Octopuses (and Their DNA) Suggest Antarctica Will Melt Again

Two geographically separate populations of cute cephalopods once mated a very long time ago.

Did the West Antarctic Ice Sheet completely collapse during the latest interglacial period, about 125,000 years ago? It’s an important question for climate scientists, but geology was giving them no answers. So they turned to genetics instead.

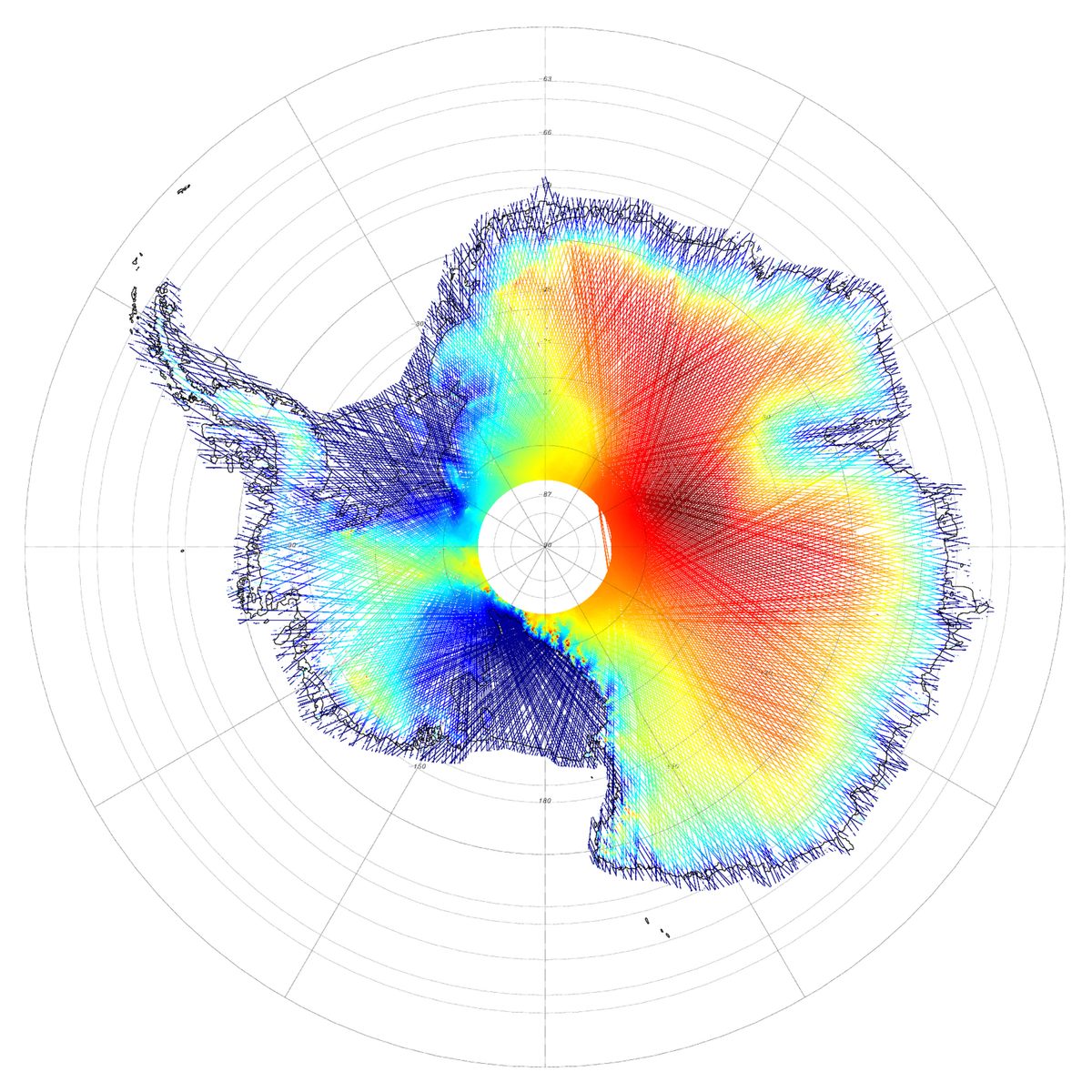

Enter Turquet’s octopus (Pareledone turqueti), a cephalopod with a four-million-year pedigree that makes its home in the icy waters around Antarctica. Recent DNA analysis shows that two distinct populations of this species, one in the Weddell Sea and the other in the Ross Sea, mated about 125,000 years ago.

This could only have happened if the massive ice sheet that now separates those populations wasn’t there at the time. So yes, it did collapse. And that’s bad news, because it increases the likelihood that it will happen again.

The Importance of Antarctic Ice

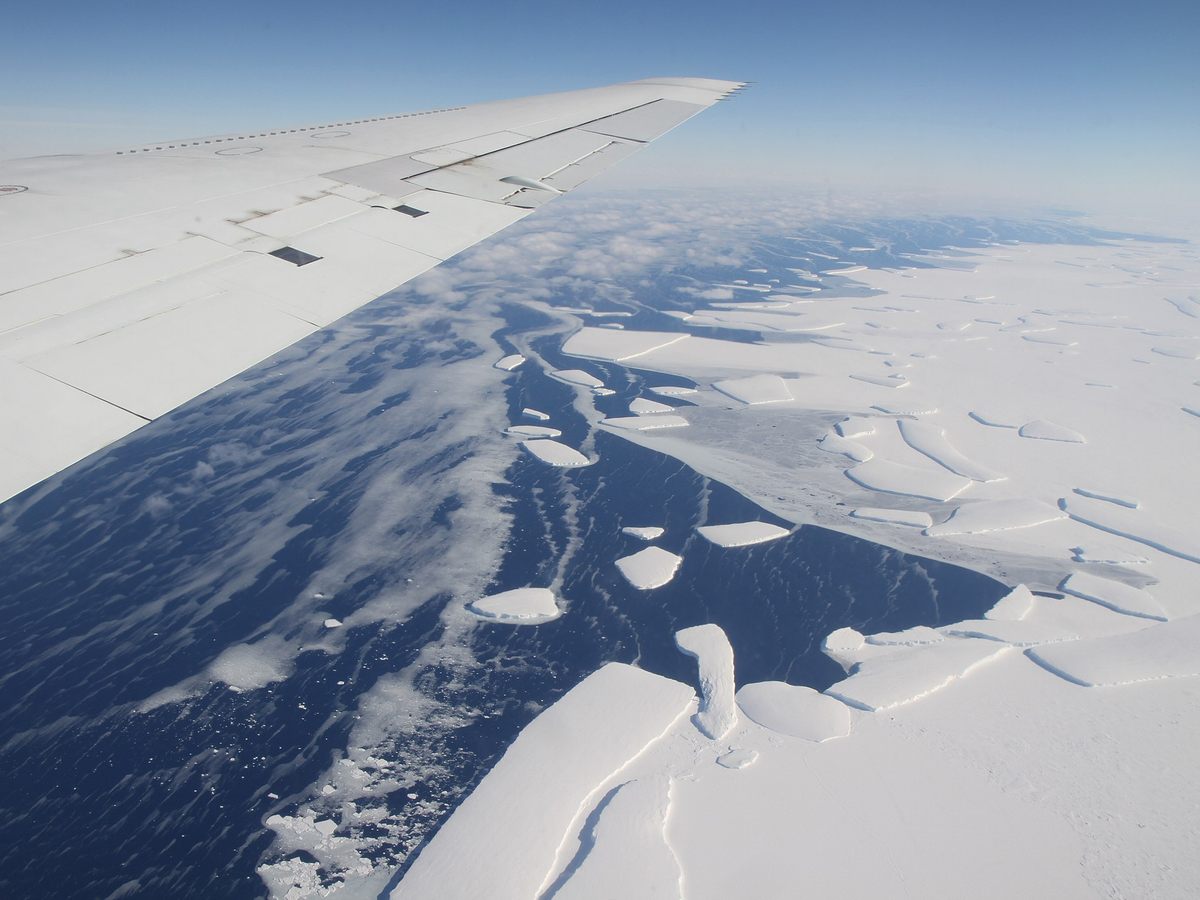

While ice is melting at both poles, the situation in the Antarctic is much more dramatic. The North Pole is just a relatively thin layer of frozen water that expands and contracts with the seasons—its volume ranging from a few hundred thousand to a few million cubic kilometers (several hundred thousand cubic miles). Scientists predict the Arctic could be entirely ice-free in summer by 2035 and year-round by 2050. At that point, there will just be open ocean at the top of the world.

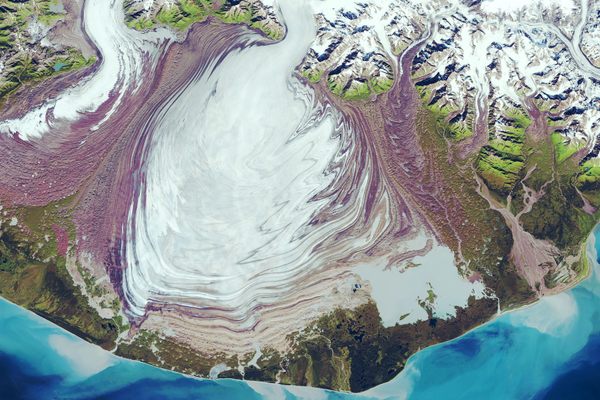

The South Pole, in contrast, has a solid foundation, upon which rests a thick ice layer up to several kilometers (a couple of miles) deep. In all, Antarctica holds 26.5 million cubic kilometers (6.4 million cubic miles) of ice, which represents about 90 percent of the world’s total ice volume.

That abundance of ice obstructs our view of the continent beneath, which is much smaller than what currently appears on our maps—a vast white blob with a small tail. Should the South Pole ever un-freeze entirely, East Antarctica would retain its solidity, but West Antarctica would fragment into an archipelago of a few large and very many smaller islands. The Antarctic Peninsula (that tail) would turn into a free-floating island.

Octopus Tales

As scientists have now established (in a study released as a preprint on bioRxiv), this is indeed what happened during the last interglacial period, when temperatures were similar to today. They collected genetic evidence indicating that two distinct populations of Turquet’s octopus mixed their DNA, which could only have happened via a waterway between the Weddell and Ross Seas, now sealed off by the West Antarctic Ice Sheet.

The question is for how much longer that sheet will stick around. The rate of ice loss across Antarctica is increasing. And the circumstances now are very similar to those during the last interglacial period, when temperatures were between 0.5° C and 1.5° C warmer than just before the Industrial Revolution. The Paris Agreement aims to limit global heating to 1.5° C above that pre-industrial level. However, this research suggests that even if we hit that target, the West Antarctic ice sheet still could collapse.

In the last interglacial, sea levels were 5 to 10 meters (16 to 33 feet) higher than today. The melting of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet would have been a major contributor to that rise.

Should it happen again, that will be bad news for the almost 750 million humans who live on small islands and in low-lying coastal areas around the world. But at least it will be a welcome change for Turquet’s octopuses looking for love.

This article originally appeared on Big Think, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time. Sign up for Big Think’s newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook