Plumbing the Secrets of the Archives of the Museum of Modern Art

From an Avenue of Fascism, to turtle soup, to a phantom photo of three important women having tea.

Over its 90 years of existence, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York has acquired an astonishing collection, with more than 3,500 paintings and sculptures, 11,000 works on paper, and 60,000 prints and multiples. But its holdings go much deeper. “We estimate we have something like 6.5 million items,” the museum’s Chief of Archives, Library, and Research Collections, Michelle Elligott, says of her department’s files. “That’s not a very precise estimate, because I have not gone in to count every single one of them, but it gives you a sense of its expansiveness and depth.”

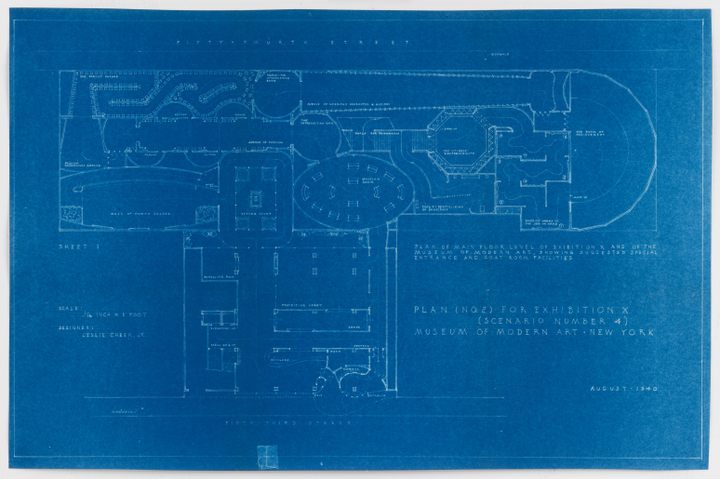

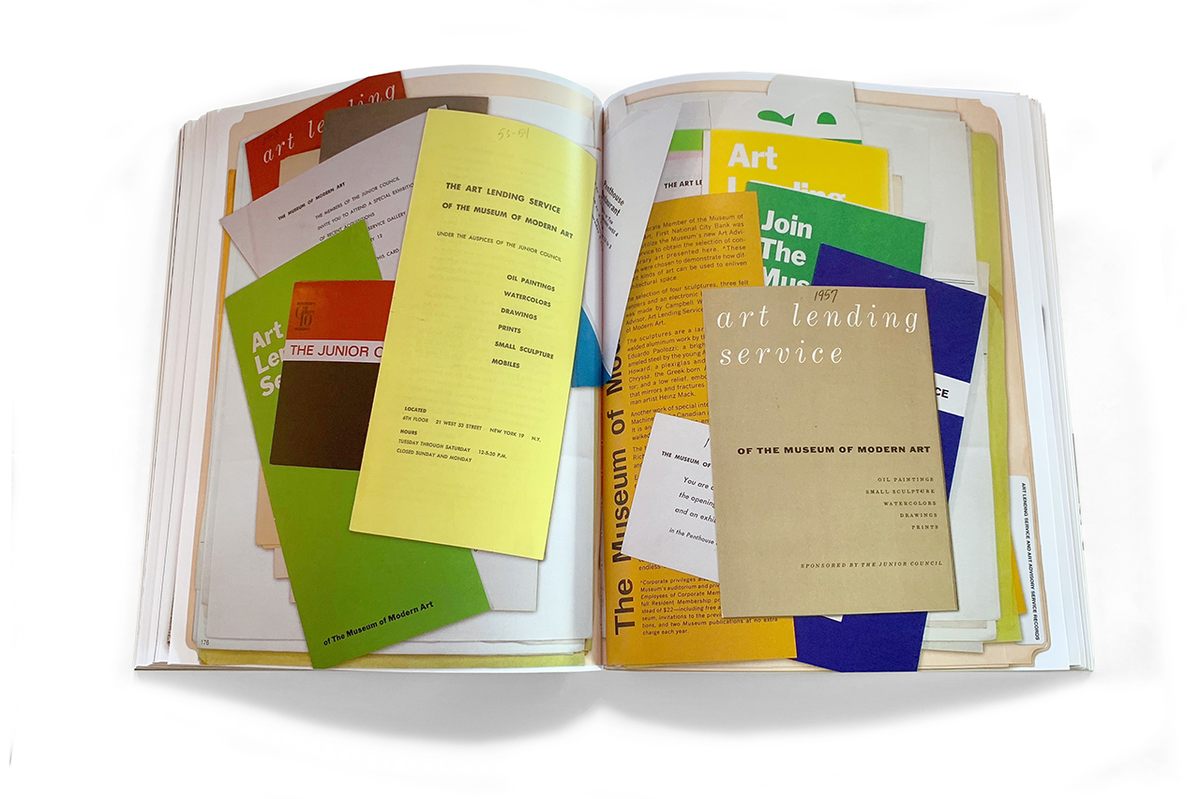

Letters, telegrams, memos, oral histories, gallery records, and hundreds of thousands of photographs: The archives contain a multifarious history of modern art, and suggest MoMA’s role in shaping it. They are a treasure trove of behind-the-scenes activities, unrealized plans, and unusual initiatives, as a new book, Modern Artifacts, makes clear. It compiles 18 columns that Elligott wrote for art magazine Esopus from 2006 to 2019 that delve into obscure chapters in the museum’s history, from the mysterious (and never-realized) Exhibition X it planned in 1940 in response to World War II, to the Art Lending Service that it operated for decades, which allowed private individuals to rent and purchase pieces consigned by galleries.

Edited and designed by Esopus founder Tod Lippy, Modern Artifacts also reproduces hundreds of documents from the museum’s archives, as well as projects by artists such as Mary Ellen Carroll, Clifford Owens, and Michael Rakowitz that respond to them. Atlas Obscura spoke with Elligott, who has been involved with MoMA’s archives since 1995, about the book and her work.

There are many wild stories in the book. Let’s start with Exhibition X. Abby Aldrich Rockefeller had the idea for it?

She was one of our great founders and trustees. This was the summer of 1940. Paris had just fallen to Hitler, and Mussolini had just agreed to join the Axis Powers. And this was still the moment when the United States was in its isolationist stance. The museum said, “This is a very serious situation. We can’t let fascist regimes take over the world.” Its approach was, we are a museum so we are a purveyor of ideas and not arms, but we could come up with a—if you will—propaganda show or something to try to urge the American public to get on board and stand up and fight for the ideals of democracy and freedom of expression.

You show drawings and even a treatment for the show, which sounds like it would have been intense—a multimedia extravaganza. The official title alone, For Us the Living, is dramatic.

It was going to be this physically immense, immersive exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art that was going to have no art, per se. The museum visitors would be invited into the show and travel from one gallery to another, being introduced to some of the issues behind the conflict. You would, for example, traverse the Avenue of Fascism, which had a portrait of Hitler at the end and mechanized dummies on either side against the walls that would spin and salute Hitler. At one point you’re put in a gallery where a booming voice says, “Who is it who has allowed this to happen?” There’s a spotlight overhead. The lights go off and—are you ready for this?—the walls rotate. They become mirrors, and the lights come back on and the booming voice says, “It is you who have neglected your duties!” So if that doesn’t spur you to action, I don’t know what would.

But, of course, it never happened.

Why was that?

It was going to be quite a pretty penny for that time. It was three quarters of a million dollars in 1940 dollars. But two things also happen. First of all, the executive committee of the board of trustees was briefed on Exhibition X, but they never informed the rest of the trustees. And you know how, with governing boards, there can be internal politics. I think that absolutely had to play some part in it. Secondly, there’s a 40-page manuscript that was a narrative for what was supposed to be happening in each of these galleries, and Abby Aldrich Rockefeller says, “Well, I’ve read the manuscript, and to me, it feels more like a motion picture than a museum exhibition,” which is not terribly off-base.

Despite that show being scuttled, the museum was involved in the conflict.

The museum had this wonderful program, the War Veterans’ Art Center, devoted to helping veterans recovering from PTSD and physical ailments by doing art therapy. They found that weaving was very good to help rehabilitation, like if someone had a hand broken. There was painting, there was clay-making, making ceramics—just providing a space for healing.

The photos from that are incredible—one man is weaving shirtless, and a few sailors are in uniform as they finger paint. Were there any surprises for you while working on the columns?

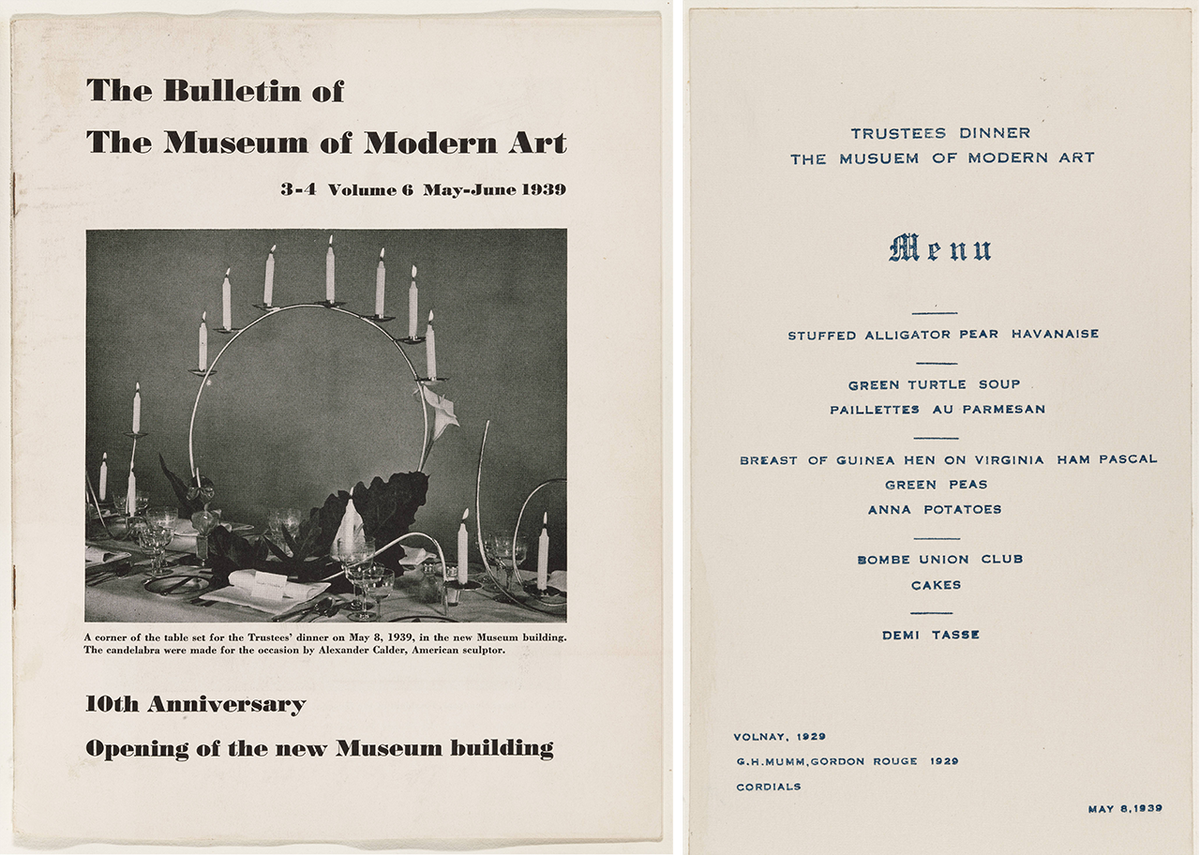

It was shocking to me that the museum served turtle soup at its 10th-anniversary opening dinner in 1939.

The materials from that celebration are superb—the menu, the photo of Alexander Calder’s candelabras, the notice that the president would be speaking.

We have the recording of that radio broadcast from the White House, where President Franklin Delano Roosevelt talks about the importance of the arts and the democracy—a very powerful, powerful speech.

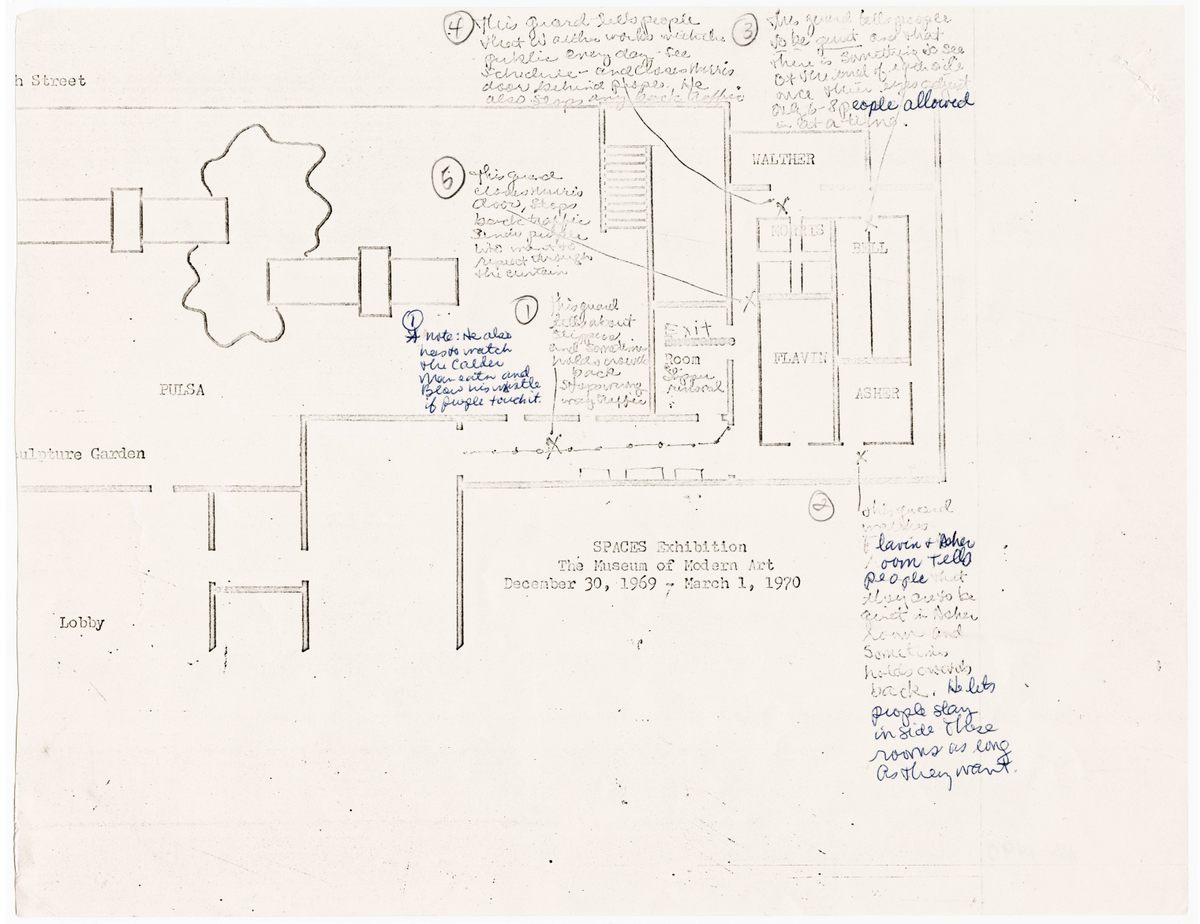

Here’s another surprise. I had been interested in the exhibition Spaces by Jenny Licht from 1969. It’s the museum’s first encounter with installation art, quote-unquote. Site-specific work.

A now-legendary show, with Dan Flavin, Michael Asher, and Franz Erhard Walther, among others.

The thing I did find that was really fascinating was the curatorial assistant writing a memo to the security supervisor—it’s like six or seven paragraphs, accompanied by the floorplan of the galleries with all these notes. With these installations, each of the rooms had a different set of guidelines for what the visitor could or could not do. This one you could enter but not speak. This one you could speak and sit down. It was a very different art experience. MoMA had never had that—you’d walk into the gallery and look at your painting. You didn’t have to educate the guards about what they could allow the public to do. That memo sort of encapsulates from yesterday to where we are today, because the art world is just so changed into this experiential, sensorial, interactive place.

One of the charms of the book is being able to decipher handwritten notes and scrawls like that, but they must be rarer now. How do you collect material in the digital era?

We have launched what we call MERA—MoMA Electronic Records Archives. We counsel individuals about what kinds of materials we would like to collect, and then they just use the software to transfer it into our digital repository. One could argue we might get much more now, in the sense that a lot of what happens in email used to happen on the phone. So that never made it into the archives.

Is there anything that’s not in the archives that you wish you had?

The good news is there’s not a clear, major gap that springs to mind right away. One thing that we get many questions about is something that probably never existed. The museum was the idea of these three very visionary women—Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, Lillie Bliss, and Mary Quinn Sullivan—and I can’t tell you the amount of times I get asked for the picture of the three ladies together discussing the foundation of the museum, or the three ladies having tea together. It doesn’t exist.

What should people know about the work you do?

The thing I love about archives is that, to me, it humanizes art history. It’s a way to connect with the people, the makers—the why, the wherefore. And also, it makes a towering historical figure modest or humble, because he or she also went day to day and wrote notes on the back of a napkin or something.

The interview has been edited and condensed.

* Correction: The original version of a caption in this story made reference to “stuffed alligator.” The menu actually read “stuffed alligator pear,” which is an avocado.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook