The Mystery of the Missing Portrait of Robert Hooke

He was a famed 17th-century scientist. Isaac Newton was one of his rivals.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original here.

Groundbreaking discoveries in science often come with two iconic images, one representing the breakthrough and the other, the discoverer. For example, the page from Darwin’s notebook sketching the branching pattern of evolution often accompanies a portrait of Darwin in his early years, when the notebook was written. Likewise, the drawing of the orbits of the moons of Jupiter often accompanies a portrait of Galileo.

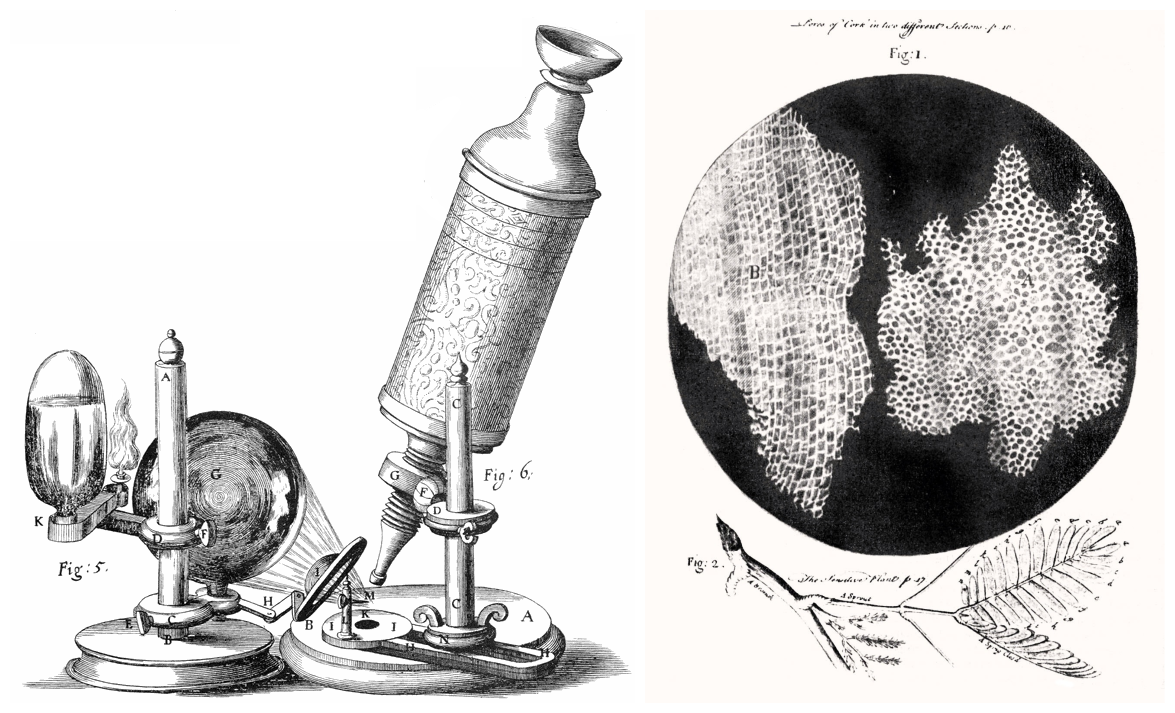

Another groundbreaking discovery in science was the discovery of the cell by Robert Hooke (1635-1703). The iconic image of the breakthrough, published in the first scientific bestseller, 1665’s Micrographia, is an etching of the cells that make up a piece of cork. It’s sliced two ways—across the grain and along the grain, showing not only the cells but also their polarity. However, there is no image of Hooke himself.

The absence of any contemporary portrait of Hooke stands out because he was a founding member, fellow, curator and secretary of the Royal Society of London, a group fundamental to the establishment of our current notion of experimental science and its reporting, which continues to the present day.

As an admirer of Hooke, I couldn’t resist putting aside my day job as a plant cell biology professor to investigate what could be called the mystery of the missing portrait. And without even setting foot in an art gallery, I think I’ve cracked the case.

I started by following up a rumor behind its absence, that none other than Isaac Newton was somehow involved in its suppression.

My hypothesis was that the portrait should show someone illustrating a mathematical principle for which Newton claimed credit—that could hint at a motive for why Newton might have suppressed a painting of a scientific rival.

The best candidate for the artist was the well-known portraitist Mary Beale, whom Hooke knew and visited, although there’s no explicit record of him sitting for her. Amazingly, when I entered the search terms “Mary Beale mathematician” online, the first link that appeared was (and still is) her “Portrait of a Mathematician.”

It matched the physical description of Hooke from contemporary sources: He was known to have gray eyes and natural brown hair that had “an excellent moist curl” and hung down over his forehead. The absence of a periwig indicates that the sitter is not nobility or of high social consequence; indeed, Hooke was one of the first professional scientists. Although he was known to have a disability, spinal curvature, the large mantle worn by the man in the painting would have covered it.

Art historians, however, believe that matching physical descriptions is insufficient to identify the sitter. This blunder was made by historian Lisa Jardine when in 2004 she misidentified a portrait of 17th-century chemist Jan Baptist Van Helmont as being Hooke.

So is there other evidence in the Beale painting besides the appearance of the sitter to support the idea that it depicts Hooke?

The sitter openly engages his audience and points to his drawing of elliptical motion. By digitally enhancing the online image, I found that the major lines match those of an unpublished 1685 manuscript by Hooke, in which he geometrically proved that a central force that is a constant, or linear, function of the distance between two bodies produces an elliptical orbit*.

In his 1687 Principia Mathematica, Newton proved the converse and claimed priority. The two men were at odds. Only Hooke possessed the drawing of his version of how things worked. It was starting to look like this painting indeed included visualizations of physics principles important to Newton, and that he might not be eager to have on public display.

Beale painted a partial view of a device on the table to the man’s left. Completing the model reveals that it is an orrery—a mechanical model of the solar system—depicting Mercury, Venus, and Earth elliptically orbiting the Sun. It’s a physical version of the drawing of elliptical motion also displayed on the table. To me, it provides further supporting evidence for the nature of the drawing and that this man is Hooke.

That Beale included the device is interesting in its own right, because she painted this portrait decades before the first modern orrery was constructed in 1704, by an instrument maker and close collaborator of Hooke, Thomas Tompion. The instrument got its name from the 4th Earl of Orrery, a relative of Robert Boyle for whom Hooke had worked prior to his employment in the Royal Society. I believe she’s painted Hooke’s prototype of an orrery here.

The landscape background, rare for Beale, presents a final clue. I hypothesized that Hooke, the city architect of London, had designed the buildings pictured in the painting. Consulting a list of Hooke’s architectural commissions from 1675 to 1685, the closest visual match was Lowther Castle and its Church of St. Michael. And indeed Hooke had redesigned the latter, with renovations completed in 1686.

The question then became whether Mary Beale could have sketched the castle and church. I was astonished to learn that she had received a remarkable commission for 30 portraits from the Lowther family, and so probably knew and sketched the castle and its grounds.

If this is indeed Hooke, the portrait provides an iconic image. So where has it been for more than 300 years?

I turned to the rumor that Newton could have been involved in the portrait’s disappearance. The two scientists did have a quarrelsome history.

One big clash was over the nature of light. Hooke explained his experiments on color as light traveling in waves through thin sheets of the mineral mica. Newton explained his experiments on color as light traveling through prisms as corpuscles or particles. They argued—was light a wave or was it particles?

Newton claimed victory, but admitted, “If I have seen further it is by standing on the sholders [sic] of Giants”—an unfortunate turn of phrase, given Hooke’s pronounced curvature of the spine. At at any rate, they were both at least partially right: Physicists today appreciate the wave-particle duality of light.

Then there was the dispute perhaps alluded to in the portrait, about the elliptical orbits of the planets. Hooke claimed in 1684 that he could mathematically demonstrate what’s known as Kepler’s first law, which Newton published in his famous Principia Mathematica. The upshot was that Newton removed mention of Hooke’s important contributions from his book—and they never got along again.

Hooke died in 1703, the same year that Newton became president of the Royal Society. There is no record for Royal Society ownership of this Beale painting. All Newton had to do was leave it behind when the Society moved official residence in 1710, thereby ridding himself (and history) of hard evidence of Hooke’s claim.

Where the painting has been during the intervening centuries is a matter of conjecture. When it first came to light at a Christie’s auction in the 1960s, it was ironically labeled as a portrait of Isaac Newton. Sotheby’s, the last public auctioneer of the work in 2006, has not revealed the buyer’s identity. I hope the current owner comes forward and sells the portrait to the Royal Society. That’s where it belongs, at long last. I would love to see the original.

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

* Update 9/8/20: This article has been updated to clarify Hooke’s work on elliptical orbits.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook