Was Minnie Dean Really the Wickedest Woman in New Zealand History?

Revisiting the case of the only woman ever executed on its shores.

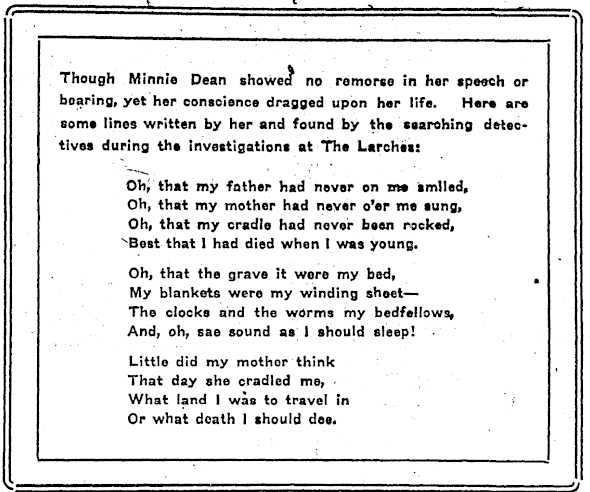

No flowers grow on the grave of Minnie Dean, the baby farmer. She killed her charges with abandon, and a hatpin. She was the daughter of a clergyman, but bound for hell. She was wicked and wanton, and deserved to die. And if you were a naughty child growing up in Southland, New Zealand, she was coming to get you.

Despite 120-odd years of circulation, almost none of these “facts” about Dean, born Williamina McCulloch sometime around 1844, are true, according to historian Lynley Hood, author of Minnie Dean: Her Life and Crimes. Dean was the daughter of a train conductor, but passed herself off as educated and middle class. She was desperate and impetuous, though probably not evil—and hatpins didn’t come to New Zealand until well after her arrest. “In fact,” Hood writes, “there is no evidence that Minnie Dean ever stabbed anyone with anything.” She was, and likely will remain, the only woman in New Zealand ever to be executed. For decades, stories of Dean’s murderous spirit hung heavy over Winton, a southern town 20 miles from Invercargill, the city where she was tried and put to death.

Here is what we do know. Dean offered unwanted small children a home, for a fee, and some 27 of them passed through her life. Ten are known to have survived, six are thought to have died, three are unaccounted for despite efforts to find them, and the remaining eight—who knows? According to Te Ara, the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, “Dean claimed that seven children were adopted by families who wished to keep the adoptions secret. The police and the public believed that the missing children were murdered.” Either way, three tiny bodies were found buried in her garden, and two of those deaths were at the center of an 1895 trial that shook the nation. Even decades later, in 1922, a journalist writing for the New Zealand Truth stated: “No more remarkable series of crimes [was ever] committed in Australasia, few more remarkable in the world.”

Today, we might call Dean a foster parent, but back then, she was what was rather callously known as a “baby farmer.” At the time, an illegitimate child was a path to social ostracism—and in Scotland, where Dean and many of these early settlers to New Zealand had come from, a concealed, out-of-wedlock pregnancy that resulted in an adoption could result in death or banishment for the disgraced mother, if she was found out. But just “£10 or £20 to someone like Minnie Dean could solve the problem,” writes New Zealand historian James Belich. Desperate families would pay baby farmers a lump sum or a monthly stipend, or both, to assume care of the unwanted child. At least 16 of Dean’s charges are known to have been born out of wedlock.

Baby farmers may have provided homes, even loving ones, for those children, but more importantly, they relieved the biological mothers of the consequences. “It was quietly accepted that the child’s chances of survival were not good,” Belich adds, though Hood disagrees. “They confidently believed that their unfortunate offspring would be under the charge of one who would, in every respect, prove a kind and exemplary mother,” she writes.

Dean lived in near-destitution with her husband, Charles Dean, deep in New Zealand’s South Island. She is now thought to have come alone from Scotland to conceal an illegitimate child of her own. Save for an aunt, she knew almost no one in Southland except Charles, whom she met there. At the very bottom of the earth—dark, damp, remote—they sought to make a life for themselves on the frontiers of Western civilization. Charles is sometimes described by historians as an alcoholic, and he was certainly extremely bad with money. Papers at the time called him “mild and weak” or “feckless and dull.” The couple slipped in and out of bankruptcy, and eventually moved to Winton with nothing but the clothes on their backs. Charles found work as a laborer. Minnie’s options were more limited. She taught children locally, but turned to baby farming to make ends meet.

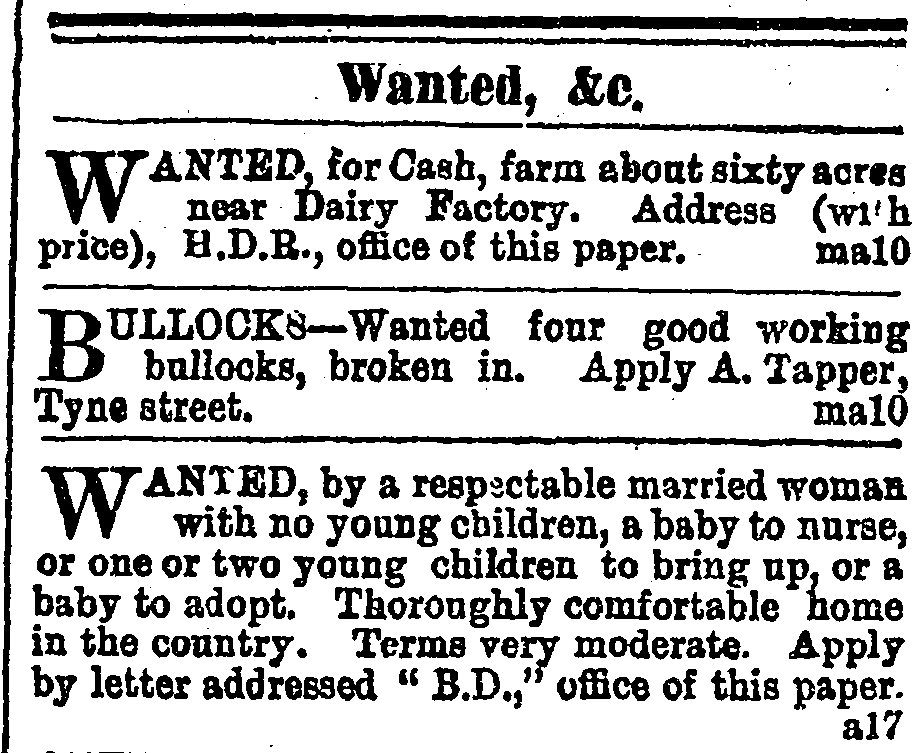

Throughout the 1880s and 1890s, Dean placed a series of anonymous advertisements in newspapers across the South Island. “A respectable married woman wants to adopt a child; comfortable home in the country,” read one. “WANTED, by a respectable married woman with no young children—a baby to nurse, or one or two young children to bring up, or a baby to adopt,” went an earlier iteration.

Dean simply did not have the means, even with payments from the biological families, to look after so many children, Hood writes. “There can be little doubt that Minnie loved her charges (though she may have loved some more than others) and she had every intention of caring for them all to the best of her ability.” This career choice was underpinned, she writes, by “a stubborn irrationality.”

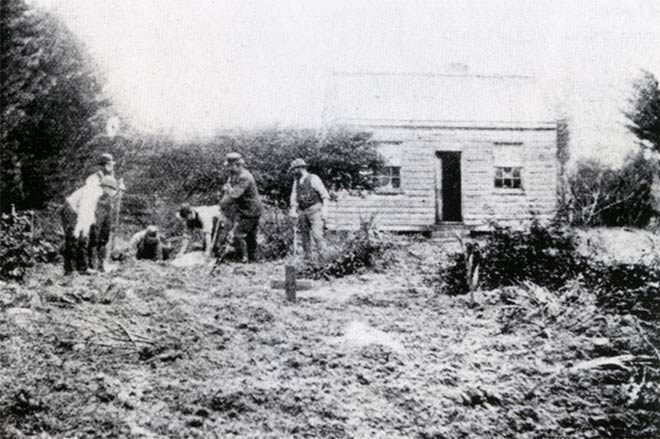

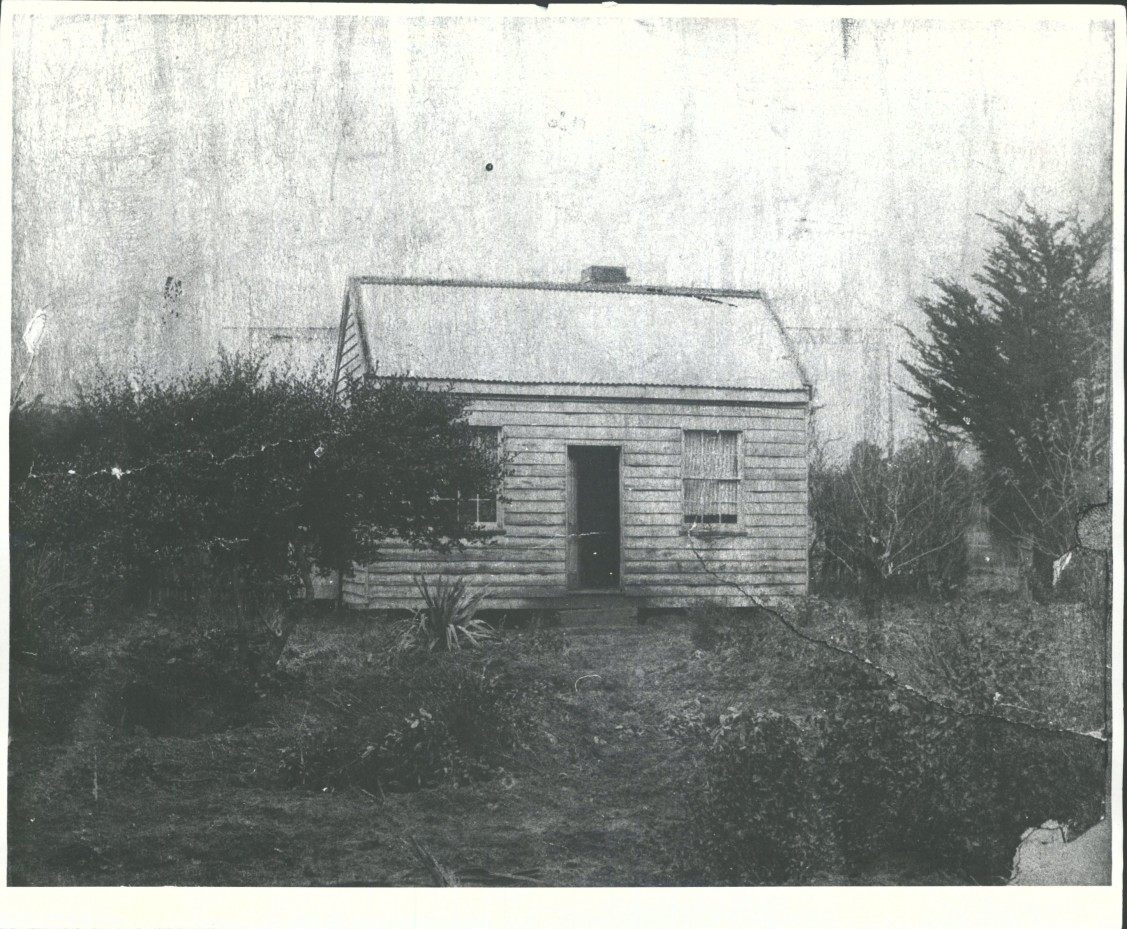

Around 1890, local police began to grow wise to the surfeit of babies at the Deans’ home, known as The Larches. At any one time, there may have been as many as nine children in her care under three years of age. The home was dirty, overcrowded, and inadequate to deal with a family even a fraction of that size. In 1889, a six-month-old baby had died. Two years later, a separate inquest deemed the cause of death of another tiny child, barely six weeks old, to have been inflammation of the heart valves and congestion of the lungs.

Police grew concerned and started watching more closely. Dean’s anonymous newspaper advertisements revealed that she was still looking for more babies. There was also evidence that she was unsuccessfully attempting to take out life insurance policies on them (which wouldn’t have been especially unusual). By 1893, Dean had attracted still more attention, culminating in a letter from the commissioner of police to the Minister of Justice. A flood of babies were believed to be entering the Deans’ home—and no one knew exactly what was happening to them. Dean became more and more furtive.

In 1895, the police found something. On May 2, a railway news agent spotted Dean boarding a train and carrying a baby and a hatbox. On the return trip, the baby was gone, and the hatbox appeared suspiciously heavy. In a 53-page statement written while awaiting trial, Dean stated: “When I got on the train, I laid the child down on the cushions. She was asleep.” Before boarding the evening train, she had dosed the sickly infant with laudanum, an opiate commonly given to children to ease coughing or agitation. But she had misjudged the quantity. Later on the journey, she looked over and realized the child was dead. Dean panicked. That night, in a hotel room, she stuffed the body in the box, tied it up, and, writes Hood, “set off for the railway station with her hat box, purse and parcel as if nothing had happened.”

The news agent summoned the police, who searched fruitlessly along the tracks for the baby. Eventually, they found her corpse in Dean’s garden, buried alongside the bodies of two more young children. One was recently deceased, and the other a skeleton, from an older boy Dean claimed had drowned. The following month, Dean went on trial for murder, amid a media frenzy. “You can’t get past that public outcry over a woman harming kids in her care,” says New Zealand historian Bronwyn Dalley. There was outrage, certainly, but also the titillation and novelty of having a woman on the stand, facing serious charges. “This was the time when sensationalist crime reporting was booming, and many cases were presented in the papers quite theatrically,” Dalley adds. Outside the courts, enterprising locals sold grisly souvenirs—baby dolls in hatboxes.

Dean was presented as a murdering monster, but more than that, says Dalley, “there was a real groundswell of opinion over baby-farming,” with other high-profile cases overseas—involving high volume and neglect—sparking massive public and police interest in the practice in New Zealand. All of this likely contributed to the outcome of Dean’s trial, and her place as the only woman in the country to be actually executed. (At least three other women had previously been sentenced to death for child murder, but had their sentences reduced to life imprisonment.)

On the morning of August 12, 1895, Dean was hanged in Invercargill. It was midwinter, around the last dregs of the morning’s sunrise. At 7:57 a.m. she was escorted to a private gallows by a gaoler, surgeon, chaplain, sheriff, and hangman. A crowd swarmed outside the prison walls, even though nothing could be seen or heard. The sheriff asked whether she had any final words. “No,” said Dean, “except that I am innocent.” As she fell through the trap door, newspapers reported that she cried out: “Oh; God, let me not suffer!”

Dean was dead, and the New Zealand police sought to put an end to the practice of baby farming. She had directly inspired the 1893 Infant Life Protection Act, says Dalley. “Anyone who took in kids under two for more than three consecutive days with payment had to be registered as a foster home and were inspected by the police.” A few years later, in 1896, this was expanded to children under the age of four. But its effectiveness was curtailed by the many demands already on the police, says Dalley, who were “way too busy and unskilled to be trotting round inspecting the care of homes where kids [were] kept.”

For almost a century, Dean was widely considered a kind of bogeyman, a specter to help get kids to behave. But in the 1980s, a television series screened in New Zealand began to spark queries about her guilt—or, rather, her innocence. Next, Hood’s book, published 99 years after Dean’s death, revealed that most of what was thought to be known about Dean, including her origins, how she got to New Zealand, and her crimes, were fictitious. Hood’s sustained research revealed desperation and optimism to be more realistic motives than bloodlust, coupled with the not atypical use of laudanum to calm the children in her care. “Whether the real Minnie Dean deserves her terrible place in New Zealand’s folklore is far from certain,” writes Hood. In 2009, a distant Scottish relative paid for Dean to have a headstone on her unmarked grave in Winton cemetery.

Whether all of this has changed public opinion of one of New Zealand’s most notorious criminals, memorialized on stage, in verse, and on screen, remains to be seen. “There is a power in the stories people tell to explain things, and to guard against things, or to make things special,” says Dalley, “and no end of ‘truth,’ and I use the word advisedly, will change that.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook