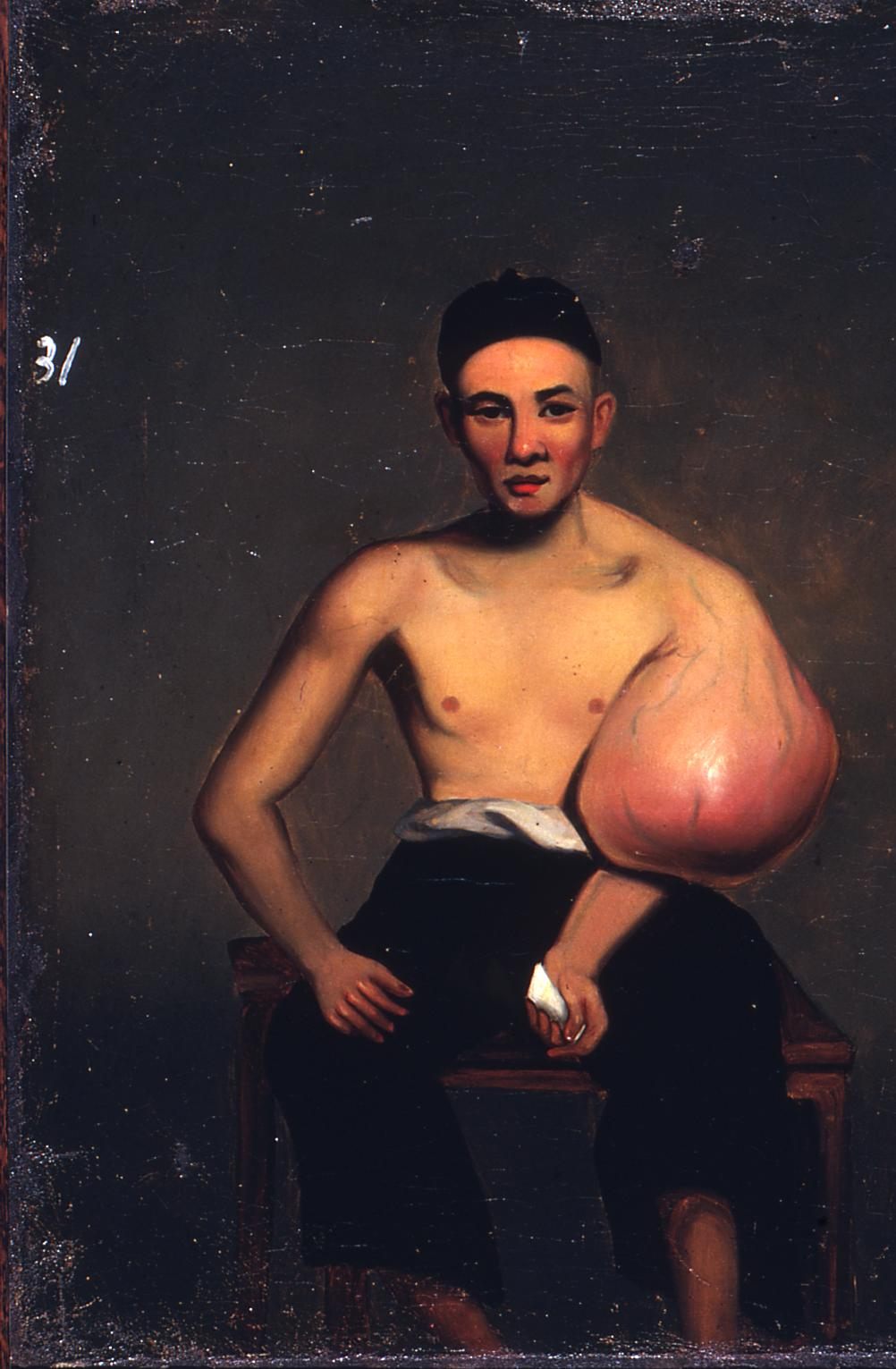

That was the plan, at least. In the cramped alley where the hospital had its clinic, Parker did start out as an eye doctor. But patients with other problems began to appear out of the throngs in the foreign settlement’s streets. At the time, surgery was not often performed in China, and these people had tumors grown out of control, ranging from the size of turnips to small children. Woo Kinshing, aged 49, Parker wrote, had a two-foot growth on his chest the shape of a cello. When it was finally removed, in an operation that took 16 minutes, it turned out to weigh 15 pounds. There was no anesthesia, as the surgical use of ether had not yet been discovered; when people asked Parker for relief, they were facing an ordeal that is hard to imagine. And yet they came, thousands and thousands of them.

More than 40,000 patients were treated at the Canton Hospital over the next two decades, including fishermen, shoemakers, and merchants from every class of Cantonese society. Parker recorded their cases in his journals and published articles in missionary newspapers, hired assistants, taught local medical students. And, at some point very early on, he appears to have run into someone who would have been a neighbor, the renowned portraitist Lam Qua. In a transaction whose exact details have been lost to time, he commissioned the first of the paintings.

Today, thousands of miles away from home, the paintings have outlived their commissioner, their maker, and their subjects. And yet, they are consistently requested by the Yale library’s patrons, from historians to filmmakers to journalists. They were even summoned forth by a medical school professor this year. “[They] remain a source of intense fascination to anyone who views them,” writes Ari Heinrich, a scholar of Chinese cultural studies in The Afterlife of Images, one of the few books that addresses the paintings. At the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, which is planning to put a Lam Qua tumor portrait on display for the first time in more than 25 years in 2021, curator Gordon Wilkins muses about them, “There is something that’s quite eerie, but also quite beautiful.” What is behind their enduring power to obsess?

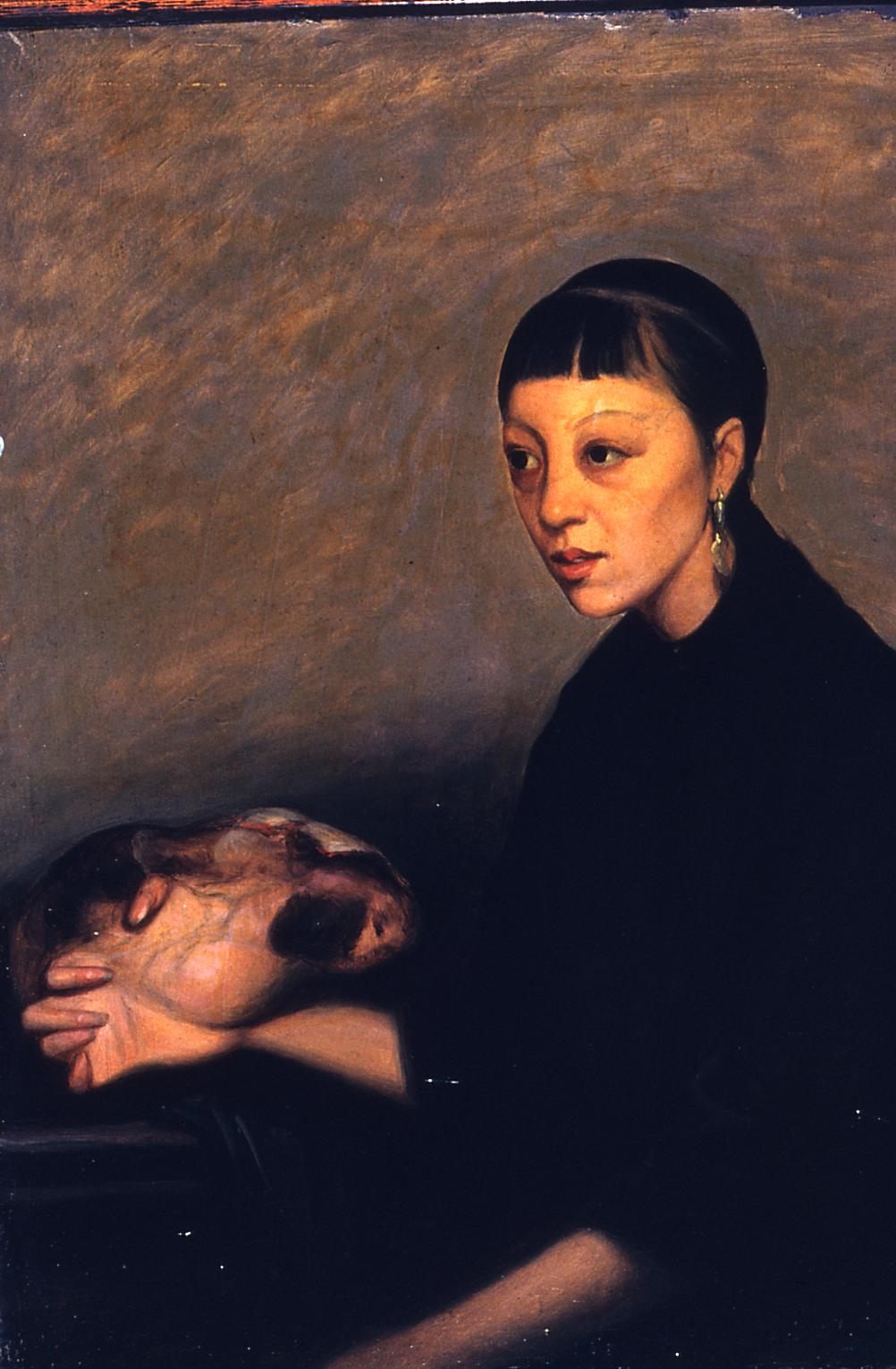

In the Yale collection, a silver earring dangles by the throat of the young woman labeled Number 6. She wears bangs cropped fetchingly high across her forehead, but her right hand, with its beautifully kept nails, emerges from a black-and-pink mass the size of a housecat. A fault line of lava red creeps across its surface. She opens her mouth as if to speak.

In the early 1990s, Stephen Rachman was working in the Yale medical history library when a librarian friend tapped him on the shoulder. “Do you want to see something gross?” he whispered. Rachman, who was a graduate student at the time, left the reading room and descended with the librarian to the storage area. “I’m the kind of person who doesn’t turn that kind of thing down,” reflects Rachman, now a professor of English at Michigan State University.

They unlocked a metal grate and entered the dusty stacks, making their way back to an ancient cabinet. On the inside of the door hung a yellowed piece of paper with a poem. Rachman leaned in to read it. Peter Parker’s pickled paintings / Cause of nausea, chills & faintings / Peter Parker’s putrid portraits / Cause of ladies’ loosened corsets… Peter Parker’s pics prepare you / For the ills that flesh is heir to.

The irreverent couplets of some long-ago writer were correct in at least one particular: Within was the collection of paintings. The box of stones—bladder stones, it turned out, that been removed surgically by Parker and his colleagues—was on top. The cache of portraits had grown crepuscular as the oil pigments aged and darkened, but the nameless patients still looked out from the twilight of China’s last dynasty with that uncanny directness. Rachman’s thesis was on something else altogether. But he could not get them out of his mind.

A few years later, he happened to visit the 300-year-old Guy’s Hospital in London, where paintings from the old teaching collection were on display. Among them were several that sent a thrill of recognition through him. “I knew exactly what they were. You don’t forget these things,” he said. He began to dig. In addition to the 84 tumor paintings at Yale, there were 27 in the collection at Guy’s, 4 at Cornell, and one at the Peabody Essex Museum, as well as numerous watercolors at Harvard and the Wellcome Institute in London. Yale’s library also had Peter Parker’s journals. Rachman spent hours poring over them on a microfiche machine, putting names and stories to faces. Along the way, he learned about the works’ creation.

The artist Lam Qua—urbane, talented, prolific—was one of the most acclaimed portraitists on the South China coast, and initially he painted the pictures for free, according to Parker, in recognition of the hospital’s decision not to charge, as well as in appreciation of Parker’s taking on his nephew as a student. Later, he was paid at least once for his services. Parker was likely to have had multiple motivations himself: In the beginning, he may have been thinking of using the pictures to teach medical students. They may also have been intended as encouragement; visitors to the Canton Hospital reported that the waiting area featured paintings of patients before surgery and after.

And that presents a mystery tied to the pictures’ lasting interest: Only a single example of a post-surgery painting is known to exist today. Po Ashing, in his first portrait, is seen against a wall, exposing the globe of tissue that has engulfed his left arm. In the second, he stands on a shore with mountains in the distance, erect. The arm and its growth are gone. The wound has healed well. He looks much less remarkable than before. Is this normalcy why we know of no other surviving post-surgery paintings? Parker’s conversion numbers were disappointing to his American missionary board backers—Protestantism, it turned out, incited considerably less enthusiasm than medical treatment. To raise his own funds for the hospital, Parker took the portraits on a successful fundraising tour up and down the East Coast and across Europe. One missionary society even gave money in exchange for the promise of paintings for their own collection. Perhaps the portraits’ value to him, and to the medical schools where some have been preserved, lay in the patients’ pre-operative strangeness.

There is something about the paintings that goes beyond gawkery, however. “I can’t speak for all humanity. I know some people find them stomach-churning,” Rachman says. “But to me … if you’re the kind of person who actually thinks maturely about human affliction rather than just turning your head away from it … these people are fascinating.” He reflects on the intensity of preparing for major surgery, the fear, the pain, the distress. At the thought of posing for a portrait first, he trails off. “It’s almost like watching someone get ready for battle.”

“There’s something going on here that’s really way beyond ordinary clinical portraiture,” he says. “People have turned them into specimens. And they refuse it. They resist.”

The paintings have an oddly familiar quality. In fact, they are in a style similar to Regency-era portraits of English aristocracy by Thomas Lawrence. Posing with rumpled cravats and pink cheeks before a stylized landscape or a moody wash of black and grey, Lawrence’s subjects’ expressions are carefully neutral, while in the distance a winding river or a grove of trees hints at a greater world within. “There’s meant to be some kind of resonance, a visual encyclopedia of that person’s essences in the environment,” says Ari Heinrich, who learned of the patients as a graduate student and is now a professor at UC San Diego.

Lawrence’s contemporary, George Chinnery, was the premier English portraitist of the British Raj. He fled his debts and responsibilities in India, arriving on the South China coast in 1825 as Lam Qua was beginning his career. While the nature of their connection is not clear—was Lam Qua his student? Or just a savvy competitor and imitator?—what is clear is that Lam Qua’s Western-style works draw heavily on Chinnery’s lineage of British portraiture. That feeling of recognition comes from the skillful use of a familiar visual language.

The paintings were seen by hundreds, if not thousands of viewers—not just patients and missionaries but both houses of the U.S. Congress, the archbishop of Canterbury, and the king and queen of France. The otherwise ordinary people in the portraits extravagantly encumbered with disease likely broadcast something to Western viewers about their nation, says Heinrich. In the west, China has stood for many things over the years; as historian Jonathan Spence writes, to outsiders it has embodied the exotic and the terrifying, the backwards and the advanced. Missionary writers, Parker’s contemporaries, often expressed the idea that something ailed China, body and soul, that Christianity could cure. “Not only the minds of the people, but their bodies also, are distorted and deformed by unnatural usages,” held the Chinese Repository, a missionary gazette.

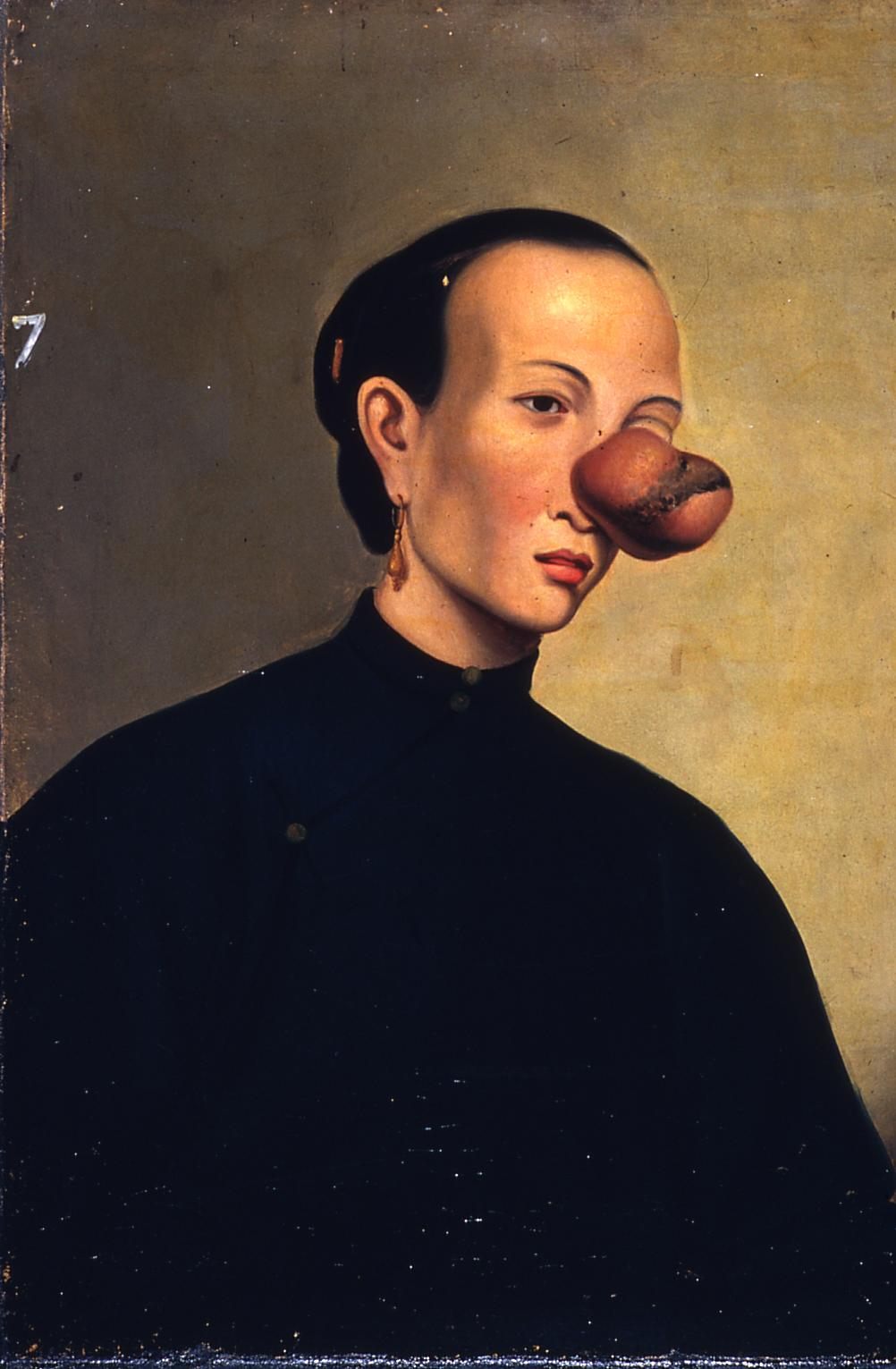

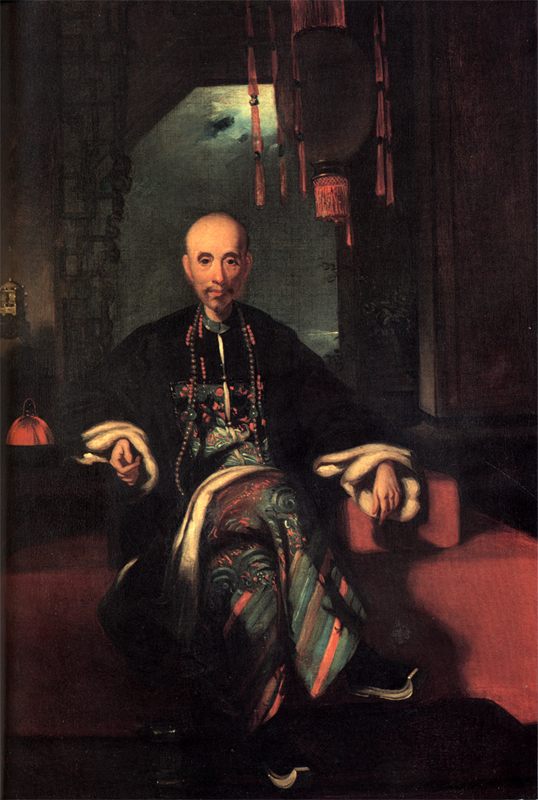

Yet despite this, the paintings evade pity. Nor do many subjects seem particularly ill. A mandarin labeled number 38 in the Yale collection, with a red button shining in his cap, is watching something we cannot see, his pale brown eyes calm and his relaxed face faintly jovial in its lines. There is a gentle fearlessness in this face; this is someone to whom no harm will come. He appears almost divorced from the lumps protruding from his left cheek. The pink knob highest in the mass echoes the red button, and on the growth’s surface blackened pustules are rendered with a blurred brush, suggested rather than described. A single dab of white indicates the shining skin, stretched taut over the swollen tissues. Overall the feeling is not of a medical precision, but rather of an almost impressionistic capturing of the sense of the person.

Lam Qua himself may have known the patients more intimately than Parker, who cared for them tenderly but was still separated by barriers of culture and language. And he may have seen a delicious irony in the whole project. When one takes a form that has been applied to the vanity of the wealthy and applies it to surgical patients, it feels almost subversive.

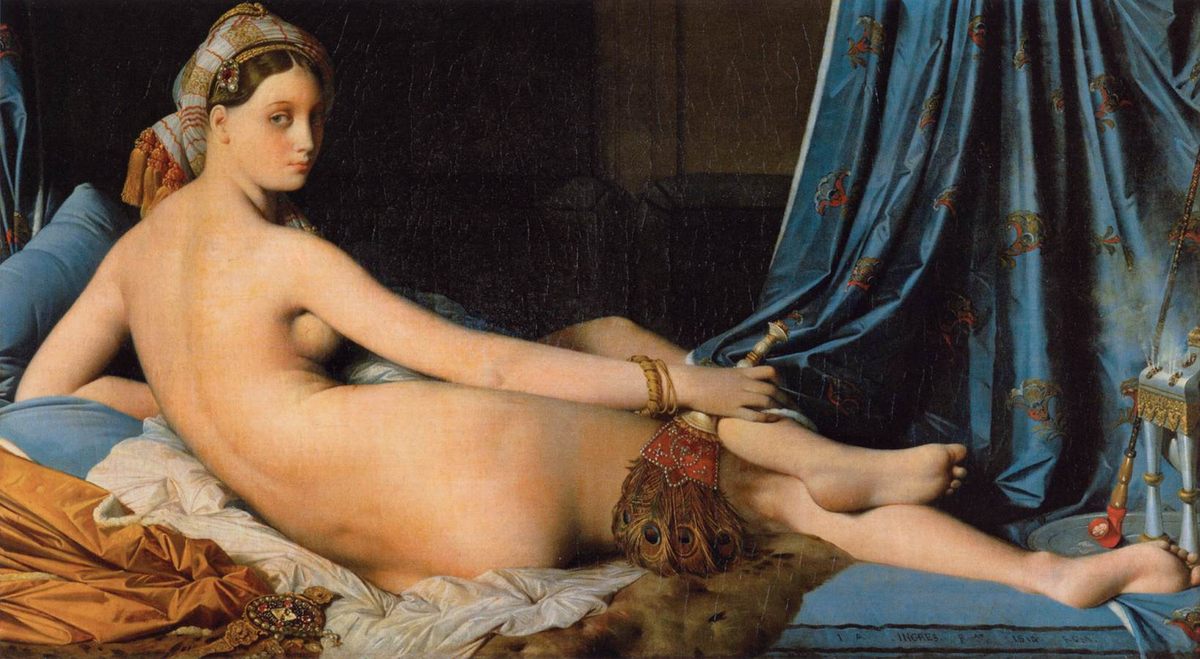

In Ingres’ painting La Grande Odalisque, a famous 19th century Orientalist fantasy of a Turkish concubine, a nude woman looks back over her shoulder at the viewer, her rear exposed in full view, her anatomy somehow strange and elongate—some critics have remarked that the Grand Odalisque has two too many vertebrae. Lam Qua painted a copy of that work for another client, perhaps before he collaborated with Parker. In one of the tumor portraits, Lam Qua sets up an echo, Heinrich suggests. Lew Akin, a young woman with a tumor on her buttocks, sits with her voluptuous growth exposed and regards the viewer with the same enigmatic backward glance.

At the Peabody Essex Museum this summer, I met up with Gordon Wilkins (he has since moved positions) who took me into a basement where wooden statuettes and golden filigree boats waited on shelves against the walls. Lying on a table, carefully covered with cardboard, was the museum’s Lam Qua tumor portrait. A man with beautifully formed eyebrows sits looking out, a sac of goose egg-like tumors hanging from his left cheek. This is a duplicate of a painting that is also in the Yale collection, which I had visited a year before. On that visit, when I walked into the medical history library’s reading room, and saw the five paintings I had asked to see lined up, I felt a wave of excitement.

The paintings may have been produced for utilitarian purposes, but they have become great works of art. Wilkins compares them with the photographs of Rosamond Purcell, whose bewitching chronicle of burned books, preserved natural history specimens, and other slightly creepy subjects have transfixed viewers for years. “[She’s] made a career of photographing things that to the outside world would seem unphotographable,” Wilkins says. “She elevates that to the level of beauty, which is true of the Lam Qua portraits.” Their immortality comes from the way they erase the distinction between the viewer and the subject.

Indeed, you can cross the line at any time. I learned about the paintings when I was a patient at the Canton Hospital myself. The institution founded long ago by Parker was eventually absorbed into a large public hospital system in Guangzhou, where, on the day I had my blood drawn for some tests, the person who was supposed to take samples to the lab was away. I carried the hot vials of my blood against my stomach across a courtyard into a curious old building. Inside it was dim and high-ceilinged. There was wainscoting, the dark wood paneling receding back along the halls like in a New England sanatorium. I had seen nothing like it in south China, a place of sulfurous sunlight and seething tropical greenery even in this megacity of 13 million people. After I delivered the blood to a surprised pathologist, I went back through the darkness to the entrance. Beside the door was a plaque mentioning Peter Parker, which led me, after a little quick Googling, to the paintings. That was several years ago, and now they are familiar to me, even beloved.

The growth that they found inside me turned out to be nothing serious. Bodies are mysterious; sometimes they surprise us. But now, years later, having followed the thread to the 84 long-dead patients whose faces still haunt my imagination, I often think back to that moment, when I didn’t know what would happen. “There’s a strange identification between the viewer and the subject,” Wilkins would remark years later, as we gazed at the man in the painting. Peter Parker’s pics prepare you / For the ills that flesh is heir to.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook