Mapping Old Rail Routes Like Contemporary Subways

They’re dreamy.

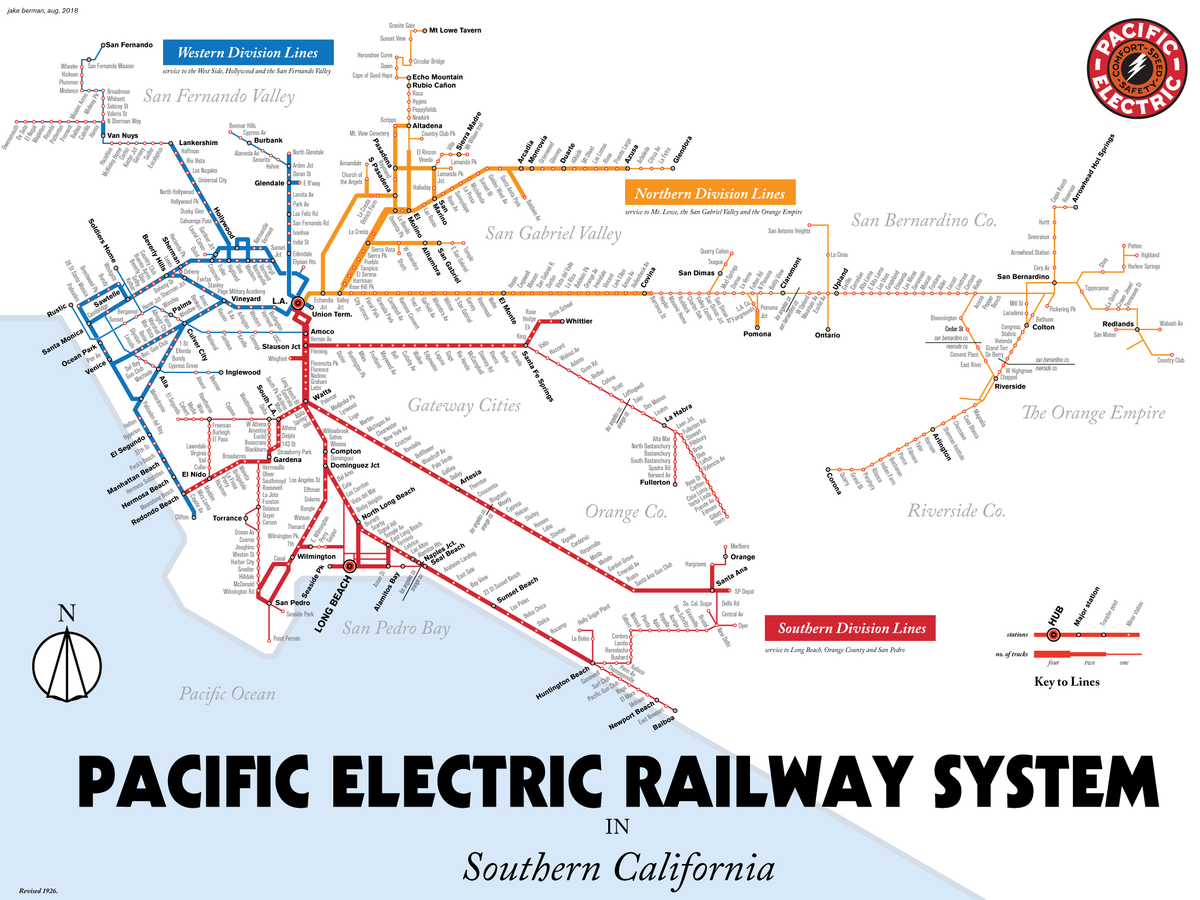

In 1905, if Angelenos were hot, bored, or stricken with wanderlust, they might make their way to the intersection of 6th and Main Street and climb on a trolley bound for the mountains or the waves.

These lines—pleasure routes operated by the Pacific Electric Railway Company—“reach from the mountains to the sea, and penetrate the valleys that lie between,” a promotional pamphlet proclaimed. Along the way, they made pit stops near all sorts of “points of scenic and romantic interest.” The “Mountain Route,” partway to Rubio Canyon, paused at an ostrich farm, where visitors could admire the long-necked birds behind a fence. When the car stopped beside a riotous field of poppies, riders hurried to gather them into bouquets. The “surf route” offered numerous chances to wade or plunge into the froth at Huntington Beach (named for developer Henry Edwards Huntington, who also owned the railway itself), or stroll above the waves beating against the newly constructed pier at Long Beach. Passengers were deposited at Alamitos Bay to feast on fish hauled fresh from the water.

The rail company operated many routes, including these ones that were pleasant, peaceful, and downright pastoral—nothing at all like the adjectives that would have crawled through Jake Berman’s mind, more than a century later, when he was stuck in gridlock on the notoriously sluggish U.S. Route 101.

To escape the frustration, Berman, an artist, let his mind wander. He got to thinking: Surely there must have been a different way to get around. He pursued the question at the Los Angeles Public Library. “Before long, I was deep down a rabbit role,” he says, “learning about the old Pacific Electric Railway.”

The system—once the largest electric railway in the world—boasted streetcars, freight trains, and more traveling along than 1,100 miles of track. It fizzled among growing freeways as well as its own maintenance woes and reliability issues, and was dismantled in the decades after World War II. Los Angeles now has a newer, smaller Metro system, and some of the lines run along the old rights of way, Curbed Los Angeles reported; some bus routes follow old corridors, too.

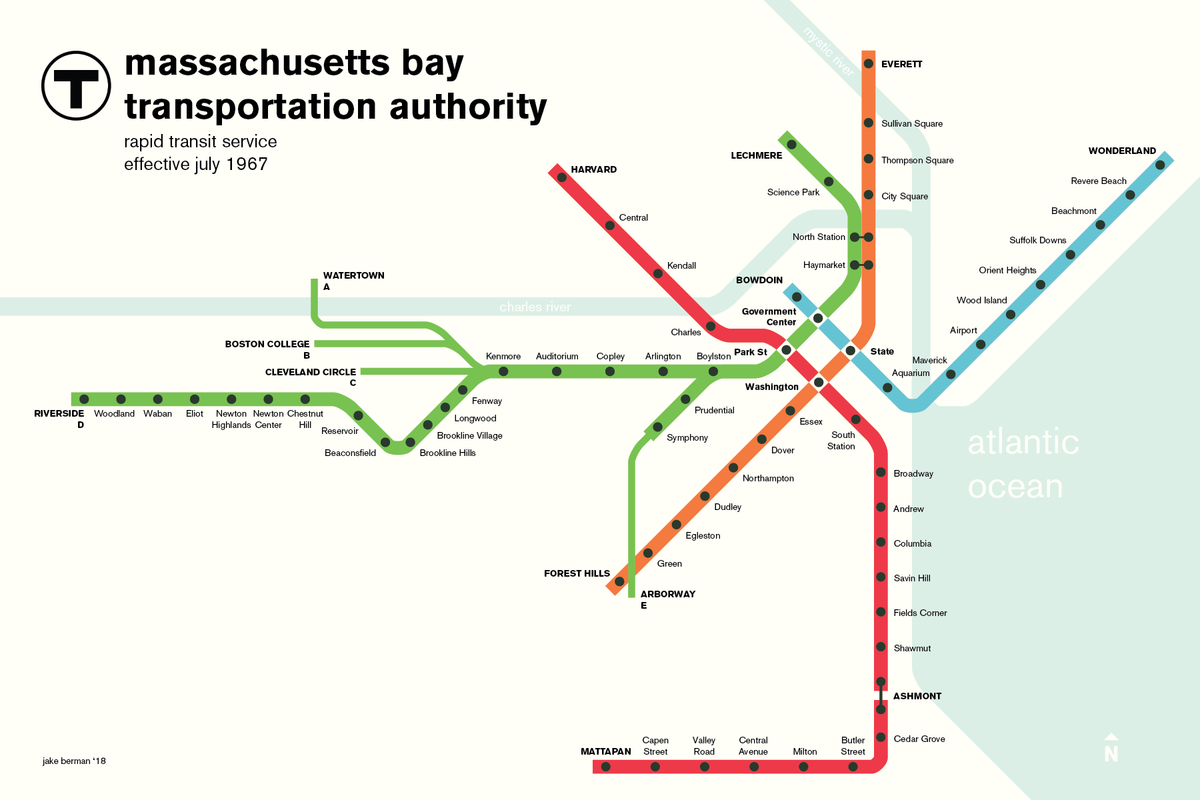

The legacy of the Pacific Electric and its red cars also lives on in a series of prints that Berman has made, portraying long-gone railway routes in the style of more contemporary mass-transit maps.

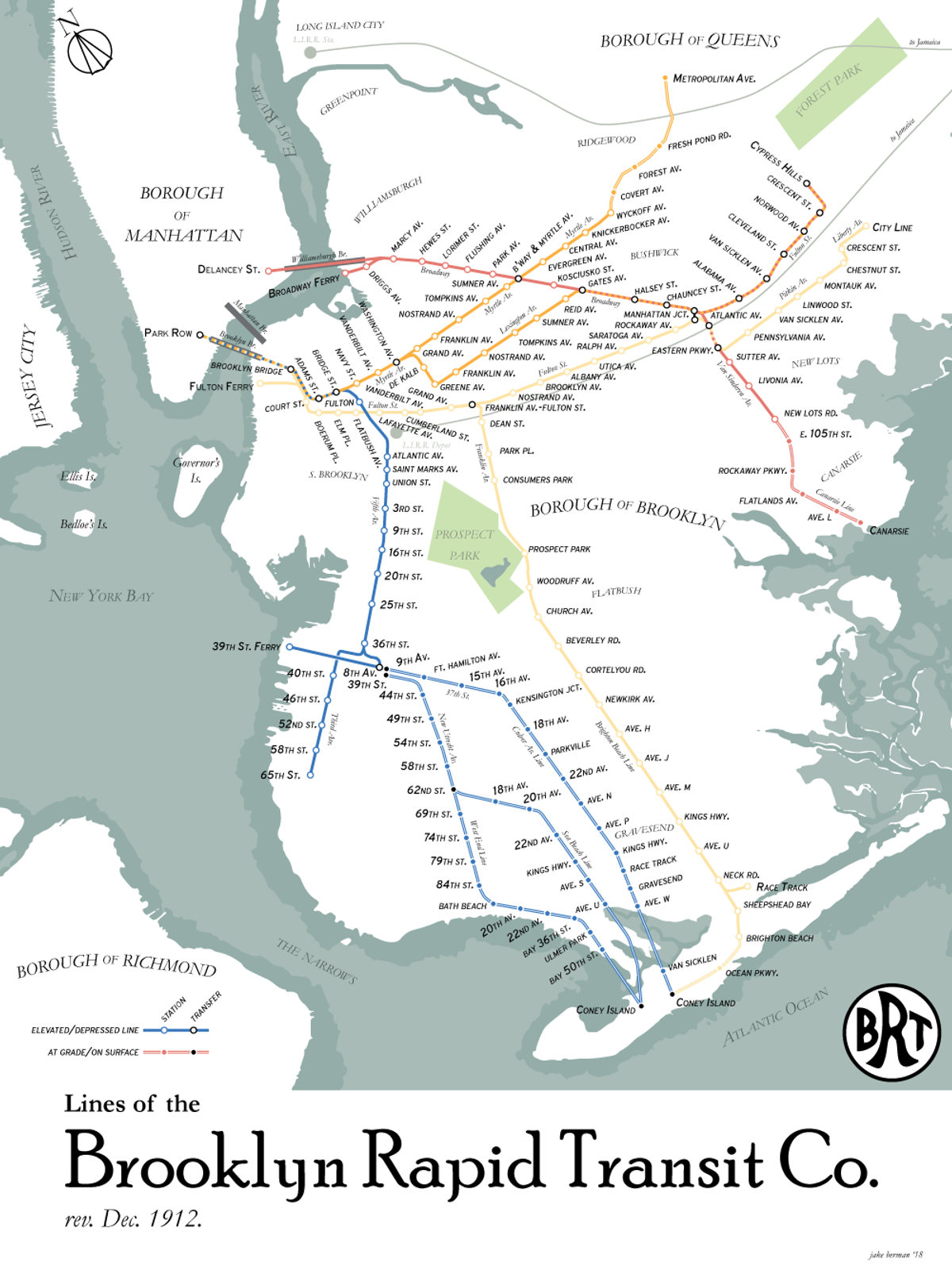

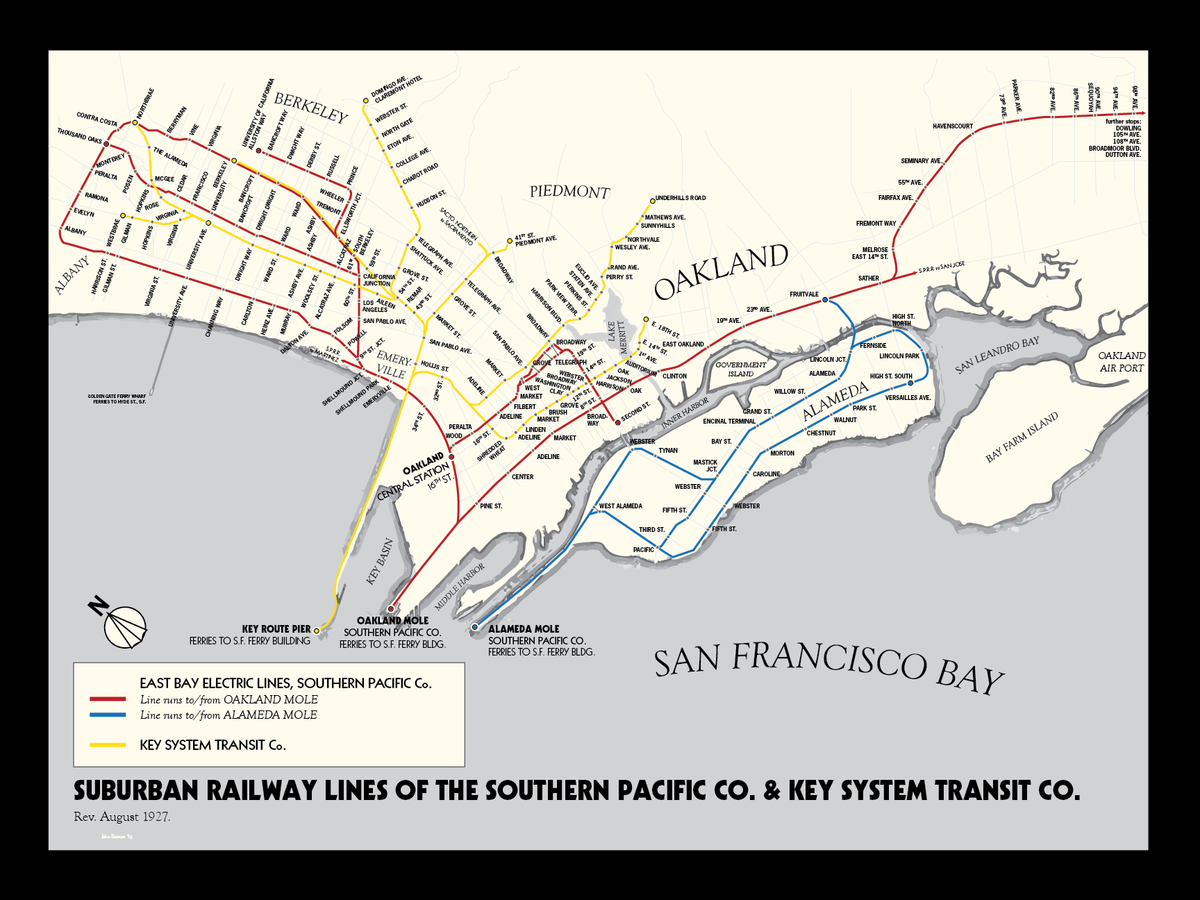

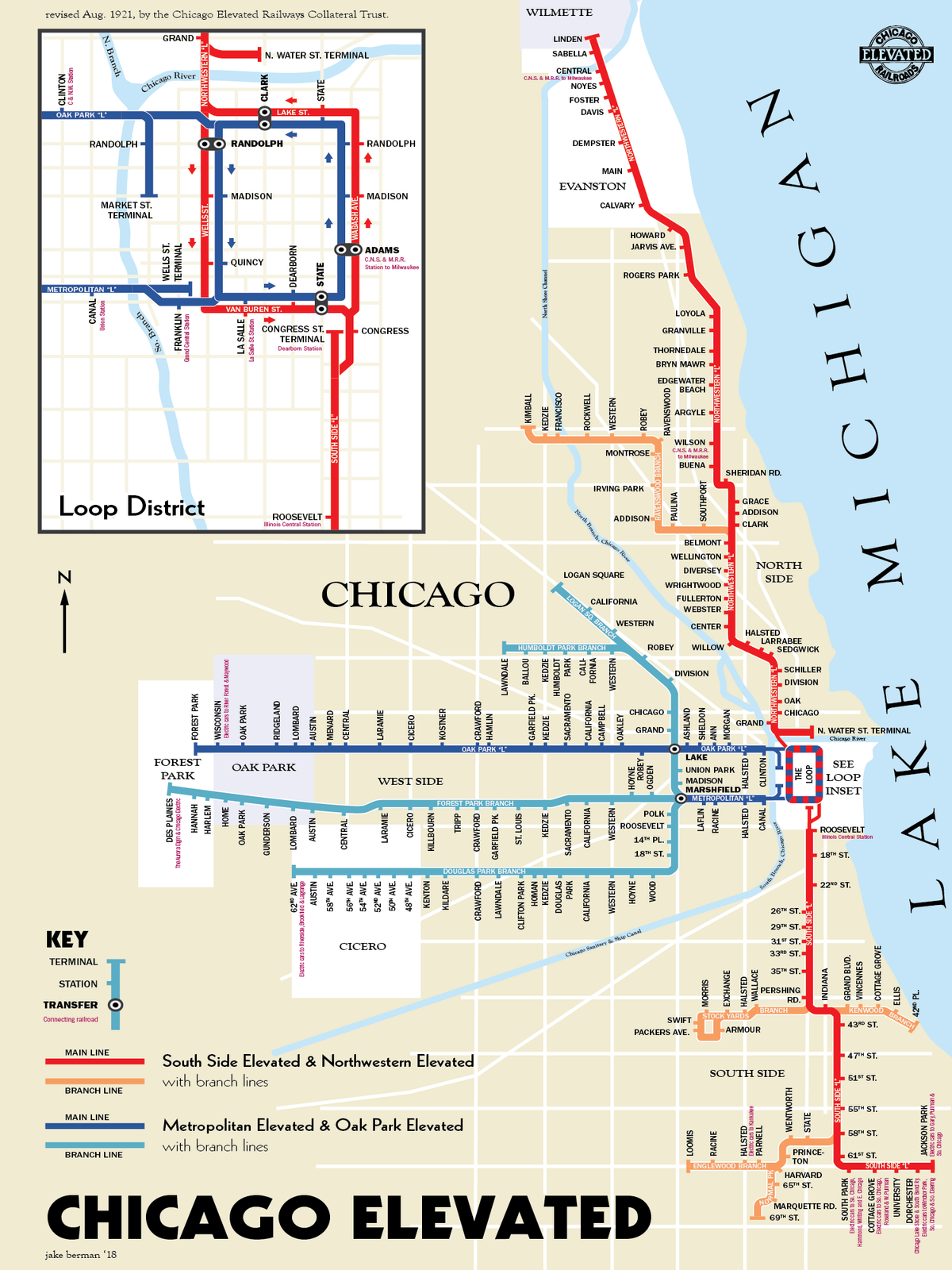

Berman trawls through old service guides and other primary sources to figure out where the routes led, then plots them out. All the while, he tries to balance legibility with a dash of period-specific styling—though his creations tend to be more colorful than their vintage counterparts. He’s worked his way through San Francisco and Los Angeles, plus Boston and New York. On the East Coast, some old stations endured as lines opened and closed: A predecessor of the present-day Broadway Junction station was born in 1885, for instance, when it was called Manhattan Junction. (Later, construction would replace and consolidate other stations on the same spot.) “I’m not trying to recreate period maps directly,” Berman says. “I’m trying to give the reader in 2019 a sense of what things were like in the past, with a relatable aesthetic.”

Hop aboard a sampling of Berman’s maps below.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook