The Brief, Baffling Life of an Accidental New York Neighborhood

Welcome to Haberman, Queens, population: zero.

Maps are reflections of our world—how it is organized, how we experience it—or at least that’s what they’re supposed to be. At their best, maps help you understand the space around you, but at their worst, they can warp reality, by stripping communities of their power or rights, for example. And you thought bad directions were the worst that could happen.

Maps are contentious in part because land is so often tied to identity. Urban neighborhoods, as one of the more nebulous and amorphous spaces for cartography, often make for interesting, if low-stakes, confusion. And when the desire to name and label everything runs into data and algorithms, strange things can happen.

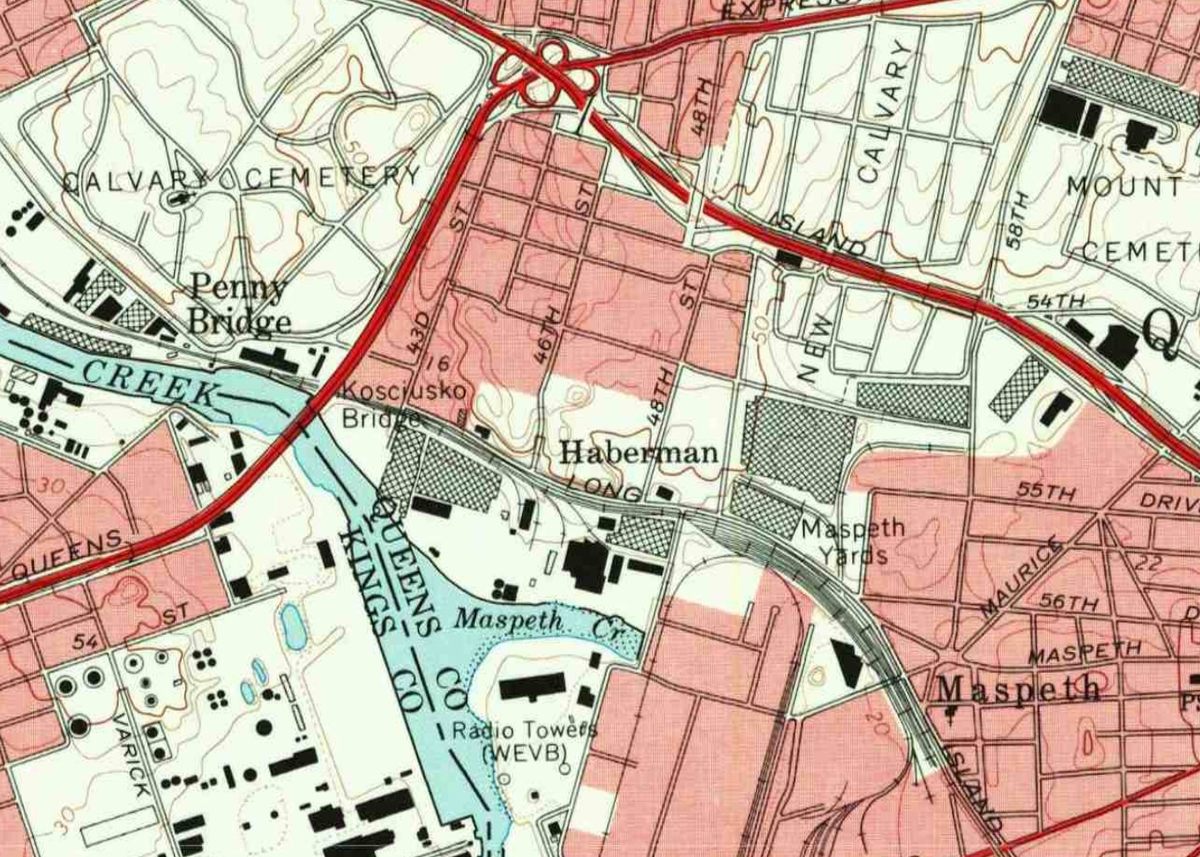

In summer 2018, Jeff Sisson, a 31-year-old software engineer, was a new arrival to Queens, the largest borough in New York City by some 40 square miles. Sisson was getting to know his new environs by foot and bike, and one day while surfing Google Maps, he noticed something strange. He saw a designation on the map for something he had never heard of before, a place called Haberman.

“After having to route myself into some areas that are near that particular place in Queens, it just sort of stood out to me,” he says. “The size of it was large enough that implied something very real, present, and visible, but it was not totally clear what it referred to.”

The name was prominently displayed on the map, denoting a locale in western Queens. So Sisson decided to do some detective work. Was it the newest neighborhood rebranding effort by real estate moguls? Or the revival of an old, long-forgotten locality? A technologist by trade, Sisson started looking for answers via the same company that raised the question: He googled “Haberman.”

“I was just looking for things that are available to mere mortals,” Sisson says, “that might point to some origin about why this was on there.”

His search turned up a surprising (or unsurprising) number of local businesses that appeared to offer services to residents of Haberman: a dentist, a pressure washing company, bed bug exterminators. The businesses appeared to be legitimate, but Sisson thought the online presence a little fishy. The sites all seemed to be programmatically generated, with similarly awkward phrasing on each one, such as saying “in Haberman - Queens, NY” over and over again, probably to trick search engines into driving any kind of neighborhood-focused search traffic their way. “They were all a certain kind of website, one that’s sourced from piece of data that’s freely available,” he says. “It pointed at some not-exclusive-to-Google source for the data.”

So Sisson dug deeper. Where were all these websites pulling their information from? Between the uncanny business listings, Sisson found a brief Wikipedia entry for a long-defunct operation.

In September 1892, the Haberman Manufacturing Company in Maspeth, Queens, got a rail station to service its workers commuting from Long Island and elsewhere. The company specialized in enameling ironware—a pretty significant industry at the time, apparently. In 1893, the Haberman company even had a case heard before the Supreme Court. (It lost.) Though the company closed in 1920, the Haberman train station remained, at least until 1998, when the stop on what has come to be known as the Long Island Rail Road was permanently closed due to low ridership. (The previous year, Haberman averaged three riders per day.)

But how did this defunct train station end up looking like a neighborhood on Google Maps? Sisson got lucky in his search—one site specified a Geographic Names Information System (GNIS) number for Haberman, part of a system used by the U.S. Geological Survey. The USGS maps had spaced neighborhood and train station names differently so they could be distinguished from one another, but somewhere along the line there had been some confusion, and Haberman was clearly listed as a populated place. Sisson speculates that a USGS employee made the simple mistake when the old maps were being digitized, and then those data got a second life then they were picked up by Google Maps’ algorithms.

On the most widely used maps—those made and distributed by tech companies such as Google, Apple, and Yelp—infinite amounts of information can be displayed. All you have to do is zoom in. So they’re data-hungry. Matt Zook, a geographer at the University of Kentucky, says that “Google is sort of promiscuous about data. It’ll pull it wherever it can find it.” But when it can, the company prefers reputable sources, such as the USGS.

The site of the former Haberman station is an industrial area populated mainly by extrajudicial NYPD parking spots and some package pickup depots. But it is still in the middle of a densely populated city. Sterling Quinn, a geographer at Central Washington University, is primarily focused on the American West, but his work provides some insight into the curious case of Haberman. Out there, in an industrializing United States, train stations had become vital landmarks in sparsely populated areas. Today, many depots’ names remain prominent in Google Maps.

“In New York City, [Haberman] is kind of hidden among a bunch of other stuff. Let’s say you apply an algorithm that works out West, maybe it doesn’t work in this urban context,” he says. He points to the Hutterites, an ethnoreligious group that has a commune in rural Washington, west of Spokane, among many others. The Hutterites live in relative isolation, but as a populated place, their community has a GNIS number. In turn, the Hutterite communities, with a variety of names, stick out like a bunch of sore thumbs on Google Maps.

“It’s ironic,” Quinn says, “because I think one goal was for them to get as off-the-map as possible.”

In a city, on the other hand, historical names that have long fallen out of use drift through and surface in the data in a whole new way—less as waypoints and more as artifacts of automation.

“Maps don’t only represent places, but they have the potential to create them,” says Quinn, who specializes in OpenStreetMap, an open-source, user-generated platform, and has recently spent time looking at disputes over names and borders that arise in online maps. “There is potential for maps to create, or at least exercise, an influence on the landscape,” he adds.

The Haberman case is relatively innocuous, but in 2008, concerns arose in Buffalo’s historically black Fruit Belt neighborhood when Google Maps algorithms labeled the area “Medical Park,” a nod to the rapidly growing medical center nearby. The misnomer was replicated across dozens of websites, a geographic error that had the effect of wiping a neighborhood and its history off the map. (Google revised their map in February 2018, a decade later.)

“What it basically comes down to is that people don’t like blank spots on a map,” Zook says. “You think back to Age of Exploration maps, the reason they put the little sea dragons and the ‘Here be monsters’ on the map is because they didn’t know what was there.”

Zook believes that there’s a “similar kind of thing” happening with Haberman. “This area was industrial,” he says. “There wasn’t a neighborhood feel to it. Since it really didn’t have an identity, I can imagine someone just saying here’s a name on this map, let’s add it.”

Haberman was a glitch, a mistake carried over, a relic, a product of the cartographic desire to display as much of the world as possible. Though, in strange twist, it may return. In 2018, a New York City Department of Transportation study actually recommended reviving Haberman station, among others.

Shortly after Sisson published his analysis on his research blog, Haberman disappeared from Google Maps. Though it’s possible that the algorithm corrected itself, the timing strikes Sisson as suspicious. And even if the peculiar case of Haberman is never fully settled, Sisson is sanguine.

“The thing I really wanted was a Google engineer to reach out to me,” he says. “I’m sure there’s an NDA reason that wouldn’t happen in a million years, but I hope that one day, in some bar, some guy will lean over and tell me ‘Hey, I deleted Haberman.’”*

* Update, October 16, 2019: After reading this story, a Google employee contacted Sisson to confirm that the company did indeed delete Haberman from Google Maps—an action prompted by Sisson’s original blog post.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook