Soap on a Bone: How Corpse Wax Forms

The Soap Man at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History (photograph by Dave Hunt, via Smithsonian Institution)

For this edition of Morbid Monday, our series on the historical macabre, we welcome a guest post from Dolly Stolze of Strange Remains, a site that focuses on forensic anthropology and bioarchaeology.

From 1786 to 1787 the graves in Paris’ Cemetery of Innocents (Cimetière des Saints-Innocents) were dug up to move the bones to the abandoned mines beneath the City of Lights, what would become the famous Paris Catacombs. Fourcroy and Thouret, French scientists who supervised the exhumation and studied the decomposing bodies, found a waxy gray substance covering some of the children’s remains. They called it adipocere, from the Latin adeps (fat) and cere (wax).

Adipocere, also known as corpse wax or the fat of graveyards, is a product of decomposition that turns body fat into a soap-like substance. Corpse wax forms through a process called saponification and tends to develop when body fat is exposed to anaerobic bacteria in a warm, damp, alkaline environment, either in soil or water. Grave wax has a soft, greasy gray appearance when it starts to form, and as it ages the wax hardens and turns brittle. Saponification will stop the decay process in its tracks by encasing the body in this waxy material, turning it into a “soap mummy.”

Two of the most famous “soap mummies” are the Soap Lady and the Soap Man. Both were exhumed in downtown Philadelphia in 1875, when city improvements near a cemetery required some graves be exhumed. These mummies formed when water seeped into their caskets and turned their body fat into adipocere. Researchers initially believed the Soap Lady was about 40 when she died, but x-rays taken in 1986 revealed that she was probably in her late 20s. At first they believed she died in 1792 during the Yellow Fever epidemic, but the x-rays also showed pins and buttons in her clothing that were not manufactured until the 1830s.

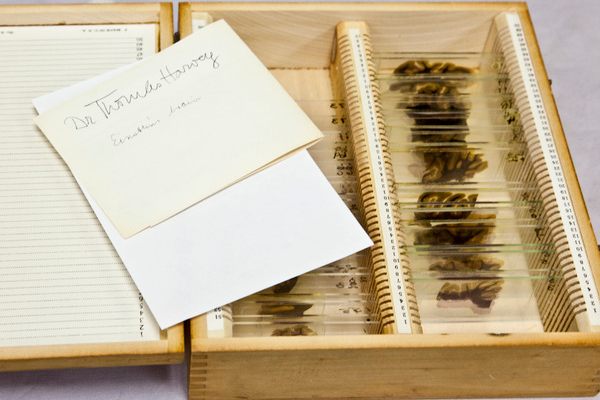

The Soap Lady is currently on display at the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia. X-ray images taken of the Soap Man reveal that he was in his 40s when he died, likely between 1800 and 1810. The Soap Man is stored in a controlled environment, stockings and all, at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. Research on both “soap mummies” is ongoing.

The Soap Lady at the Mütter Museum (photography by John Donges)

One of the weirdest cases of soap mummification was discovered in 1996, when a headless body, fully encased in grave wax, was found floating in a bay of Brienzer See in Switzerland. This torso, nicknamed “Brienzi,” baffled scientists for years because they had no idea who this person was or how long the body had been in the water.

Then in 2011, researchers from the University Zurich published the results of their investigation on the waxy remains. They found that Brienzi was a man who drowned in the lake in the 1700s. After he drowned his body floated to the bottom and was covered by sediment, where adipocere formed and coated the torso in corpse wax. Adipocere is a great research opportunity for archaeologists, but can be bad news for a graveyard

A cemetery full of soap mummies is a problem for a burial ground that needs to reuse plots every couple of decades, and was an issue for some German graveyards in 2008. It’s common practice for many German cemeteries to recycle graves every 15-25 years, when bodies are expected to be completely skeletonized. But due to the soil condition in some German cemeteries, the corpse wax buildup got so bad that bodies weren’t decomposing at all. When gravediggers started exhuming graves to turn over the plots, they found that many of the bodies had turned into soap mummies. Some cemeteries solved this macabre problem with burial chambers and expensive soil reconditioning.

For more fascinating stories of forensic anthropology, including a visit to the Paris Catacombs, visit Dolly Stolze’s Strange Remains, where a version of this article also appeared.

Morbid Mondays highlight macabre stories from around the world and through time, indulging in our morbid curiosity for stories from history’s darkest corners. Read more Morbid Mondays>

Sources:

The Soap Opera. (2013). Retrieved on February 14, 2014 from: http://www.collegeofphysicians.org/mutter-museum/collections/

Colimore, E. (2008 May 17). Learning secrets of the ‘soap lady’. Philly.com. Retrieved on February 14, 2014 from: http://articles.philly.com/2008-05-17/news/24990312_1_x-rays-forensics-yellow-fever

Parry, W. Goo of Death Helps Solve Mystery of Headless Corpse. LiveScience. Retrieved on February 14, 2014 from: http://www.livescience.com/14472-waxy-corpse-adipocere-decomposition-investigation.html

Thadeusz, F. (2008 January 7). Germany’s Tired Graveyards: A Rotten Way to Go? Spiegel Online International. Retrieved on February 14, 2014 from: http://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/germany-s-tired-graveyards-a-rotten-way-to-go-a-527134.html

Thali, M.J. Lux, B. Losch, S. (2011). ‘‘Brienzi’’–The blue Vivianite man of Switzerland: Time since death estimation of an adipocere body. Forensic Science International. 211 (2011): 34-40. Retrieved from: https://www.academia.edu/779655/_Brienzi_-_the_Blue_Vivianite_Man_of_Switzerland_Time_since_death_estimation_of_an_adipocere_body

Trescott, J. (2010 September 3). Natural History Museum’s Origins of Western Culture hall will close for a 3-year renovation. The Washington Post. Retrieved on February 14, 2014 from: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/09/02/AR2010090204957.html

Ubelaker, D.H. Zarenk, K.M. (2010). Adipocere: What is known after two centuries of Research. Forensic Science International. 2008 (2011): 167-172. Retrieved from: http://pawsoflife-org.k9handleracademy.com/Library/HRD/Ubelaker_2011.pdf

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook