How Scholars Cracked a Medieval Alchemist’s Secret Code

Written in a puzzling Latin cipher, it contains his formula for eternal life.

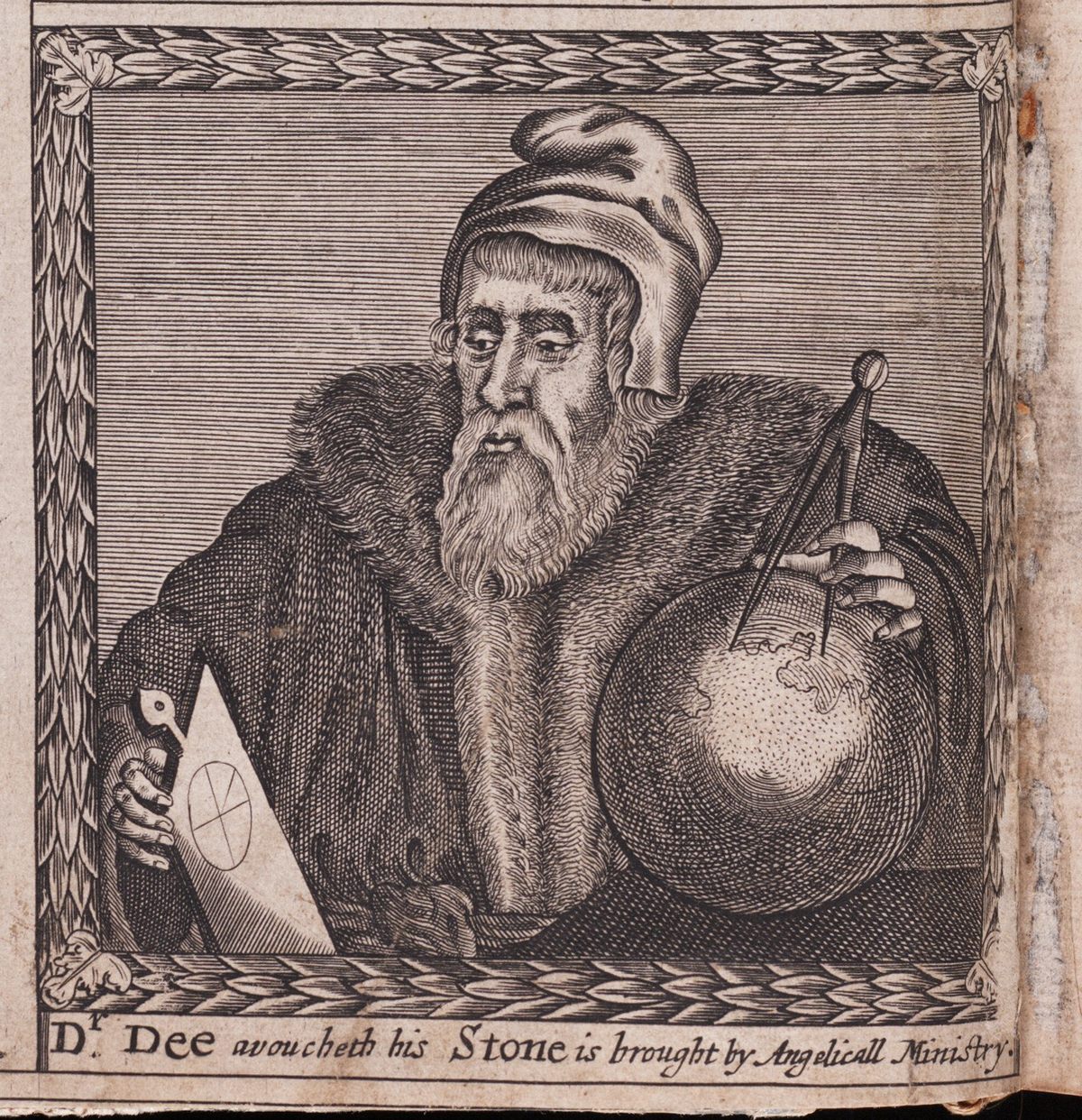

In summer 2018, Megan Piorko was deep into research for her doctoral dissertation on 16th- and 17th-century alchemist and physician Arthur Dee. On a beautiful London day, she called up a little-studied alchemical notebook from the archives of the British Library, Sloane MS 1902. Immediately, Piorko was intrigued. The notebook, to which both Dee and his famous alchemist, polymath father, John Dee, had contributed, was “odd,” she says. The fabric and leather-bound manuscript has 31 leaves of both parchment and paper. Certain pages are written upside down, so Piorko had to flip the entire notebook to read it. It was on one of those inverted pages that she found a puzzling passage written in code. On an opposing page was a strange-looking table filled with letters. She didn’t know it at the time, but the coded text had been hiding the alchemists’ recipe to the elixir of life—what those in the profession called the “Philosopher’s Stone.”

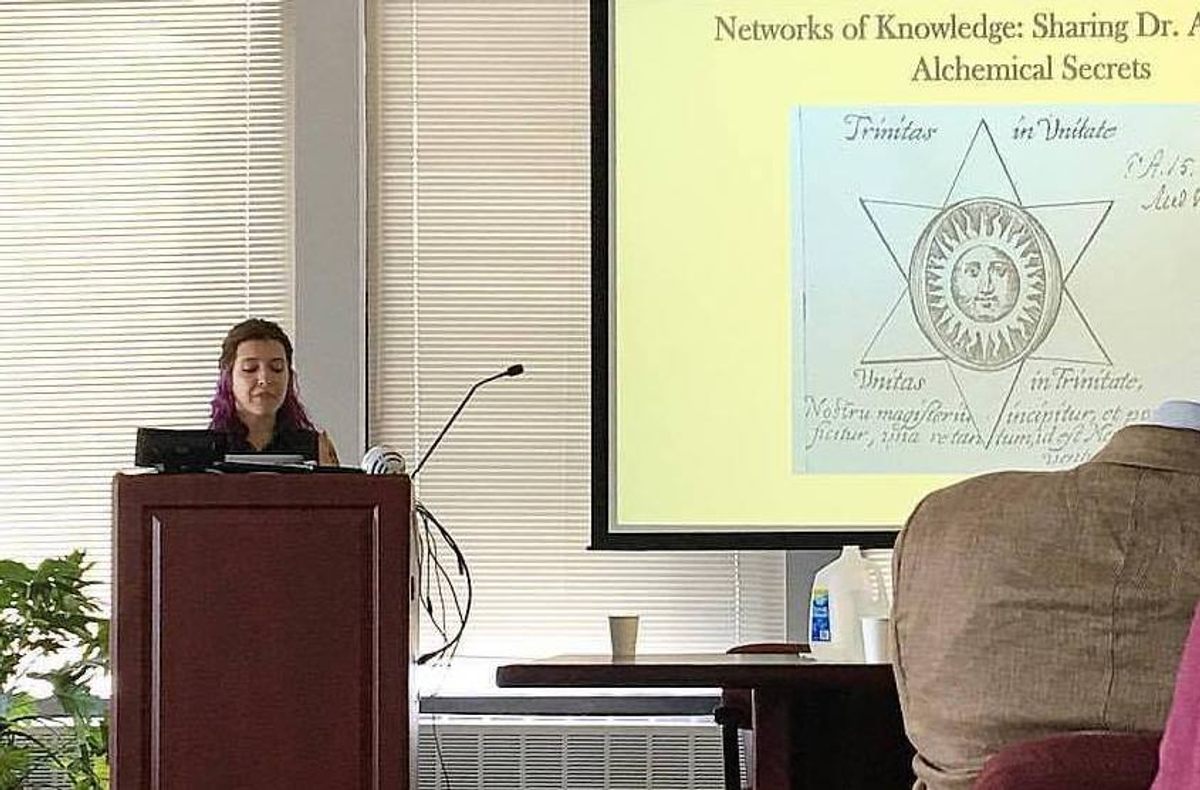

Fast forward a year and change to November 28, 2019, and Amsterdam’s 10th Annual Society for the History of Alchemy and Chemistry Post-Graduate Workshop. Piorko, who was finishing her PhD at Georgia State University, had organized the event, in a hall donated by none other than The Da Vinci Code author Dan Brown. At a post-conference happy hour in a cozy pub, Piorko and a friend, digital humanities scholar Sarah Lang from the University of Graz, found themselves discussing the peculiar notebook. “I was like, ‘Oh, it actually has this really cool cipher in it,’ and so we were just looking at it on my phone,” says Piorko.

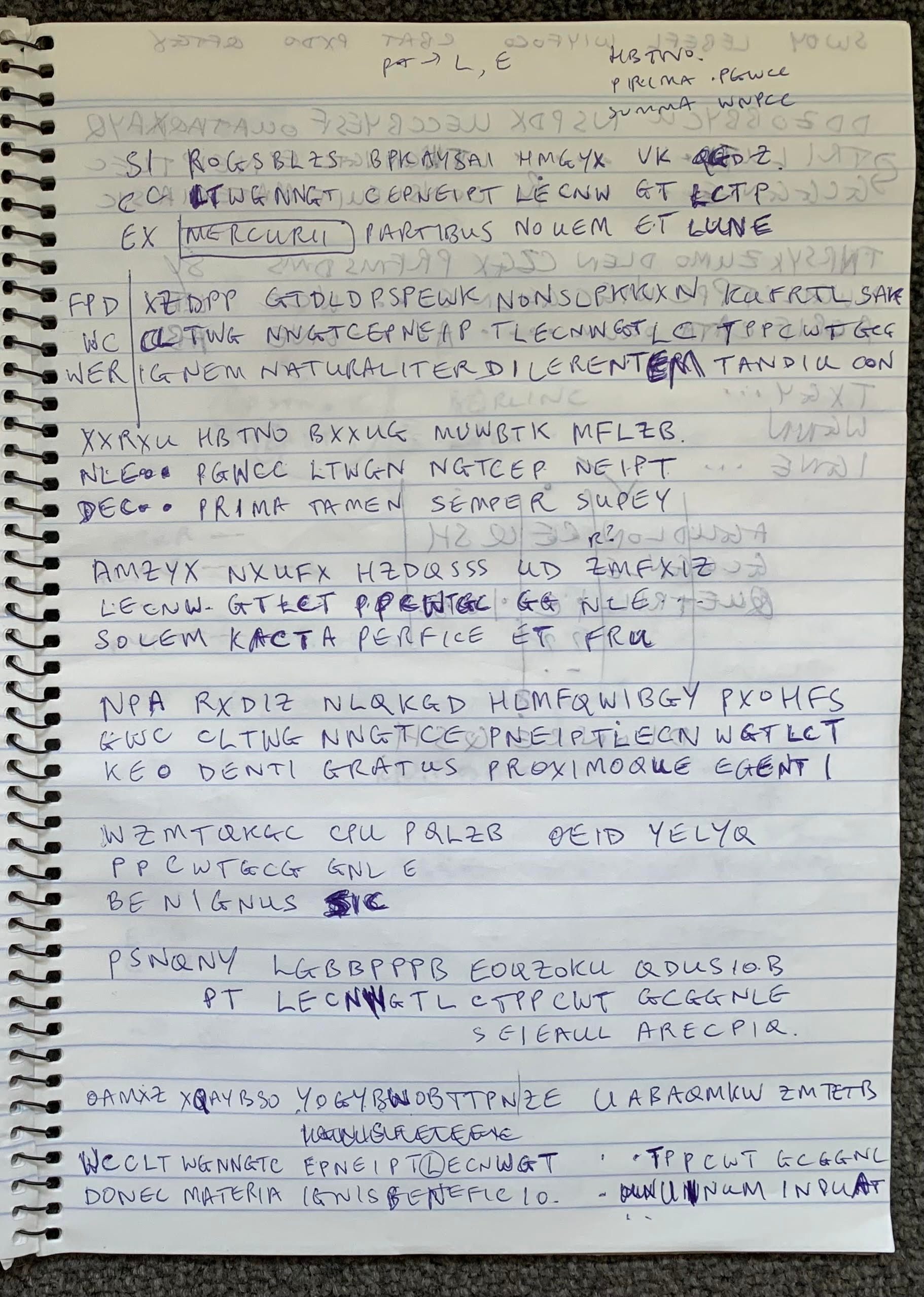

They inspected Piorko’s images of the 177-word encrypted text, which carried the title, “Hermeticae Philosophiae medulla” or “Marrow of the Hermetic Philosophy.” After the Latin title, everything else looks like gibberish: words such as “ozxkwxfg” and “qqdz” are spaced out across several pages. On the accompanying table, a two-letter heading is followed by two rows of 11 letters each.

“[Lang] tried to initially crack it on a napkin,” Piorko laughs. Though she wasn’t able to solve it, Lang did learn that the text was encrypted using a substitution cipher, where letters from the original text are swapped out for different ones. She made this conclusion based on the table, which would have required a keyword to be applied to the text. “I think it would actually be possible” to crack the cipher on a napkin, says Lang, “if it had been a cipher on the cipher level of the time, but it turned out to be a very well-encrypted cipher.” Medieval ciphers “were mostly really bad,” says Lang. But this one wasn’t like most.

Later, working together at the Science History Institute in Philadelphia, Lang and Piorko figured out that the cipher was “probably in Latin because of the Latin title and because of the letters that are missing in the table that aren’t in Latin,” says Piorko. In Latin, V and J are replaced with U and I, respectively. After some more digging, Lang says, she figured it was likely a particular kind of cipher called a Bellaso/Della Porta cipher, a polyalphabetic substitution code invented by Italian cryptologist Giovan Battista Bellaso in 1553 and used by Giambattista della Porta in 1563. Most exciting of all, a note scrawled in the margins indicated that Arthur Dee had likely written the encoded text at the same time he claimed to have discovered the recipe for the Philosopher’s Stone. Piorko guessed the encrypted text could be that very recipe. Armed with these discoveries, but no actual solution to the puzzle, it was time to call in the professional codebreakers.

Piorko and Lang published their work as part of the 2021 virtual HistoCrypt conference in September. The conference “has a very interesting audience,” says Lang. “It’s mostly computer science people interested in historical ciphers and then a few historians who basically pitch their ciphers that they can solve and then these hoards of computer scientists jump on it and try to help out.” After presenting their work, Lang and Piorko were inundated with emails from cryptologists asking for the full text of the cipher. Two well-known codebreakers tried to crack it and came up empty, and Piorko started to worry that a solution might prove elusive. That’s when she got an email from mathematician and cryptologist Richard Bean, a research fellow at the University of Queensland: “I’ve solved it!”

Bean has a knack for figuring out previously unsolvable ciphers, from a 1920s Irish Republican Army’s encoded military message to one Cambridge professor’s encrypted note from beyond the grave. A regular at HistoCrypt, Bean came across Lang and Piorko’s cipher around August 10. “I immediately started looking at it, mainly on the weekends,” he says. “And I solved it around the 29th of August. So, yeah, it took a few weekends.

“The first step is to look at the frequency of the letters,” he says. Then, assuming the cipher was a Bellaso/Della Porta, Bean needed to figure out the keyword. In a Bellaso/Della Porta cipher, the keyword—a password, of sorts, to the code—is used to determine how one should substitute letters in the encrypted text. Bean scoured the text for repeated letter patterns, indicative of repeated Latin words, to reverse engineer the keyword. He finally figured out that the keyword wasn’t a single word, but a staggering, 45-letter phrase—“sic alter Iason aurea felici portabis uellera Colcho.” Translated into English, the text, borrowed from an epic poem about Jason and the golden fleece, says, “like a new Jason, you will carry away the golden fleece from the happy Colchos.”

“It’s very exciting” when you finally solve it, says Bean. He felt like the professor from one of his favorite books he read as a teenager, Jules Verne’s A Journey to the Center of the Earth. “It was just a real cipher!” he laughs. “And it wasn’t about going to the center of the Earth through a volcano in Iceland.”

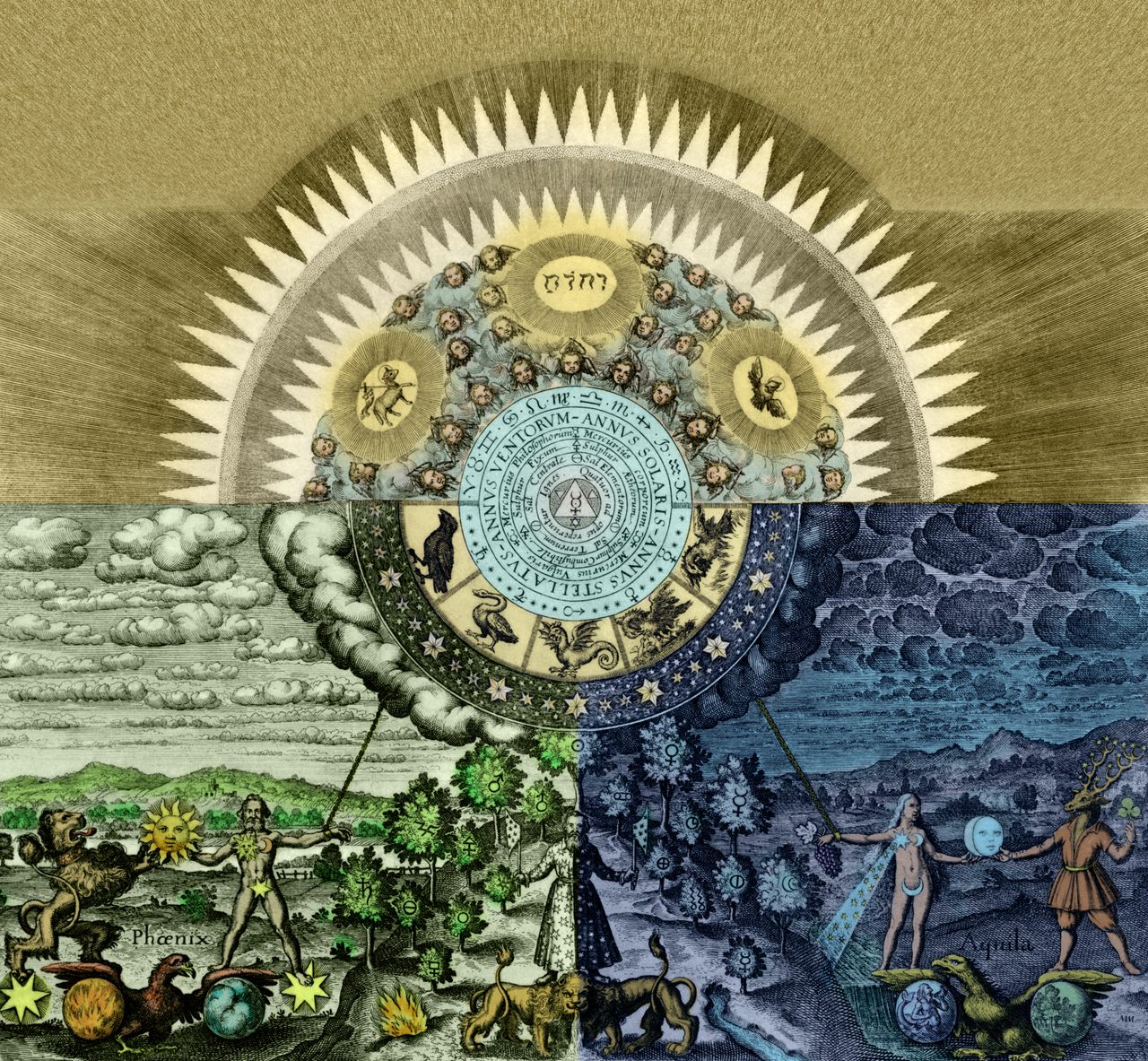

The decoded text describes the specific procedures to create the elixir of life. One step alludes to taking an alchemical “egg” from a slow-burning furnace popular with alchemists and known as an athanor. Other steps explain how long to wait for the three universal alchemical phases to occur: black, white, and red. If all the steps are followed correctly, “then you will have a truly gold-making elixir by whose benevolence all the misery of poverty is put to flight and those who suffer from any illness will be restored to health,” the text states.

The trio are currently working on their first academic journal article about the cipher and its secrets, which will include the experiment procedures and more about the man behind the cipher—Arthur Dee. His father, John, “put a lot of pressure on Arthur as his firstborn son. He named him after King Arthur. He was going to be his father’s legacy,” says Piorko. Dee “found himself to be in his dad’s shadow a lot” and was constantly trying to prove himself. Discovering the recipe to the Philosopher’s Stone was one moment when he stepped out of the elder Dee’s shadow, at least momentarily.

There are already academics eager to recreate Dee’s experiment. Piorko says once there’s “a really good transcription of the plain text in Latin and then a translation in English,” the team will be reaching out to colleagues who “work in the history of alchemy and chemistry that also have degrees in chemistry [and] recreate alchemical experiments,” to see if they can copy Dee’s recipe for eternal life.

While Piorko’s not confident that Dee’s formula will amount to anything, she still admires the “search for higher meaning” that he and other alchemists aspired to. To them, the Philosopher’s Stone was real. “Who am I to say it’s not real to them,” she says.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook