Mapmaking Taught Skiing’s ‘Rembrandt of Snow’ the Art of Patience

James Niehues has spent decades painting finicky trails.

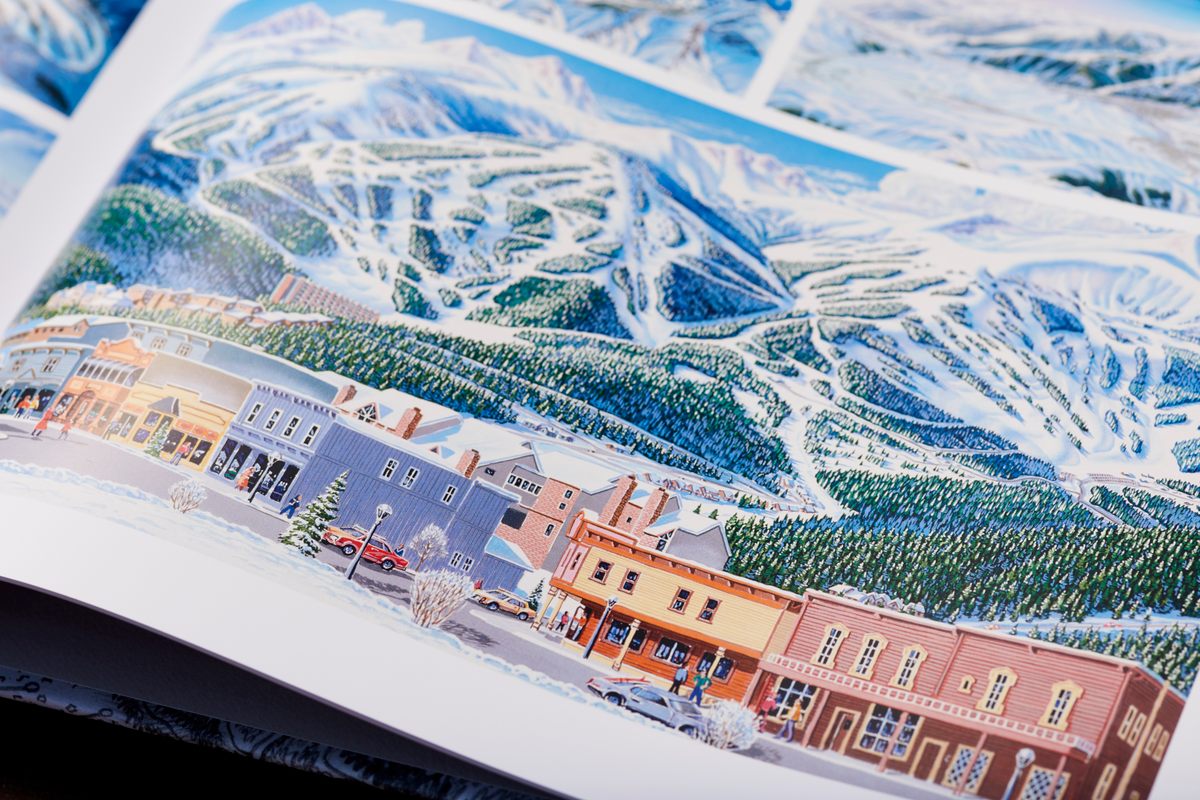

Skiers might not know James Niehues’s name, but they have probably studied his maps. Over a decades-long career, the 75-year-old has hand-painted trail maps for over 200 ski resorts across the U.S. as well as a few in farther-flung places including British Columbia, Serbia, and New Zealand.

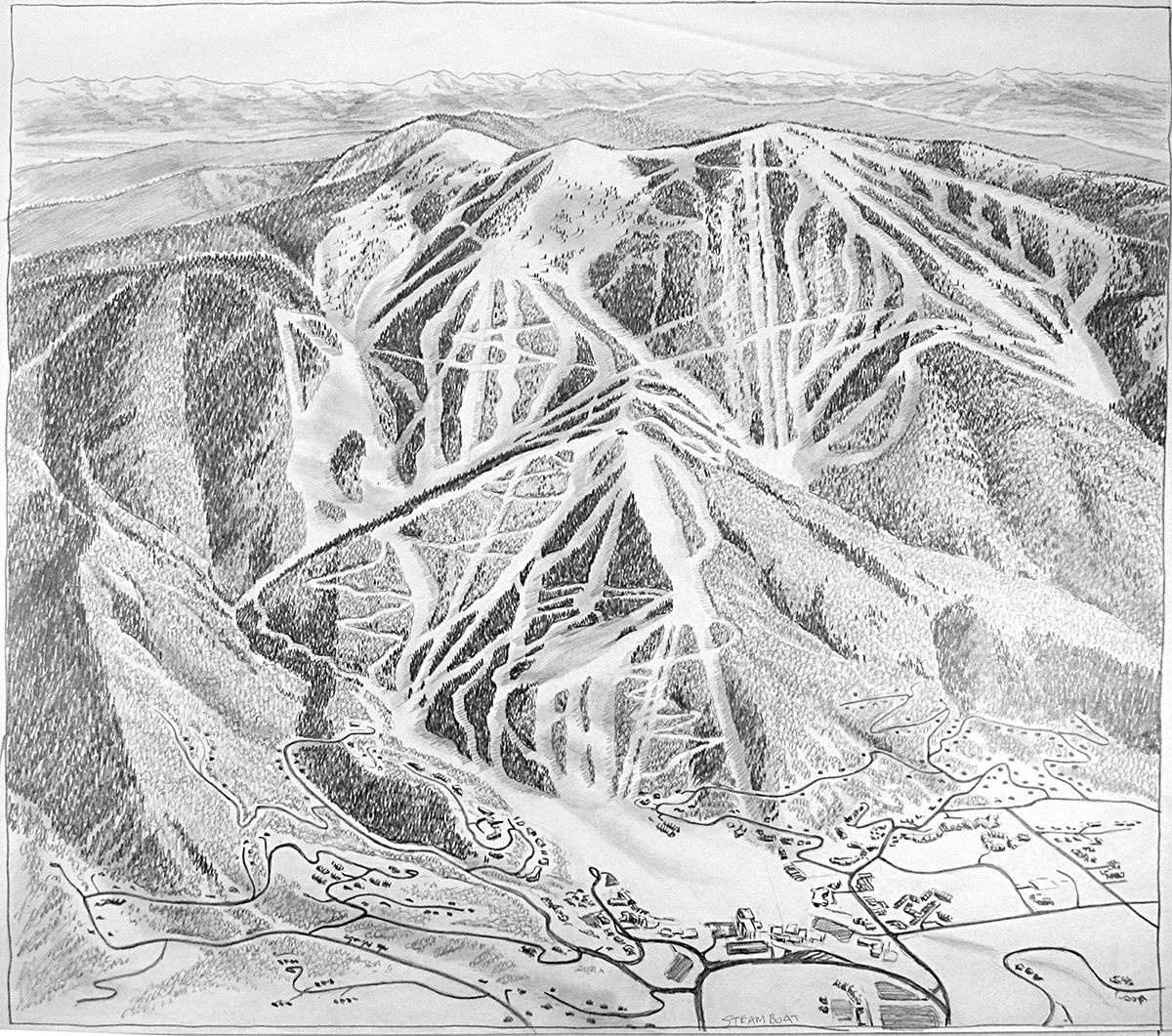

The so-called “Rembrandt of Snow” stumbled into his mapmaking career in 1987, shortly after moving with his wife and kids to Denver from Grand Junction, Colorado. Desperate for graphic design work, he connected with local artist Bill Brown, who in turn handed him a job making the trail map for the Winter Park resort. Thirty-four years later, Niehues has created enough pieces to sell a coffee table book (The Man Behind the Maps, published in 2019) and he’s still not done: This ski season, he created a new map for Mad River Glen in Vermont, and is already at work on a new collection of sketches of iconic American landscapes.

Given the fastidious nature of his work (and how prolifically he churns it out), Niehues spends a lot of time in quiet contemplation of the world around him—a state of being that might be familiar as the Covid-19 pandemic stretches on. Niehues spoke with Atlas Obscura about his technique for painting ski trails, seeing kangaroos near the slopes in Australia, and why he decided to hang up his skis for good.

What appeals to you about painting ski trail maps?

From the time I was in my teens, I was infatuated with the landscape and all the recreation it offered—at that time it was hiking, biking, fishing and hunting. Growing up in Colorado, I explored mountains, canyonlands, rivers, deserts. I have also enjoyed drawing and painting with as much detail and reality as I can. In college I was hired by Dennis Lowery, who operated a graphic design and ad agency out of his garage as a paste-up artist. One of my projects was putting together a hunting map of Western Colorado. I was hooked. But, it would be 20-plus years before I would meet Bill Brown and put a pencil and brush to a ski map.

What’s the most challenging aspect of the work?

Showing all the trails in the most understandable and navigational way. It may not always be in one view, but I strive for the single view because it leaves no doubt about any trail connections or direction. Many mountains have slopes on more than one face, which requires manipulating the features to show the back side with the front on a flat sheet of paper. This has to be done with care since skiers will be referring to the image to choose their way down; all elements have to be relative to what they are experiencing on the mountain.

How did you get into painting ski trail maps in the first place?

I moved from Grand Junction Colorado to Denver to pursue graphic design and illustration. I struggled to make ends meet for some time and I looked up Bill Brown to see if he may have an overflow of illustration work. My timing was perfect since he wanted to pursue other interests—and instead of getting a job I got a career. It fit me perfectly, except I couldn’t ski! Bill didn’t ski either, but referenced aerials for his projects. I felt it would help me interpret the experience if I skied the terrain that I illustrated. Although I never could ski any slopes above intermediate, getting on the mountain added to my ability to illustrate the slopes.

Are you skiing much these days?

I have retired my skis. Several years ago I skied with my son and grandkids and had a pretty tough time getting down the slope. I just don’t get the time away from the drawing board to be in good enough shape at my age to feel safe on the slopes.

Who inspired your style?

I admired Hal Shelton’s and Bill Brown’s technique, and I strove to replicate it. It was the most credible, accurate, and attractive representation of the slopes.

Your work has allowed you to travel the world. Which destinations stand out?

My wife Dora traveled with me to New Zealand and Australia, making those three trips especially memorable. In Australia, the parrots were a treat at Thredbo Village and on the lower slopes and you would get glimpses of kangaroos along the roads. New Zealand had such diverse terrain, but the most unsettling flight I’ve had occurred at a small resort in New Zealand. The helicopter they hired was just a bubble for two [with] what looked like a Volkswagen motor. The helicopter shook to make the altitude I needed to shoot the aerials; I felt like an ant clinging to a leaf.

Dora and I also went on a scenic flight to Milford Sound, and the flight back was below ground level at least 30 percent of the time, meaning we flew in canyons. We saw the second-highest waterfall in the world and skimmed across lakes. She was not too happy with the pilot; as much as I like flying, I had to confess I was a little on edge…but [it was] memorable. There was a time in Wyoming, while photographing Grand Targhee, that the weather was so perfect with no wind that we practically skimmed the slopes of the Grand Teton—just yards off the wing tips.

Has technology changed the way you work?

I used to use a film camera and typically shot 10 rolls to get the detail and angles I wanted for each project. The sketch was drawn at full size, since the only way to transfer the exact approved image was to blue-print the sketch, send it out snail mail for approval, then transfer by tracing the blueprint with changes onto the painting surface. This took weeks. Today the digital camera eliminates processing of film and easier review and storage. Proofs are sent by email and can be returned the next day.

Your work requires a diligent and imaginative eye. Has your process helped you cope with these long stretches of shutdowns and isolation during the pandemic?

When I first began my ski map career in 1987, painting the forest’s multitude of trees seemed overwhelming. I even cut slashes out of my brush to produce three tree trunks instead of one. But I wasn’t happy with the result and resolved to paint each trunk with a single stroke. I thought I was patient but I learned to have more patience. My projects sometimes drag out due to issues like weather. It has proved to be well worth the long hours. This patience has helped me to see that there’s a light at the end of the tunnel: It’s worth the time and effort to be safe to live and paint.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook