A Trove of Sad, Funny, and Familiar Stories From the 1918 Flu Pandemic

A UCLA librarian has built a remarkable collection of century-old letters, diaries, and photographs.

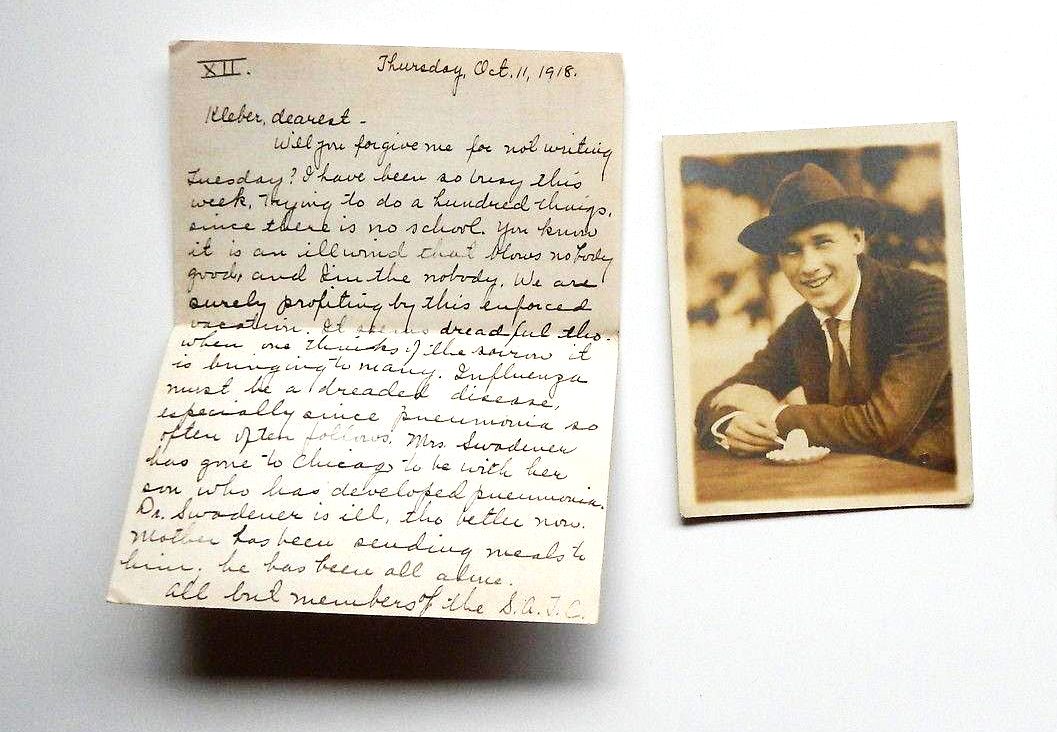

On November 21, 1918, an Indianapolis schoolteacher named Hildreth Heiney wrote to her deployed fiancé, Sergeant Kleber Hadley, about the sudden appearance of face masks in response to the global influenza pandemic. “Yes, I wore one, and so did everybody else,” she wrote cheerfully. “There were all kinds—large and small—thick and thin, some embroidered and one cat-stitched around the edge.” An order to wear masks in public had just taken effect in Indiana, and Heiney seemed to take it in stride. “O, this is a great old world!” she went on, poking fun at funny-looking mask-wearers. “And one should surely have a sense of humor.”

Heiney’s colorful letters are part of a remarkable collection of “personal narratives, manuscripts, and ephemera” about the 1918–1919 flu in the biomedical library of the University of California, Los Angeles. There are letters from California mayors about influenza death rates; Thanksgiving postcards written by children; and laconic Yankee diaries, such as this tragic entry from a Mrs. Slater: “Rained. Spent the day home. Veree Clark died of influenza. E.F. King’s wife funeral. Buzzed wood home.”

Russell Johnson, a curator of history and special collections for the sciences at the UCLA Library, says that he created this intimate collection “from scratch.” Originally slated for a career in behavioral neuroscience, Johnson ended up in library school instead, where he studied the history of neuroscience and medicine. “I fell in love with cataloguing,” he says.

Today, the influenza collection includes boxes of original letters, diaries, and photographs from 1918 and 1919. In these century-old artifacts, civilians and military personnel recount harrowing and sometimes humorous experiences of life in the shadow of influenza. Many of them have special resonance in the time of COVID-19. Atlas Obscura asked Johnson how he amassed the collection, what unique lessons can be learned from these personal stories, and what became of a soldier named Alton Miller.

How did you start putting this collection together?

The UCLA biomedical library covers the history of medicine and science. Contagious diseases, such as smallpox and cholera, have always been part of what we collect. About 10 or 12 years ago, with the anniversary of the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic coming up, I wasn’t seeing much in the way of personal letters and diaries. So I just started buying them individually, a lot through eBay. Now they’ve become very competitive to get on eBay, because other people are looking for them.

Who’s selling you personal letters and diaries from 1918?

Sometimes people come into big troves of letters and diaries [through family]. Or they’ll find things in storage lockers that were sold off, or estate sales. I never go to estate sales myself because they’re so competitive, but I depend on other people to go and sell to us. For example, once people saw that we were creating this collection, a bookseller up in Berkeley sold us the album of the complete Alton Miller correspondence. Booksellers love to find stuff for us. They like building collections with institutions and collectors.

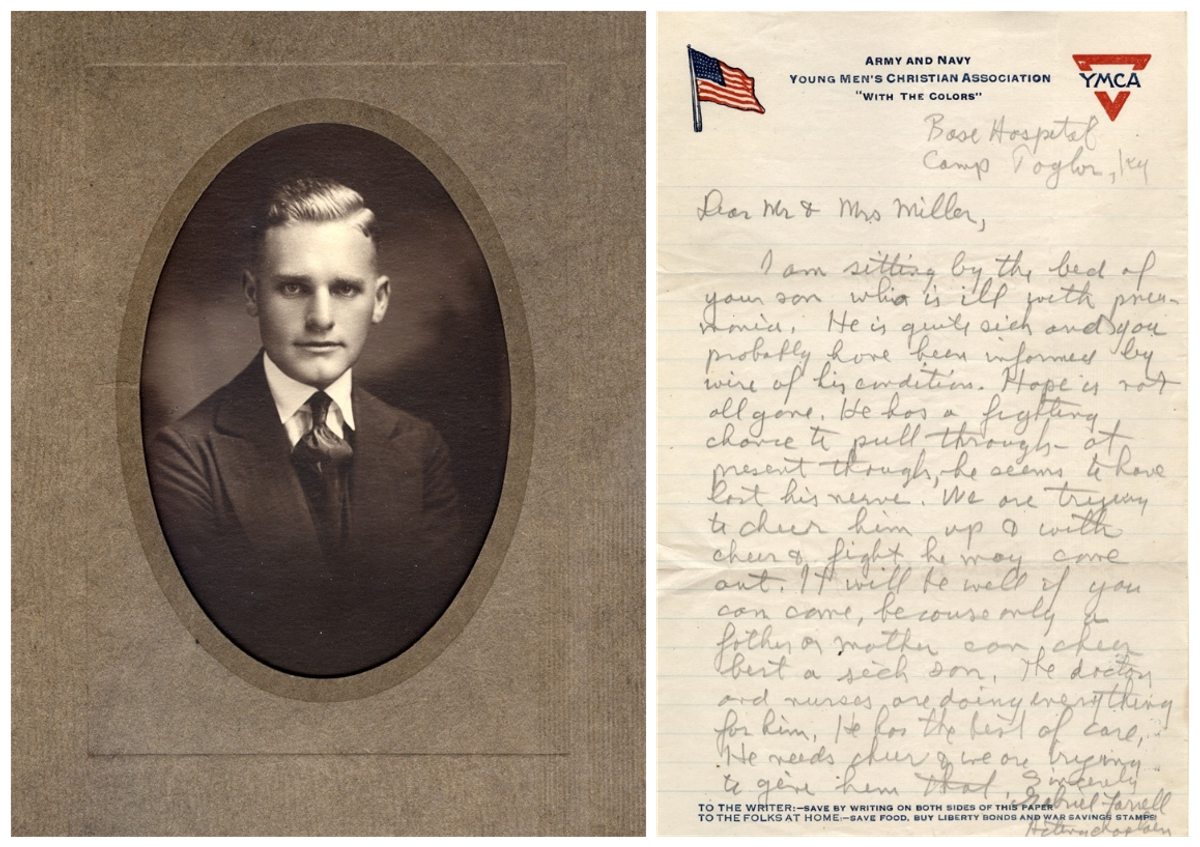

Can you describe the Alton Miller correspondence?

It starts with this young man who is a chauffeur or driver. He’s inducted into the army and starts off at Fort Dix in New Jersey. He writes home to a sister, Adah, and to his mother and his father. We don’t see their letters, so I think what we’re seeing is probably what Adah held onto. Alton transfers to Camp Zachary Taylor, in Louisville, Kentucky, and writes to his father on October 5:

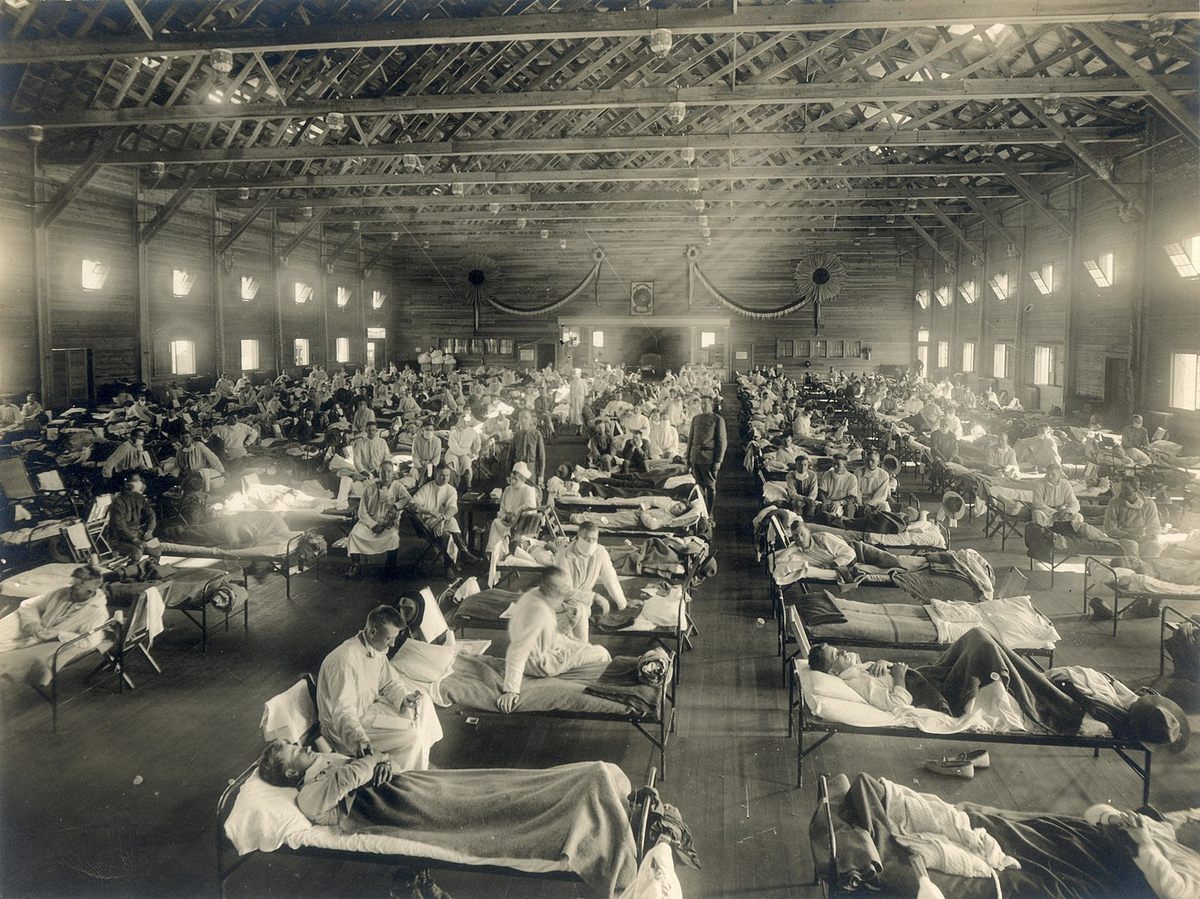

“Don’t get frightened but I have had the influenza for four days but I have not let the authorities know about it.… Our hospitals are overcrowded here and I think in another week the whole camp will be quarantined. The treatment you get in the hospitals is absolutely rotten, they say. It is so crowded that you don’t get enough to eat and it is very dirty and most of the nurses and attendants have got it, too.... Once get in you have a hard job getting out.”

Then he writes letters to his sister that paint a little more serious picture than what he told his parents:

On October 5: “There are nearly 10,000 cases down here and 22 deaths were added today. I don’t know how many deaths there are all together.”

On October 6: “Adah, ambulances are running in every direction out here. They haven’t closed the camp yet, but I think they will soon. I am coming in good shape. I am very glad I did not report it and go to the hospital. They say you are lucky if you get out alive once you get in.”

And then you see a letter from a friend and from the chaplain essentially saying to the parents, “You should come, your son is in the hospital with influenza.”

Then you see an October 11 telegram from the army, saying: “Your son Alton Miller died at base hospital at one o’clock today. Wire me if you want remains shipped at government expense and to whom remains will be consigned.” It’s heartbreaking. There’s a couple of condolence letters, and then this medal at the end that was awarded the year after the war, by the community, to Alton’s mother.

How come there are so many letters available from this time?

This was during World War I, and soldiers could send letters for free, indicated by the label “soldiers’ mail.” You also see some letterheads from such institutions as the YMCA, or other organizations that provided free stationery to soldiers. Soldiers were encouraged to write. The expectation was that you do your day’s work, and then at night you sit down and write two or three letters, even when overseas. The amount of mail that went back and forth between soldiers and families is just incredible. It would be like texting today.

What can you learn from these personal narratives that you can’t really glean from reading the news and public announcements from the time?

You learn a lot of particulars of how people dealt with each other. It’s the very personal, very immediate experience that you don’t see in the news or an official report. People are talking about the inconveniences of theaters and shops being closed, or people wearing masks and how funny, how odd they look. Then it becomes commonplace because everyone is doing it.

Then there’s the day-to-day life into which influenza was intruding. When people were talking about others dying, they would distinguish whether it was with the influenza or something else—because everything else was still happening, like it is now. We’re so focused on coronavirus, and yet people are still having babies. People are still dying from heart attacks and cancer. Sometimes you might forget that this is just a component of our lives, or their lives in 1918.

What did you learn from these letters that surprised you the most?

In many letters, like that diary of Mrs. Slater, or the letters from Hildreth to her fiancé Kleber, was how much the influenza became a part of their lives—but it just seemed to be one more part of their lives. There was tragedy, but they overcame it. And the humor that they could use! Hildreth was a schoolteacher. At first, when the schools were closed, she called it a vacation: “The four weeks of vacation as a result of the epidemic of influenza almost cured me of any desire to teach school,” she wrote. There’s still this time to joke with her fiancé. Even though this horrible stuff was happening around them, life went on.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook