The 1945 ‘Liberation Concert’ Played by an Orchestra of Holocaust Survivors

The performance took place at St. Ottilien Archabbey, a Benedictine monastery that became a hospital for Jewish displaced persons.

On May 27, 1945, U.S. Army Private Robert Hilliard set off from his base near Munich into the Bavarian countryside. Nearly one month had passed since Allied Forces liberated Nazi Germany and the 19-year-old soldier was heading to a concert organized by and for Holocaust survivors. Billed as a “liberation concert,” such an event so soon after the war’s end seemed almost frivolous to him. But he thought it would make a fine feature story for the Army newspaper he edited. And, he would quickly learn it was anything but frivolous.

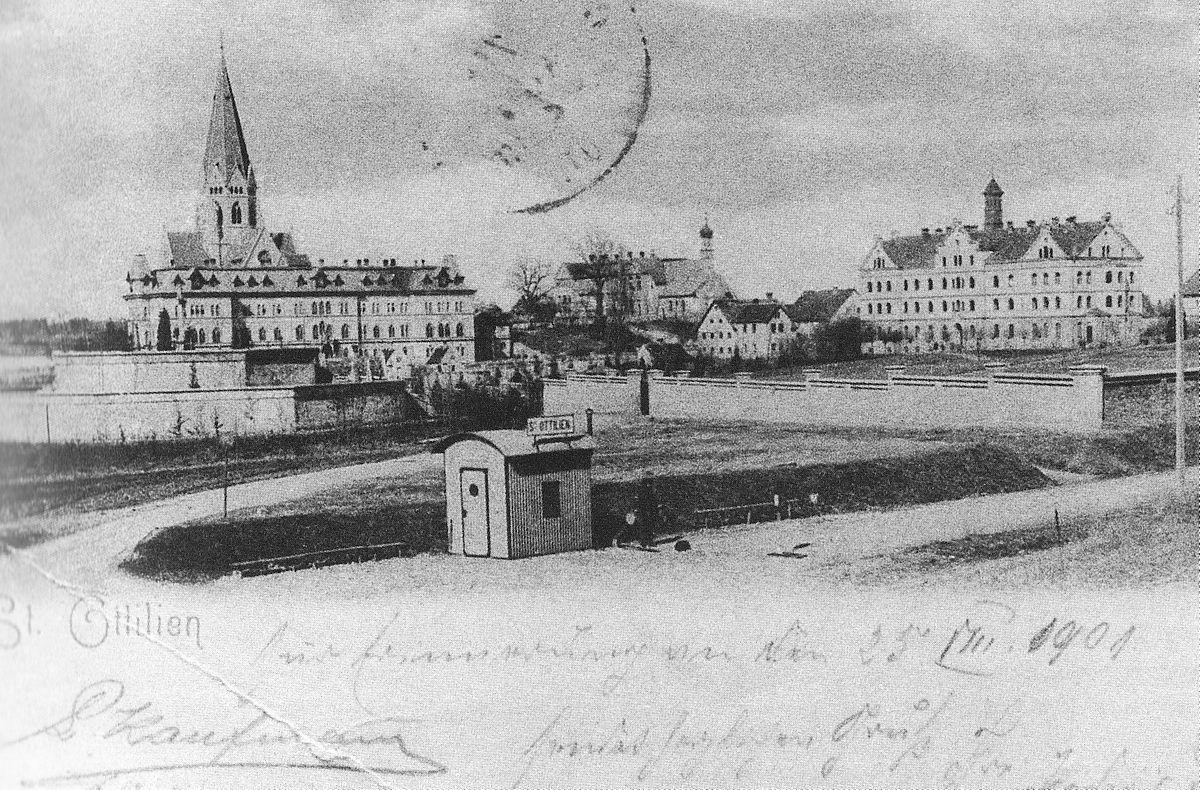

Hilliard’s destination was St. Ottilien Archabbey, a Benedictine monastery that was home to a new hospital for Jewish Holocaust survivors. The German military had ousted the monks during the war and turned St. Ottilien into a hospital for German troops. When the U.S. Army took over supervision of the monastery in early May 1945, it became a camp for displaced persons, or DPs, as the survivors were known to those overseeing their resettlement.

The walled monastic complex rose from rolling green farmland. Hilliard drove through a stone-walled entrance and parked on the edge of a wide green lawn. A stage of mismatched wooden boards was covered in a patchwork quilt of bedsheets and parachute cloth. The survivors in the audience resembled stick figures—emaciated, pale, expressionless. Some were so weak they had to be carried from their hospital beds. Off to the side, Hilliard observed a mix of civilians and soldiers—most likely, Germans and Americans—casually talking and smoking cigarettes.

The juxtaposition of captors, captives, and liberators was jarring to Hilliard. In the camps, Jewish musicians played for Nazi soldiers in mess halls and on train platforms as fellow prisoners of war arrived. Now, still dressed in their striped uniforms, the musicians played anthems of the Allied Nations and Jewish folks songs for an estimated audience of 400 people.

Hilliard described it as, “a concert of life and a concert of death,” one in which “most of the liberated people were too weak to stand; a liberation concert in which most of the people could not believe that they were free.” Eventually, the group of musicians would come to be known by various names, including the St. Ottilien Orchestra, the Ex-Concentration Camp Orchestra, and the Representative Orchestra of the She’erit Hapletah, a Hebrew phrase translating to “surviving remnant.”

Hilliard’s recollections from his memoir, Surviving the Americans, turned over in my mind when I visited St. Ottilien in September 2018 for a concert commemorating the 1945 event. Today, as in 1945, the concert was intended to convey sentiments of remembrance and reconciliation in turbulent times, organizers said. The musicians were from Tel Aviv University’s Buchmann-Mehta School of Music, Israel’s leading classical music academy, and many were descendants of Holocaust survivors. Accompanied by the world-renowned German violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter, they played for an audience of Germans, Americans, and Israelis, some with a direct connection to St. Ottilien.

It was my second visit to St. Ottilien in three months after learning about it in 2017. My grandparents and the uncle for whom I am named reunited there after the Holocaust, and my grandfather was the first chief doctor of the DP hospital. But I didn’t know any of this family trivia until the fall of last year, when I decided to start searching for the grandparents I never knew. In my first visit to the monastery, I felt an instant connection to the place that offered my family refuge after a harrowing period in their lives. I could imagine them walking the same cobblestone paths, minding the ever-present church bells—or possibly cursing them just as I did in the early morning.

At the 2018 concert, I came to understand the 1945 liberation concert as an expression of a particular kind of beauty that comes from overcoming immense pain and sorrow. My heart ached for my grandparents and other survivors as I tried to comprehend their state of mind in this transitional period. Although they were no longer prisoners of war, they nevertheless faced an uncertain future. Anti-semitism in Europe did not end with the defeat of the Third Reich, and some Allies maintained the strict immigration quotas that prevented Europe’s Jews from fleeing Nazi persecution. As such, historians see parallels between the plight of the Jewish DPs and today’s global refugee crisis.

For these survivors, it was a period of renewal, but also an era of continued struggle and conflicting visions for the future. In a speech at the 1945 concert, my grandfather described the surviving remnant’s tenuous state.

“We are free now, but we do not know how, or with what to begin our free yet unfortunate lives,” he said in German, a language he picked up from his captors. “It seems to us that for the present mankind does not understand what we have gone through and experienced during this period. And it seems to us that we shall neither be understood in the future.”

My visits to St. Ottilien to confront the past coincided with the monastery’s own historic reckoning for the first time since the DP camp closed 70 years ago. Throughout 2018, St. Ottilien partnered with Bavarian heritage groups and cultural institutions on memorial events, including an academic symposium and two memorial concerts. With the rise of anti-Semitism and extremist ideologies in the United States and Europe, organizers of the events said it’s more important than ever to remind people of the effects of hatred, especially as the collective memory of the Holocaust fades with the last generation of survivors. The responsibility of preserving those memories from St. Ottilien is passing on to the next generation, many of whom were born at the monastery. A handful attended the 2018 memorial concert, eager as I was to connect with their history.

St. Ottilien today is a different place from when Hilliard first encountered it. Recent additions include a beer garden and a gift shop. But to newcomers, walking along its shaded paths past religious shrines and monks in black robes can feel like stepping back in time, even if the idols have fresh coats of paint and the monks are carrying smartphones.

The grassy site of the liberation concert has been carved into a thin sliver to accommodate new paths. But the two-story building next to it that was a hospital for Jewish patients, with a kosher kitchen in the basement, still stands. Today, it’s a middle school with a sign in front explaining its history—one of several on the grounds marking points of significance from the DP camp era.

From 1945 to 1948, some 5,000 survivors passed through St. Ottilien and more than 400 children were born there as families reunited and new ones began. My grandfather was among the first group to arrive. In late April, with the help of an American soldier, he and fellow survivors obtained permission to turn several buildings in the Benedictine monastery into a temporary hospital.

The monastery was one of many DP camps in Allied-occupied Germany, Austria, and Italy. They were conceived as temporary centers while the Allies and aid groups worked to repatriate Jews to the countries where they lived before the war. But many refugees refused or felt unable to return to the places where they had lost everything. And so the camps evolved as Jews began to rebuild their lives within their confines.

Few of the DP camps were like St. Ottilien, however. Most were housed in former military installations, labor camps, and even repurposed concentration camps. Situated in the lush Bavarian countryside, with modern amenities including a hospital, a gymnasium, and a printing press, St. Ottilien offered a comparatively comfortable setting.

Many survivors arrived with overlapping conditions, such as tuberculosis, starvation, and infectious skin diseases, and some would succumb would to them. Less than a week after their arrival, the first burial was held in a cemetery created for the Jewish survivors on the monastery’s periphery. Despite these cruel twists of fate, the conferral of a proper Jewish burial, presided over by a rabbi, offered an early sign of the restoration of dignity and community to the surviving remnant. An elementary school and a maternity ward came next.

As word spread of the material comforts St. Ottilien offered, the renowned Lithuanian violinist Michael Hofmekler was one of many refugees to seek it out. Also known as Misha, Moishe, and Michel, he was born in Vilna in 1905 to a family deeply involved in music. His career took off in the 1920s and 1930s in Kovno, earning the recognition of the Lithuanian Grand Duke Gediminas in 1932. After the German occupation of Lithuania in the summer of 1941, Hofmekler was forced into the Kovno ghetto with his parents and sister. Only he would live to see the war’s end.

After surviving several massacres that wiped out most of Kovno’s Jews within six months of the German occupation, Hofmekler obtained permission from the ghetto’s Jewish council to start an orchestra. When the Nazis evacuated the ghetto in 1944, he and others were sent to a forced labor camps across Bavaria, where they built bunkers and supplies for Hitler’s army. After liberation, he made his way to St. Ottilien and helped form the orchestra that performed at the liberation concert.

Unexpectedly, Hofmekler also reunited with family at St. Ottilien. His brother Robert had left Europe for the United States in 1938. He was drafted into the U.S. Army and in June 1945, Robert Hofmekler found his brother at St. Ottilien. And 73 years later, a Hofmekler descendant would find his long-lost relative there, too.

Daniel Hofmekler was another brother who left Lithuania before the war. He carried on the family’s musical legacy as a music teacher in Palestine’s growing Jewish community and later, a cellist in the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra. His son, Eyal Hofmekler, was born in Israel and he, too, inherited the family passion for music. Today, he restores musical instruments and accessories. When concert organizers asked him to build an instrument for the program, he was honored, even though he knew little about St. Ottilien’s significance at the time.

Eyal says this year’s concert is a “continuation of the family music tradition,” a legacy that lives on through the student musicians from Tel Aviv University who performed at the concert.

One of those students, the violinist Vicky Gelman, has no connection to St. Ottilien, like most of the musicians. But as an Israeli and a Jew, the memory of the Holocaust looms large in her life. She’s heard the stories from her grandparents and she participates in memorial events each year on Holocaust Remembrance Day, which is a national holiday in Israel. Being in St. Ottilien for the concert brought a new dimension to her experience of the Holocaust.

“We come to the place where everything happened and it’s real, we feel it, we stand on the land,” she says. “It’s not just a regular stage at school or a concert hall.”

The 2018 memorial concert took place inside the monastery’s Gothic church instead of on the grassy plot. On the afternoon of concert, sun streamed through the church’s stained glass windows, brightening its vaulted stone interiors. Purple stage lights transformed the altar into a dramatic backdrop for the makeshift orchestra near the pulpit crammed with music stands and chairs.

German classical music fans filed into the pews, taking seats alongside descendants of survivors. Eli Ipp was an infant when his parents brought him to St. Ottilien. His father was a doctor in the monastery’s hospital. As the young musicians dressed in black took their seats to thundering applause, “my heart burst with pride and tears flowed, to feel and see how history had reversed itself,” says Ipp.

The program began with the same bellow of horns that opened the 1945 concert in Edvard Grieg’s “Triumphal March.” It was the only song from the original program. The orchestra manager Bilha Rubenstein says she and others worked hard to find pieces that brought a modern feel to the hopeful, yet elegiac tone of the 1945 program. Instead of performing popular Jewish folk songs, the orchestra performed arrangements of poems by Aharan Harlap and Yaakov Barzilai, two Holocaust survivors. Singing in Hebrew, the soloist Hila Baggio brought some in the audience to tears as she conveyed the poets’ haunting depictions of the camps.

For many in the church, the real draw was the legendary violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter. She proposed playing Mozart’s Violin Concerto No. 5 in A-Major as an expression of “beauty that nearly hurts,” Doris Popischil, the concert organizer, says. At Mutter’s request, the program was not broadcast, in order to preserve its intimacy. Just as in 1945, this year’s concert represented a collective pledge for a better future—“a promise that this will, under our watch, never happen again,” Mutter said after the concert.

For the encore, monks joined the orchestra onstage. Their voices united with Baggio’s in Avinu malkeinu, the Hebrew prayer of repentance that Jews in the audience had likely heard days earlier during Yom Kippur.

Church bells sounded as the song drew to a close. The audience sat in silence, contemplating how horrendous acts of inhumanity had created such beauty. Again, I thought of my grandfather’s 1945 speech.

“We unlearned to laugh; we cannot cry anymore; we do not understand our freedom: probably because we are still among our dead comrades! Let us rise and stand in silence to commemorate our dead!”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook