Nashville’s Cheatin’ Heart: Why Country Music Has Been Obsessed With Adultery for the Last Century

Some troubadour left his broken heart. (Photo: Tim Parkinson/Flickr)

Country music and cheating go together like whiskey and water.

Flip on any radio station—classic country, pop-country, alt-country, “truck-driving country”—and mixed in with the love songs and the hoedown stomps and the patriotic ballads, you’re bound to hear some poor soul walking the floor over the loss of his woman. Or some desperate soul pleading a temptress not to take her man. Or some angry soul carefully applying “a Louisville slugger to both headlights of his pretty little souped-up four-wheel drive.”

Brian Mansfield quipped on country site The Boot, “nothing is certain but death, taxes and cheating songs,” and music journalist Colin Escott once wrote that infidelity is to country music “what the blues in B-flat is to jazz.” Don’t believe the hype? The numbers don’t lie—one study of a quarter-century of popular country songs found that “cheating situations” were among the most popular of all situations, and at least one nonplussed academic attempting to sort the genre has had to close out the cheating category “because a list of extramarital sex songs could expand almost indefinitely.”

What is it about this type of music that draws all these straying and strayed-upon hearts? How far back does this tradition go? And now that so much of country comes not from the hearts of working-class heros, but from the guts of the Nashville music machine, is it in danger of being snuffed out by more palatable tunes?

The Start of the Affair

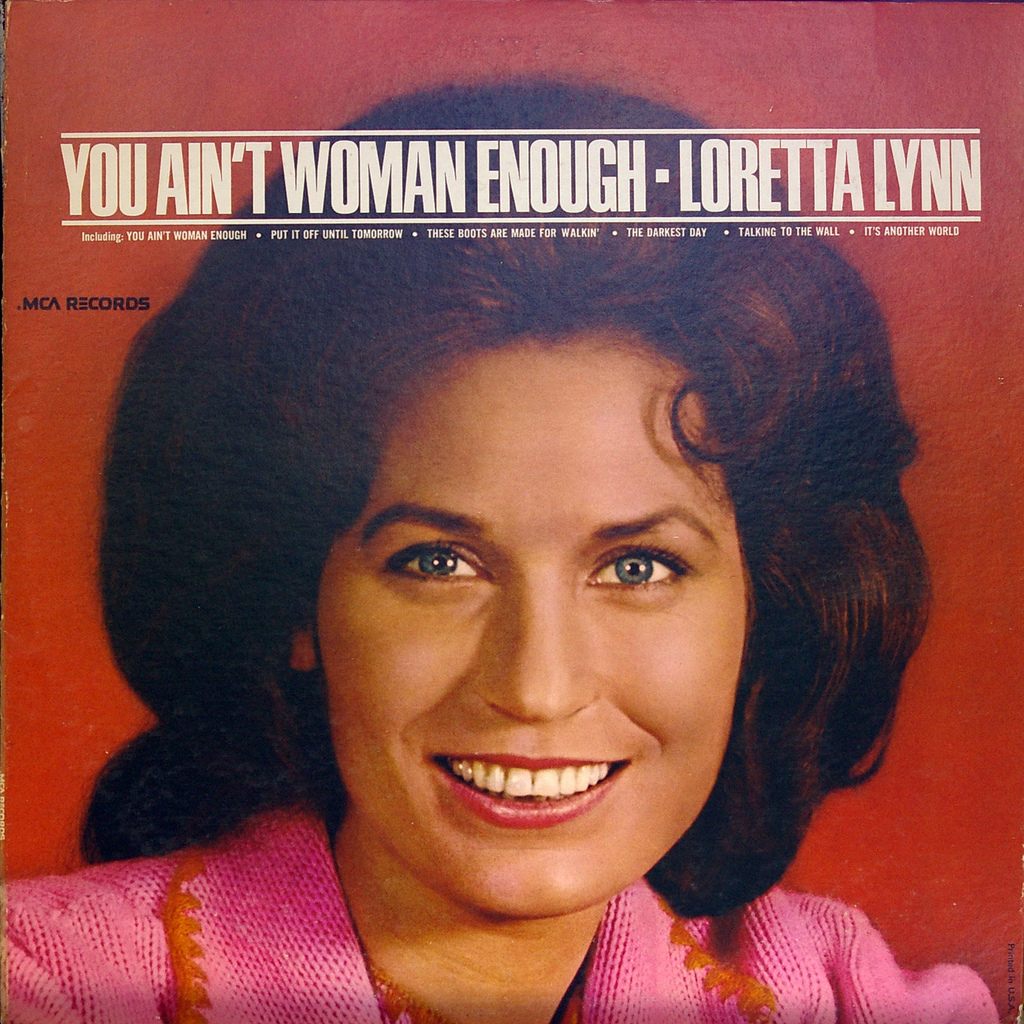

She’s said it before and she’ll say it again, about a million times throughout her career. Back off. (Photo: Nesster/Flickr)

Country has had cheatin’ on its mind since the genre’s inception. Although Appalachian bards had kept the songs of their European ancestors alive for centuries, strumming and picking on front porches from Texas to Tennessee, it wasn’t until the 1920s that anyone beyond the next street over took notice. The advent of portable recording technology allowed labels like Okeh and Victor to send scouts to Atlanta and Tennessee to find and record “hillbilly artists.” The Carter Family, Jimmie Rodgers, and other then-unknowns brought their favorite songs to the sessions, which were often held in strange places, like the Taylor-Christian Hat Factory.

Comb through any of these old recordings, and you’ll find plenty of cheatin’ strands. Many of the tunes were lifted, partially or wholesale, from old English ballads, which often dealt with faithless love. Take the 1927 Bristol Sessions, widely considered country music’s public debut: they include, sprinkled among the religious tunes and corn-shuck jigs, a surprising number of betrayals. The morbid “The Jealous Sweetheart,” by guitar duo the Johnson Brothers, tells the eerie tale of how said sweetheart stabs his girlfriend after he suspects her of cheating, while the last verse of “The Mountaineer’s Courtship,” by musical polymath Ernest Stoneman, reveals that the titular courtin’ mountaineer already has six children. Some warblers were all cheat: B.F. Shelton, a banjo player from Kentucky, recorded four songs that day, all of which end either with a nice girl leaving someone for a “low-down gamblin’ man,” or a ramblin’ boy killing his bride so he can screw around.

Why did these British folk songs—rather than the ones about Robin Hood and sea worms—resonate enough to survive so long? Country historian David Fillingim thinks it has something to do with the singers’ lot in life. Cheatin’ songs, like gospel songs or blues songs in other musical traditions, are “responses to the reality of suffering,” he writes—they’re a way to express that things are unfair, without mounting any sort of political critique.

The Carter Family’s best-loved song, and the first they ever recorded, was “Bury Me Under the Weeping Willow,” a deceivingly upbeat tune in which a betrayed woman hopes to die so that her philandering fiance will weep for her under the tree. (Photo: Victor Talking Machine Co/WikiCommons Public Domain)

Indeed, caring about cheating can be its own implicit socioeconomic statement. As one character, a singer, points out in Garrison Keillor’s WLT: A Radio Romance, “Cheatin’ songs. That’s real poor man music… A rich man hardly needs a woman at all…but when you’ve got nothing and not much to look forward to, then if your woman runs off and you lose the one good thing in your life, man, that just about kills you.” Such tales of woe “are in effect the redneck blues,” Fillingim theorizes, “the music of an oppressed people seeking to transcend but not ignore their experience.”

The early songs, particularly the murder ballads, had a moralizing bent, “encouraging listeners… to remain within the safe confines of Victorian sexual norms,” Fillingim continues. As the genre evolved and people began writing their own tunes, the theme remained, even as this subtext was dropped. Take “After the Ball,” the story of a man who abandons his sweetheart when he sees her kissing another ballgoer, and a 1930 hit for Fiddlin’ John Carson. The mysterious “suitor” turns out to be the sweetheart’s brother—meaning the true villain is the narrator, who, in his distrust, has cheated himself. “Many a heart is aching, if you could read them all,” Carson caterwauls sadly over his fiddle. “Many the hopes that have vanished after the ball.” “After the Ball” is suffused with regret, but it’s not a murder ballad; it has a twist ending, but it’s not a joke. It’s a cheatin’ song.

Whiskey and Stepping Out

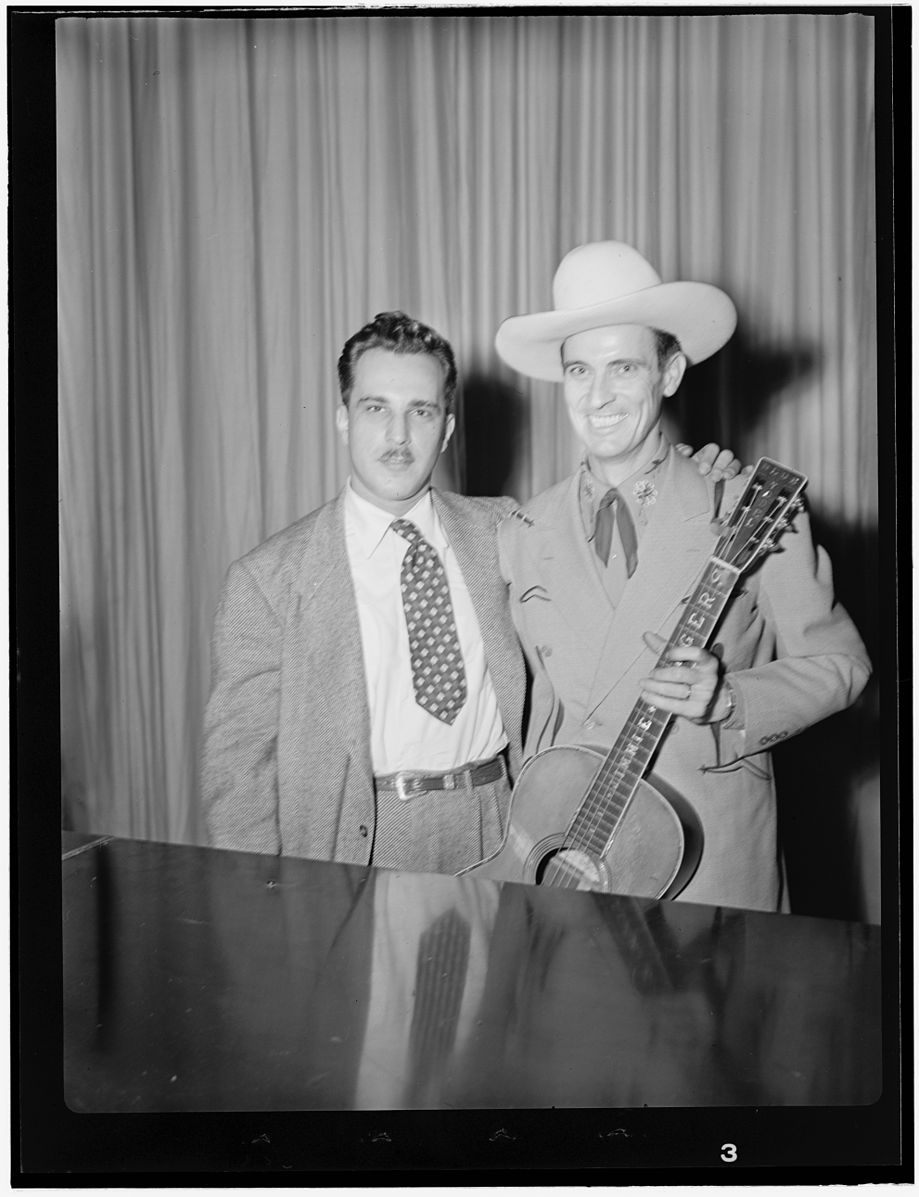

Ernest Tubb (right) with fellow musician Dave Miller. Tubb’s trademark laconic voice was the result of a tonsilectomy, which robbed him of the ability to yodel. Before that, he had basically been a wannabe Jimmie Rogers. (Photo: William P. Gottlieb/Library of Congress Public Domain)

After Prohibition was repealed in 1933, country music lost a bit of its innocence, swapping parable-ready ballrooms for rough and raucous dance halls. The honky-tonk era was a cheater’s paradise—everyone was drinking in the reopened dive bars, and rubbing up against strangers all over the increasingly urban and industrialized South. Honky-tonk’s devilish prince was Ernest Tubb, aka the Texas Troubadour, whose fluid picking and burred voice leant a certain jauntiness to his many tales of perfidy. Tubb’s biggest hit, “Walkin’ The Floor Over You,” is double-crossing you can dance to—the Troubadour sounds, at worst, mildly exasperated as he describes his can’t-sleep can’t-eat pacing-the-house symptoms, and ominously jokes that “someday you may be walking too/walking the floor is good for you.”

With “Walkin’ the Floor Over You,” Tubb tapped into another great cheatin’ song wellspring—wordplay. “Country, with its adherence to a limited number of themes, is forced into actually surprising lyrical cleverness and inventiveness,” says Charlie Hopper, a self-schooled countryphile who has been drafting songs for Nashville for years. In Figure It Out: The Linguistic Turn in Country Music, scholars Jimmie N. Rogers and Miller Williams point out country’s particular love of “syllepsis,” the act of using one word to mean two things—see Loretta Lynn’s “While He’s Makin’ Love, I’m Makin’ Believe,” Gene Watson’s “You’re Out There Doing What I’m Doing Without,” and Conway Twitty’s “Something Strange Got Into Her Last Night.”

Cheating stories, which bring along metaphor, euphemism, and comic or tragic punchlines, are particularly ripe for syllepsis—and in turn, syllepsis gives those punchlines their cornball appeal.

But cheating songs aren’t just bad puns and switcheroos. The next great bruised-heart king was Hank Williams, and he took his wounds seriously. Williams was one of the briefest-shooting, brightest-shining stars of country music, with 35 country top 10s in his 16-year career. Audiences loved him so much, the producers of the Grand Old Opry had to instate an encore cap for his performances. Most importantly for us, he was also the author, singer, and occasional embodiment of “Your Cheatin’ Heart,” the song that critic Colin Escott says “to all intents and purposes defines country music.”

“It was Hank’s career that made cheatin’ songs a way of life,” says Fillingim.

Hank’s Broken Heart

Williams’s late-career focus on faithlessness came from personal experience. By early 1952, an old back injury had started acting up, and his self-medication routine, which was largely alcohol- and morphine-based, quickly grew into its own problem. He was in and out of rehab, and on thin ice with friends, relatives, and audiences. Worst of all, his marriage was falling apart—his wife, Audrey Sheppard, had kicked him out of the house, and Williams feared his alcoholism had driven her into the arms of another (or several others).

In July 1952, Williams and Sheppard officially cut ties, and Williams started cutting some sad, sad songs (the batch recorded the day after the divorce was finalized “seem like pages torn from his diary,” Escott writes in Hank Williams: The Biography). A few weeks later, on the highway with his new flame, Billie Jean, Williams got to venting. “He said that someday, his ex-wife’s cheating heart would have to pay,” Don Tyler writes in Music of the Postwar Era. Immediately, Williams knew he was onto something—“so he composed the lyrics in a matter of minutes and had Billie Jean write them down” while he kept driving.

And so “Your Cheatin’ Heart” was born. Widely regarded as one of the best songs of all time, it became his second #1 hit, topping the charts for 6 weeks, and was the first country song ever inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame. Williams, who died a few months after the song was recorded, told his friend, “It’s the best heart song I ever wrote.”

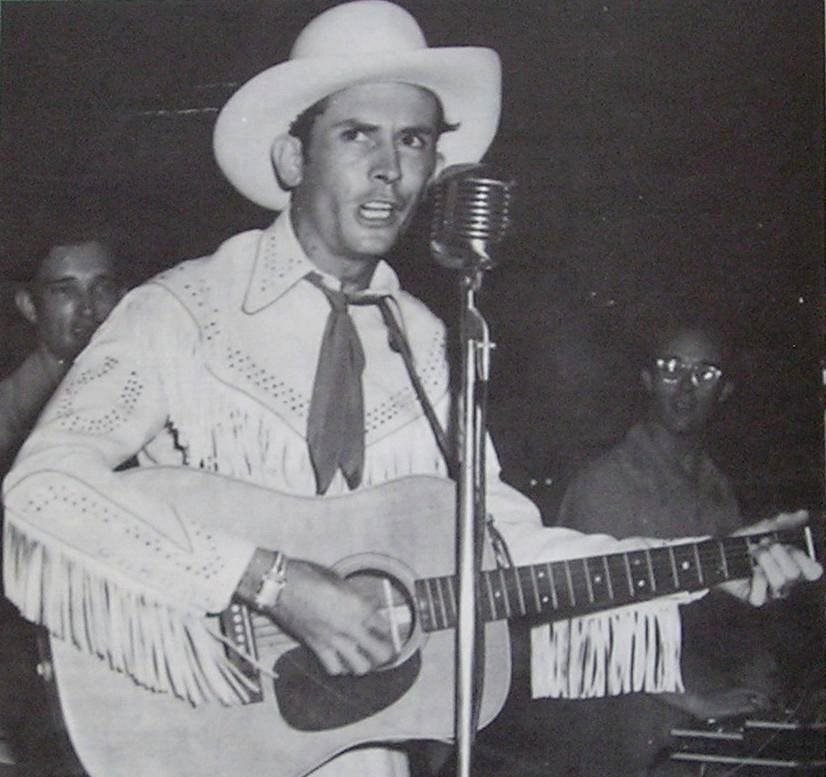

Hank Williams, all scowls and tassels, performs in 1951. (Photo: MGM Records/WikiCommons Public Domain)

It also shot yet another dose of new life into the cheatin’ song. Though the theme was already a cliché, Escott credits Williams’ “subtextual chisel and thirst for vengeance” with rejuvenating the form. For country, the American midcentury was an age of authenticity, and if you were a star, “you really seemed like you were pouring out your heart and you had lived this stuff,” says Hopper. “They were drinkin’ hard; they were suicidal; they were throwin’ themselves off bridges: they were willing to be pretty grim.” To the artists of this era—Williams, Loretta Lynn, Johnny Cash—penning song after song about cheating was just being honest.

The Anatomy of a Cheat

In 1973, Dolly Parton released “Jolene,” which catapulted up the charts and made the 27-year-old Parton an international star. Inspired not by some sort of marriage-ending siren, but by a red-headed bank teller who wouldn’t stop flirting with her husband, the song is not so much “authentic” as a well-observed collection of details convincingly grafted onto a theme. “It’s really an innocent song all around, but it sounds like a dreadful one,” Parton told NPR in 2008.

In the song, Parton pleads hurriedly for Jolene, with her “flaming locks of auburn hair,” to find some other man and leave hers alone. The song’s three minutes fly by in a rush of minor chords, keening violins, and quickened-heartbeat drums. In the years since its release, “Jolene” has cheated on Parton with dozens of artists from almost as many genres—there’s an electro-pop Jolene, a punk Jolene, and a cumbia Jolene, and as of three days ago, the song is even sleeping with network TV.

Cheating songs have a lot of moving parts. All of them have at least three characters, each of which can be the narrator or the person being addressed (if you’re singing a duet, you can even combo). On top of that, you have various relationship stages, emotional tenors, and consequences. “If you were to get out a piece of legal paper and write CHEATING at the top, you could write down all the different aspects of it and probably find a song for each combination,” Hopper says. Other Woman, sadly singing to cheating man pre-discovery? Check. Wannabe-cheater lustily singing to potential conquest? Check. Cheated-on man angrily singing to Other Man while filling his order at a McDonalds drive-thru? Checkeroo.

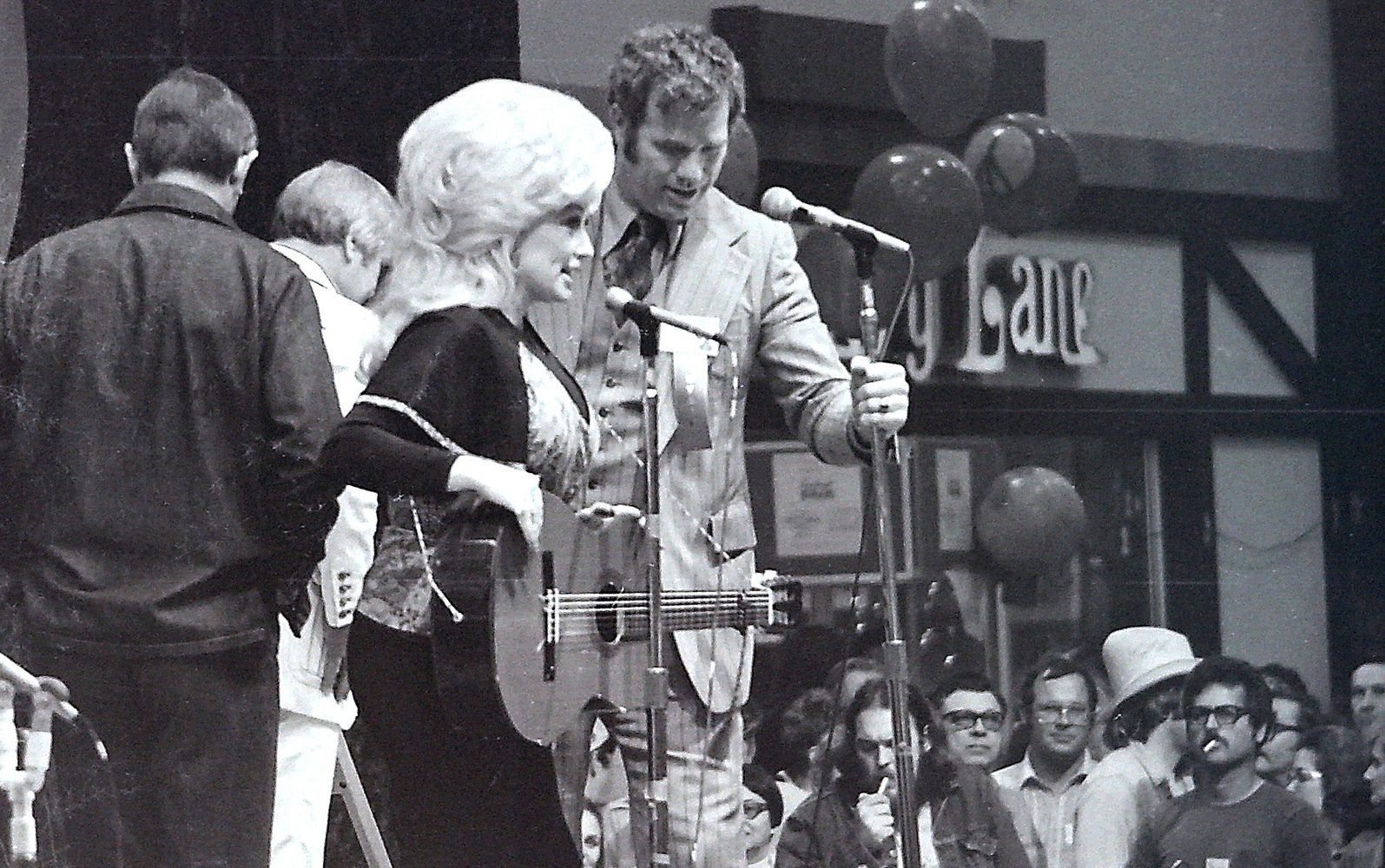

Dolly Parton onstage in 1977. (Photo: Jay Phagan/Flickr)

Those who cover, riff on, or parody “Jolene” tend to latch onto one of the many permutations made possible by its particularly complex structure, which folds itself into a few possible love triangles. Jack White imagines Jolene is his girlfriend, and that he’s begging her to lay off one of his friends. Parton herself toes the line between dignity and desperation, while Mindy Smith fully empowers the narrator and writes off Jolene as a “woman who steals stuff.” (In her cover, Miley Cyrus pretty much just keeps bein’ Miley.)

Country music has a somewhat limited palate, and adultery is one its primary colors. “To say something fresh and literal is the hardest thing,” Hopper say. But if you have a mess of variables to slot into your tried-and true story structure, it gets a little easier.

The End Of The Affair?

If you have professional songwriters, it’s easier still. Sometime in between the Dolly Parton era and today, country music became according to Hopper, “extra pop.” “All the people went to Nashville, and you had this real devotion to songcraft,” he says. “Before He Cheats,” from 2005, was sung by Carrie Underwood, but it was written by hitmakers Chris Tompkins and Josh Kear—an arrangement that might have itself been considered cheating in the more authentically-minded midcentury, but has since become the norm. In the song, Underwood details the many horrific things her partner is probably doing while at a bar with someone who is not her—and then, in a rousing chorus, the equally horrific things she, Carrie, is doing to his car in the bar parking lot.

Hopper says that “Before He Cheats” is a crackerjack country song, full of everything that makes the genre great—a clever structure; replay-ability; concrete details that trip off the tongue. But it also illustrates several ways in which the Nashville machine has placed new restrictions on the cheating song, which does not awaken ”a commercially viable emotion for moms in minivans, who are the kind of cliche but still accurate target,” Hopper says.

For one thing, it’s Underwood’s only one. “It’s like the artists are collectors, and they want to have a representative collection of songs,” Hopper explains. “Unless you’re gonna be the Andy Warhol guy, you just want one Warhol on your wall. If you’re [a country star], you probably do want a cheating song, but you don’t want a bunch of cheating songs.”

Carrie Underwood croons to Colorado Springs in 2006. (Photo: MrHairyKnuckles/Flickr)

For another, it fits into one of a narrowing list of acceptable perspectives. “Usually the women sing defiantly about being cheated on,” Hopper says. “They have to be careful to not make themselves look like bad people.” Men can barely sing about cheating at all anymore—“if they’ve been cheated on, they look weak, and if they’re the predator, they look unlikeable,” Hopper says.

“People say, ‘Oh, the therapist who is having the baby of the guy she was counseling for drinking, that sounds like a country song,’” Hopper says. “But it actually sounds like an old country song.” After a century of hanging around willow trees, honky-tonks, tear-stained floors, and bank lobbies, Nashville just isn’t as willing to go there anymore.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook