A California Type Foundry Is Keeping Vintage Printing Alive

“It’s a really neat feeling to help people be able to print from hot metal.”

In an innocuous building in San Francisco’s Presidio, the Grabhorn’s Institute’s Brian Ferrett boils lead and casts metal type using techniques and equipment a century old. Ferrett, is one of perhaps 100 people worldwide who cast type. At 44, he’s unusually young. Most type-casters are decades older.

To make individual pieces of type, Ferrett fires up a caster, a fancy bit of mechanical gear with a motor, cams, and levers. He lights a gas burner to melt a pot of lead, antimony, and tin; a hood over each caster exhausts the gas and metal fumes. The recipe for this alloy dates back to the 1400s, and it’s formulated to quickly cool and harden.

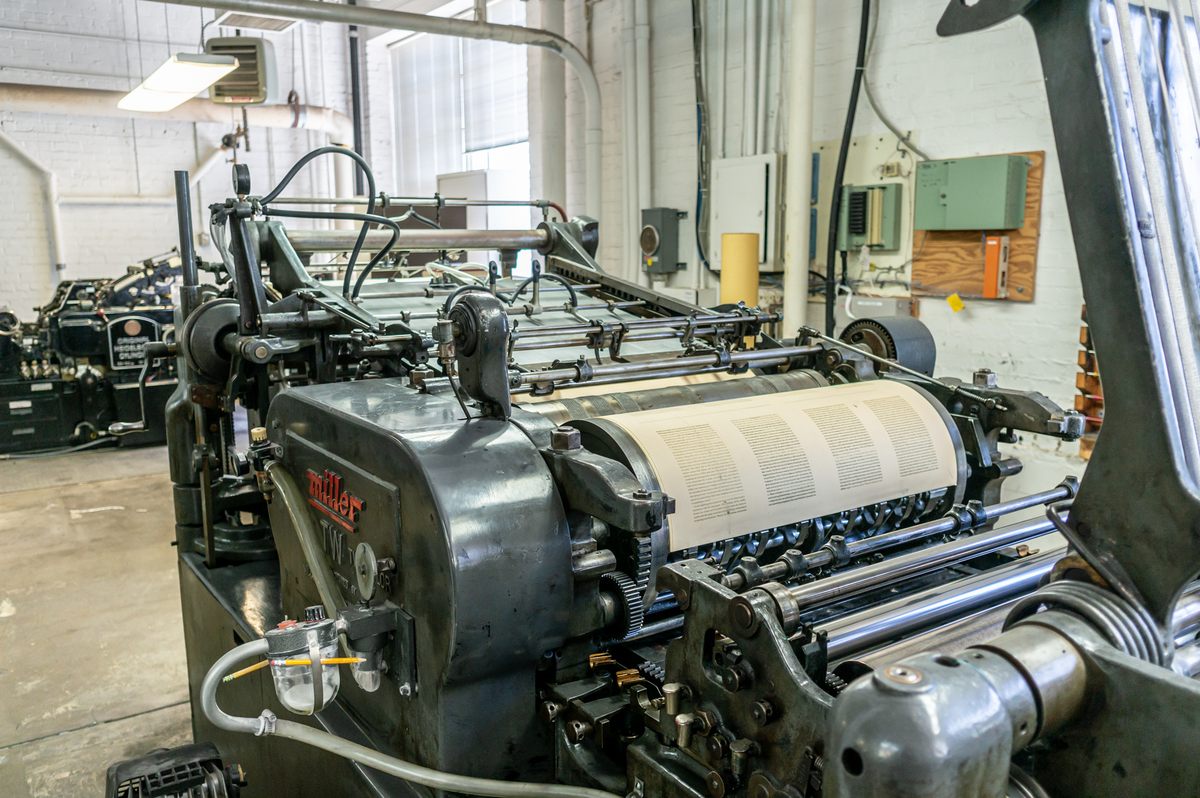

The type is sold by the pound to letterpress printers. With letterpress printing, letters and images stand in relief, allowing their surfaces to be lightly coated in ink on a press, and then squeezed with carefully calibrated pressure against paper. That “impression” transfers the ink to make a printed page or poster.

More crucially, the type Ferrett casts is used to print limited-edition books in the Grabhorn Institute’s adjacent pressroom on letterpress equipment of a similar vintage. Sold for hundreds to thousands of dollars each, these books form the largest part of the institute’s revenue and sustain it for the future.

Although digital typesetting and offset lithography have largely rendered type casting obsolete, letterpress printing and type founding remains alive at Grabhorn. The institute conducts weekly tours of operations and has regular events in its gallery, which is open daily.

Rows of machines line both long walls of the foundry. Operations are managed by Ferrett, an 11-year veteran, and his colleague Chris Godek, at Grabhorn for eight. Both were trained by Lewis Mitchell, who worked for the foundry from 1950 across multiple locations in San Francisco and several owners through 2014.

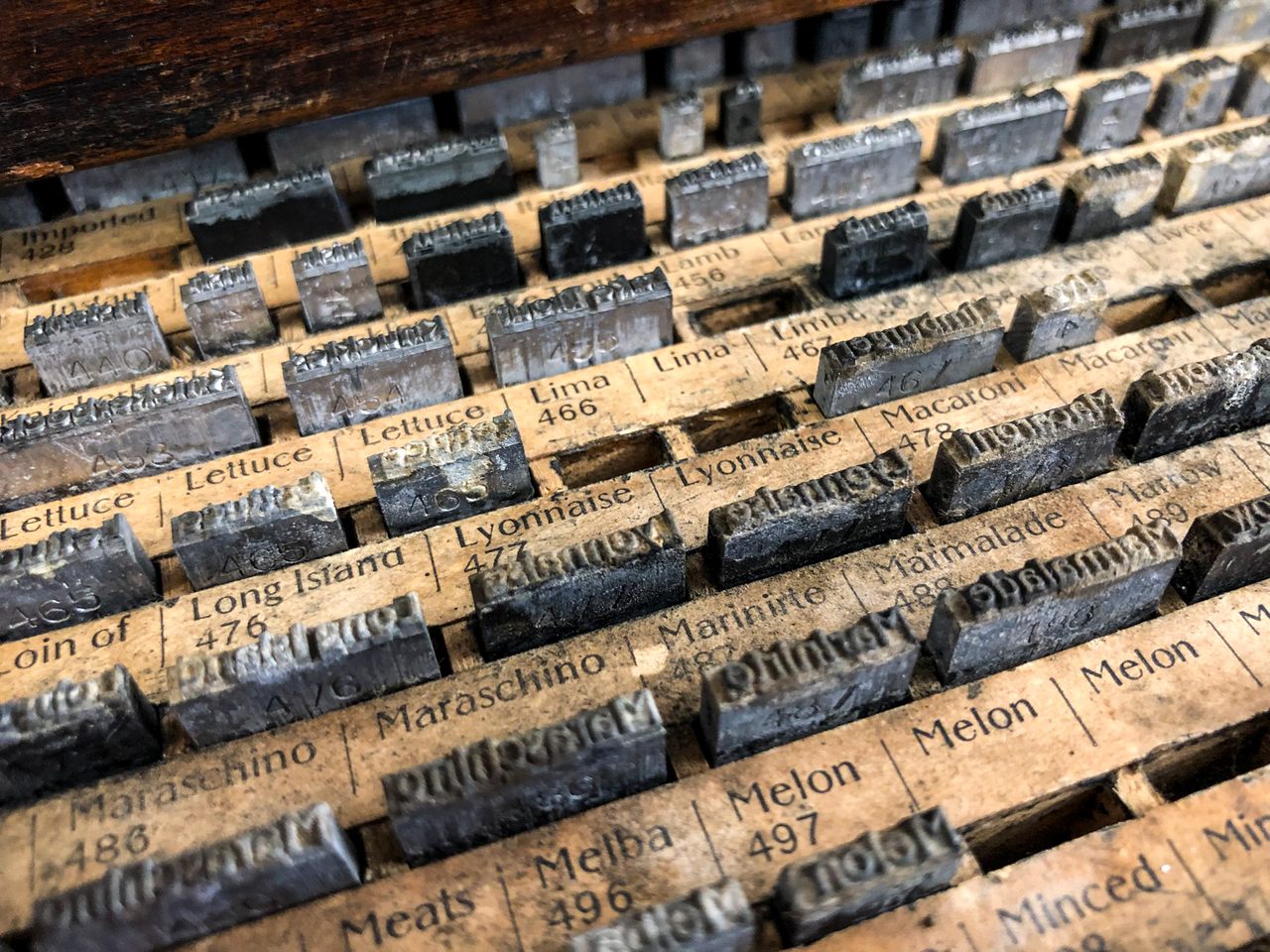

Ferrett can select a type mold (a “matrix”) from one of an estimated hundreds of thousands in the foundry. Each letter in every size and style of a typeface requires its own matrix. They’re precious, both because their tarnished brass or gleaming nickel-plating is beautiful, and because they’re scarce: The last were made decades ago and some date back far longer.

Locking the matrix into place in a Thompson caster, Ferrett can trigger it to produce a rapid, automatic, and endless sequence of the same letter. The caster squirts hot lead under pressure into a form, ejects it, smooths and shapes its five flat sides, and spits it out, repeating over and over. Ferrett credits his mentor Mitchell’s long tenure for these machines remaining operable. “He is the only reason these things work,” Ferrett says. A certificate on the wall of the foundry celebrating Mitchell’s half-century of work remains in place, updated with pencil marks and sticky notes each anniversary through his 64th.

A metal type foundry isn’t where Ferrett thought he’d wind up. He and his wife had moved to the city 11 years ago for a job she’d taken. “I literally just happened to find it in a book on relocating to San Francisco—50 things to see when you first move, and I walked in,” Ferrett says.

He had trained and worked as a printer, but in offset lithography, the technology that largely replaced letterpress. “Litho” uses thin metal plates that take ink selectively. It’s efficient, but unromantic and fairly sterile.

Ferrett started with an apprenticeship and quickly realized that “I would be able to continue making these things that nobody was doing anymore.” He seized the opportunity, and now trains the next generation.

The type-casting profession went largely extinct in the 1980s after decades of slow decline. Yet visiting the Grabhorn Institute, which operates the type foundry and a fine-edition book publisher, printer, and bindery, you’d be hard pressed to realize you were stepping backwards in time.

In the day-lit pressroom, rows of type cabinets on one side hold hundreds of drawers of type, which is set a letter at a time by hand. On the other side, an array of presses can produce anything from quick small prints for proofreading text up to large sheets that hold several unfolded pages of a book.

The institute preserves this last generation of letterpress, in which intensely manual work sits alongside some of the best industrial machines ever made. Johann Gutenberg made this method practical in 1450, and nearly every book, every magazine, every flyer, every bit of the printed word relied on letterpress through the 1950s.

Letterpress has a unique charm: It’s tactile, visible, and weighty. Try to casually pick up a tray holding a column of type ready for press, and realize it weighs 10, 20, 30 pounds. Look at it, and you can read the letters, mirrored for printing. Rub your fingers over the top, and feel what will press into paper.

It can also be immediate and rewarding. Large type and images can be locked down on a flat proofing press, inked up, and posters pulled off nearly as fast as you can imagine them, but with the visceral pop of a protest song. At some marches, such as the 2017 Women’s March event in Seattle, letterpress prints are held alongside posters made with markers and paint.

By the 1980s, nearly all letterpress gear was abandoned for efficiency’s sake as offset printing took over. But craftspeople and universities kept the tradition alive with art prints, small editions of books, wedding invitations, and posters.

Those keeping letterpress going include Andrew Hoyem, who founded the Arion Press in San Francisco in the early 1970s. It owed its roots (and gear) to the two Grabhorn brothers, who began publishing in the city in 1919.

In 1989, after multiple moves and owners, Hoyem acquired the faltering foundry, Mackenzie & Harris, which began life in the city in 1915. He sustained it—as M&H Type—to feed his publishing needs and to sell type to remaining letterpress printers during the dark days when type and equipment were being melted down, burned, or thrown in dumps.

A drop in demand and rising real estate costs led Hoyem and others to start the nonprofit Grabhorn Institute in 2001. Hoyem retired in 2018 after nearly 60 years as a printer and publisher.

Grabhorn survives on the symbiosis between its foundry and press. The Arion Press produces a few titles a year. Its most recent was an illustrated Frankenstein, printed in a run of 220—its 115th title. The standard edition cost $1,200, while a deluxe version in a laser-engraved wooden box ran $2,500—and sold out.

On a recent visit, Frankenstein was in the bindery. Bindery apprentice Samantha Companatico used a book press with a heavy weight to compress a copy of the book’s pages and paint on binding glue. Nearby, lead bookbinder Megan Gibes glued a set of pages into the title’s covers. (Gibes is a former apprentice, and all the staff apprenticed at Grabhorn.)

For the kind of limited-edition books produced by Arion Press, bookbinding operations remain intensely manual to preserve quality and add fancy, time-consuming details, like fine foil stamping and—for the deluxe Frankenstein—a hand-sewn binding. (Keeping with a bookselling tradition dating back centuries at least, the press also offers a few sets of unbound printings for someone who wants to hire their own bookbinder.)

But these books wouldn’t be feasible if the many pages of text were set by hand, a character at a time. Instead, the foundry also keeps several Monotype type-composition systems running. Monotype was introduced in 1900, and favored for book work. It splits keyboarding and casting, almost like computer and printer. An operator types on the keyboard, which punches corresponding holes in a roll of paper tape, nearly as a song is punched into a player-piano roll. To reproduce the typing as lines of type, the tape is “played back” into the caster, which uses pneumatics and motors to pick the right type mold from a set of 225 and cast each letter.

Grabhorn bypasses the keyboards, though, which are more temperamental from wear than type-casting machines. The typesetters use an even more efficient method that looks like—well, a Frankenstein’s monster of circuit boards and pneumatic tubing. The CompCAT, designed by Bill Welliver and used worldwide, allows composition and text previewing on a Mac, and then fools a caster into thinking it’s reading paper tape to “output” type. It’s a neat bridge of old and new.

Regardless of the particular system involved, Grabhorn is a much-loved institution for those who love to talk type. “Anywhere I go that there’s a press, people are excited that we’re here,” says Ferrett. “It’s a really neat feeling to help people be able to print from hot metal.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook