Morbid Monday: La Santa Muerte, the Skeleton Saint

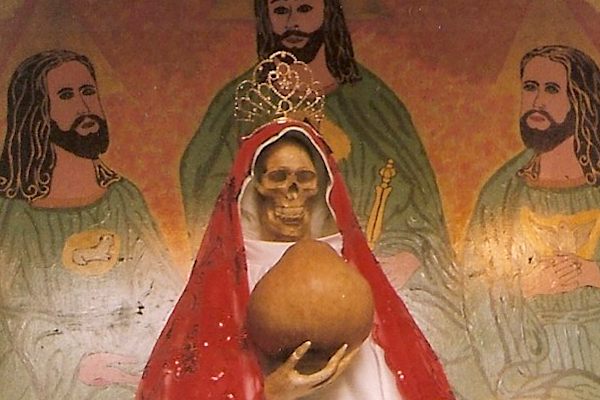

La Santa Muerte in El Santuario National del Angel de la Santa Muerte (photograph by Laetitia Barbier)

On October 15th, 2009, I took off from freezing Europe for two months of adventures, achieving a longtime personal fantasy: a solo journey to Mexico to survey death and its myriad avatars, from the historical past of the country to its contemporary culture, surveying domains like criminology, religion, the arts, and even wrestling. Once I arrived in Mexico, I realized I wouldn’t have to dig too deep, since the visual of the macabre was pretty much everywhere — in the gruesome daily news depicting the intimidation crimes of drug trade, in the religious icons and their bleeding martyrdom, and in the merry vividness of Dia de Los Muertos iconography.

The Aztec Templo Mayor was excavated in 1978 in the historical heart of Mexico City. Dedicated in part to Huitzilopochtli, the god of war, it has stone-carved skulls. (via Attraction Uptake)

José Guadalupe Posada, “Gran calavera eléctrica” (“Grand electric skull”) (c. 1900). This print shows a large skeleton hypnotizing a group of skulls and a sitting skeleton while an electric street car, with skeletons as passengers, passes in the background. (courtesy Library of Congress, via Wikimedia)

Wherever I set my eyes were skulls and reminiscences of blood spilled by Aztec human sacrifices or the heroes of the Revolution. Death was like a revered sacred presence. Varying in forms, it felt like an obsessive leitmotiv, palpable and unexpected.

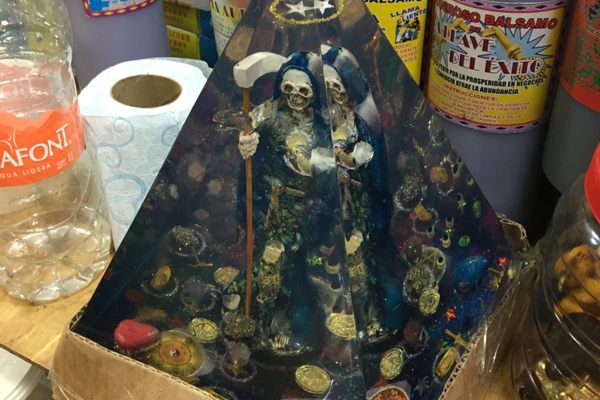

A marketplace shrine to Santa Muerte. (via Patricio López/Flickr)

One of my most fascinating experience happened a few days after my arrival, at a street shrine in the historical center of Mexico City. Very humbly, the usual candles and votive offering were disposed on a table, surrounding a dignified statue of a saint I had never encountered in Europe. A life-size skeleton in a sumptuous white dress, surrounded by rosaries and fresh flowers and also cigarettes and glass shots filled with what looked like Tequila.

My jaw dropped. It was, of course, La Santa Muerte, the Holy Death revered by a certain part of the Mexican population. At the time, I didn’t know so much about the “Bony Lady” and always thought it was a secret vernacular belief. After stumbling upon four different shrines dedicated to her in the same day, I realized I was wrong.

La Santa Muerte (photograph by Francis Mckee/Flickr)

The starting point of the Santa Muerte phenomenon is a matter of debate, but its explosion in popularity is fairly recent. In 2001, a woman named Enriqueta Romero initiated the first public shrine in Tepito, one of the fiercest boroughs of Mexico City. The shrine made official her devotion to the “White Girl,” as well the devotion of hundreds of other believers who had long celebrated in secret.

But some linked the syncretic origins of the Santa Muerte with the Catholic tradition of “memento mori” and the continuation of Aztec beliefs in the goddess Mictecacihuatl, the Queen of the Underworld. This Meso-American lineage could explain why La Santa Muerte is a feminine figure in Mexico while her other counterparts in Argentina (San La Muerte) and in Guatemala (Rey Pascualito Muerte) are male.

On the left, Mictecacihuatl, the Aztec godess of death. (courtesy Archivo de Miguel Covarrubias, Universidad de las Americas, Puebla, via Myriam B. Mahiques )

The Santa Muerte cult is genuinely Mexican, spread largely all around the country, as well as in South California and more discreetly in other parts of the United States where the Latino American population is important. For example, in New York, Arely Vazquez Gonzalez owns a private altar decicated to La Santa Muerte in her apartment, and each August a celebration takes place with a feast and mariachi band for “her queen” and other devotees.

Arely Vazquez Gonzalez in front of her private shrine. (still from “Loving the Bone Lady,” directed in 2012 by Scott Elliott)

Although La Santa Muerte deals with a dark imagery, it has nothing to do with black magic or satanism and believers claim themselves as Catholics. In fact, La Santa Muerte is usually envisioned as a folk saint. Like the healer Niño Fidencio or the mustached patron saint of drug dealers, Jesús Malverde, these departed members of the community, usually from lower social classes, were believed to posses miracle working skills, and their cults became viral throughout the country. Being connected to the hard realities of Mexico, they often steal the thunder of the local canonized saints. Concerned about the growing numbers of her believers, the Vatican virulently condemned the Santa Muerte cult and considered its worship as blasphemous.

Why is it so popular? As Andrew Chesnut reported in his book “Devoted to Death - Santa Muerte, the Skeleton Saint:

A Mexico City vendor explained the appeal of Santa Muerte to her, saying, ‘She understands us because she is a battle axe [cabrona] like us.’ In contrast, Mexicans would never refer to the Virgin of Guadalupe as a cabrona, which is also often used to mean ‘bitch.’

Statues of La Santa Muerte (photograph by Christine Zenino/Flickr)

In just over ten years, La Santa Muerte became the main “idol of the destitute.” Tattooed on criminal arms, carried as an effigy around the neck of the poor, the sex workers, and homosexuals, Santa Muerte became the miraculous protector of those who felt rejected by the Catholic Church. But the outcasts are not her only devotees, and La Santa Muerte has gathered around her skeletal figure people from every social class. Why? Because La Santa Muerte has the reputation of being a powerful wish fulfiller who can cure every ailment, free people out of jail, and make your business a successful one.

The National Sanctuary of the Angel of Santa Muerte, in Colonia Morelos, Mexico City. (photograph by Laetitia Barbier)

My curiosity towards this odd religious practice led me to attend several different masses held in the Santuario Nacional del Ángel de la Santa Muerte in the center of Mexico City. The church was pretty archaic, with plastic garden chairs and pigeons flying around. Behind the altar, the effigy of an angel (a pale window mannequin dressed with a white robe) had replaced the Santa Muerte, which stands a bit to the side in a special alcove. I learned later that this was a choice of the church priest, who in 2007 substituted this new figure to convey a more positive and less macabre image of his congregation.

David Romo, Priest of the National Sanctuary of the Angel of Santa Muerte, in front of “The Angel of Santa Muerte.” (via Tusnius )

The ceremony resembled a traditional Catholic mass (believers have to swear that they won’t practice either Brujeria (witchcraft) nor have sinful behaviors) but had some side rituals like a grace in front of the Santa Muerte where every attendee had to ring a bell three times in front of the skinny idol. Another highlight of the Santa Muerte ceremonies occurs monthly at the Don Queta shrine in Tepito and gathers hundreds of adepts who sometimes come crawling on their knees to the sanctuary as a form of pilgrimage. After the celebration, believers give offerings to the statue, which can go range from a rosary to a joint of marijuana. Even if this one is more spectacular and involves a more elaborate ritual, I won’t recommend going to this one, since as I mentioned before, Tepito is a dangerous place.

A store outside the Santa Muerte Santuario. (photograph by Laetitia Barbier)

If you’re traveling to Mexico City and want to meet La Santa Muerte in a less religious atmosphere, you should visit the Mercado de Sonora, the esoteric/witchcraft market of the city. Here you’ll be able to explore the large array of Santa Muerte-derived products, magic soap, perfumes, candles and, effigies. After I bought one of them, the cheerful vendor sprayed my wallet with some Santa Muerte Holy Water “to protect my money and assure my wealth.”

Mercado de Sonora. (photograph by Laetitia Barbier)

Mercado de Sonora. (photograph by Laetitia Barbier)

Mercado de Sonora. (photograph by Laetitia Barbier)

Sonora Market is melting pot of vernacular beliefs, superstitions, and incredible imagery, as is the flamboyant Mexican culture. It’s a syncretic realm nourished by the country’s rich past, which gathers together the community and gives them hope in their rough daily life.

Morbid Mondays highlight macabre stories from around the world and through time, indulging in our morbid curiosity for stories from history’s darkest corners. Read more Morbid Mondays>

Join us on Twitter and follow our #morbidmonday hashtag, for new odd and macabre themes: Atlas Obscura on Twitter

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook