Why Genetics Researchers Are Looking for the Loch Ness Monster

“I don’t believe that there’s a monster, but if I’m wrong, well, that’s OK.”

The Loch Ness Monster is maybe the greatest and certainly the most sturdy cryptid myth of the modern age. But after a century or so of searching, no one has been able to find irrefutable evidence of any strange creatures lurking in the murky depths of Scotland’s Loch Ness. So why would a team of serious genetic scientists decide to head back to the loch in search of the legend?

Ask Neil Gemmell, whose Super Natural History Project will do just that early next month. Gemmell, a genetics expert from the University of Otago in New Zealand, says he sees the Loch Ness Monster myth as a great way to bring attention to the study of environmental DNA (eDNA) research. “It’s a project that’s bringing people together, and it’s created more of a buzz about eDNA than probably any other project I’ve been involved in,” he says.

Environmental DNA is trace DNA that is collected from a particular environment, and then compared to available databases of genetic information to identify the various forms of life recently present in an area. Researchers working with eDNA isolate the biological scraps left over in an environmental sample (think skin cells, waste, or other biomaterial), and try to match their DNA sequence to a known creature, proving that it was there.

The technique has proven effective at finding hard-to-locate creatures such as the Alabama sturgeon. But it took a little more than science to convince Gemmell to head to Loch Ness, ostensibly in search of a monster. “My kids think this is the coolest idea that dad’s ever had, and all their their school chums thought it was a great idea too,” he says. “Spurred on by that enthusiasm, I think I’d stumbled on a way to talk about the science that I care about in a way that captures people’s imaginations.”

We spoke to Gemmell just a day before he set out for Scotland, where he and his team are set to spend the next two weeks or so collecting taking samples from the loch. “We’re going to be sampling and filtering an awful lot of water. It’s not overly glamorous to be fair,” he says. The team will be taking around 300 different water samples from different parts of the loch in order to get as wide a range of environmental data as possible. This means skimming water off of the surface in some places, and in others collecting samples from hundreds of feet down. “I don’t know quite what’s down there, but we’ll probably pick up some bacterial species,” says Gemmell. “Because it’s deep, it’s dark, and it very quickly goes from a light-driven ecology to something that’s driven by bacteria. What we find down there might be quite interesting.”

Gemmell expects that from the samples his team will be able to establish a survey of the common types of life in the loch, including bacterial life, specific plant life, and species of fish known to inhabit the waters including salmon, char, trout, and others. It’s also hoped that they might find evidence of rarer types of fish thought to inhabit the lake, such as flounder.

It’s obviously unlikely that they’ll find evidence of the Loch Ness Monster, but that doesn’t mean their study won’t shine some light on the truth of the myth. “I think the chances that we’ll find a monster are extremely small,” says Gemmell. “Of course there’s also this idea that some of the monster myth may be underpinned by giant fish that were introduced to Loch Ness or have been there. Things like sturgeon, catfish, or sharks may all be explanations of what people have seen from time to time.”

No matter what the team finds, true believers in the legend should take heart—the results of eDNA analysis are limited to the time and place they were collected. “It’s only telling us about what’s present in Loch Ness in June 2018, and probably a few days before we arrive. It’s not a history of the entire loch,” says Gemmell. This point is relevant to the many Loch Ness Monster believers who contend that the monster periodically leaves the loch to go out to sea. “If that’s true, and Nessie’s on holiday, then we aren’t going to pick up anything.”

Just for the sake of argument, what if they did find evidence of a monster?

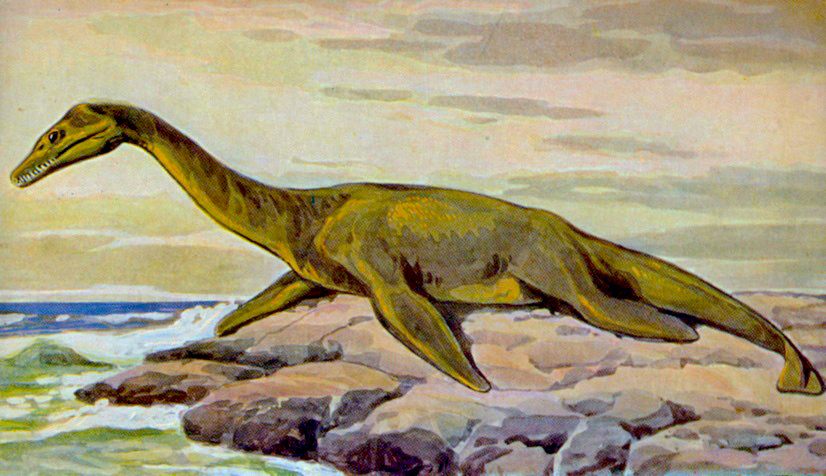

First they would have to identify it as monster DNA. “If the sequence is totally new to science, it should stand out,” says Gemmell. It has been posited that the Loch Ness Monster is alien or supernatural in origin, in which case no one knows what traces of it would look like. But the most common version of the Loch Ness legend is that the monster is a plesiosaur that has somehow survived into the modern age. If that’s the case, the Super Natural History Project is ready. “We’re starting from the position that it is a biological entity, and that there will be a DNA signature that will fit somewhere on the Tree of Life,” says Gemmell. “While we haven’t got plesiosaur DNA, we can pretty much make a good guess of what plesiosaur DNA would look like, using a process called ancestral state reconstruction.”

Essentially, if the team found DNA that they couldn’t match with available databases, they would begin checking to see if it fit in anywhere close to where they speculate a plesiosaur’s DNA might have fallen—somewhere near crocodilians and birds.

Still, if the team did find anomalous DNA, don’t expect them to rush to announce the monster’s existence to the world. Gemmell is not interested in becoming another in a long line of Loch Ness hunters who too quickly announced their findings, only to have them swiftly fall apart under scrutiny. “Ultimately you want your results to be reproducible by a separate study, one that we have no role in,” he says. “An extraordinary claim, like for example, that the Loch Ness Monster is real, needs extraordinary evidence.”

Chances aren’t good that the Super Natural History Project will finally prove the existence of the Loch Ness Monster, but the popularity of the legend is set to produce some great scientific data. “This is why we search, this is why we investigate. We don’t fully understand our natural world, and when we do these investigations, it throws up surprises,” says Gemmell. “I don’t believe that there’s a monster, but if I’m wrong, well, that’s OK. I’d suddenly write my Wikipedia page. It wouldn’t be quite what I expected it to be.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook