An Entire Continent Went Missing—But Scientists Have Found It Again

Fear not, these geologists are good at their jobs.

A continent the width of the U.S. has been missing for 155 million years. Scientists have long puzzled whether this chunk of northwest Australia has been either floating somewhere unseen, resting on the ocean floor, or slowly fusing to the underbelly of a larger landmass. Modern mapping largely ruled out the first two theories, but let’s say a 3,000-mile slab of terra firma did get lodged beneath another continent. Experts believe they would have at least been able to find some trace of it. Really, how could something so large just completely vanish?

Furthermore, if we can just lose a massive piece of land like that, that could mean scientists have been completely wrong about Pangea and our understanding of the Earth’s geological history in general.

Finally, after seven years of searching, Dutch researchers at Utrecht University have definitively located pieces of the landmass within the vast jungles of Southeast Asia.

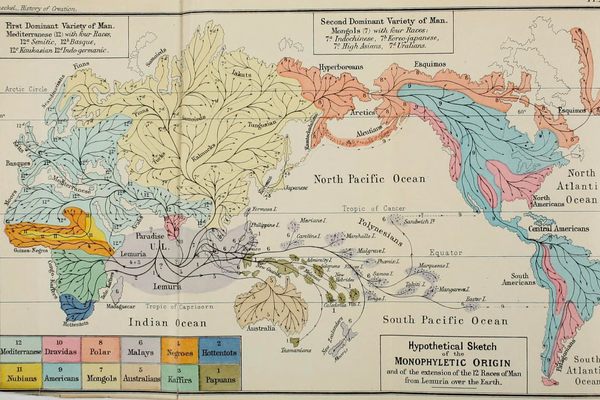

Look at a map of the world: If you “close all the oceans we know have formed in the last 200 million years, then basically the continents fit together in a C-shaped configuration,” said Dr. Eldert L. Advokaat, Argoland researcher and lead author of the study. That’s Pangea. “The interesting part is what happens in that C shape,” he said, “in the Tethys Ocean.”

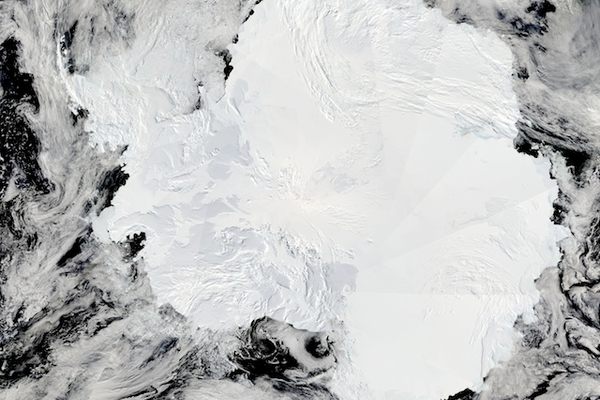

This prehistoric body of water is where Argoland disappeared during the Late Jurassic period, leaving a bite out of Australia that we now call the Argo Abyssal Plain. Geologists were pretty sure the land didn’t sink, as the “hidden” continent of Zealandia did after breaking away from Australia 80 million years ago. Rather, they worried Argoland was lost by subduction, a phenomenon in which the edge of one tectonic plate slides beneath another and gets recycled into the Earth’s mantle.

Typically, experts can trace continental subduction by offscraping, where part of the upper crust gets scraped and builds up, resulting in mountains. Such is the case with the Indian subcontinent colliding with Asia, forming the Himalayas. In the case of Greater Adria, another previously lost continent that tore away from North Africa 240 million years ago, the lower crust subducted, but offscraped remnants of the upper crust were later found all over the Mediterranean.

Further complicating the search, pieces thought to be from Argoland kept cropping up all over Myanmar and Indonesia, but samples showed they predated the continent’s split from Australia by tens of millions of years. If Argoland subducted without a trace, then the fragments found in Southeast Asia could have been from another landmass we didn’t even know was missing. If one U.S.-sized continent could disappear, how many others have done the same? Advokaat said we would “basically have no clue what happened in the Tethys Ocean.”

But thanks to his near-decade of research, along with his colleague Dr. Douwe J.J. van Hinsbergen’s, we do know what happened to Argoland: It broke into an archipelago—an Argopelago, rather—before pulling away from Australia. Its seaside slowly thinned into ribbons of continents (i.e., microcontinents), forming smaller ocean basins made of thinner-yet-denser oceanic crust. Then, they tore away and drifted for a bit before embedding themselves in various Southeast Asian jungles, where they are today. An animation published with the study shows the journey over many megayears.

The finding aligns with our present-day picture of Pangea. “We get more understanding of how the Earth works,” said Dr. Nick Mortimer, who led the research project uncovering Zealandia. “On the one hand, how and why continents break up into large and small pieces (Argoland leaving Australia). And on the other hand, how continents grow (Argoland pieces arriving in Eurasia).” This glimpse into prehistory unlocks paths of discovery for biodiversity and climate.

Of the oceans that formed since the breakup of Pangea, the Indian and Atlantic, co-author Dr. Douwe van Hinsbergen said Argoland was the last missing piece of the puzzle. But the older Pacific Ocean could absolutely harbor some missing territories, possibly tucked away somewhere in the mountain belts of Alaska and British Columbia, where van Hinsbergen said he’ll start digging for more lost continents next.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook