Meet the Woman Who Is Preserving the Smell of History

One scientist’s quest to capture old scents.

Cecilia Bembibre sampling the VOCs of an old book. (Photo: HMahgoub/Used with Permission)

We experience our world with five senses to guide us, but for the most part, we learn about the past with only three. We have become adept at preserving our history in audio, visual, and tactile forms, while old recipes can communicate taste, but rarely do we ever think to capture a whiff of the scents that swirl around us.

Luckily, there are scientists who think that stinks, and are doing something about it. Cecilia Bembibre, a doctoral candidate at University College London, is attempting to preserve history like very few before her. She’s cataloging the smells.

Smells “help us connect to history in a more human way,” says Bembibre, whose project combines chemistry, electronic noses, and centuries-old English manor houses.

Bembibre records the smells of historic locations and objects around England, looking for sites that are both culturally significant and strongly scented. Currently, her research is focused on two locations: Knole House, an English estate that has been inhabited by the same family since it was built in the 15th century; and the library in St. Paul’s Cathedral, a perfectly stuffy room full of books and pieces of furniture that are hundreds of years old.

The room at St. Paul’s is opened by appointment only, helping to maintain its heady scent. “It’s a wonderful library and it smells great,” says Bembibre.

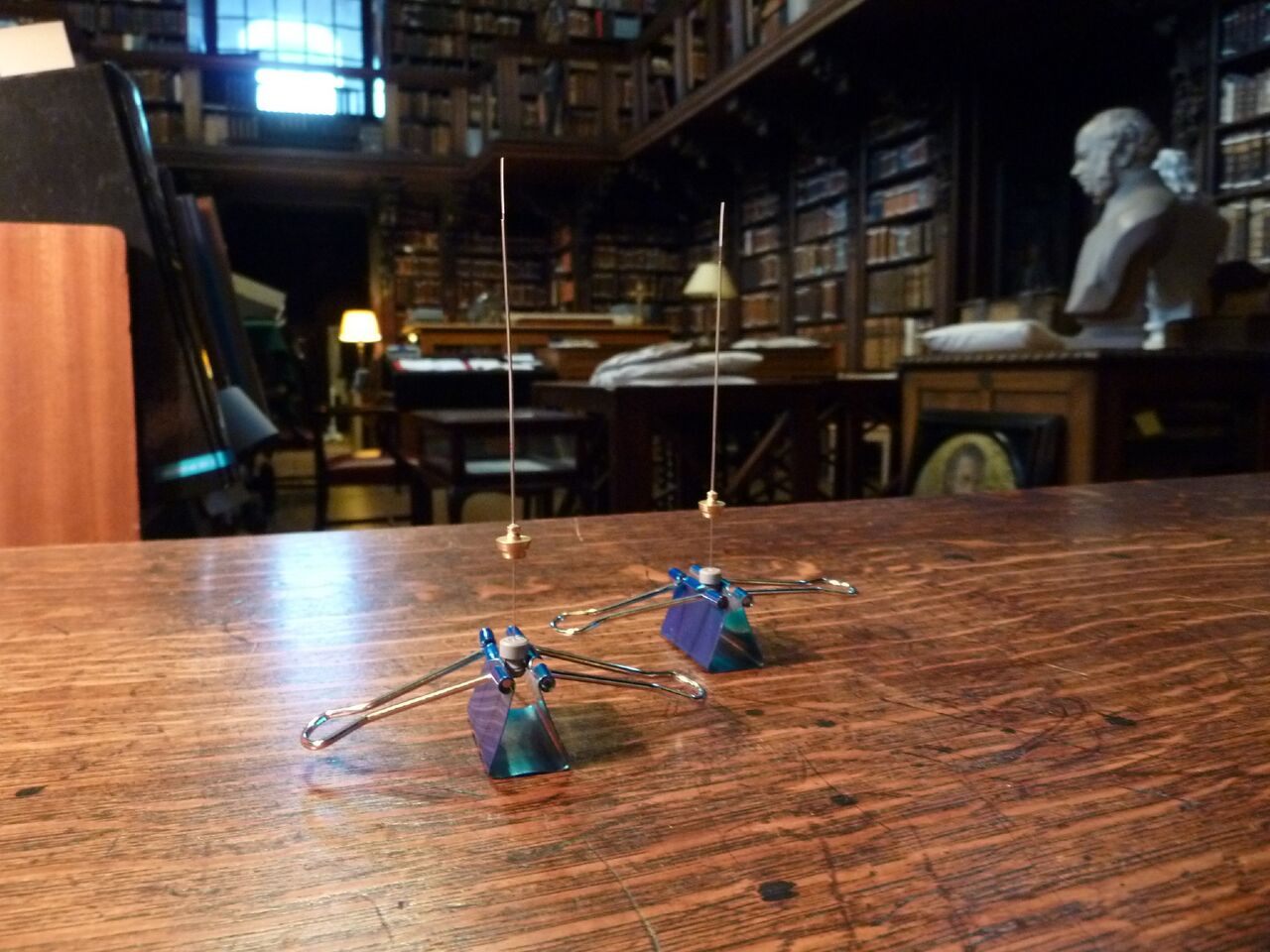

Scent-collecting fibers set up to capture VOCs at St Paul’s Cathedral Library. (Photo: Courtesy of Cecilia Bembibre)

A veritable treasure trove of historic smells, Knole House is said to contain 365 rooms. The sprawling mansion has the added benefit of an extensive family archive, which offers the researchers valuable historical context for the objects they are sniffing.

Bembibre has selected a handful of objects and atmospheres to test there, including a pair of fringed, leather gloves from the 1800s (“I think the gloves might have been perfumed”); a unique 1750s potpourri recipe found in the archives; the wax used to polish the furniture; the smell of the “Venetian Ambassador” room; an old book; and more modern smells, like a vinyl record from the family’s collection.

But how do you even go about recording a smell?

Bembibre uses several different methods to capture a smell for study. One is known as the Headspace technique, wherein an object is placed inside a clean, sealed bag that has a valve on it, sealing in the volatile organic compounds, or VOCs. Then an absorbent carbon fiber is inserted into the valve to soak up the ambient VOCs that have been isolated inside. She also uses another method, known as passive diffusion, which involves leaving a sort of carbon sponge in a space and allowing it to just soak up the nearby smells.

Once the VOC-laden sample is ready, Bembibre runs it through a gas chromatographer and mass spectrometer, which she describes as a “big nose.” In the end, she is left with a sort of electrocardiogram, but for smells, which she can use to identify the various chemicals in a smell. “It would be like having a recipe, and maybe in 100 years, someone wanted to reproduce that smell, they could look at that recipe,” she says.

Knole House. But what does it smell like? (Photo: Martin Stitchener/CC BY 2.0)

The analyses can be surprising. For example, the smell of an old book is primarily made up of chemicals like acetic acid, which smells like vinegar; furfural (“It smells sweet, like bread and almonds. It’s a very pleasant book smell”); benzaldehyde (“It has a very sweet, almond-y, cinnamon-y smell even. It smells of food”); vanillin, which smells of vanilla; and hexanol, which has been likened to freshly cut grass.

Taken all together, these chemicals, many of which are a product of cellular decay, create what we think of as the old book smell. “It’s a smell that we appreciate, but it’s also the smell of the books dying,” says Bembibre.

One of her research partners, the company Odournet, works with an adapted chromatographer that allows Bembibre, and other researchers, to actually smell each component as it is processed. She says that it’s a heady experience, with scents coming at you so fast that it’s hard to accurately identify them—no easy feat to begin with.

Because our olfactory senses are so closely tied to context, identifying scents just by their chemical make-up doesn’t do us a whole lot of good, when it comes to the historical record. “Smells are anchored in a time and a place, so it’s not enough to have the chemical information for a smell,” says Bembibre. “We also need to know if people thought that smell was pleasant or unpleasant, strong or weak; if it had some sort of cultural associations; if it was unique or familiar; if people thought it was worth keeping or not, and why.”

Cecilia Bembibre sniffs the smells of St Paul’s Cathedral Library. (Photo: Courtesy of Cecilia Bembibre)

Opinion plays a significant part in the analysis, too. Bembibre is far from scent-agnostic, though; she has smells she loves and odors she hates, just like the rest of us.

‘There is a smell I really dislike, which is the smell of butyric acid. You find it in human sweat in a low concentration. You also find it in Hershey’s chocolate, the Kisses,” she says. “I’m always going to the States and thinking, ‘How can they be so popular? How can people like them so much?’ If you grew up celebrating with this chocolate, you obviously love it.”

Beyond the academic importance of smell, she’s interested in sussing out “the personal associations, because they’re part of why we think smell is worth keeping,” she says.

In addition to her studies, Bembibre currently leads “smellwalks” that bring people closer to the unique scents of their world. Smells are the most visceral aspects of the human experience, and yet we lose them everyday. As the technology gets better, though, hopefully we can begin to preserve our own precious scents.

Bembibre has her own special scent memory she wishes she could preserve. “I have a small child, and we’ve just been on holiday to the beach. You know the smell of skin when you come back from a day at the beach and it’s a bit salty, and there’s the sun and the cream?” she asks.

“It was just a lazy family holiday that brought me back to my own childhood. I’d love to collect that smell.”

Correction 09/21/16: Previous references to spectrometers have been changed to clarify that the instruments are actually chromatographers.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook