How One Woman Transforms Plants Into Pigment

Kazumi Tanaka paints the natural world with the essence of flowers.

It’s the patch of goldenrod that pulls us to the ground first. “I want to collect some of this,” Kazumi Tanaka says, crafting scissors in hand.

Tanaka is gathering richly colored flora native to Manitoga, a 75-acre woodland estate in Garrison, New York, for her most recent artistic pursuit: creating natural watercolor inks from plant specimens. Tanaka is Manitoga’s fifth and current artist-in-residence, and her project INK: The Color of Manitoga illustrates the scientific process behind her art making. Once the natural materials are chemically transformed into watercolors, the multidisciplinary artist paints botanical drawings with the ink derived from the plant specimens.

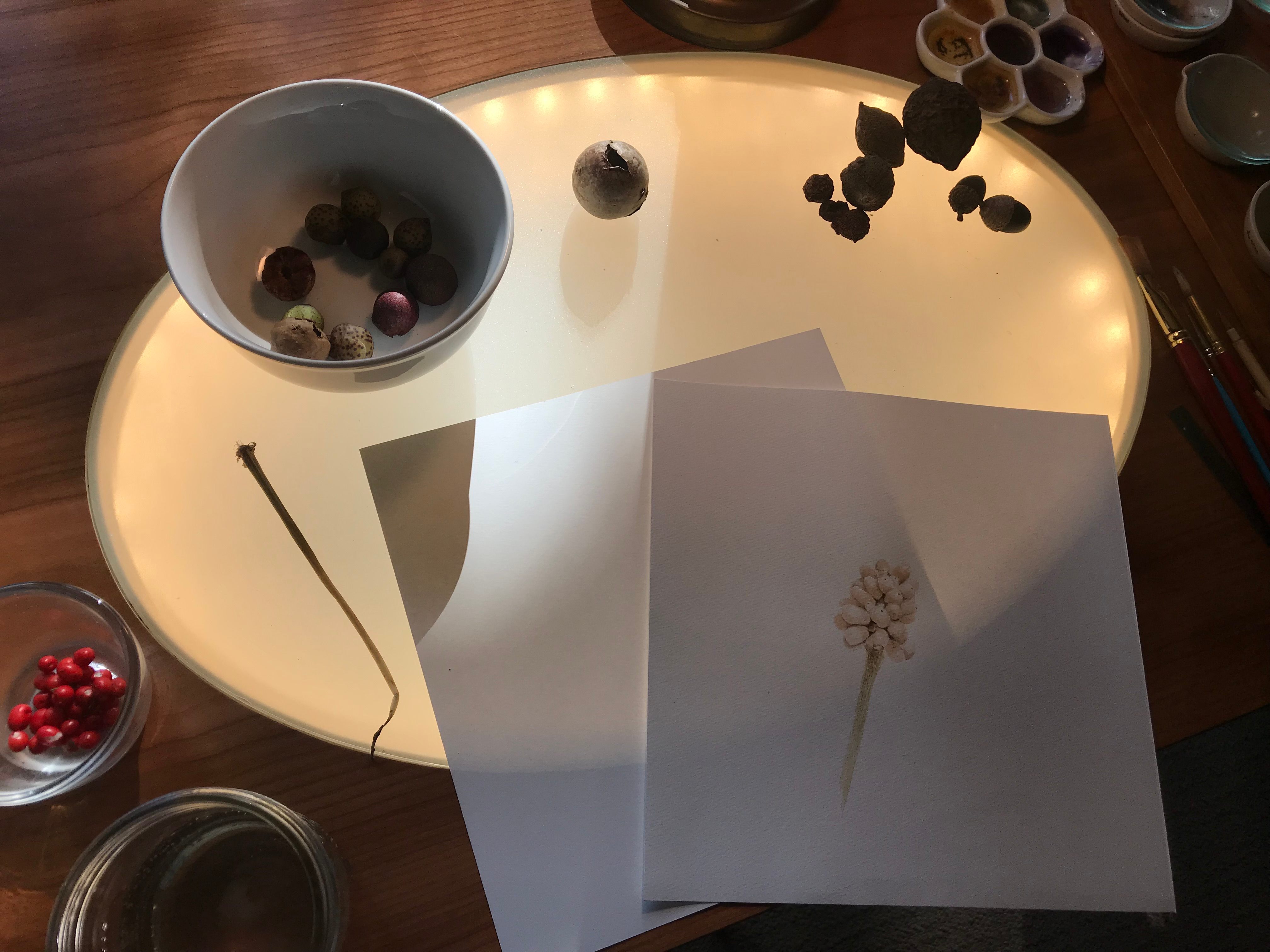

The artist residency at Manitoga is a year long, so Tanaka began her search for naturally occuring hues in January 2018. “I came across the mountain laurel because it was red and green which I didn’t expect to see in the middle of winter,” Tanaka says. “And I managed to make three different colors out of that specimen.” Using a lab set-up she built herself (Tanaka is also a woodworker and antique furniture restorer), she crushes the specimens she’s collected until leaves become liquid, and petals become pigment. Left with a concentrated amount of vivid plant paste, Tanaka uses a high-school chemistry set to distill water from Manitoga’s Quarry Pool and mixes it in with the “paint,” along with gum arabic for preservation purposes. There are other bodies of water on the estate that Tanaka considered drawing water out of, like the silent and reflective “Lost Pond.” But based on her observations, the pond’s water had too much algae in it to be usable because, as Tanaka says, “it’s a still water, whereas the Quarry Pool is constantly moving.”

Following a half-hour process of letting all the ingredients settle, a natural ink emerges like a new crop bursting from the soil. The final step in this plant-to-paint transformation happens now. “As long as I transfer [the ink] to the paper right away, it remains quite a fresh color,” Tanaka says. Once the inks are ready for use, the artist creates a series of botanical drawings and paints each one with ink derived from the plant depicted. Think of a sustainable version of color-by-number, except Tanaka colors by species.

Tanaka’s environmentally conscious art is rooted in her upbringing and culture. “I was thinking about how my parents used to go fishing and they used to just eat what they caught,” she says. “And how they used to say ‘it just tastes different.’ It’s a similar concept.” Though Tanaka celebrates the wide color spectrum of manufactured watercolor paints available in art stores, her interest in making her own comes from an innate curiosity about the world. “[I love] giving a challenge to myself and thinking, ‘What can I create?’ Everything in this room I made from out there!” she says, gesturing toward the wall-sized window that encloses her lab. “It just makes it worthwhile to do this effort.”

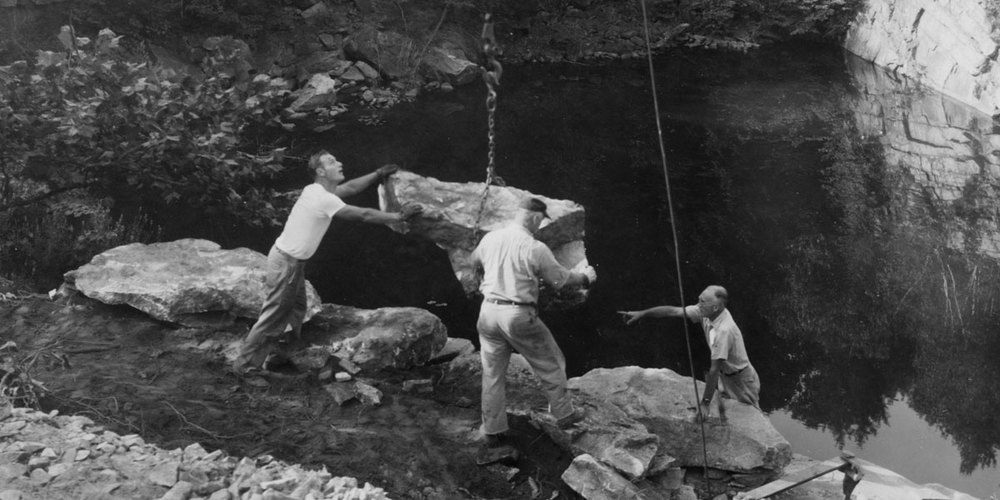

The grounds of Manitoga began as a rock quarry, purchased in 1942 by American industrial designer Russel Wright and his wife, Mary. The curation of the landscape started immediately, while construction of the buildings formally began in 1958; over the next three years the designer incorporated his heralded, revolutionary concept of easy, informal living into his development of the property. Found stones were rearranged theatrically, creating a natural amphitheater around the glass-walled house and design studio Wright built above Manitoga’s man-made swimming pond. In the creation of this Hudson Valley escape, no element was altered or spared—only moved. Gardens decorate the roof, an example of design’s conscious pivot toward sustainable “organic architecture” at the turn of the 20th-century, and a subtle advertisement for Wright’s appreciation for hue. “The original idea for The Color of Manitoga came from Russel’s obsession with color,” Tanaka says. “He had a whole line of glazes for his pottery that are very specific.” Wright’s ceramic dinnerware line, marked by his trademarked signature on each individual piece, was the project that effectively made him a household name.

Tanaka was born in Osaka, Japan, and her heritage is reflected in the clean lines and emphasis on curating the natural world seen in Wright’s home and studio at Manitoga. The designer was heavily influenced by his visits to Southeast Asia, and Manitoga serves as evidence of this. “Japanese gardens are very controlled [and carefully placed],” Tanaka says. The artist, careful to not situate Wright as an architectural mimic, adds: “But I also really admire his taste: he brought the feeling of [Japan] without copying anything. He brought his own sensitivity and love of those different cultures.” A subtle yet considered repurposing of nature into art is what unifies Wright’s and Tanaka’s visions for their projects—which both exist firmly in the embrace of their environment. “The program here and this project connects me to both Japanese and American history,” Tanaka says. “It’s a great marriage that I was given this opportunity. It makes sense.”

In the lab, Tanaka points to a nearly pitch-black saucer of liquid, recently mixed. “The oak gall ink is very exciting to me right now,” she says. “The more iron I add and the longer I cook it, the more black it becomes.” Iron? Natural, yes, but I ask her to explain. When acorns are cooked they turn from brown to black, but what helps deepen that color is rust, Tanaka tells me. To achieve the darkest possible shade, the artist buries a rusty nail underneath the liquid, and lets it sit. “Tannic acid reacts to the vinegar and rust and turns it black,” she says. “That’s why it’s called iron gall ink, too.”

Found in the nutgalls of an oak tree’s branches, tannic acid has historically been used as a medicine, to pen the Declaration of Independence, and as a culinary assist. “I remember when my mother used to cook New Year celebratory food, one of [the dishes] was black beans, and I saw her pull out a nail!” Tanaka says. “She’d say, ‘This is what we do to make the beans blacker.’”

The setting sun begins to cast a different light on each of the ink bottles, which are lined up in order of discovery. Naturally, the winter mountain laurel is first, now a faint beige. A couple of bottles down is the summer mountain laurel, which Tanaka collected in June. It’s a grey-tinted green. This seasonal contrast in colors makes the passage of time plain, and allows for a broader palette for Tanaka to paint from. Other inks include a striking purple derived from skunk cabbage in March, which Tanaka used to paint an indigo tree; when I visit in October, the tree is a softer green. Over time, the colors naturally distort the longer they are exposed to heat, like a mood ring. Tanaka doesn’t load her pigments with artificial chemicals like store-bought versions, so they adjust to their environment at will. As it turns out, the most plentiful color at Manitoga is the most difficult to preserve. “Green is very hard to keep, because its a chlorophyll and a chlorophyll is basically produced by the sun,” says Tanaka. “So when the sun is gone, it disappears.”

Though Tanaka’s project is rooted in improvisation, there is an equally important record-keeping procedure that allows the artist’s exchange with the landscape to flourish. Every time Tanaka collects a new specimen, she plots the place she finds it on a color-coded, large-scale map of Manitoga. She also logs the scientific names, dates, and times of her plant discoveries. Tanaka’s documentation of the collection, transformation, and creation of her art dovetails with Wright’s. “For him, design is not really about the product, its the process of getting there,” executive director of Manitoga Inc. Allison Cross says. “Manitoga was a process and continues to be [one].”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook