Stumbling on Skeletons in Old Odd Fellows Lodges

The fraternal organization has literal skeletons in their closets—and cupboards, back rooms, and attics.

In August of 2011, 16-year-old Jenny Minten was cleaning out a cabinet in the Independent Order of Odd Fellows lodge in Scio, Oregon, when she came across something unexpected: a child-sized coffin, caked with mud. When she pried it open, the surprises continued. Inside were a number of moldy, decidedly adult human bones: femurs, teeth, a mandible. Jenny called over her mother, Lindy, who in turn called 9-1-1. “I have a skeleton in the closet,” Lindy said, when someone picked up. (“We all do,” the dispatcher reportedly replied.)

A detective came by and picked up the coffin and its inhabitant. After an investigation by the sheriff’s department, which found no foul play involved, the remains were donated to the Oregon State University Osteology Laboratory, where Dawn Marie Alapisco, then an undergraduate student, began piecing them together.

The skeleton “pretty much just fell in my lap,” says Alapisco, now the university’s NAGPRA coordinator and a human osteologist. This tends to happen with skeletons and Odd Fellows lodges. Throughout the past few decades and across the country, people using, exploring, and renovating these buildings have opened a drawer or pulled up some false floorboards and been faced with a set of human bones.

The Independent Order of Odd Fellows, or IOOF, is a fraternal organization. It’s focused, in its own words, on “mutual aid and conviviality… [and] social and practical support.” Although it gets lumped in with so-called “secret societies,” current members balk at that designation. “Maybe we used to have secrets,” says Nancy Chew, the longtime office manager for the Odd Fellows lodge in Corsicana, Texas. “But these days we definitely do not.”

What they do have is the sort of general muddying that comes with long histories. For instance, people disagree about exactly how the IOOF got its name: the group’s official website says that in 17th-century England, when its parent organization was founded, “it was odd to find people organized for the purpose of giving aid to those in need.”

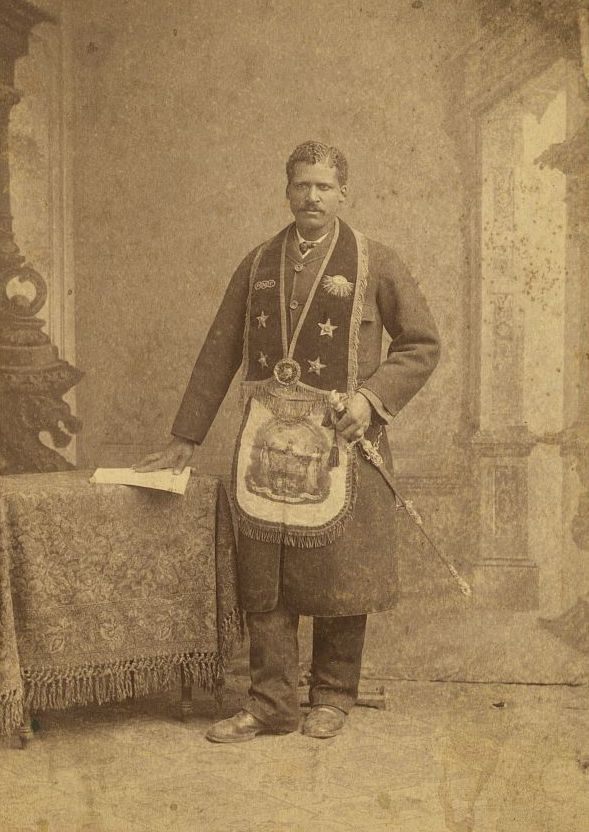

Others, including former group historian Charles H. Brooks, hold that it had more to do with the Fellows’ diverse membership, which—unlike the more status-conscious Freemasons—consisted of “men of every rank and station in life.” Either way, the group was popular: at its peak in the early 20th century, there were 3.4 million Odd Fellows in the United States, each committed to the Order’s main principles of “Friendship, Love and Truth.”

Like other fraternal organizations, the Odd Fellows use certain rites, rituals, and codes, passed down through the years and meant to facilitate the group’s shared values. One of these is a new member ceremony that includes, at some point, an encounter with a skeleton. “There’s really nothing too creepy about it,” explains Chew. “The lodge members are acting out a drama… [and] the skeleton merely represents the mortality of mankind.”

Other members have said that the ritual is meant to instill a visceral awareness of one’s own mortality. By literally looking death in the face, one is encouraged to live a virtuous life. (An anonymous account of one such ceremony—which made quite a splash when it was published in 1846, and may or may not be legitimate—describes how an initiate must confront a skeleton “kept rattling by means of wires,” while current members tell him “What thou art he was. What he is thou wilt surely be.”)

For this reason, Odd Fellows lodges generally keep a skeleton or two on hand. These days, they’re props, made of plaster or papier-mâché. In the past, though, it wasn’t difficult—or particularly unusual—to get ahold of a real specimen. (The one Alapisco studied likely came from De Moulin Bros & Co., an Illinois company that once offered an extensive selection of fraternal hazing standbys: robes and ribbons, trick chairs and fake goats, and “genuine, deodorized” skeletons, priced between $110 and $200.)

Said skeletons then linger in IOOF lodges, sometimes for decades, before surprising a new generation of Odd Fellows. Lindy Minten belonged to an associated organization, the Rebekahs, when she found the skeleton in Oregon. Other members have sold or given away old prop coffins without realizing—or at least without mentioning—that there were actual bones inside.

As membership dwindles, and the group’s buildings and belongings are repurposed for other community activities, non-members end up coming across the skeletons, too. In 2000, a theatrical collector in Missouri salvaged coffins from a disbanding Odd Fellows lodge, and discovered a skeleton in each: one fake, and one decidedly real.

The next year, an electrician fixing up a former lodge in Warrenton, Virginia, found one hidden in a recess in between two walls. “You could see the rib cage and the sinew,” he told the Washington Post at the time. “It was like a Dracula movie.” In 2004, a group of girls in Houston, Texas, stumbled on a casket full of bones during cheerleading practice. There have been similar finds all across the country: in a basement in New Jersey; a crawlspace in Pennsylvania; a cobwebbed wardrobe in Washington State.

Family discovers an Odd Fellows coffin and human skeleton in their barn: http://t.co/nsQWFKF4VL pic.twitter.com/3cjHrxRv38

— Sarah Chavez (@sarah_calavera) February 6, 2015

Once it is found, an Odd Fellows skeleton might come to any number of fates. One, called “George”—once an Odd Fellow himself, who donated his own remains—is currently on display at a former Odd Fellows complex in Liberty, Missouri. Some are auctioned off for charity, donated to medical schools, or sold online.

Others are given proper funerals by community members. “Jane Doe,” found in Pittsburgh, had a particularly eventful afterlife: after her tenure as an Odd Fellows skeleton, she was sold to a prop dealer, cameoed in Dawn of the Dead, and then ended up in a window display at a costume shop. She was finally buried in a local cemetery in 1983, after a policeman noticed that she looked a little too realistic.

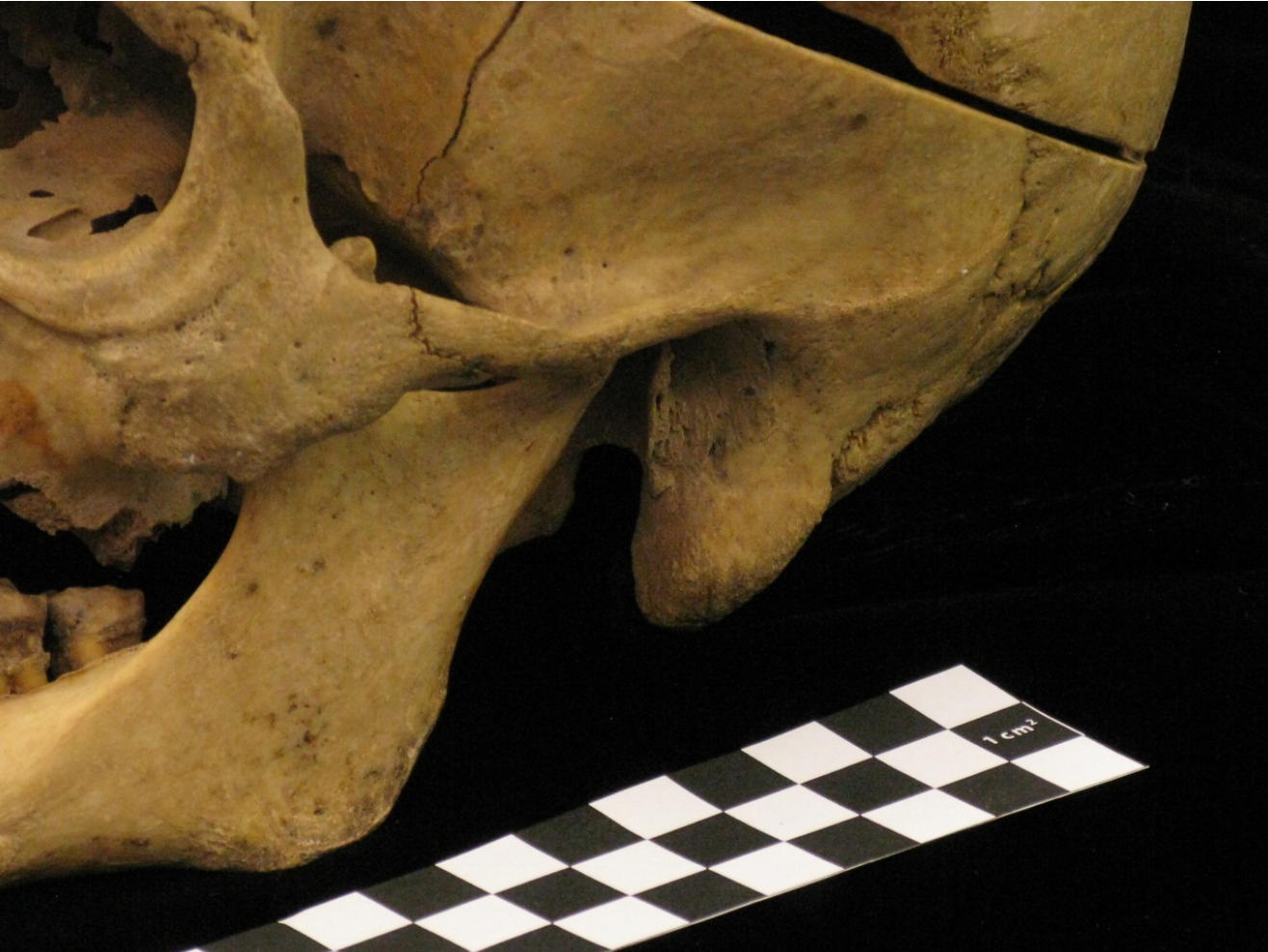

If they’re kept hidden, though, their prospects are generally bleak. The skeleton Alapisco studied had stayed in his child-sized coffin for about a century and a half. In 1962, when his lodge was destroyed by a flood, the coffin was removed, stored elsewhere for a while, and then put back in the replacement lodge, all without being cleaned. By the time he arrived at the university, he was completely covered in mud and mold. “He was so dirty,” says Alapisco, that when she and other students were cleaning him, “we had to wear masks, gloves, and ER-style robes.”

No one likes to find dirty skeletons in their closets. The Odd Fellows—who, according to their website, maintain a presence in every U.S. state except Alaska, as well as nine European countries and seven Canadian provinces—would rather the focus stayed on their charitable work, says Alapisco: “They don’t like it when there’s a big public thing [about the skeletons].” One member told me that certain chapters have begun using urns for the initiations instead, and others have made a point of getting out ahead of the problem, auctioning skeletons and other props before or soon after a defunct lodge changes hands.

The Scio skeleton has found a new home at Oregon State. Although Alapisco usually doesn’t name specimens—doing so is too close to “stripping the identity of who they were,” she says—she spent so much time with this one, she couldn’t resist, and she calls him Amadeus. After three lifespans spent in a pile in a box, he now often travels with Alapisco to talks, where she tells people about him—what she learned about his life, and all that happened after. “It’s all part of the story,” she says.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook