Meet the World’s Most Controversial Inflatable Yellow Duck

If you were to come across “Rubber Duck” floating placidly in the harbor of your major city, you would probably, like most people, stop and stare for a bit. You might admire the way its roundness contrasts with the angularity of its fellow vessels, and how its smooth yellow head stands out against the sky. You might chuckle at how it makes the whole port look like one big bathtub.

You probably wouldn’t think, in this world of Jeff Koons’s Balloon Dogs and Damien Hirst’s expensive art sharks, “wow, this must be among the most divisive creaturely artworks in the modern pantheon.” But it is.

“Rubber Duck” is the creation of Dutch sculptor Florentijn Hofman, and is, in the words of one of its most vocal critics, “easily the most visible public conceptual artwork in the world today.” When the duck visits cities, hundreds of thousands of people flock to visit it.

But where some see joy and innocence, others see a scourge on the landscape. One critic in Belgium chose to let actions speak louder than words, and stabbed it 42 times in the dead of night. This caused community members to rally around it, establishing a Giant Duck Night Watch for the remainder of its term.

Why do we love this duck so much? Why do we hate it? And, perhaps most importantly, why can’t we escape it?

A sojourn in Seoul. (Photo: Travel Oriented/Flickr CC-BY 2.0)

A sojourn in Seoul. (Photo: Travel Oriented/Flickr CC-BY 2.0)

In art years, “Rubber Duck” is only a baby. Its first public appearance was back in 2007, in Saint-Nazaire, France. Nestled comfortably into the Loire River harbor, perky tail feathers abutting old German U-Boat pens, the duck “became the mascot” of an annual arts festival simply by gazing serenely at onlookers and being 100 feet tall.

In the following years, rubber ducks made their way to Brazil, Australia, New Zealand, Vietnam, Canada, and elsewhere. People all over the world were drawn in. When one got to Hong Kong’s Victoria Harbor for a monthlong stint in spring 2013, a swarm of expectant fans had somehow found the test inflation site, “a shipyard like 20 minutes outside the city,” and were lining up to shoot photos, Hofman told Bloomberg.

By the time it reached Azerbaijan in late 2013, one journalist touted it as a “worldwide celebrity.” The Chrysler Museum of Art, host of the duck’s May 2014 trip to Norfolk, Virginia, seems almost bemused by its success: “We set attendance records every day,” the museum’s website announced. “We sold what we thought would be two weeks worth of souvenir merchandise in a day and a half. We had people taking pictures at a rate of 2,500 per hour… Crowds were present at all hours of the day.”

The duck draws crowds in Sydney. (Photo: Alfred Hernandez/Flickr CC-BY 2.0)

The duck draws crowds in Sydney. (Photo: Alfred Hernandez/Flickr CC-BY 2.0)

But, ironically, the duck’s biggest sin may be its own ubiquity. Art and architecture critic Kriston Capps argues that the sculpture has nothing to do with any particular space—its message is the same wherever it is, which defeats the purpose of place-based art. “When it’s done right, public art expresses some unique value about a city’s particular cultural vantage point,” he writes on Citylab. “Rubber Duck has all the nutritional value and regional identity of a Diet Coke.”

The instantly recognizable features that made the duck a great toy can also make it seem like lousy art. “With the repetition… it feels like it’s almost become more of a meme,” Donovan Hohn, author of Moby Duck, said in a phone interview.“It feels like advertising, the way that people like to look out for the Goodyear Blimp. For me it becomes less interesting the more he does it.”

But why do we love rubber ducks so much? Where did they come from, and when exactly did their body mass start increasing so dramatically?

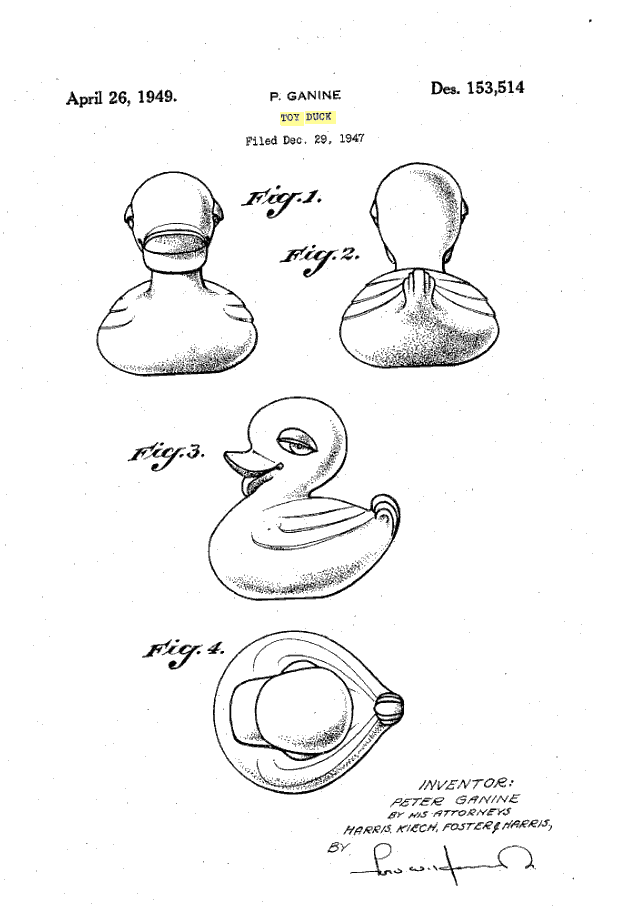

Ganine’s rubber duck patent application, featuring his original design. (Image: US Patent Office/Public Domain)

Ganine’s rubber duck patent application, featuring his original design. (Image: US Patent Office/Public Domain)

The story of the rubber duck starts small. In the late 19th century, following rubber’s introduction to the marketplace, many people decided, apparently independently, to shape the new material into ducks. Patents floated by every couple of decades—there were rubber duck hunting decoys, ducks that couldn’t fall over, and hollow duck-shaped bath toys with holes in them that could be squeezed “to produce an attractive fountain-like effect, and also to enable the playing of pranks by one person upon another.” For whatever reason, none of them quite took off.

Eventually, a sculptor named Peter Ganine began experimenting with ducks too. Ganine was an inveterate anthropomorphizer—he is most famous for redesigning the chess set by adding “austere, thoughtful faces” to the pieces, and for a grinning whale toy that won him a design prize from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In 1949, he patented a toy that finally brought all the rubber duck’s most salient features together. His version squeaked, floated, stayed upright, and, perhaps most importantly, smiled. He sold millions of them.

Soon, the cute yellow creatures were synonymous with childhood, for a few major reasons. Their natural habitat is the bathtub, where most people don’t hang out after a certain age, and so they’re inextricably associated with a splashier, more innocent time, says the National Toy Hall of Fame. They also have an immediate psychological effect on us. Primary colors, smiling faces, and baby animals all “have the almost narcotic power to induce feelings of happiness in the human brain,” Hohn writes in Moby Duck, a book about his experiences chasing a flock of normal-sized rubber ducks lost at sea after a shipping accident.

Little Richard adds some rock and roll cool to “Rubber Duckie” in 1993.

Plus, there’s that distinctive squeak. It’s an effective enough combo that “Rubber Duckie,” a song written for the children’s show Sesame Street, hit #11 on the generally adult-oriented Billboard Hot 100 chart in 1971.

Ducks are also a cultural blank slate. Unlike even the teddy bear (which used to mean you had the fuzzies for President Roosevelt), or the lawn flamingo (flush with class-related undertones), the rubber duck has always just been a basic bath toy—it’s ceaseless presence and its historical and emotional smoothness make it the epitome of its category. “In the bestiary of American childhood, there is now no creature more iconic than the rubber duck,” writes Hohn.

The rubber duck is so ubiquitous it serves as a kind of non-statement, a red-beaked blank slate upon which individuals can perch whatever type of identifying characteristic best encapsulates the message they hope to send. That’s why tchotchke shops are full of ducks wearing sports jerseys and city paraphernalia, charities worldwide can safely adopt them as symbols, and computer programmers use “rubber-ducking” as shorthand for “explaining something to a non-human interface.”

The rage-inducing waterfowl visits Rotterdam in 2008. (Photo: Mirko Tobias Schafer/Flickr CC-BY 2.0)

The rage-inducing waterfowl visits Rotterdam in 2008. (Photo: Mirko Tobias Schafer/Flickr CC-BY 2.0)

Sculptor Florentijn Hofman counts on all of these attributes for his controversial ducks’ success. But instead of a hat or a prop, its special sauce is sheer size. “By making huge sculptures, you downsize the human,” Hofman told Bloomberg last year. “That takes away our ego and makes us communicate easier with each other.”

Hohn, remembering his own duck-chasing experiences, thinks there’s an element of taming the wild in there, too. “So much of the ocean feels really inhuman and hard to comprehend,” he says, “so there’s something about a toy duck washed up on a wild beach somewhere, or this giant duck on the ocean, that humanizes it.” The duck’s artificial sublimity and natural appeal ushers in warm associations for people from Azerbaijan to New Zealand.

Which, some argue, is exactly the opposite of the point. Not only does the duck’s omnipresence not discriminate between cities, it also locks many of their citizens out of the revenue stream. Hofman’s decision to enforce copyright over all rubber ducks when his art project is in town funnels the cash flow it generates into certain approved channels, and he and his organizers have been known to sue people over infringement, or even to saddle up ol’ Quacky and leave town.

“It makes me crazy to see this show arrive to cities, deprive all of the local businesspeople from the income that these spectacles generates… and then kind of take off,” Capps said in a phone interview. “I can’t believe people don’t see rage when they see these rubber ducks.”

The iconic Tiananmen Square photo, duck-tered by a satirist. (Image: Imgur/Weibo)

The iconic Tiananmen Square photo, duck-tered by a satirist. (Image: Imgur/Weibo)

The duck’s salvation may come in its limited, and somewhat accidental, capacity to surprise. Its iconicity can still be subverted and localized—in 2013, Chinese authorities banned searches for “giant yellow duck” after an artist subbed the sculpture in for tanks in an infamous photo of Tiananmen Square. It also can pull some physical tricks. The statue is made out of a hollow PVC pipe skeleton, seated on a giant pontoon and wrapped in plastic that blows up with the help of a generator.

Thanks to a computer in its head, the duck automatically deflates again when wind speeds become threatening, so that one of the first art critics to look for it instead saw it as a giant yellow puddle. Ducks have also deflated, for various reasons, in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Philadelphia (“It’s like a very large bicycle tube,” said one man tasked with patching Philly’s). In 2014, a typhoon sunk a duck in Guiyang, China, and it was never found. Such performances, Hohn says, make it a bit more interesting: “maybe I’ve kind of been hoping that’s what’ll happen to it.”

After all, when a legend swells up this big, what is left for it to do but pop?

The duck deflates in Taiwan.

Naturecultures is a weekly column that explores the changing relationships between humanity and wilder things. Have something you want covered (or uncovered)? Send tips to [email protected].

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook